Полная версия

Полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

The general distribution of the two best known groups of insects—the butterflies and the beetles—agrees very closely with that of the birds and mammalia, inasmuch as Celebes forms the eastern limit of a number of Asiatic and Malayan genera, and at the same time the western limit of several Moluccan and Australian genera, the former perhaps preponderating as in the higher animals.

Himalayan Types of Birds and Butterflies in Celebes.—A curious fact of distribution exhibited both among butterflies and birds, is the occurrence in Celebes of species and genera unknown to the adjacent islands, but only found again when we reach the Himalayan mountains or the Indian Peninsula. Among birds we have a small yellow flycatcher (Myialestes helianthea), a flower-pecker (Pachyglossa aureolimbata), a finch (Munia brunneiceps), and a roller (Coracias temminckii), all closely allied to Indian (not Malayan) species,—all the genera, except Munia, being, in fact, unknown in any Malay island. An exactly parallel case is that of a butterfly of the genus Dichorrhagia, which has a very close ally in the Himalayas, but nothing like it in any intervening country. These facts call to mind the similar case of Formosa, where some of its birds and mammals occurred again, under identical or closely allied forms, in the Himalayas; and in both instances they can only be explained by going back to a period when the distribution of these forms was very different from what it is now.

Peculiarities of Shape and Colour in Celebesian Butterflies.—Even more remarkable are the peculiarities of shape and colour in a number of Celebesian butterflies of different genera. These are found to vary all in the same manner, indicating some general cause of variation able to act upon totally distinct groups, and produce upon them all a common result. Nearly thirty species of butterflies, belonging to three different families, have a common modification in the shape of their wings, by which they can be distinguished at a glance from their allies in any other island or country whatever; and all these are larger than the representative forms inhabiting most of the adjacent islands.168 No such remarkable local modification as this is known to occur in any other part of the globe; and whatever may have been its cause, that cause must certainly have been long in action, and have been confined to a limited area. We have here, therefore, another argument in favour of the long-continued isolation of Celebes from all the surrounding islands and continents—a hypothesis which we have seen to afford the best, if not the only, explanation of its peculiar vertebrate fauna.

Concluding Remarks.—If the view here given of the origin of the remarkable Celebesian fauna is correct, we have in this island a fragment of the great eastern continent which has preserved to us, perhaps from Miocene times, some remnants of its ancient animal forms. There is no other example on the globe of an island so closely surrounded by other islands on every side, yet preserving such a marked individuality in its forms of life; while, as regards the special features which characterise its insects, it is, so far as yet known, absolutely unique. Unfortunately very little is known of the botany of Celebes, but it seems probable that its plants will to some extent partake of the speciality which so markedly distinguishes its animals; and there is here a rich field for any botanist who is able to penetrate to the forest-clad mountains of its interior.

APPENDIX TO CHAPTER XX

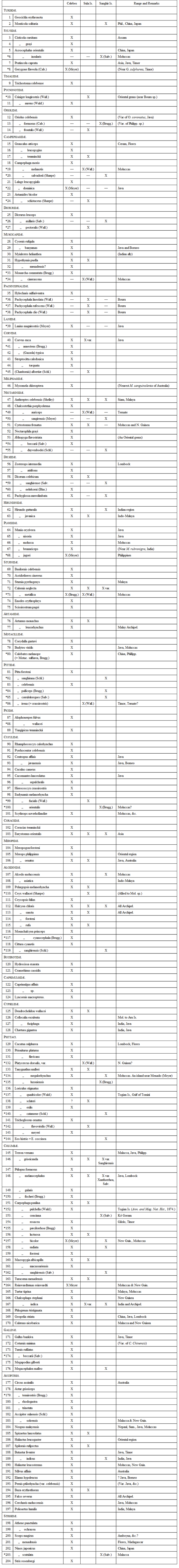

The following list of the Land Birds of Celebes and the adjacent islands which partake of its zoological peculiarities, in which are incorporated all the species discovered up to 1890, has been drawn up from the following sources:—

1. A List of the Birds known to inhabit the Island of Celebes, By Arthur, Viscount Walden, F.R.S. (Trans. Zool. Soc. 1872. Vol. viii. pt. ii.)

2. Intorno al Genere Hermotimia. (Rchb.) Nota di Tommaso Salvadori. (Atti della Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino. Vol x. 1874.)

3. Intorno a due Collezioni di Ucelli di Celebes—Note di Tommaso Salvadori. (Annali del Mus. Civ. di St. Nat. di Genova. Vol. vii. 1875.)

4. Beiträge zur Ornithologie von Celebes und Sangir. Von Dr. Friedrich Brüggemann. Bremen, 1876.

5. Intorno a due piccole Collezioni di Ucelli di Isole Sanghir e di Tifore. Nota di Tommaso Salvadori. (Annali del Mus. Civ. di St. Nat. di Genova. Vol. ix. 1876-77.)

6. Intorno alle Specie di Nettarinie delle Molucche e del Gruppo di Celebes. Note di Tommaso Salvadori. (Atti della Reale Accad. delle Scienze di Torino. Vol. xii. 1877.)

7. Descrizione di tre Nuove Specie di Ucelli, e note intorno ad altre poco conosciute delle Isole Sanghir. Per Tommaso Salvadori. (L. c. Vol. xiii. 1878.)

8. Field Notes on the Birds of Celebes. By A. B. Meyer, M.D., &c. (Ibis, 1879.)

9. On the Collection of Birds made by Dr. Meyer during his Expedition to New Guinea and some neighbouring Islands. By R. Boulder Sharpe. (Mitth. d. kgl. Zool. Mus. Dresden, 1878. Heft 3.) New species from the Sula and Sanghir Islands are described.

10. List of Birds from the Sula Islands (East of Celebes) with Descriptions of the New Species. By Alfred Russel Wallace, F.Z.S. (Proc. Zool. Soc. 1862, p. 333.)

11. The Zoological Record, and "The Ibis" to 1890.

LIST OF LAND BIRDS OF CELEBES

N.B.—The Species marked with an * are not included in Viscount Walden's list. For these only, an authority is usually given.

CHAPTER XXI

ANOMALOUS ISLANDS: NEW ZEALAND

Position and Physical Features of New Zealand—Zoological Character of New Zealand—Mammalia—Wingless Birds Living and Extinct—Recent Existence of the Moa—Past Changes of New Zealand deduced from its Wingless Birds—Birds and Reptiles of New Zealand—Conclusions from the Peculiarities of the New Zealand Fauna.

The fauna of New Zealand has been so recently described, and its bearing on the past history of the islands so fully discussed in my large work already referred to, that it would not be necessary to introduce the subject again, were it not that we now approach it from a somewhat different point of view, and with some important fresh material, which will enable us to arrive at more definite conclusions as to the nature and origin of this remarkable fauna and flora. The present work is, besides, addressed to a wider class of readers than my former volumes, and it would be manifestly incomplete if all reference to one of the most remarkable and interesting of insular faunas was omitted.

The two great islands which mainly constitute New Zealand are together about as large as the kingdom of Italy. They stretch over thirteen degrees of latitude in the warmer portion of the south-temperate zone, their extreme points corresponding to the latitudes of Vienna and Cyprus. Their climate throughout is mild and equable, their vegetation is luxuriant, and deserts or uninhabitable regions are as completely unknown as in our own islands.

The geological structure of these islands has a decidedly continental character. Ancient sedimentary rocks, granite, and modern volcanic formations abound; gold, silver, copper, tin, iron, and coal are plentiful; and there are also some considerable deposits of early or late Tertiary age. The Secondary rocks alone are very scantily developed, and such fragments as exist are chiefly of Cretaceous age, often not clearly separated from the succeeding Eocene beds.

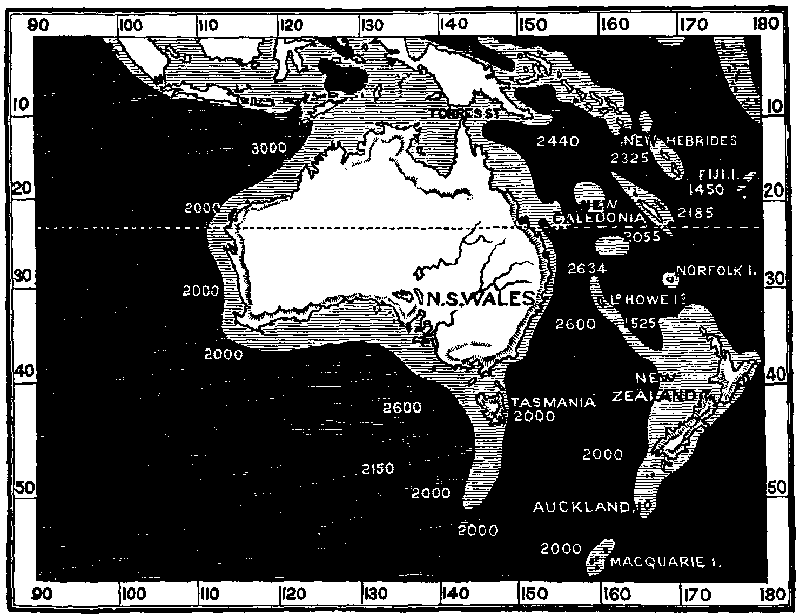

MAP SHOWING DEPTHS OF SEA AROUND AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND.

The light tint indicates a depth of less than 1,000 fathoms.

The dark tint ,, ,, more than 1,000 fathoms.

The position of New Zealand, in the great Southern Ocean, about 1,200 miles distant from the Australian continent, is very isolated. It is surrounded by a moderately deep ocean; but the form of the sea-bottom is peculiar, and may help us in the solution of some of the anomalies presented by its living productions. The line of 200 fathoms encloses the two islands and extends their area considerably; but the 1,000-fathom line, which indicates the land-area that would be produced if the sea-bottom were elevated 6,000 feet, has a very remarkable conformation, extending in a broad mass westward and northward, then sending out a great arm reaching to beyond Lord Howe's Island. Norfolk Island is situated on a moderate-sized bank, while two others, much more extensive, to the north-west approach the great barrier reef, which here carries the 1,000-fathom line more than 300 miles from the coast. It is probable that a bank, less than 1,500 fathoms below the surface, extends over this area, thus forming a connection with tropical Australia and New Guinea. Temperate Australia, on the other hand, is divided from New Zealand by an oceanic gulf about 700 miles wide and between 2,000 and 3,000 fathoms deep. The 2,000-fathom line embraces all the islands immediately round New Zealand as far as the Fijis to the north, while a submarine plateau at a depth somewhere between one and two thousand fathoms stretches southward to the Antarctic continent. Judging from these indications, we should say that the most probable ancient connections of New Zealand were with tropical Australia, New Caledonia, and the Fiji Islands, and perhaps at a still more remote epoch, with the great Southern continent by means of intervening lands and islands; and we shall find that a land-connection or near approximation in these two directions, at remote periods, will serve to explain many of the remarkable anomalies which these islands present.

Zoological Character of New Zealand.—We see, then, that both geologically and geographically New Zealand has more of the character of a "continental" than of an "oceanic" island, yet its zoological characteristics are such as almost to bring it within the latter category—and it is this which gives it its anomalous character. It is usually considered to possess no indigenous mammalia; it has no snakes, and only one frog; it possesses (living or quite recently extinct) an extensive group of birds incapable of flight; and its productions generally are wonderfully isolated, and seem to bear no predominant or close relation to those of Australia or any other continent. These are the characteristics of an oceanic island; and thus we find that the inferences from its physical structure and those from its forms of life directly contradict each other. Let us see how far a closer examination of the latter will enable us to account for this apparent contradiction.

Mammalia of New Zealand.—The only undoubtedly indigenous mammalia appear to be two species of bats, one of which (Scotophilus tuberculatus) is, according to Mr. Dobson, identical with an Australian form, while the other (Mystacina tuberculata) forms a very remarkable and isolated genus of Emballonuridæ, a family which extends throughout all the tropical regions of the globe. The genus Mystacina was formerly considered to belong to the American Phyllostomidæ, but this has been shown to be an error.169 The poverty of New Zealand in bats is very remarkable when compared with our own islands where there are at least twelve distinct species, though we have a far less favourable climate.

Of the existence of truly indigenous land mammals in New Zealand there is at present no positive evidence, but there is some reason to believe that one if not two species may be found there. The Maoris say that before Europeans came to their country a forest-rat abounded and was largely used for food. They believe that their ancestors brought it with them when they first came to the country; but it has now become almost, if not quite, exterminated by the European brown rat. What this native animal was is still somewhat doubtful. Several specimens have been caught at different times which have been declared by the natives to be the true Kiore Maori—as they term it, but these have usually proved on examination to be either the European black rat or some of the native Australian rats which now often find their way on board ships. But within the last few years many skulls of a rat have been obtained from the old Maori cooking-places, and from a cave associated with moa bones; and Captain Hutton, who has examined them, states that they belong to a true Mus, but differ from the Mus rattus. This animal might have been on the islands when the Maoris first arrived, and in that case would be truly indigenous; while the Maori legend of their "ancestors" bringing the rat from their Polynesian home may be altogether a myth invented to account for its presence in the islands, because the only other land mammal which they knew—the dog—was certainly so brought. The question can only be settled by the discovery of remains of a rat in some deposit of an age decidedly anterior to the first arrival of the Maori race in New Zealand.170

Much more interesting is the reported existence in the mountains of the South Island of a small otter-like animal. Dr. Haast has seen its tracks, resembling those of our European otter, at a height of 3,000 feet above the sea in a region never before trodden by man; and the animal itself was seen by two gentlemen near Lake Heron, about seventy miles due west of Christchurch. It was described as being dark brown and the size of a large rabbit. On being struck at with a whip, it uttered a shrill yelping sound and disappeared in the water.171 An animal seen so closely as to be struck at with a whip could hardly have been mistaken for a dog—the only other animal that it could possibly be supposed to have been, and a dog would certainly not have "disappeared in the water." This account, as well as the footsteps, point to an aquatic animal; and if it now frequents only the high alpine lakes and streams, this might explain why it has never yet been captured. Hochstetter also states that it has a native name—Waitoteke—a striking evidence of its actual existence, while a gentleman who lived many years in the district assures me that it is universally believed in by residents in that part of New Zealand. The actual capture of this animal and the determination of its characters and affinities could not fail to aid us greatly in our speculations as to the nature and origin of the New Zealand fauna.172

Wingless Birds, Living and Extinct.—Almost equally valuable with mammalia in affording indications of geographical changes are the wingless birds for which New Zealand is so remarkable. These consist of four species of Apteryx, called by the natives "kiwis,"—creatures which hardly look like birds owing to the apparent absence (externally) of tail or wings and the dense covering of hair-like feathers. They vary in size from that of a small fowl up to that of a turkey, and have a long slightly curved bill, somewhat resembling that of the snipe or ibis. Two species appear to be confined to the South Island, and one to the North Island, but all are becoming scarce, and they will no doubt gradually become extinct. These birds are generally classed with the Struthiones or ostrich tribe, but they form a distinct family, and in many respects differ greatly from all other known birds.

But besides these, a number of other wingless birds, called "moas," inhabited New Zealand during the period of human occupation, and have only recently become extinct. These were much larger birds than the kiwis, and some of them were even larger than the ostrich, a specimen of Dinornis maximus mounted in the British Museum in its natural attitude being eleven feet high. They agreed, however, with the living Apteryx in the character of the pelvis and some other parts of the skeleton, while in their short bill and in some important structural features they resembled the emu of Australia and the cassowaries of New Guinea.173 No less than eleven distinct species of these birds have now been discovered; and their remains exist in such abundance—in recent fluviatile deposits, in old native cooking places, and even scattered on the surface of the ground—that complete skeletons of several of them have been put together, illustrating various periods of growth from the chick up to the adult bird. Feathers have also been found attached to portions of the skin, as well as the stones swallowed by the birds to assist digestion, and eggs, some containing portions of the embryo bird; so that everything confirms the statements of the Maoris—that their ancestors found these birds in abundance on the islands, that they hunted them for food, and that they finally exterminated them only a short time before the arrival of Europeans.174 Bones of Apteryx are also found fossil, but apparently of the same species as the living birds. How far back in geological time these creatures or their ancestral types lived in New Zealand we have as yet no evidence to show. Some specimens have been found under a considerable depth of fluviatile deposits which may be of Quaternary or even of Pliocene age; but this evidently affords us no approximation to the time required for the origin and development of such highly peculiar insular forms.

Past Changes of New Zealand deduced from its Wingless Birds.—It has been well observed by Captain Hutton, in his interesting paper already referred to, that the occurrence of such a number of species of Struthious birds living together in so small a country as New Zealand is altogether unparalleled elsewhere on the globe. This is even more remarkable when we consider that the species are not equally divided between the two islands, for remains of no less than ten out of the eleven known species of Dinornis have been found in a single swamp in the South Island, where also three of the species of Apteryx occur. The New Zealand Struthiones, in fact, very nearly equal in number those of all the rest of the world, and nowhere else do more than three species occur in any one continent or island, while no more than two ever occur in the same district. Thus, there appear to be two closely allied species of ostriches inhabiting Africa and South-western Asia respectively. South America has three species of Rhea, each in a separate district. Australia has an eastern and a western variety of emu, and a cassowary in the north; while eight other cassowaries are known from the islands north of Australia—one from Ceram, two from the Aru Islands, one from Jobie, one from New Britain, and three from New Guinea—but of these last one is confined to the northern and another to the southern part of the island.

This law, of the distribution of allied species in separate areas—which is found to apply more or less accurately to all classes of animals—is so entirely opposed to the crowding together of no less that fifteen species of wingless birds in the small area of New Zealand, that the idea is at once suggested of great geographical changes. Captain Hutton points out that if the islands from Ceram to New Britain were to become joined together, we should have a large number of species of cassowary (perhaps several more than are yet discovered) in one land area. If now this land were gradually to be submerged, leaving a central elevated region, the different species would become crowded together in this portion just as the moas and kiwis were in New Zealand. But we also require, at some remote epoch, a more or less complete union of the islands now inhabited by the separate species of cassowaries, in order that the common ancestral form which afterwards became modified into these species, could have reached the places where they are now found; and this gives us an idea of the complete series of changes through which New Zealand is believed to have passed in order to bring about its abnormally dense population of wingless birds. First, we must suppose a land connection with some country inhabited by struthious birds, from which the ancestral forms might be derived; secondly, a separation into many considerable islands, in which the various distinct species might become differentiated; thirdly, an elevation bringing about the union of these islands to unite the distinct species in one area; and fourthly, a subsidence of a large part of the area, leaving the present islands with the various species crowded together.

If New Zealand has really gone through such a series of changes as here suggested, some proofs of it might perhaps be obtained in the outlying islands which were once, presumably, joined with it. And this gives great importance to the statement of the aborigines of the Chatham Islands, that the Apteryx formerly lived there but was exterminated about 1835. It is to be hoped that some search will be made here and also in Norfolk Island, in both of which it is not improbable remains either of Apteryx or Dinornis might be discovered.

So far we find nothing to object to in the speculations of Captain Hutton, with which, on the contrary, we almost wholly concur; but we cannot follow him when he goes on to suggest an Antarctic continent uniting New Zealand and Australia with South America, and probably also with South Africa, in order to explain the existing distribution of struthious birds. Our best anatomists, as we have seen, agree that both Dinornis and Apteryx are more nearly allied to the cassowaries and emus than to the ostriches and rheas; and we see that the form of the sea-bottom suggests a former connection with North Australia and New Guinea—the very region where these types most abound, and where in all probability they originated. The suggestion that all the struthious birds of the world sprang from a common ancestor at no very remote period, and that their existing distribution is due to direct land communication between the countries they now inhabit, is one utterly opposed to all sound principles of reasoning in questions of geographical distribution. For it depends upon two assumptions, both of which are at least doubtful, if not certainly false—the first, that their distribution over the globe has never in past ages been very different from what it is now; and the second, that the ancestral forms of these birds never had the power of flight. As to the first assumption, we have found in almost every case that groups now scattered over two or more continents formerly lived in intervening areas of existing land. Thus the marsupials of South America and Australia are connected by forms which lived in North America and Europe; the camels of Asia and the llamas of the Andes had many extinct common ancestors in North America; the lemurs of Africa and Asia had their ancestors in Europe, as had the trogons of South America, Africa, and tropical Asia. But besides this general evidence we have direct proof that the struthious birds had a wider range in past times than now. Remains of extinct rheas have been found in Central Brazil, and those of ostriches in North India; while remains, believed to be of struthious birds, are found in the Eocene deposits of England; and the Cretaceous rocks of North America have yielded the extraordinary toothed bird, Hesperornis, which Professor O. Marsh declares to have been "a carnivorous swimming ostrich."

As to the second point, we have the remarkable fact that all known birds of this group have not only the rudiments of wing-bones, but also the rudiments of wings, that is, an external limb bearing rigid quills or largely-developed plumes. In the cassowary these wing-feathers are reduced to long spines like porcupine-quills, while even in the Apteryx, the minute external wing bears a series of nearly twenty stiff quill-like feathers.175 These facts render it almost certain that the struthious birds do not owe their imperfect wings to a direct evolution from a reptilian type, but to a retrograde development from some low form of winged birds, analogous to that which has produced the dodo and the solitaire from the more highly-developed pigeon-type. Professor Marsh has proved, that so far back as the Cretaceous period, the two great forms of birds—those with a keeled sternum and fairly-developed wings, and those with a convex keel-less sternum and rudimentary wings—already existed side by side; while in the still earlier Archæopteryx of the Jurassic period we have a bird with well-developed wings, and therefore probably with a keeled sternum. We are evidently, therefore, very far from a knowledge of the earliest stages of bird life, and our acquaintance with the various forms that have existed is scanty in the extreme; but we may be sure that birds acquired wings, and feathers, and some power of flight, before they developed a keeled sternum, since we see that bats with no such keel fly very well. Since, therefore, the struthious birds all have perfect feathers, and all have rudimentary wings, which are anatomically those of true birds, not the rudimentary fore-legs of reptiles, and since we know that in many higher groups of birds—as the pigeons and the rails—the wings have become more or less aborted, and the keel of the sternum greatly reduced in size by disuse, it seems probable that the very remote ancestors of the rhea, the cassowary, and the apteryx, were true flying birds, although not perhaps provided with a keeled sternum, or possessing very great powers of flight. But in addition to the possible ancestral power of flight, we have the undoubted fact that the rhea and the emu both swim freely, the former having been seen swimming from island to island off the coast of Patagonia. This, taken in connection with the wonderful aquatic ostrich of the Cretaceous period discovered by Professor Marsh, opens up fresh possibilities of migration; while the immense antiquity thus given to the group and their universal distribution in past time, renders all suggestions of special modes of communication between the parts of the globe in which their scattered remnants now happen to exist, altogether superfluous and misleading.