Полная версия

Полная версияBasque Legends; With an Essay on the Basque Language

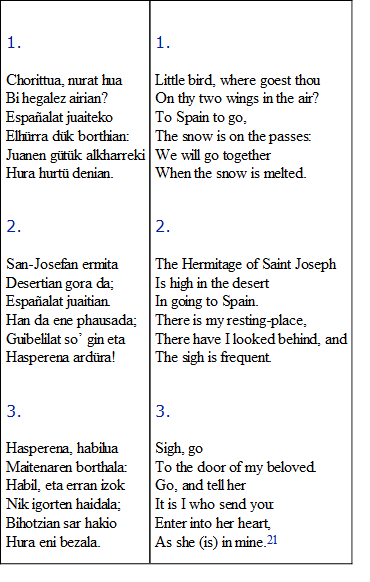

[21] This song is prettily translated in Miss Costello’s “Béarn and the Pyrénées,” London, 1844, where are also translations of some other Basque songs, the originals of which I have failed to trace.

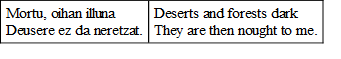

The songs of the Agots, or Cagots, those Pariahs of the Pyrénées, who dwelt apart shunned and despised by all, are, as might be expected, uniformly sad. The misery of the labourer’s lot, and even of that of the contrabandista, is more frequently dwelt upon than the compensations to the poverty of the one, or the transient gleams of good fortune of the other. At least, such is the case in all those which are really songs of the people. In these there are not many delights of “life under the greenwood tree,” as in Robin Hood, or our factitious gipsies’ songs. The forest is an object of dread to the Basque poet, and it requires courage and all the powerful attraction of a loved one to induce him to traverse by night its gloomy shades; but then—

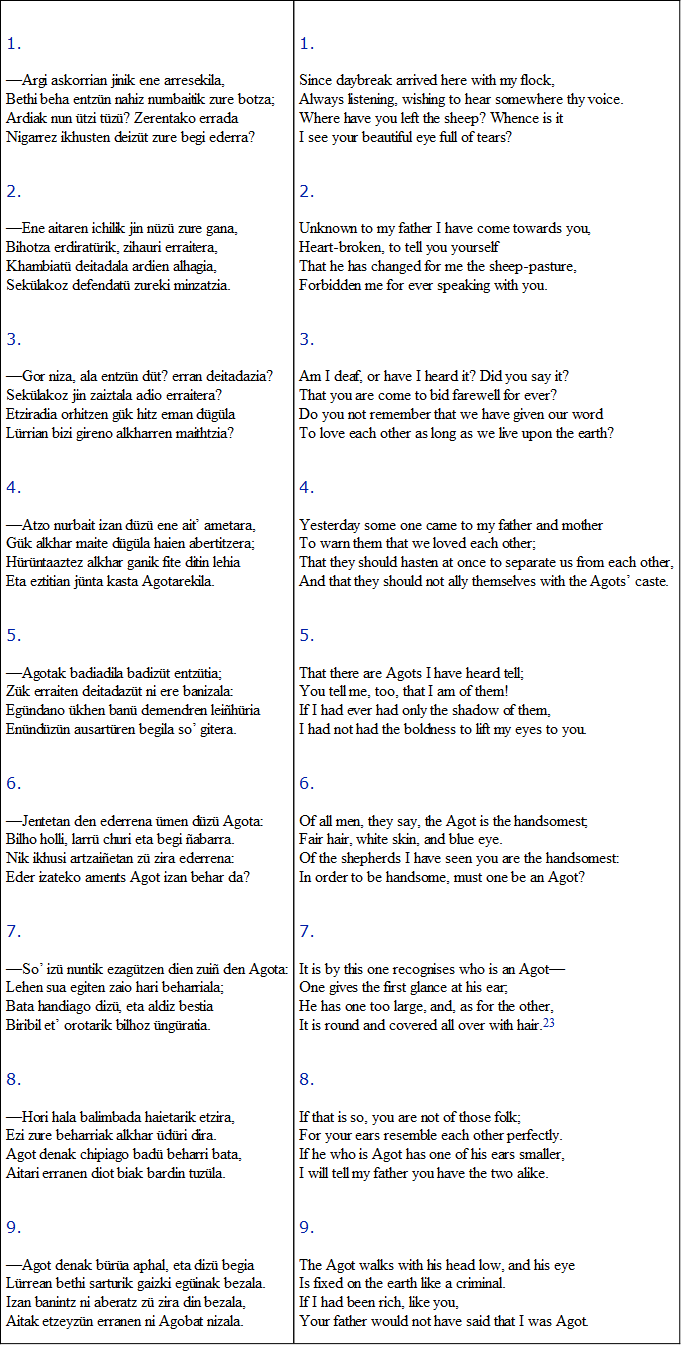

The following is an illustration of the Cagots’ or Agots’ songs. This piece, of which the author was the hero, was written about 1783, when he was eighteen years old. Cf. Fr. Michel, “Les Races Maudites de France et de l’Espagne,” vol. ii. p. 150, and “Le Pays Basque,” p. 270; and, for the music, Sallaberry, “Chants Populaires du Pays Basque,” p. 172.201

[23] More often the Cagots’ ears were said to be either completely round or with very long lobes, or with the lobes adhering. We have found examples of all of these in the Basque country, but not confined or peculiar to the Cagots. A case like that described in the verse above we have never seen.

There are, too, verses of grim and bitter humour, which tell better than the pen of the historian how wretched was formerly the lot of the peasant, even in this favoured corner of France. Famine is personified, and has a name given it, drawn in biting irony from that of the highest Saint of the Church Calendar, Petiri Sanz (S. Peter). He wanders round the country seeking where to settle permanently; at one place he is driven off by (the sale of) rosin, at another little maize, at another by cheese and cherries; but at last he fixes his abode definitively at St. Pée (another form of Peter), on the Nivelle, where they have nothing at all to sell, and where he torments the inhabitants by forcing them to keep many a fast beyond those of ecclesiastical obligation. The same strain of gloomy humour appears in another form in a poem entitled “Mes Méditations,”202 in which a young priest of Ciboure, slowly dying of consumption, traces in detail all the physical and mental agonies of his approaching dissolution. A much less grim example, however, is contained in the following, which we quote mainly because of its brevity. It may remind some of our readers of a longer but similar strain which used often to be sung at harvest-homes in the Midland Counties:—

[25] Michel, “Le Pays Basque,” p. 414.

More literally:—

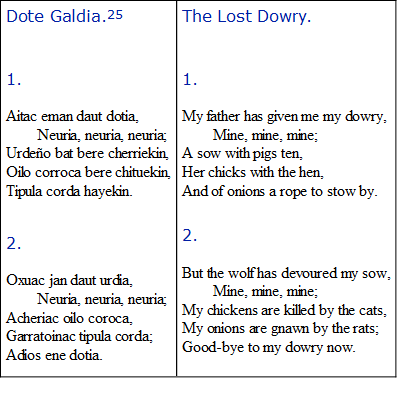

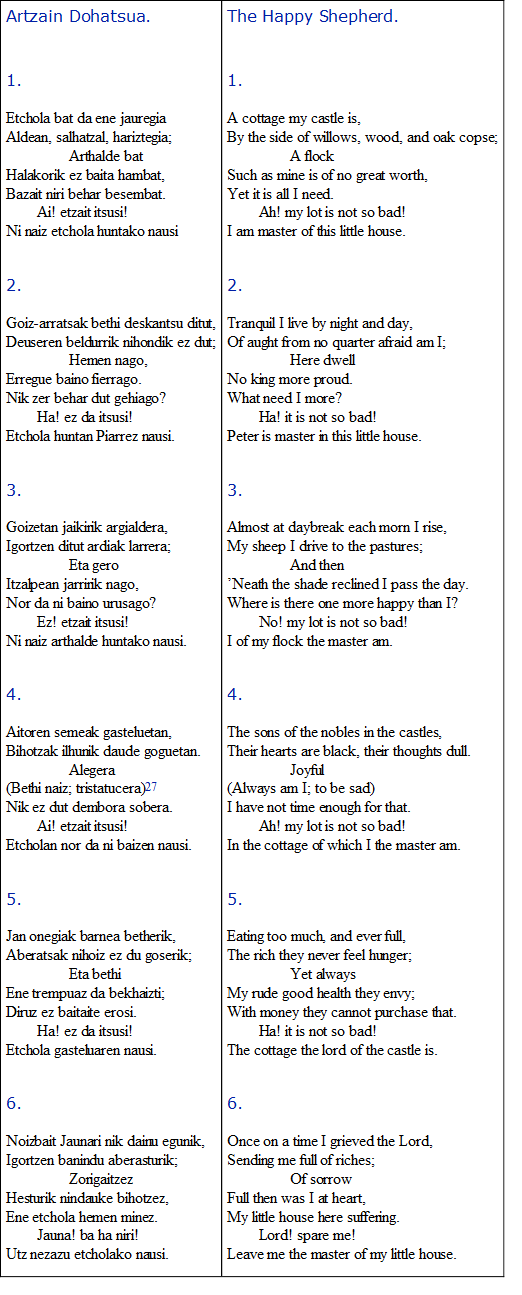

1My father has given me the dowry,Mine, mine, mine;A sow with her little pigs,A brood hen with her chickens,A cord of onions with them.2The wolf has eaten my sow,Mine, mine, mine;The fox my brood hen,The rats my cord of onions,Good-bye, my dowry.The lack of good poetry in Basque is certainly not due to want of encouragement. Moreover, the wish to produce it is there, but the power seems lacking. For over twenty years prizes have been annually given, first at Urrugne, and then at Sare, by M. Antoine d’Abbadie, of Abbadia. But among the multitude of competing poems few have been of any real value, and both in merit and in the number presented they seem to diminish annually. The best of them have been written by men of the professional class, whose taste has been formed on French, or Spanish, or classical, rather than on native models. The following is considered by native critics to be among the best, though several others are very little, if at all, inferior203:—

[27] A line has dropped out of the MS. here. We supply the probable meaning. The composer is one P. Mendibel, 1859.

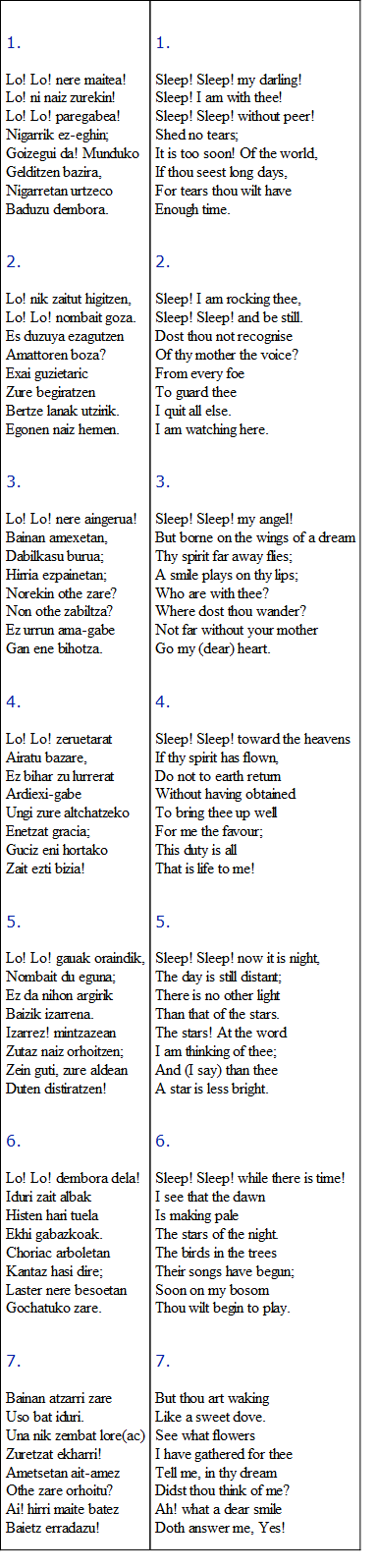

A pretty cradle song, “Lo! Lo! ene Maitea” (“Sleep! Sleep! my Darling”), by M. Larralde, a physician of St. Jean de Luz, won the prize at Urrugne in 1859. It is written to a tune composed by the Vicomte de Belzunce; the words have been printed in the “Lettres Labourdines,” par H. L. Fabre (Bayonne, 1869).

The following belongs to a more quaint and popular class of lullaby, or cradle songs; as it is so simple we do not give the Basque:—

Little Peter.213

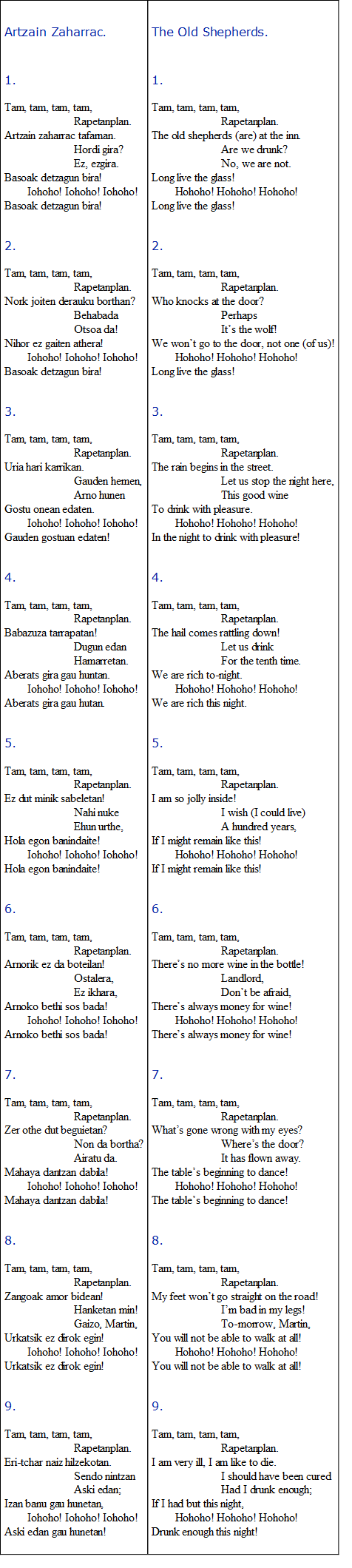

1Ah, my little Peter,I am sleepy, and—Shall I go to bed?Go on spinning, and—Then, then, then,Go on spinning, and—Then, then, yes.2Dear little Peter,I have spun, and—Shall I go to bed?Put the thread up in skeins, and—Then, then, then,Put the thread up in skeins, and—Then, then, yes.3Dear little Peter,I have put it in skeins, and—Shall I go to bed?Wind off the thread, and—Then, then, then,Wind off the thread, and—Then, then, yes.4Dear little Peter,I have wound it off, and—Shall I go to bed?Bleach it, and—Then, then, then,Bleach it, and—Then, then, yes.5Dear little Peter,I have bleached it, and—Shall I go to bed?Weave it, and—Then, then, then,Weave it, and—Then, then, yes.6Dear little Peter,I have woven it, and—Shall I go to bed?Cut it, and—Then, then, then,Cut it, and—Then, then, yes.7Dear little Peter,I have cut it, and—Shall I go to bed?Sew it, and—Then, then, then,Sew it, and—Then, then, yes.8Oh! my little Peter,I have sewn it, and—Shall I go to bed?It is daylight! and—Then, then, then,It is daylight! and—Then, then, yes!The best living Basque poets are—on the French side, Captain Elisamboure, of Hendaye; and Iparraguirre, of San Sebastian, among the Spanish Basques. Iparraguirre is now very old. He is the author of the song “Guernicaco Arbola” (“The Tree of Guernica,” in Biscay), an oak under which the Lords of Biscay swore fidelity to the Fueros. This has become almost the national song of the Basques.214 A few words on two other classes of songs, the drinking and the macaronic, must conclude our remarks. The most spirited drinking song is the following.215 It must be remembered, in excuse, that the shepherds live a very hard life on the mountains the greater part of the year, and taste little wine there.

It is not at all uncommon in a country where, within the space of some twenty miles, the traveller may hear at least four languages—French, Gascoun, Basque, and Spanish—to find two or more of these mixed in the same poem, and sometimes with a little Latin as well. This occurs frequently in the noëls, where the angel speaks in French or Latin, and the shepherds reply in Gascoun or Basque; also sometimes in the love songs, where the French or Spanish lover will try to soften the heart of a Basque maiden by compliments in French or Spanish, while she greatest tour de force of this kind we know, both as to language and rhyme, is the song given in Fr. Michel’s “Le Pays Basque,” p. 429. We quote the first verse only; but the song continues with twenty-eight successive Basque rhymes in “in,” and the last seven in “en.”

Almost every one of these Basque songs, like all true lyrics, has been adapted to some tune, either older than the words, or composed specially by the author. The music is often superior to the words. In the Nineteenth Century for August, 1878, Grant-Duff speaks of some of the Basque airs sung by the Béarnais tenor, Pascal Lamazou, as “extraordinarily beautiful.”216 Lamazou died at Pau in May, 1878. His répertoire consisted of fifty Pyrenean songs, of which thirty-four are Béarnais, fourteen Basque, and two are from the “Pyrénées Orientales.”217 One of the Basque airs “Artzaina,” has somehow got attached to the popular American hymn, “I want to be an angel.” Another, and larger collection, including more correct renderings of some of Lamazou’s fourteen, is that of Sallaberry, “Chants Populaires du Pays Basque” (Bayonne, 1870). But, long before this, a collection of Basque Songs, Zorzicos, and dance music was published in San Sebastian, by J. D. Iztueta, in 1824 and 1826. Excellent reviews of these two works, with translations of some of the words, appeared in the Foreign Review and Continental Miscellany, vol. ii., pp. 338, 1828; and in vol. iv., p. 198. Some specimens of music are to be found at the end of Michel’s “Le Pays Basque,” in the “Cancionero Vasco”—now in course of publication, and so often referred to—and in other local publications, besides those in private hands. Basquophiles love to narrate that Rossini passed a summer in the Basque village of Cambo, and believe that they can recognise the influence of Basque airs in some of his subsequent operas. However this may be, let no one judge of Basque music by the noëls usually howled in the streets at Christmas and the New Year, or by the doleful productions of the last Carlist War. It would be equally fair to judge of English music by the serenades of the waits at Christmas. We refer those who wish to investigate further the subject of this chapter to the excellent work, “Le Pays Basque,” par M. Fr. Michel (Paris and London, 1857), for the French, to the “Cancionero Vasco,” by Don José Manterola, now in course of publication at San Sebastian, for the Spanish, Basque; and to M. Sallaberry’s “Chants Populaires du Pays Basque” for the music.

1Borne on thy wings amidst the air,Sweet bird, where wilt thou go?For if thou wouldst to Spain repair,The ports are filled with snow.Wait, and we will fly together,When the Spring brings sunny weather.2St. Joseph’s Hermitage is lone,Amidst the desert bare,And when we on our way are gone,Awhile we’ll rest us there;As we pursue our mountain track,Shall we not sigh as we look back?3Go to my love, oh! gentle sigh,And near her chamber hover nigh;Glide to her heart, make that thy shrine,As she is fondly kept in mine.Then thou may’st tell her it is IWho sent thee to her, gentle sigh!1

See on this head M. Vinson’s Essay in Appendix.

2

The second part of M. Cerquand’s “Légendes et Récits Populaires du Pays Basque” (Pau, 1876), appeared while the present work was passing through the press. It is chiefly occupied with legends of Basa-Jaun and Lamiñak.

3

Not that we suppose all these tales to be atmospheric myths; we adopt this only as the provisional hypothesis which appears at present to cover the largest amount of facts. It seems certainly to be a “vera causa” in some cases; but still it is only one of several possible “veræ causæ,” and is not to be applied to all.

4

Cf. Campbell’s “Introduction,” p. xxviii.:—“I have never heard a story whose point was obscenity publickly told in a Highland cottage; and I believe such are rare. If there was an occasional coarse word spoken, it was not coarsely meant.”

5

One class, of which we have given no example, is that of the Star Legend given by M. Cerquand, “Légendes et Récits Populaires du Pays Basque,” p. 19, and reprinted, with variations, by M. Vinson, “Revue de Linguistique,” Tom. VIII., 241–5, January, 1876.

6

Cf. “Etudes Historiques sur la Ville de Bayonne, par MM. Balasque et Dulaurens,” Vol. I., p. 49.

7

We have purposely omitted references to Greek and Latin mythology, as these are to be found “passim” in the pages of Max Müller and of Cox. The preparation for the Press was made at a distance from our own library, or more references to Spanish and patois sources would have been given.

8

See page 192.

9

There seems to be a Basque root “Tar,” which appears in the words, “Tarro, Tarrotu, v., devenir un peu grand. Tarrapataka, adv., marchant avec précipitation et en faisant du bruit.”—Salaberry’s “Vocabulaire Bas-Navarrais,” sub voce. Cf. Campbell’s “Tales of the Western Highlands,” Vol. II., 94:—“He heard a great Tartar noise,” Tartar being printed as if it were a Gaelic word.

10

Cf. also Müller’s “Fragmenta Historicorum Græcorum” (Didot, Paris, 1841), Vol. I., p. 246. “Ephori Fragmenta,” 51, with the references there given.

11

Cf. also the Gaelic, “The Story and the Lay of the Great Fool,” Campbell, Vol. III., pp. 146–154.

12

This talking giant’s ring appears in Campbell’s “Popular Tales of the West Highlands,” Vol. I., p. 111, in the tale called “Conall cra Bhuidhe.” He also refers (p. 153) to Grimm’s tale of the “Robber and his Sons,” where the same ring appears:—“He puts on the gold ring which the giant gave him, which forces him to cry out, ‘Here I am!’ He bites off his own finger, and so escapes.”

13

Cf. Campbell’s “Mac-a-Rusgaich,” Vol. II., 305:—“I am putting it into the covenant that if either one of us takes the rue, that a thong shall be taken out of his skin, from the back of his head to his heel.”

14

Salamanca was the reputed home of witchcraft and devilry in De Lancre’s time (1610). He is constantly punning on the word. It is because “Sel y manque,” etc. See also the story of Gerbert, Pope Sylvester II., in the 10th century.

15

This incident is found in Cenac-Moncaut’s Gascon tale, “Le Coffret de la Princesse.” “Litterature Populaire de la Gascogne,” p. 193 (Dentu, Paris, 1868).

16

For this incident compare the death of the giant in one of the versions of “Jack the Giant-Killer;” and especially “the Erse version of Jack the Giant-Killer.” Campbell, Vol. II., p. 327.

17

This agreement is found also in the Norse and in Brittany. See “Contes Populaires de la Grande Bretagne,” by Loys Brueyre, pp. 25, 26. This is an excellent work. The incident of Shylock, in the “Merchant of Venice,” will occur to every one.

18

Literally, “Marsh of the Basa-Andre.” The “Puits des Fées” are common in France, especially in the Landes and in the Gironde.

19

Only in this, and one other tale, is the word “prince” used instead of “king’s son.” Compare the Gaelic of Campbell in this respect. This tale is probably from the French, and the Tartaro is only a giant.

20

One of the oddest instances of mistaken metaphors that we know of occurs in “La Vie de St. Savin, par J. Abbadie, Curé de la Paroisse” (Tarbes, 1861). We translate from the Latin, which is given in a note:—“Intoxicated with divine love, he was keeping vigil according to his custom, and when he could not find a light elsewhere, he gave light to his eyes from the light that was in his breast. The small piece of wax-taper thus lit passed the whole night till morning without being extinguished.”—Off. S. Savin.

21

This Fleur-de-lis was supposed by our narrator to be some mark tattooed or impressed upon the breast of all kings’ sons.

22

This, of course, is “Little George,” and makes one suspect that the whole tale is borrowed from the French; though it is just possible that only the names, and some of the incidents, may be.

23

Cf. “Ezkabi Fidel,” 112, below.

24

In Campbell’s “Tale of the Sea-Maiden,” instead of looking in his ear, the king’s daughter put one of her earrings in his ear, the last two days, in order to wake him; and it is by these earrings and her ring that she recognises him afterwards, instead of by the pieces of dress and the serpent’s tongues.

25

Campbell, Vol. I., lxxxvii., 8, has some most valuable remarks on the Keltic Legends, showing the Kelts to be a horse-loving, and not a seafaring race—a race of hunters and herdsmen, not of sailors. The contrary is the case with these Basque tales. The reader will observe that the ships do nothing extraordinary, while the horses behave as no horse ever did. It is vice versâ in the Gaelic Tales, even when the legends are identical in many particulars.

26

The three days’ fight, and the dog, appear in Campbell’s “Tale of the Sea-Maiden,” Vol. I., pp. 77–79.

27

The Basque word usually means “Eau de Cologne.”

28

This is a much better game than the ordinary one of tilting at a ring with a lance, and is a much more severe test of horsemanship. The ring, an ordinary lady’s ring, is suspended by a thread from a cross-bar, at such a height that a man can just reach it by standing in his stirrups. Whoever, starting from a given point, can put a porcupine’s quill, or a small reed, through the ring, and thus carry it off at a hand-gallop, becomes possessor of the ring. We have seen this game played at Monte Video, in South America; and even the Gauchos considered it a test of good horsemanship. Formerly, it seems, the ring was suspended from the tongue of a bell, which would be set ringing when the ring was carried away. The sword, of course, was the finest rapier.

29

One of those present here interrupted the reciter—“What did she hit the serpent on the tail for?” “Why, to kill him, of course,” was the reply; “ask Mr. Webster if serpents are not killed by hitting them on the tail?”

30

I have a dim recollection of having read something very similar to this either in a Slavonic or a Dalmatian tale.

31

This incident is in the translation of a tale by Chambers, called “Rouge Etin,” in Brueyre’s “Contes de la Grande Bretagne,” p. 64. See notes ad loc.

32

In the Pyrénées the ewes are usually milked, and either “caillé”—a kind of clotted cream—or cheese is made of the milk. The sheep for milking are often put in a stable, or fold, for the night.

33

For the “fairies’ holes,” see Introduction to the “Tales of the Lamiñak,” p. 48.

34

Cf. “Mahistruba,” p. 100; and “Beauty and the Beast,” p. 167.

35

Silk kerchiefs are generally used, especially by women, as head-dresses, and not as pocket-handkerchiefs, all through the south of France.

36

“Légendes et Récits Populaires du Pays Basque,” par M. Cerquand. Part I., Pau, 1875, and Part II., p.28, Pau, 1876.

37

Cf. Campbell’s tale, “The Keg of Butter,” Vol. III., 98, where the fox cheats the wolf by giving him the bottoms of the oats and the tops of the potatoes. See also the references there given.

38

Cf. Cerquand, Part I., p. 27, “Ancho et les Vaches,” and notes. Also Part II., 34, et seq.

39

Cf. Cerquand, Part I., pp. 33, 34, “La Dame au Peigne d’Or.”

40

Cerquand, Part I., p. 30, “Basa-Jauna et le Salve Regina.”

41

Cerquand, “L’Eglise d’Espés.” “Le Pont de Licq,” Part I., pp. 31, 32, and Part II., pp. 50–52.

42

But compare the well or marsh of the Basa-Andre in the Tartaro tale, p. 15.

43

Cerquand, Part I., pp. 32, 33.

44

The owner of the farm and the “métayère,” or tenant’s wife. Under the “métayer” system the landlord and tenant divide the produce of the farm. This is the case almost universally in South-Western France, as elsewhere in the South. The “métayer’s” residence often adjoins the landlord’s house.

45

Cf. “The Sister and her Seven Brothers.”

46

This is the only representation that we know of Basa-Jaun as a vampire.

47

As the Basques commonly go barefooted, or use only hempen sandals, the feet require to be washed every evening. This is generally done before the kitchen fire, and in strict order of age and rank. Cf. also “The Sister and her Seven Brothers.”

48

The running water, we suspect, gives the girl power over the witch.

49

“Hazel sticks.” In the sixteenth century the dog-wood, “cornus sanguinea,” seems to have been the witches’ wood. In the “Pastorales,” all the enchantments, etc., are done by the ribboned wands of the Satans. This tale ends rather abruptly. The reciter grew very tired at the last.

50

Basque Lamiñak always say exactly the contrary to what they mean.

51

Cf. Bladé’s “Contes Agenais,” “Les Deux Filles,” and Köhler’s “Notes Comparatives” on the tale, p. 149.

52

That is, the wife span evenly with a clear steady sound of the wheel, but the man did it unevenly.

53

Cf. Campbell’s “The Brollachan,” Vol. II., p. 189, with the notes and variations. “Me myself,” as here, seems the equivalent of the Homeric “οὔτις.”

54

M. Cerquand has the same tale, Part I., p. 41.

55

This is a very widely spread legend. Cf. Patrañas, “What Ana saw in the Sunbeam;” “Duffy and the Devil,” in Hunt’s “Popular Romances of the West of England,” p. 239; also Kennedy’s “Idle Girl and her Aunts,” which is very close to the Spanish story; and compare the references subjoined to the translation of the Irish legend in Brueyre’s “Contes Populaires de la Grande Bretagne,” p. 159.

56

Cf. “The Brewery of Egg-shells,” in Croker’s “Fairy Legends of the South of Ireland,” pp. 32–36.

57

This tale, or at least this version of it, with the names Rose and Bellarose, must come from the French.

58

“A little dog” is mentioned in Campbell’s “The Daughter of the Skies,” Vol. I., 202, and notes.

59

”Kopetaen erdian diamanteko bista batez”—“a view of diamonds in the middle of the forehead.”

60

Nothing has been said about this dress before. Something must have dropped out of the story.

61

At a Pyrenean wedding the bride and bridegroom, with the wedding party, spend nearly the whole day in promenading through the town or village. The feast often lasts several days, and the poor bride is an object of pity, she sometimes looks so deadly tired.

62

Cerquand, Part I., p. 29, notes to Conte 8; Fr. Michel, “Le Pays Basque,” p. 152 (Didot, Paris, 1857).

63

“Akhelarre,” literally “goat pasture.” This was the name in the 16th century.

64

This belief in a toad sitting at the church door to swallow the Host is found in De Lancre.

65

That is, one with bran, or herbs, wood-ashes, &c., or plain water.

66

M. Cerquand gives this tale at length, Part II., pp. 10, 11. The incidents are very slightly changed.