Полная версия:

Gulls

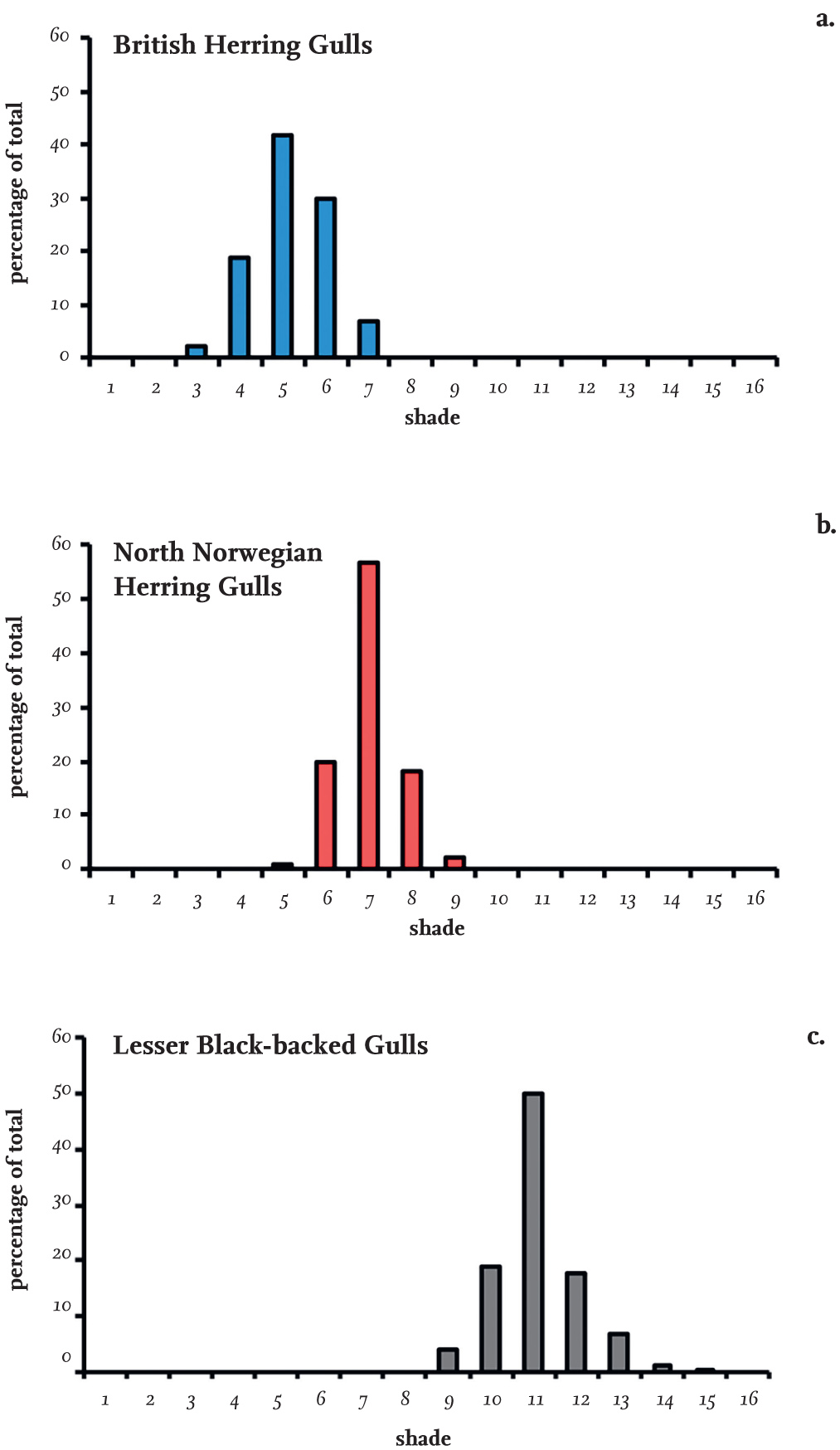

Identification of the Lesser Black-backed Gull subspecies intermedius and graellsii in the field is further complicated by whether the individual is seen in bright sunlight or under dull conditions, and also by the direction of the light, all of which affect the apparent shade of grey of the same individual recorded in photographs or observed in the field. Reliable records of shade need to be measured with the bird in the hand, using standard lighting and comparing it against a reliable shade chart, but even this would not identify the subspecies of all individuals.

FIG 7. The shade of the wings of adult (a) Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) breeding in Britain (n = 1,591) and (b) northern Norway (n = 140), and (c) Lesser Black-backed Gulls (L. fuscus) breeding in the Netherlands (n = 899). The shades increase in darkness from left to right and correspond approximately to shades of grey, which range from 1 (white) to 20 (black). The data for Lesser Black-backed Gulls are taken from Muusse et al. (2011).

Differences in wing pigmentation

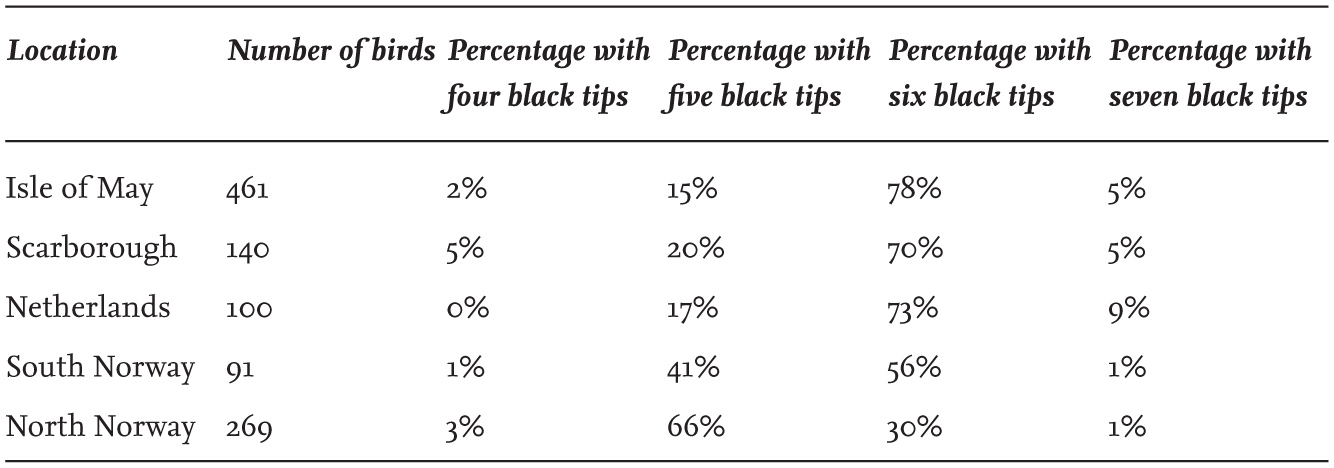

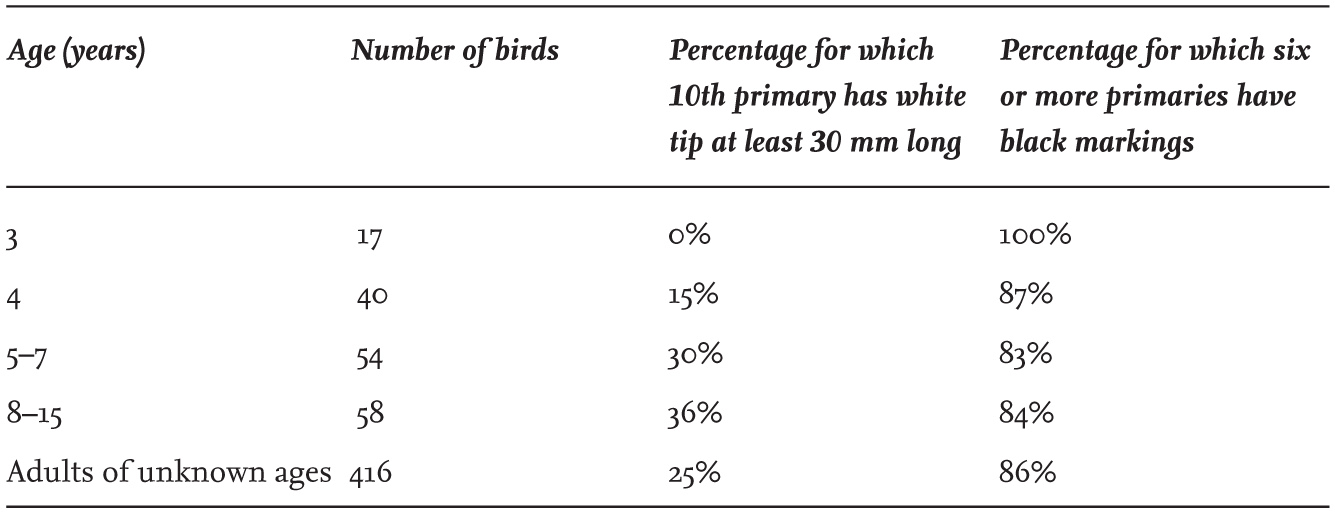

A major source of plumage variation within gull species is the pattern of black or brown pigmentation on the wings of immature individuals. These show progressive changes at each annual moult, until adult plumage is eventually achieved. In addition, this patterning varies appreciably between individuals of the same age, even within a single colony. For example, fully adult Herring Gulls in the same colony showed a range in the number of primaries that are tipped with black pigment (Table 3), and they also showed variation in the extent of white on the tip of the longest (10th) primary. Part of this variation is linked to the age of the birds (Table 4), with change continuing for several years after individuals reach breeding age, but the patterning is not related to gender.

TABLE 3. The percentage of fully adult Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) examined in breeding colonies with different numbers of black-tipped outer primaries. Dutch data from Muusse et al. (2011), Norwegian data mainly from Barth (1975).

TABLE 4. The wing-tip pattern in Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) of known age breeding in colonies in Britain. The extent of white on the tip of the 10th primary tends to increase with age.

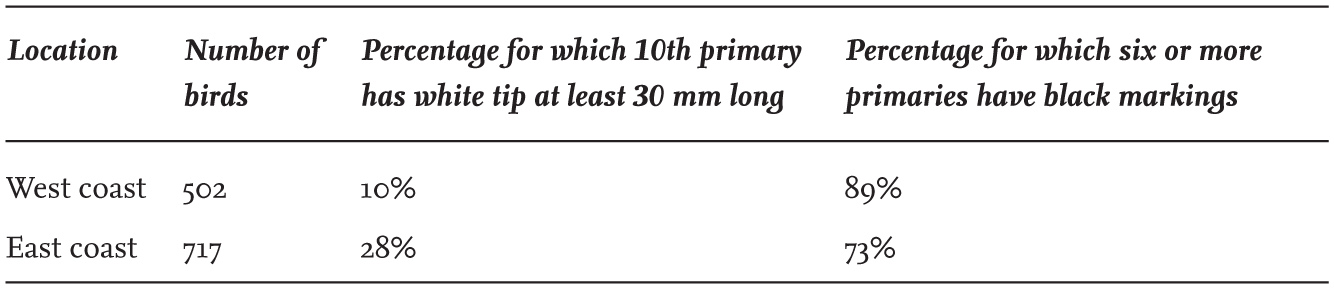

Part of the variation is also geographical, as seen in adult Herring Gulls breeding on the east and west sides of England and Scotland (Table 5). This difference between east and west in the black-and-white patterning on the primaries is maintained in the winter, presumably because the north–south dispersive movements of British Herring Gulls mainly follow either the eastern or the western coastlines, with relatively few individuals crossing between the two coasts. Figs 8 and 9 illustrate the variation in two adult Herring Gulls captured in north-east England, with one showing the thayeri-type pattern on the ninth primary (second from left), where the black does not spread across the whole of the width of the feather.

TABLE 5. Comparison of wing-tip patterns of adult British Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) breeding on the east and west coasts of England and Scotland. The differences in both characters are significant.

FIG 8. The wing-tip pattern of an adult Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) captured in north-east England, showing what is known as the thayeri-type pattern on the ninth primary. The bird was subsequently found breeding in northern Norway. (John Coulson)

FIG 9. A typical wing-tip pattern of a Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) breeding in Scotland, with the 10th primary still growing. (John Coulson)

Differences caused by hybrids

One definition of a biological species is that the individuals can form a group of interbreeding or potentially interbreeding organisms that produce viable offspring. If hybrids occur between two species, such as in the classical case of a horse and a donkey, the hybrid offspring of the two (a mule or hinny) are usually sterile, probably because the two parent species have different numbers of chromosomes. In the case of gulls, hybrids are not uncommon and are reported far more frequently than in major taxa, such as terns. Studies have revealed that Larus gulls have the same number of chromosomes (72) and as a result, hybrids are usually fertile and they have been reported breeding successfully. There are now numerous records of gulls of different species and even different genera pairing and rearing hybrid offspring, as listed below:

Mediterranean Gull × Black-headed Gull

Herring Gull × Lesser Black-backed Gull

Herring Gull × Yellow-legged Gull

Lesser Black-backed Gull × Yellow-legged Gull

Western Gull (Larus occidentalis) × Glaucous-winged Gull

Great Black-backed Gull × American Herring Gull

Herring Gull × Glaucous Gull

Glaucous-winged Gull × Glaucous Gull

American Herring Gull × Kelp Gull

Iceland Gull × Thayer’s Gull

Common Gull × Ring-billed Gull

Mediterranean Gull × Common Gull

Laughing Gull × Black-headed Gull

Laughing Gull × Ring-billed Gull

Herring Gull × Caspian Gull

In most cases, adults that are believed to be hybrids have been recognised by the intermediate nature of their plumage and the colouring of their legs and bill, but in only a very few instances has the plumage been described for adults that are known to be hybrids and were ringed as such before they fledged. It is usually believed that hybrid gulls show intermediate characters of their parents in terms of plumage, bill colour and leg colour, but this is not always the case, and in several instances they display minor characteristics not evident in either parent.

There is little doubt that some hybrids can share similarities with, and resemble, other gull species. As a result, it is sometimes difficult to accept a new sight record of a species from a geographical area where it has not been previously or convincingly been recorded before, and to confirm that it is not a hybrid between species that breed nearby. Rarity committees have a particularly difficult job with gulls, and ideally need DNA samples obtained from feathers of the presumed rarity to be certain of the record.

Some hybrid gulls, when adult, have been known to pair and mate with an individual of one of their parent species, producing offspring known as back-crosses. Even less is known about the plumage of these offspring, but it is likely that they differ both from the original species and from the hybrid parent. Breeding between pairs of hybrid gulls has not been recorded. However, hybridisation and subsequent breeding is likely to produce at least three different types of individuals, all of which vary in some respect from the original parent species as well as from each other. The immature plumages of hybrid gulls are poorly known and in many cases their origin has been assumed only because of their intermediate characteristics.

Eventually, after several generations of breeding, a particular gene can be transferred via the offspring of a hybrid from one of the parent species to the other. This has been recorded in the American Herring Gull, which appears to have acquired a gene from the Great Black-backed Gull in North America, presumably through hybrids between the two species. To date, this gene has not been recorded in the European Herring Gull.

In Belgium and the Netherlands, mixed pairs of Yellow-legged Gulls and either Lesser Black-backed Gulls or Herring Gulls have occurred particularly frequently. For example, more than 15 mixed pairs were reported in Rotterdam annually from 1986 to 1998 (van Swelm, 1998) and more in more recent years, and others have been frequently identified in at least five other colonies in the Netherlands and Belgium. Hybrid individuals that have reached adulthood and that are presumed to be crosses between Yellow-legged and Lesser Black-backed gulls have also been recorded in Belgium breeding with Lesser Black-backed Gulls, producing back-crosses.

Inter-species breeding is more frequent when one of the gull species is rare and spreading into the main range of the other. For example, when Lesser Black-backed Gulls first started to breed in the Netherlands in the 1930s, a few individuals joined large colonies of Herring Gulls and several mixed breeding pairs were recorded. Despite the fact that both species are now numerous and breed in the same colonies, hybrid pairs still occur, although they are infrequent. Very few pairings between these two species have been reported in Britain, except when experimentally induced (see below).

When Herring Gulls spread to Iceland in the 1920s, individuals formed mixed pairs with Glaucous Gulls, and by 1966 about half of the adults there were considered to be hybrids. These were distinctive in showing small but variable amounts of dark pigment on the tips of the primaries (Ingolfsson, 1970).

When Mediterranean Gulls first started to breed in Britain, early pioneers frequently paired with Black-headed Gulls (as they have done so elsewhere). In fact, this is ongoing, as a few individuals continue to spread north from the south coast of England. The recent arrival of a few adult Yellow-legged Gulls in Britain has seen them join both Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull colonies. Again, they have formed mixed pairs that on some occasions have managed to fledge hybrid chicks. Perhaps this inter-species breeding occurs because individuals arriving in new areas are mainly of the same sex and fail to find a mate of the same species.

In a study carried out on the island of Skokholm in south-west Wales, Mike Harris (1970) switched large numbers of eggs between Lesser Black-backed Gull and Herring Gull nests. The chicks that subsequently hatched imprinted on their foster parents and apparently considered that they were the same species, so that when they matured they chose a mate of that species, forming a series of mixed-species pairs. The young produced and reared by these mixed pairs were hybrids between the parent species and usually (but not always) showed plumage and leg colour intermediate between the two. At least 40 of these hybrids later returned to breed on Skokholm and on nearby Skomer, and most paired with adult Herring or Lesser Black-backed gulls. The chicks they produced were back-crosses and, when adult, were more similar to one of the parent species than the first generation of hybrids. While some of these hybrids reared chicks, it is not known whether they and their offspring were less viable. However, as each generation was produced, presumably both parent species incorporated small amounts of the genetic material belonging to the other species into their make-up despite appearing to be ‘pure’ Herring or Lesser Black-backed gulls (as discussed above for the American Herring and Great Black-backed gulls in North America).

BREEDING

Gulls are monogamous, although a few cases of male Kittiwakes breeding simultaneously with two females at different nest sites have been recorded. Pairs of gulls produce only one brood each breeding season, but if their eggs are lost, many will lay a replacement clutch. While most gulls breed annually during a well-defined breeding season, some individuals skip breeding for a year. The exception is the Swallow-tailed Gull on the Galapagos Islands, which does not have a clear-cut breeding season and nests throughout the year, with individuals breeding at nine- to 10-month intervals.

Breeding sites

Gulls typically favour bare ground and areas with short vegetation for nesting, or floating vegetation on lakes or marshes. The main exceptions are Bonaparte’s Gull, which regularly nests in trees; Common, Black-headed and American Herring Gulls, which occasionally nest in low trees at a small number of localities; Kittiwakes, which favour narrow ledges on steep sea cliffs; and Herring, Glaucous and Ivory gulls, which sometimes use larger cliff ledges.

Ground nesting makes gulls particularly susceptible to mammalian predators, and most species nest only at sites where these predators are usually unable to reach the colonies, such as small islands or isolated peninsulas. Gulls vary in their ability to deter avian predators. Adults will attack birds of prey and corvids, but in parts of northern Scandinavia White-tailed Eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) are having an increasing impact on breeding gulls – this is a future risk for Britain, since the species has been reintroduced here and its numbers are increasing. In addition, adult gulls at breeding sites suffer occasional predation from Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus). Ravens and crows are a problem for some smaller gulls, but in general they are attacked and prevented from entering dense gull colonies. Individual Herring, Lesser Black-backed and Great Black-backed gulls, as well as Great Skuas (Stercorarius skua), have developed the ability to reach and prey on eggs and young gulls at otherwise well-protected nesting sites (sometimes even attacking their own species).

Mammalian predators such as Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and Badgers (Meles meles) have now reached some gull colonies in Britain after being absent for many years, and these and the spread of American Mink (Neovison vison) has often resulted in the sudden desertion of sites used by breeding gulls. This desertion may be immediate, while in other cases the decreases in numbers of adults are spread over several years, apparently because new recruits to the colony are deterred by the presence and activity of predators. In particular, Foxes have become very much more abundant in Britain in recent years, and have captured and killed many incubating gulls at night. Six gull species now also nest on buildings in urban areas (here); these have the same characteristics as natural sites, in that mammalian predators cannot normally reach them and they are generally given public protection.

Humans entering gull colonies are not usually attacked by the smaller gulls, which instead tend to fly overhead giving alarm calls. Large gulls do frequently dive at human intruders, however, usually from behind. While they pass closely overhead, they seldom actually strike. I have been struck only once by a large gull, although one of my students was knocked to the ground by a particularly aggressive Lesser Black-backed Gull defending its unfledged chicks.

Colony and nest site fidelity

Adults gulls are highly site faithful, provided that the nesting site remains safe and is not subject to high levels of predation on eggs, young or adults. Males – particularly those that were successful in rearing young in the previous breeding season – tend to return to the same nesting sites. In contrast, young birds are much less likely to return to the place where they were reared as chicks. A proportion – usually dominated by males – does so, and these birds often return to the same part of a large colony in which they were reared. This behaviour is called philopatry, the extent of which is influenced by many factors, including competition for nesting sites and food availability. In the past, the proportion of birds moving elsewhere has often been underestimated because of the much greater difficulty in locating those that have moved. In some species, the majority of the young that survive to breed move to other colonies, with some moving 100 km or more away. In several species, young individuals have been recorded visiting a number of colonies while approaching maturity, including their natal colony, only then to move and breed elsewhere. Such movements are, of course, necessary to form new colonies.

Colonial breeding

Colonial breeding is widespread among gulls, and only a few species regularly breed both as isolated pairs and in colonies. Some gull colonies are composed of mixed species, and the smaller species frequently nest in or alongside colonies of terns. In many gull species, it appears that single pairs cannot breed in isolation and the presence of a group of gulls of the same or even different species is necessary before egg-laying is possible, thus making colonial breeding essential. The main exceptions are Common and Great Black-backed gulls, where a proportion of breeding pairs nest in isolation from others. It is obvious that colonial nesting is not forced upon gull species as a result of shortage of suitable nesting sites, and it is usually regarded that there is an advantage to breeding close together. An obvious reason is that it improves defence of eggs and unfledged young against predation, but while this is evident in deterring Ravens (Corvus corax) and crows, it is less evident that colonial nesting prevents mammalian predators from raiding colonies and consuming eggs, young and even adults.

The reliance upon a group to ensure breeding suggests that stimulation from other individuals is necessary. This was first suggested in 1938 by Frank Fraser Darling, who noted that the display from neighbours within the colony stimulated pairs to breed and in larger groups or colonies to lay eggs earlier, and that it resulted in greater synchrony with neighbouring pairs. He suggested that the effect of this synchrony was that eggs or chicks were available over a shorter time period, and therefore fewer were predated and breeding success was enhanced. At the time, Fraser Darling’s idea appealed to some, but others were critical of the concept. Unfortunately, his original data on Herring and Lesser Black-backed gulls only hinted at this effect, and others later showed that the variations he found between colonies of different sizes could have been produced by chance and were not statistically significant.

In the 1950s, Edward White and I collected information on the timing of breeding in a series of colonies of Kittiwakes. We found that the laying season in large colonies was more spread out than in small ones, the opposite of Fraser Darling’s contention. While some pairs in the larger colonies started laying earlier than those in the smaller ones, pairs of late-breeding birds (which we now know were mainly young, first-time breeders) were recorded in all the colonies studied.

However, we did discover that breeding in smaller groups of 20–50 Kittiwake pairs within a single colony was more synchronous than in the colony as a whole, and that the average breeding date of each of these groups was earlier as the density of pairs increased. This finding suggested that social stimulation was occurring at the more local level, among groups of breeding pairs, and not in the colony as a whole.

I know of no single pair of Kittiwakes that has been recorded breeding in isolation. As a result, it is difficult for members of the species to form new colonies because this requires a group of individuals to be attracted to, and display at, a new potential breeding site before egg-laying can occur. Up to 20 pairs will collect at the site of a potential new colony for a year or more, and before a few of the pairs succeed in building a nest and laying eggs. However, in subsequent years the numbers breeding increase rapidly. In contrast, Herring Gulls sometimes nest in isolation, but these are birds that have bred before. Young Herring Gulls attempting to breed for the first time do not seem to be able to breed without joining a group already breeding together.

Colonial nesting allows gull species to benefit from the stimulation of their neighbours engaging in courtship activity, and probably encourages earlier nesting in some individuals. This was clearly evident in Kittiwakes when observing a pair reuniting at the colony after one member had been away on a fishing trip (Coulson & Dixon, 1979; Coulson, 2001). The birds engaged in a vocal display of calling, which immediately stimulated similar mutual calling in neighbouring pairs. Where Kittiwake nests were denser, the frequency of this stimulation from neighbours was more frequent. Anyone who has visited a Kittiwake colony will recognise the loud, periodic outburst of calling by groups of pairs as a major feature of the pre-laying period.

New colonies of Kittiwakes and Herring Gulls are highly attractive to potential breeders, and as a result they increase rapidly in size. Part of this effect is a result of the low density of breeding birds in a new colony, with relatively large areas available where recruits can settle without aggression from neighbours. As colonies grow, the area available for new recruits within, and at the immediate edge, decreases relative to their size, and their rate of growth decreases over time. Whether this eventually determines the maximum size for colonies of some species is unclear, but remarkably large colonies are known, numbering tens of thousands of pairs. In contrast, Great Black-backed Gull colonies rarely exceed 200 pairs in Britain (although much larger colonies are known in North America), while large colonies of Common Gulls do occur but are exceptional.

Mixed colonies of Herring Gulls and Lesser Black-backed Gulls are common, but the two species show a tendency to select slightly different areas within the colony. On natural sites, they often nest side by side, but the Herring Gull more frequently nests on open ground with little or short vegetation, while the Lesser Black-backed Gull shows a partial preference for areas with taller vegetation. At urban sites, both species frequently nest side by side and there is no obvious or consistent difference in the sites they select. Great Black-backed Gulls often nest in isolation or in small numbers of pairs in colonies of Herring Gulls or Lesser Black-backed Gulls, where they frequently select sites on raised ground.

Terns often nest in association with Black-headed Gulls, with the latter arriving and laying earlier and taking the first choice of sites. However, this is not always the case – the first Black-headed Gulls to nest on Coquet Island in Northumberland did so alongside Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis), and only arrived after the terns had laid.

Age at first breeding and mate fidelity

Within a species, the age at first breeding is variable and can span three or more years. Smaller gulls tend to breed when they are two or three years old, while many of the large gulls do not normally start breeding until they are four or five years old. This long period of immaturity often allows individuals to visit colonies for one or more years before they breed themselves.

The claim that gulls pair for life is not justified. While the same individuals frequently re-form as a pair in successive years, ‘divorce’ often occurs, with both individuals taking new partners. Change of mate also occurs when one partner dies.

Nests

In general, gulls’ nests are often substantial structures composed of plant material collected by the adults nearby or, in some cases, picked up either from the sea surface, on the tideline or from cliff tops. Gulls that breed on marshes and ponds probably start nest-building earlier than those on drier sites, and they produce a platform above the water level on which most of the displaying and courtship takes place. In situations where the water level rises after rain, there is often an attempt by the pair of gulls to build up the height of the nest to keep the eggs dry. However, this is effective only when relatively small increases in the water level occur.

On several occasions I have seen Kittiwakes flying along the coast carrying nest material as far as 15 km from the nearest colony. This contrasts with Herring Gulls, which usually collect plant material for the nest from within their territory, although if it is not available, such as on roofs of buildings, material is collected from further away. Having collected material, adults shape a central hollow in the centre of the nest by compressing the material with their breasts. This hollow is large enough to hold the usual two or three eggs of the clutch together and prevents the eggs from rolling away by accident.