Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Island Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

Extinct Birds.—These three islands are, however, preeminently remarkable as having been the home of a group of large ground-birds, quite incapable of flight, and altogether unlike anything found elsewhere on the globe; and which, though once very abundant, have become totally extinct within the last two hundred years. The best known of these birds is the dodo, which inhabited Mauritius; while allied species certainly lived in Bourbon and Rodriguez, abundant remains of the species of the latter island—the "solitaire," having been discovered, corresponding with the figure and description given of it by Legouat, who resided in Rodriguez in 1692. These birds constitute a distinct family, Dididæ, allied to the pigeons but very isolated. They were quite defenceless, and were rapidly exterminated when man introduced dogs, pigs, and cats into the island, and himself sought them for food. The fact that such perfectly unprotected creatures survived in great abundance to a quite recent period in these three islands only, while there is no evidence of their ever having inhabited any other countries whatever, is itself almost demonstrative that Mauritius, Bourbon, and Rodriguez are very ancient but truly oceanic islands. From what we know of the general similarity of Miocene birds to living genera and families, it seems clear that the origin of so remarkable a type as the dodos must date back to early Tertiary times. If we suppose some ancestral ground-feeding pigeon of large size to have reached the group by means of intervening islands afterwards submerged, and to have thenceforth remained to increase and multiply unchecked by the attacks of any more powerful animals, we can well understand that the wings, being useless, would in time become almost aborted.162 It is also not improbable that this process would be aided by natural selection, because the use of wings might be absolutely prejudicial to the birds in their new home. Those that flew up into trees to roost, or tried to cross over the mouths of rivers, might be blown out to sea and destroyed, especially during the hurricanes which have probably always more or less devastated the islands; while on the other hand the more bulky and short-winged individuals, who took to sleeping on the ground in the forest, would be preserved from such dangers, and perhaps also from the attacks of birds of prey which may always have visited the islands. But whether or no this was the mode by which these singular birds acquired their actual form and structure, it is perfectly certain that their existence and development depended on complete isolation and on freedom from the attacks of enemies. We have no single example of such defenceless birds having ever existed on a continent at any geological period, whereas analogous though totally distinct forms do exist in New Zealand, where enemies are equally wanting. On the other hand, every continent has always produced abundance of carnivora adapted to prey upon the herbivorous animals inhabiting it at the same period; and we may therefore be sure that these islands have never formed part of a continent during any portion of the time when the dodos inhabited them.

It is a remarkable thing that an ornithologist of Dr. Hartlaub's reputation, looking at the subject from a purely ornithological point of view, should yet entirely ignore the evidence of these wonderful and unique birds against his own theory, when he so confidently characterises Lemuria as "that sunken land, which, containing parts of Africa, must have extended far eastward over Southern India and Ceylon, and the highest points of which we recognise in the volcanic peaks of Bourbon and Mauritius, and in the central range of Madagascar itself—the last resorts of the mostly extinct Lemurine race which formerly peopled it."163 It is here implied that lemurs formerly inhabited Bourbon and Mauritius, but of this there is not a particle of evidence, and we feel pretty sure that had they done so the dodos would never have been developed there. In Madagascar there are no traces of dodos, while there are remains of extinct gigantic struthious birds of the genus Æpyornis, which were no doubt as well able to protect themselves against the smaller carnivora as are the ostriches, emus, and cassowaries in their respective countries at the present day.

The whole of the evidence at our command, therefore, tends to establish in a very complete manner the "oceanic" character of the three islands—Mauritius, Bourbon, and Rodriguez, and that they have never formed part of "Lemuria" or of any continent.

Reptiles.—Mauritius, like Bourbon, has lizards, some of which are peculiar species; but no snakes, and no frogs or toads but such as have been introduced.164 Strange to say, however, a small islet called Round Island, only about a mile across, and situated about fourteen miles north-east of Mauritius, possesses a snake which is not only unknown in Mauritius, but also in any other part of the world, being altogether confined to this minute islet! It belongs to the boa family, and forms a peculiar and very distinct genus, Casaria, whose nearest allies seem to be the Ungalia of Cuba and Bolyeria of Australia. It is hardly possible to believe that this serpent has very long maintained itself on so small an island; and though we have no record of its existence on Mauritius, it may very well have inhabited the lowland forests without being met with by the early settlers; and the introduction of swine, which soon ran wild and effected the final destruction of the dodo, may also have been fatal to this snake. It is, however, now almost certainly confined to the one small islet, and is probably the land-vertebrate of most restricted distribution on the globe.

On the same island there is a small lizard, Scelotes bojeri, recorded also from Mauritius and Bourbon, though it appears to be rare in both islands; but a gecko, Phelsuma guentheri, is restricted to the island. As Round Island is connected with Mauritius by a bank under a hundred fathoms below the surface, it has probably been once joined to it, and when first separated would have been both much larger and much nearer the main island, circumstances which would greatly facilitate the transmission of these reptiles to their present dwelling-place, where they have been able to maintain themselves owing to the complete absence of competition, while some of them have become extinct in the larger island.

Flora of Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands.—The botany of the great island of Madagascar has been perhaps more thoroughly explored than that of the opposite coasts of Africa, so that its peculiarities may not be really so great as they now appear to be. Yet there can be no doubt of its extreme richness and grandeur, its remarkable speciality, and its anomalous external relations. It is characterised by a great abundance of forest-trees and shrubs of peculiar genera or species, and often adorned with magnificent flowers. Some of these are allied to African forms, others to those of Asia, and it is said that of the two affinities the latter preponderates. But there are also, as in the animal world, some decided South American relations, while other groups point to Australia, or are altogether isolated.

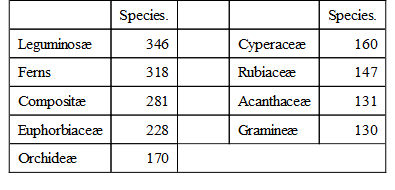

No less than 3,740 flowering plants are now known from Madagascar with 360 ferns and fern-allies. The most abundant natural orders are the following:

The flora contains representatives of 144 natural orders and 970 genera, one of the former and 148 of the latter being peculiar to the island. The peculiar order, Chælnaceæ, comprises seven genera and twenty-four species; while Rubiaceæ and Compositæ have the largest number of peculiar genera, followed by Leguminosæ and Melastomaceæ. Nearly three-fourths of the species are endemic.

Beautiful flowers are not conspicuous in the flora of Madagascar, though it contains several magnificent flowering plants. A shrub with the dreadful name Harpagophytum Grandidieri has bunches of gorgeous red flowers; Tristellateia madagascariensis is a climbing plant with spikes of rich yellow flowers; while Poinciana regia, a tall tree, Rhodolæna altivola and Astrapœa Wallichii, shrubs, are among the most magnificent flowering plants in the world. Disa Buchenaviana, Commelina madagascarica, and Tachiadenus platypterus are fine blue-flowered plants, while the superb orchid Angræcum sesquipedale, Vinca rosea, Euphorbia splendens, and Stephanotis floribunda, have been long cultivated in our hot-houses. There are also many handsome Combretaceæ, Rubiaceæ, and Leguminosæ; but, as in most tropical regions, this wealth of floral beauty has to be searched for, and produces little effect in the landscape.

The affinities of the Madagascar flora are to a great extent in accordance with those of the fauna. The tropical portion of the flora agrees closely with that of tropical Africa, while the plants of the highlands are equally allied to those of the Cape and of the mountains of Central Africa. Some Asiatic types are present which do not occur in Africa; and even the curious American affinities of some of the animals are reproduced in the vegetable kingdom. These last are so interesting that they deserve to be enumerated. An American genus of Euphorbiaceæ, Omphalea, has one species in Madagascar, and Pedilanthus, another genus of the same natural order, has a similar distribution. Myrosma, an American genus of Scitamineæ has one Madagascar species; while the celebrated "travellers' tree," Ravenala madagascariensis, belonging to the order Musaceæ, has its nearest ally in a plant inhabiting N. Brazil and Guiana. Echinolæna, a genus of grasses, has the same distribution.165

Of the flora of the smaller Madagascarian islands we possess a fuller account, owing to the recent publication of Mr. Baker's Flora of the Mauritius and the Seychelles, including also Rodriguez. The total number of species in this flora is 1,058, more than half of which (536) are exclusively Mascarene—that is, found only in some of the islands of the Madagascar group, while nearly a third (304) are endemic or confined to single islands. Of the widespread plants sixty-six are found in Africa but not in Asia, and eighty-six in Asia but not in Africa, showing a similar Asiatic preponderance to what is said to occur in Madagascar. With the genera, however, the proportions are different, for I find by going through the whole of the generic distributions as given by Mr. Baker, that out of the 440 genera of wild plants fifty are endemic, twenty-two are Asiatic but not African, while twenty-eight are African but not Asiatic. This implies that the more ancient connection has been on the side of Africa, while a more recent immigration, shown by identity of species, has come from the side of Asia; and it is already certain that when the flora of Madagascar is more thoroughly worked out, a still greater African preponderance will be found in that island.

A few Mascarene genera are found elsewhere only in South America, Australia, or Polynesia; and there are also a considerable number of genera whose metropolis is South America, but which are represented by one or more species in Madagascar, and by a single often widely distributed species in Africa. This fact throws light upon the problem offered by those mammals, reptiles, and insects of Madagascar which now have their only allies in South America, since the two cases would be exactly parallel were the African plants to become extinct. Plants, however, are undoubtedly more long-lived specifically than animals—especially the more highly organised groups, and are less liable to complete extinction through the attacks of enemies or through changes of climate or of physical geography; hence we find comparatively few cases in which groups of Madagascar plants have their only allies in such distant regions as America and Australia, while such cases are numerous among animals, owing to the extinction of the allied forms in intervening areas, for which extinction, as we have already shown, ample cause can be assigned.

Curious Relations of Mascarene Plants.—Among the curious affinities of Mascarene plants we have culled the following from Mr. Baker's volume. Trochetia, a genus of Sterculiaceæ, has four species in Mauritius, one in Madagascar, and one in the remote island of St. Helena. Mathurina, a genus of Turneraceæ, consisting of a single species peculiar to Rodriguez, has its nearest ally in another monotypic genus, Erblichia, confined to Central America. Siegesbeckia, one of the Compositæ, consists of two species, one inhabiting the Mascarene islands, the other Peru. Labourdonasia, a genus of Sapotaceæ, has two species in Mauritius, one in Natal, and one in Cuba. Nesogenes, belonging to the verbena family, has one species in Rodriguez and one in Polynesia. Mespilodaphne, an extensive genus of Lauraceæ, has six species in the Mascarene islands, and all the rest (about fifty species) in South America. Nepenthes, the well-known pitcher plants, are found chiefly in the Malay Islands, South China, and Ceylon, with species in the Seychelles Islands, and in Madagascar. Milla, a large genus of Liliaceæ, is exclusively American, except one species found in Mauritius and Bourbon. Agauria, a genus of Ericaceæ, is found in Madagascar, the Mascarene islands, the plateau of Central Africa, and the Camaroon Mountains in West Africa. An acacia, found in Mauritius and Bourbon (A. heterophylla), can hardly be separated specifically from Acacia koa of the Sandwich Islands. The genus Pandanus, or screw-pine, has sixteen species in the three islands—Mauritius, Rodriguez, and the Seychelles—all being peculiar, and none ranging beyond a single island. Of palms there are fifteen species belonging to ten genera, and all these genera are peculiar to the islands. We have here ample evidence that plants exhibit the same anomalies of distribution in these islands as do the animals, though in a smaller proportion; while they also exhibit some of the transitional stages by which these anomalies have, in all probability, been brought about, rendering quite unnecessary any other changes in the distribution of sea and land than physical and geological evidence warrants.166

Fragmentary Character of the Mascarene Flora.—Although the peculiar character and affinities of the vegetation of these islands is sufficiently apparent, there can be little doubt that we only possess a fragment of the rich flora which once adorned them. The cultivation of sugar, and other tropical products, has led to the clearing away of the virgin forests from all the lowlands, plateaus, and accessible slopes of the mountains, so that remains of the aboriginal woodlands only linger in the recesses of the hills, and numbers of forest-haunting plants must inevitably have been exterminated. The result is, that nearly three hundred species of foreign plants have run wild in Mauritius, and have in their turn helped to extinguish the native species. In the Seychelles, too, the indigenous flora has been almost entirely destroyed in most of the islands, although the peculiar palms, from their longevity and comparative hardiness, have survived. Mr. Geoffrey Nevill tells us, that at Mahé, and most of the other islands visited by him, it was only in a few spots near the summits of the hills that he could perceive any remains of the ancient flora. Pine-apples, cinnamon, bamboos, and other plants have obtained a firm footing, covering large tracts of country and killing the more delicate native flowers and ferns. The pine-apple, especially, grows almost to the tops of the mountains. Where the timber and shrubs have been destroyed, the water falling on the surface immediately cuts channels, runs off rapidly, and causes the land to become dry and arid; and the same effect is largely seen both in Mauritius and Bourbon, where, originally, dense forest covered the entire surface, and perennial moisture, with its ever-accompanying luxuriance of vegetation, prevailed.

Flora of Madagascar Allied to that of South Africa.—In my Geographical Distribution of Animals I have remarked on the relation between the insects of Madagascar and those of south temperate Africa, and have speculated on a great southern extension of the continent at the time when Madagascar was united with it. As supporting this view I now quote Mr. Bentham's remarks on the Compositæ. He says: "The connections of the Mascarene endemic Compositæ, especially those of Madagascar itself, are eminently with the southern and sub-tropical African races; the more tropical races, Plucheineæ, &c., may be rather more of an Asiatic type." He further says that the Composite flora is almost as strictly endemic as that of the Sandwich Islands, and that it is much diversified, with evidences of great antiquity, while it shows insular characteristics in the tendency to tall shrubby or arborescent forms in several of the endemic or prevailing genera.

Preponderance of Ferns in the Mascarene Flora.—A striking character of the flora of these smaller Mascarene islands is the great preponderance of ferns, and next to them of orchideæ. The following figures are taken from Mr. Baker's Flora for Mauritius and the Seychelles, and from an estimate by M. Frappier of the flora of Bourbon given in Maillard's volume already quoted:—

The cause of the great preponderance of ferns in oceanic islands has already been discussed in my book on Tropical Nature; and we have seen that Mauritius, Bourbon, and Rodriguez must be classed as such, though from their proximity to Madagascar they have to be considered as satellites to that great island. The abundance of orchids, the reverse of what occurs in remoter oceanic islands, may be in part due to analogous causes. Their usually minute and abundant seeds would be as easily carried by the wind as the spores of ferns, and their frequent epiphytic habit affords them an endless variety of stations on which to vegetate, and at the same time removes them in a great measure from the competition of other plants. When, therefore, the climate is sufficiently moist and equable, and there is a luxuriant forest vegetation, we may expect to find orchids plentiful on such tropical islands as possess an abundance of insects adapted to fertilise them, and which are not too far removed from other lands or continents from which their seeds might be conveyed.

Concluding Remarks on Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands.—There is probably no portion of the globe that contains within itself so many and such varied features of interest connected with geographical distribution, or which so well illustrates the mode of solving the problems it presents, as the comparatively small insular region which comprises the great island of Madagascar and the smaller islands and island-groups which immediately surround it. In Madagascar we have a continental island of the first rank, and undoubtedly of immense antiquity; we have detached fragments of this island in the Comoros and Aldabra; in the Seychelles we have the fragments of another very ancient island, which may perhaps never have been continental; in Mauritius, Bourbon, and Rodriguez we have three undoubtedly oceanic islands; while in the extensive banks and coral reefs of Cargados, Saya de Malha, the Chagos, and the Maldive Isles, we have indications of the submergence of many large islands which may have aided in the transmission of organisms from the Indian Peninsula. But between and around all these islands we have depths of 2,500 fathoms and upwards, which renders it very improbable that there has ever been here a continuous land surface, at all events during the Tertiary or Secondary periods of geology.

It is most interesting and satisfactory to find that this conclusion, arrived at solely by a study of the form of the sea-bottom and the general principle of oceanic permanence, is fully supported by the evidence of the organic productions of the several islands; because it gives us confidence in those principles, and helps to supply us with a practical demonstration of them. We find that the entire group contains just that amount of Indian forms which could well have passed from island to island; that many of these forms are slightly modified species, indicating that the migration occurred during late Tertiary times, while others are distinct genera, indicating a more ancient connection; but in no one case do we find animals which necessitate an actual land-connection, while the numerous Indian types of mammalia, reptiles, birds, and insects, which must certainly have passed over had there been such an actual land-connection, are totally wanting. The one fact which has been supposed to require such a connection—the distribution of the lemurs—can be far more naturally explained by a general dispersion of the group from Europe, where we know it existed in Eocene times; and such an explanation applies equally to the affinity of the Insectivora of Madagascar and Cuba; the snakes (Herpetodryas, &c.) of Madagascar and America; and the lizards (Cryptoblepharus) of Mauritius and Australia. To suppose, in all these cases, and in many others, a direct land-connection, is really absurd, because we have the evidence afforded by geology of wide differences of distribution directly we pass beyond the most recent deposits; and when we go back to Mesozoic—and still more to Palæozoic—times, the majority of the groups of animals and plants appear to have had a world-wide range. A large number of our European Miocene genera of vertebrates were also Indian or African, or even American; the South American Tertiary fauna contained many European types; while many Mesozoic reptiles and mollusca ranged from Europe and North America to Australia and New Zealand.

By very good evidence (the occurrence of wide areas of marine deposits of Eocene age), geologists have established the fact that Africa was cut off from Europe and Asia by an arm of the sea in early Tertiary times, forming a large island-continent. By the evidence of abundant organic remains we know that all the types of large mammalia now found in Africa (but which are absent from Madagascar) inhabited Europe and Asia, and many of them also North America, in the Miocene period. At a still earlier epoch Africa may have received its lower types of mammals—lemurs, insectivora, and small carnivora, together with its ancestral struthious birds, and its reptiles and insects of American or Australian affinity; and at this period it was joined to Madagascar. Before the later continental period of Africa, Madagascar had become an island; and thus, when the large mammalia from the northern continent overran Africa, they were prevented from reaching Madagascar, which thenceforth was enabled to develop its singular forms of low-type mammalia, its gigantic ostrich-like Æpyornis, its isolated birds, its remarkable insects, and its rich and peculiar flora. From it the adjacent islands received such organisms as could cross the sea; while they transmitted to Madagascar some of the Indian birds and insects which had reached them.

The method we have followed in these investigations is to accept the results of geological and palæontological science, and the ascertained facts as to the powers of dispersal of the various animal groups; to take full account of the laws of evolution as affecting distribution, and of the various ocean depths as implying recent or remote union of islands with their adjacent continents; and the result is, that wherever we possess a sufficient knowledge of these various classes of evidence, we find it possible to give a connected and intelligible explanation of all the most striking peculiarities of the organic world. In Madagascar we have undoubtedly one of the most difficult of these problems; but we have, I think, fairly met and conquered most of its difficulties. The complexity of the organic relations of this island is due, partly to its having derived its animal forms from two distinct sources—from one continent through a direct land-connection, and from another by means of intervening islands now submerged; but, mainly to the fact of its having been separated from a continent which is now, zoologically, in a very different condition from that which prevailed at the time of the separation; and to its having been thus able to preserve a number of types which may date back to the Eocene, or even to the Cretaceous, period. Some of these types have become altogether extinct elsewhere; others have spread far and wide over the globe, and have survived only in a few remote countries—and especially in those which have been more or less secured by their isolated position from the incursions of the more highly-developed forms of later times. This explains why it is that the nearest allies of the Madagascar fauna and flora are now so often to be found in South America or Australia—countries in which low forms of mammalia and birds still largely prevail;—it being on account of the long-continued isolation of all these countries that similar forms (descendants of ancient types) are preserved in them. Had the numerous suggested continental extensions connecting these remote continents at various geological periods been realities, the result would have been that all these interesting archaic forms, all these defenceless insular types, would long ago have been exterminated, and one comparatively monotonous fauna have reigned over the whole earth. So far from explaining the anomalous facts, the alleged continental extensions, had they existed, would have left no such facts to be explained.