Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Island Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

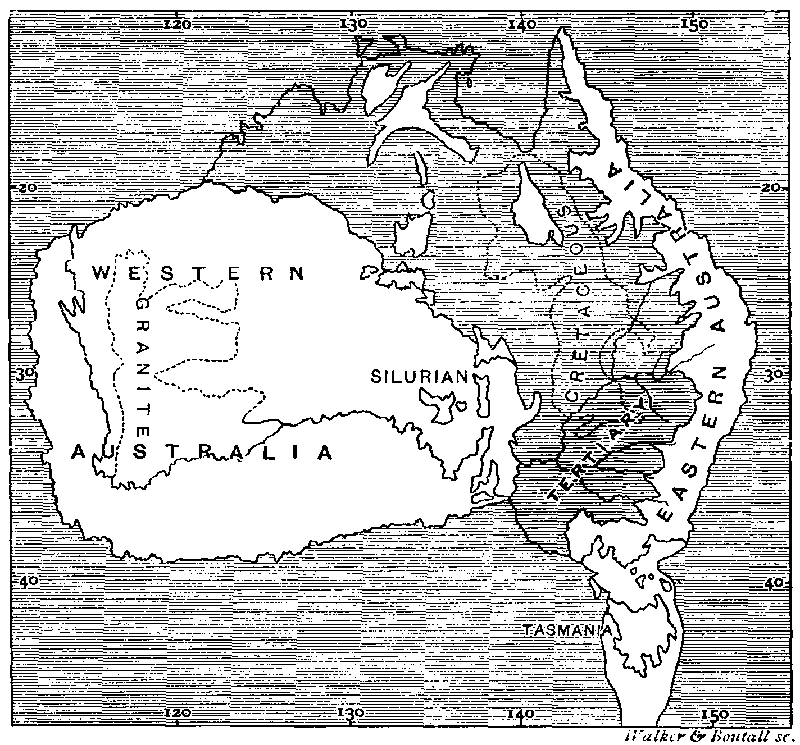

MAP SHOWING THE PROBABLE CONDITION OF AUSTRALIA DURING THE CRETACEOUS AND EARLY TERTIARY PERIODS.

The white portions represent land; the shaded parts sea.

The existing land of Australia is shown in outline.

The eastern and the western islands—with which we are now chiefly concerned—would then differ considerably in their vegetation and animal life. The western and more ancient land already possessed, in its main features, the peculiar Australian flora, and also the ancestral forms of its strange marsupial fauna, both of which it had probably received at some earlier epoch by a temporary union with the Asiatic continent over what is now the Java sea. Eastern Australia, on the other hand, possessed only the rudiments of its existing mixed flora, derived from three distinct sources. Some important fragments of the typical Australian vegetation had reached it across the marine strait, and had spread widely owing to the soil, climate and general conditions being exactly suited to it: from the north and north-east a tropical vegetation of Polynesian type had occupied suitable areas in the north; while the extension southward of the Tasmanian peninsula, accompanied, probably, as now, with lofty mountains, favoured the immigration of south-temperate forms from whatever Antarctic lands or islands then existed. This supposition is strikingly in harmony with what is known of the ancient flora of this portion of Australia. In deposits supposed to be of Eocene age in New South Wales and Victoria fossil plants have been found showing a very different vegetation from that now existing. Along with a few Australian types—such as Pittosporum, Knightia, and Eucalyptus, there occur birches, alders, oaks, and beeches; while in Tasmania in freshwater limestone, apparently of Miocene age, are found willows, alders, birches, oaks, and beeches,184 all except the latter genus (Fagus) now quite extinct in Australia.185 These temperate forms probably indicate a more oceanic climate, cooler and moister than at present. The union with Western Australia and the establishment of an arid interior by modifying the climate may have led to the extinction of many of these forms and their replacement by special Australian types more suited to the new conditions.

At this time the marsupial fauna had not yet reached this eastern land, which was, however, occupied in the north by some ancestral struthious birds, which had entered it by way of New Guinea through some very ancient continental extension, and of which the emu, the cassowaries, the extinct Dromornis of Queensland, and the moas and kiwis of New Zealand, are the modified descendants.

The Origin of the Australian Element in the New Zealand Flora.—We have now brought down the history of Australia, as deduced from its geological structure and the main features of its existing and Tertiary flora, to the period when New Zealand was first brought into close connection with it, by means of a great north-western extension of that country, which, as already explained in our last chapter, is so clearly indicated by the form of the sea bottom (See Map, p. 471). The condition of New Zealand previous to this event is very obscure. That it had long existed as a more or less extensive land is indicated by its ancient sedimentary rocks; while the very small areas occupied by Jurassic and Cretaceous deposits, imply that much of the present land was then also above the sea-level. The country had probably at that time a scanty vegetation of mixed Antarctic and Polynesian origin; but now, for the first time, it would be open to the free immigration of such Australian types as were suitable to its climate, and which had already reached the tropical and sub-tropical portions of the Eastern Australian island. It is here that we obtain the clue to those strange anomalies and contradictions presented by the New Zealand flora in its relation to Australia, which have been so clearly set forth by Sir Joseph Hooker, and which have so puzzled botanists to account for. But these apparent anomalies cease to present any difficulty when we see that the Australian plants in New Zealand were acquired, not directly, but, as it were, at second hand, by union with an island which itself had as yet only received a portion of its existing flora. And then, further difficulties were placed in the way of New Zealand receiving such an adequate representation of that portion of the flora which had reached East Australia as its climate and position entitled it to, by the fact of the union being, not with the temperate, but with the tropical and sub-tropical portions of that island, so that only those groups could be acquired which were less exclusively temperate, and had already established themselves in the warmer portion of their new home186.

It is therefore no matter of surprise, but exactly what we should expect, that the great mass of pre-eminently temperate Australian genera should be absent from New Zealand, including the whole of such important families as, Dilleniaceæ, Tremandreæ, Buettneriacæ, Polygaleæ, Casuarineæ and Hæmodoraceæ; while others, such as Rutaceæ, Stackhousieæ, Rhamneæ, Myrtaceæ, Proteaceæ, and Santalaceæ, are represented by only a few species. Thus, too, we can explain the absence of all the peculiar Australian Leguminosæ; for these were still mainly confined to the great western island, along with the peculiar Acacias and Eucalypti, which at a later period spread over the whole continent. It is equally accordant with the view we are maintaining, that among the groups which Sir Joseph Hooker enumerates as "keeping up the features of extra tropical Australia in its tropical quarter," several should have reached New Zealand, such as Drosera, some Pittosporeæ and Myoporineæ, with a few Proteaceæ, Loganiaceæ, and Restiaceæ; for most of these are not only found in tropical Australia, but also in the Malayan and Pacific islands.

Tropical Character of the New Zealand Flora Explained.—In this origin of the New Zealand fauna by a north-western route from North-eastern Australia, we find also an explanation of the remarkable number of tropical groups of plants found there: for though, as Sir Joseph Hooker has shown, a moist and uniform climate favours the extension of tropical forms in the temperate zone, yet some means must be afforded them for reaching a temperate island. On carefully going through the Handbook, and comparing its indications with those of Bentham's Flora Australiensis, I find that there are in New Zealand thirty-eight thoroughly tropical genera, thirty-three of which are found in Australia—mostly in the tropical portion of it, though a few are temperate, and these may have reached it through New Zealand187. To these we must add thirty-two more genera, which, though chiefly developed in temperate Australia, extend into the tropical or sub-tropical portions of it, and may well have reached New Zealand by the same route.

On the other hand we find but few New Zealand genera certainly derived from Australia which are especially temperate, and it may be as well to give a list of such as do occur with a few remarks. They are sixteen in number, as follows:—

1. Pennantia (1 sp.). This genus has a species in Norfolk Island, indicating perhaps its former extension to the north-west.

2. Pomaderris (3 sp.). One species inhabits Victoria and New Zealand, indicating recent trans-oceanic migration.

3. Quintinia (2 sp.). This genus has winged seeds facilitating migration.

4. Olearia (20 sp.). Seeds with pappus.

5. Craspedia (2 sp.). Seeds with pappus. Alpine; identical with Australian species, and therefore of comparatively recent introduction.

6. Celmisia (25 sp.). Seeds with pappus. Only three Australian species, two of which are identical with New Zealand forms, probably therefore derived from New Zealand.

7. Ozothamnus (5 sp.). Seeds with pappus.

8. Epacris (4 sp.). Minute seeds. Some species are sub-tropical, and they are all found in the northern (warmer) island of New Zealand.

9. Archeria (2 sp.). Minute seeds. A species common to E. Australia and New Zealand.

10. Logania (3 sp.). Small seeds. Alpine plants.

11. Hedycarya (1 sp.).

12. Chiloglottis (1 sp.). Minute seeds. In Auckland Islands; alpine in Australia.

13. Prasophyllum (1 sp.). Minute seeds. Identical with Australian species, indicating recent transmission.

14. Orthoceras (1 sp.). Minute seeds. Identical with an Australian species.

15. Alepyrum (1 sp.). Alpine, moss-like. An Antarctic type.

16. Dichelachne (3 sp.). Identical with Australian species. An awned grass.

We thus see that there are special features in most of these plants that would facilitate transmission across the sea between temperate Australia and New Zealand, or to both from some Antarctic island; and the fact that in several of them the species are absolutely identical shows that such transmission has occurred in geologically recent times.

Species Common to New Zealand and Australia Mostly Temperate Forms.—Let us now take the species which are common to New Zealand and Australia, but found nowhere else, and which must therefore have passed from one country to the other at a more recent period than the mass of genera with which we have hitherto been dealing. These are ninety-six in number, and they present a striking contrast to the similarly restricted genera in being wholly temperate in character, the entire list presenting only a single species which is confined to sub-tropical East Australia—a grass (Apera arundinacea) only found in a few localities on the New Zealand coast.

Now it is clear that the larger portion, if not the whole, of these plants must have reached New Zealand from Australia (or in a few cases Australia from New Zealand), by transmission across the sea, because we know there has been no actual land connection during the Tertiary period, as proved by the absence of all the Australian mammalia, and almost all the most characteristic Australian birds, insects, and plants. The form of the sea-bed shows that the distance could not have been less than 600 miles, even during the greatest extension of Southern New Zealand and Tasmania; and we have no reason to suppose it to have been less, because in other cases an equally abundant flora of identical species has reached islands at a still greater distance—notably in the case of the Azores and Bermuda. The character of the plants is also just what we should expect: for about two-thirds of them belong to genera of world-wide range in the temperate zones, such as Ranunculus, Drosera, Epilobium, Gnaphalium, Senecio, Convolvulus, Atriplex, Luzula, and many sedges and grasses, whose exceptionally wide distribution shows that they possess exceptional powers of dispersal and vigour of constitution, enabling them not only to reach distant countries, but also to establish themselves there. Another set of plants belong to especially Antarctic or south temperate groups, such as Colobanthus, Acæna, Gaultheria, Pernettya, and Muhlenbeckia, and these may in some cases have reached both Australia and New Zealand from some now submerged Antarctic island. Again, about one-fourth of the whole are alpine plants, and these possess two advantages as colonisers. Their lofty stations place them in the best position to have their seeds carried away by winds; and they would in this case reach a country which, having derived the earlier portion of its flora from the side of the tropics, would be likely to have its higher mountains and favourable alpine stations to a great extent unoccupied, or occupied by plants unable to compete with specially adapted alpine groups.

Fully one-third of the exclusively Australo-New Zealand species belong to the two great orders of the sedges and the grasses; and there can be no doubt that these have great facilities for dispersion in a variety of ways. Their seeds, often enveloped in chaffy glumes, would be carried long distances by storms of wind, and even if finally dropped into the sea would have so much less distance to reach the land by means of surface currents; and Mr. Darwin's experiments show that even cultivated oats germinated after 100 days' immersion in sea-water. Others have hispid awns by which they would become attached to the feathers of birds, and there is no doubt this is an effective mode of dispersal. But a still more important point is, probably, that these plants are generally, if not always, wind-fertilised, and are thus independent of any peculiar insects, which might be wanting in the new country.

Why Easily-Dispersed Plants have often Restricted Ranges.—This last consideration throws light on a very curious point, which has been noted as a difficulty by Sir Joseph Hooker, that plants which have most clear and decided powers of dispersal by wind or other means, have not generally the widest specific range; and he instances the small number of Compositæ common to New Zealand and Australia. But in all these cases it will, I think, be found that although the species have not a wide range the genera often have. In New Zealand, for instance, the Compositæ are very abundant, there being no less than 167 species, almost all belonging to Australian genera, yet only about one-sixteenth of the whole are identical in the two countries. The explanation of this is not difficult. Owing to their great powers of dispersal, the Australian Compositæ reached New Zealand at a very remote epoch, and such as were adapted to the climate and the means of fertilisation established themselves; but being highly organised plants with great flexibility of organisation, they soon became modified in accordance with the new conditions, producing many special forms in different localities; and these, spreading widely, soon took possession of all suitable stations. Henceforth immigrants from Australia had to compete with these indigenous and well-established plants, and only in a few cases were able to obtain a footing; whence it arises that we have many Australian types, but few Australian species, in New Zealand, and both phenomena are directly traceable to the combination of great powers of dispersal with a high degree of adaptability. Exactly the same thing occurs with the still more highly specialised Orchideæ. These are not proportionally so numerous in New Zealand (thirty-eight species), and this is no doubt due to the fact that so many of them require insect-fertilisation often by a particular family or genus (whereas almost any insect will fertilise Compositæ), and insects of all orders are remarkably scarce in New Zealand.188 This would at once prevent the establishment of many of the orchids which may have reached the islands, while those which did find suitable fertilisers and other favourable conditions would soon become modified into new species. It is thus quite intelligible why only three species of orchids are identical in Australia and New Zealand, although their minute and abundant seeds must be dispersed by the wind almost as readily as the spores of ferns.

Another specialised group—the Scrophularineæ—abounds in New Zealand, where there are sixty-two species; but though almost all the genera are Australian only three species are so. Here, too, the seeds are usually very small, and the powers of dispersal great, as shown by several European genera—Veronica, Euphrasia, and Limosella, being found in the southern hemisphere.

Looking at the whole series of these Australo-New Zealand plants, we find the most highly specialised groups—Compositæ, Scrophularineæ, Orchideæ—with a small proportion of identical species (one-thirteenth to one twentieth), the less highly specialised—Ranunculaceæ, Onagrariæ and Ericeæ—with a higher proportion (one-ninth to one-sixth), and the least specialised—Junceæ, Cyperaceæ and Gramineæ—with the high proportion in each case of one-fourth. These nine are the most important New Zealand orders which contain species common to that country and Australia and confined to them; and the marked correspondence they show between high specialisation and want of specific identity, while the generic identity is in all cases approximately equal, points to the conclusion that the means of diffusion are, in almost all plants ample, when long periods of time are concerned, and that diversities in this respect are not so important in determining the peculiar character of a derived flora, as adaptability to varied conditions, great powers of multiplication, and inherent vigour of constitution. This point will have to be more fully discussed in treating of the origin of the Antarctic and north temperate members of the New Zealand flora.

Summary and Conclusion on the New Zealand Flora.—Confining ourselves strictly to the direct relations between the plants of New Zealand and of Australia, as I have done in the preceding discussion, I think I may claim to have shown that the union between the two countries in the latter part of the Secondary epoch at a time when Eastern Australia was widely separated from Western Australia (as shown by its geological formation and by the contour of the sea-bottom) does sufficiently account for all the main features of the New Zealand flora. It shows why the basis of the flora is fundamentally Australian both as regards orders and genera, for it was due either to a direct land connection or a somewhat close approximation between the two countries. It shows also why the great mass of typical Australian forms are unrepresented, for the Australian flora is typically western and temperate, and New Zealand received its immigrants from the eastern island which had itself received only a fragment of this flora, and from the tropical end of this island, and thus could only receive such forms as were not exclusively temperate in character. It shows, further, why New Zealand contains such a very large proportion of tropical forms, for we see that it derived the main portion of its flora directly from the tropics. Again, this hypothesis shows us why, though the specially Australian genera in New Zealand are largely tropical or sub-tropical, the specially Australian species are wholly temperate or alpine; for these are comparatively recent arrivals, they must have migrated across the sea in the temperate zone, and these temperate and alpine forms are exactly such as would be best able to establish themselves in a country already stocked mainly by tropical forms and their modified descendants. This hypothesis further fulfils the conditions implied in Sir Joseph Hooker's anticipation that—"these great differences (of the floras) will present the least difficulties to whatever theory may explain the whole case,"—for it shows that these differences are directly due to the history and development of the Australian flora itself, while the resemblances depend upon the most certain cause of all such broad resemblances—close proximity or actual land connection.

One objection will undoubtedly be made to the above theory,—that it does not explain why some species of the prominent Australian genera Acacia, Eucalyptus, Melaleuca, Grevillea, &c., have not reached New Zealand in recent times along with the other temperate forms that have established themselves. But it is doubtful whether any detailed explanation of such a negative fact is possible, while general explanations sufficient to cover it are not wanting. Nothing is more certain than that numerous plants never run wild and establish themselves in countries where they nevertheless grow freely if cultivated; and the explanation of this fact given by Mr. Darwin—that they are prevented doing so by the competition of better adapted forms—is held to be sufficient. In this particular case, however, we have some very remarkable evidence of the fact of their non-adaptation. The intercourse between New Zealand and Europe has been the means of introducing a host of common European plants,—more than 150 in number, as enumerated at the end of the second volume of the Handbook; yet, although the intercourse with Australia has probably been greater, only two or three Australian plants have similarly established themselves. More remarkable still, Sir Joseph Hooker states: "I am informed that the late Mr. Bidwell habitually scattered Australian seeds during his extensive travels in New Zealand." We may be pretty sure that seeds of such excessively common and characteristic groups as Acacia and Eucalyptus would be among those so scattered, yet we have no record of any plants of these or other peculiar Australian genera ever having been found wild, still less of their having spread and taken possession of the soil in the way that many European plants have done. We are, then, entitled to conclude that the plants above referred to have not established themselves in New Zealand (although their seeds may have reached it) because they could not successfully compete with the indigenous flora which was already well established and better adapted to the conditions of climate and of the organic environment. This explanation is so perfectly in accordance with a large body of well-known facts, including that which is known to every one—how few of our oldest and hardiest garden plants ever run wild—that the objection above stated will, I feel convinced, have no real weight with any naturalists who have paid attention to this class of questions.

CHAPTER XXIII

ON THE ARCTIC ELEMENT IN SOUTH TEMPERATE FLORAS

European Species and Genera of Plants in the Southern Hemisphere—Aggressive Power of the Scandinavian Flora—Means by which Plants have Migrated from North to South—Newly moved Soil as Affording Temporary Stations to Migrating Plants—Elevation and Depression of the Snow-line as Aiding the Migration of Plants—Changes of Climate Favourable to Migration—The Migration from North to South has been long going on—Geological Changes as Aiding Migration—Proofs of Migration by way of the Andes—Proofs of Migration by way of the Himalayas and Southern Asia—Proofs of Migration by way of the African Highlands—Supposed Connection of South Africa and Australia—The Endemic Genera of Plants in New Zealand—The Absence of Southern Types from the Northern Hemisphere—Concluding Remarks on the New Zealand and South Temperate Floras.

We have now to deal with another portion of the New Zealand flora which presents perhaps equal difficulties—that which appears to have been derived from remote parts of the north and south temperate zones; and this will lead us to inquire into the origin of the northern or Arctic element in all the south temperate floras.

More than one-third of the entire number of New Zealand genera (115) are found also in Europe, and even fifty-eight species are identical in these remote parts of the world. Temperate South America has seventy-four genera in common with New Zealand, and there are even eleven species identical in the two countries, as well as thirty-two which are close allies or representative species. A considerable number of these northern or Antarctic plants and many more which are representative species, are found also in Tasmania and in the mountains of temperate Australia; and Sir Joseph Hooker gives a list of thirty-eight species very characteristic of Europe and Northern Asia, but almost or quite unknown in the warmer regions, which yet reappear in temperate Australia. Other genera seem altogether Antarctic—that is, confined to the extreme southern lands and islands; and these often have representative species in Southern America, Tasmania, and New Zealand, while others occur only in one or two of these areas. Many north temperate genera also occur in the mountains of South Africa. On the other hand, few if any of the peculiar Australian or Antarctic types have spread northwards, except some of the former which have reached the mountains of Borneo, and a few of the latter which spread along the Andes to Mexico.

On these remarkable facts, of which I have given but the barest outline, Sir Joseph Hooker makes the following suggestive observations:—

"When I take a comprehensive view of the vegetation of the Old World, I am struck with the appearance it presents of there being a continuous current of vegetation (if I may so fancifully express myself) from Scandinavia to Tasmania; along, in short, the whole extent of that arc of the terrestrial sphere which presents the greatest continuity of land. In the first place Scandinavian genera, and even species, reappear everywhere from Lapland and Iceland to the tops of the Tasmanian Alps, in rapidly diminishing numbers it is true, but in vigorous development throughout. They abound on the Alps and Pyrenees, pass on to the Caucasus and Himalayas, thence they extend along the Khasia Mountains, and those of the peninsulas of India to those of Ceylon and the Malayan Archipelago (Java and Borneo), and after a hiatus of 30° they appear on the Alps of New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania, and beyond these again on those of New Zealand and the Antarctic Islands, many of the species remaining unchanged throughout! It matters not what the vegetation of the bases and flanks of these mountains may be; the northern species may be associated with alpine forms of Germanic, Siberian, Oriental, Chinese, American, Malayan, and finally Australian, and Antarctic types; but whereas these are all, more or less, local assemblages, the Scandinavian asserts his prerogative of ubiquity from Britain to beyond its antipodes."189