Полная версия

Полная версияBasque Legends; With an Essay on the Basque Language

Satan and Bulgifer; Abraham and Isaac.

Satan.

Abraham, art thou ignorant?What art thou thinking of?Leave him in life;Thou hast some wise hairs.I tell thee to returnTo the house with the child;And there you shall liveWith very great joy.Abraham.

Ah! alas! wretched torment!Always thus on this earthSatan doth vex meIn all my doings.Nevertheless, I take courage;Yes, even nowTo slay IsaacI am ready on the instant.He has given me the order,The good God Himself,That I sacrifice IsaacOn this mountain myself.Bulgifer.

He who gave you this orderWas not God. No!Go off to your house,And take your young son.Abraham.

My only son Isaac,If I sacrifice him,All of my raceI quickly destroy.The good God had told meThat he would marry;But if he dies now,How can that be?I trust, nevertheless,On our Lord God;I am willing to offer to Him,To Him alone, my son.At last Satan and Bulgifer go off, exclaiming:—

O, you accursed one!You always overcome us;To confusion alwaysYou do put us.But, if we no more tempt you,We will tempt some one else;And we will even take downTo hell some soul.In despair we departFor ever from thee;And we leave you nowIn a very sad case.After a few words between father and son, Isaac then offers himself, and prays as follows:—

People, I pray you, lookOn this poor innocent child;I am about to leave the world,And have done harm to none. (Music.)O Lord! our Saviour!Unjustly crucified!Lord, I must alsoSoon leave this world. (Music.)O King of Heaven!Who art powerfulAbove all other,Wise and triumphant. (Music.)I ask pardon of TheeFor all my sins,Wherewith I oft have offendedThee from my birth.He binds himself, and goes on:—

All those, O Lord!Blot from remembrance;To Thy glory, I pray,Receive me immediately.King of the Angels,Prince of the Heaven,May’st Thou grant me,I pray Thee, Thy rest.I ask Thee pardonFrom my whole heart;Succour me, O Lord!With Thy holy hand.I have not enough witTo thank Thee therewith;But if to Heaven I should go,There will I praise Thee.O Lord! I pray Thee, have pity!Thou shouldest grant it me;For to leave this worldI am determined.Angel of the Lord,Grant me strength,Since Thou artMy Guide!Lord, I commendTo Thee my spirit;It is Thou Who firstHast created me.And O! great God! I pray,If it be Thy will,In the repose of the blessedPlace my soul.Father,—whenever You will,—Sacrifice me now;—To find my GodI would depart.Abraham is in the act of sacrificing when the Angel Gabriel seizes him from behind, and bids him not do it, &c., &c. Any foreigner who, unless he has a most charming interpreter or interpretress, can sit out a whole Pastorale would surely deserve the first prize in the school of patience.

The other kind of dramatic performance is much more irregular, and may assume various forms according to the circumstances which give occasion to it. It may be only a wild kind of carnival procession, the Mascarade, where each gesticulates as the character he represents; or a charivari in honour (?) of a dotard’s marriage, wherein the advantages of celibacy over married life are sarcastically set forth; or it may take the form of a really witty impromptu comedy played on a tiny stage in honour of the marriage or the good fortune of the most popular persons of the village. One of the first kind is excellently described in Chaho’s “Biarritz, entre les Pyréneés et l’Océan,” vol. ii. pp. 84–121, to which we refer the reader. One of the last kind was acted at Louhossoa about 1866, on the double occasion of some marriages, and of the return of some young men from South America. There were three actors; the piece was witty and well played, and seemed to give the greatest satisfaction to the audience.

II

If we except the Pastorales, the whole of Basque poetry may be described as lyrical; either secular, as songs, or religious, as hymns and noëls. There is no epic in Basque,188 and scarcely any narrative ballads; even those chiefly are of uncertain date. A few sonnets exist, but they are almost exclusively translations or imitations of French, Spanish, or classical poems, and cannot be considered as genuine productions of the Basque muse. Some of the religious poetry may be described as didactic, but this again is mostly paraphrase or translation. All that is really native is lyrical. But even in song the Basques show no remarkable poetical merit. The extreme facility with which the language lends itself to rhyming desinence has a most injurious effect upon versification. There are not verses only, but whole poems, in which each line terminates with the same desinence. Instead of striving after that perfection of form which the change of a single word or even letter would affect injuriously, the Basques are too often satisfied with this mere rhyme. Their compositions, too, if published at all, are usually printed only on single sheets of paper, easily dispersed and soon lost. Hence the preservation of Basque poetry is entrusted mainly to the memory, and thus it happens that one scarcely meets with two copies of the same song exactly alike. If the memory fails, the missing words and rhymes are so easily supplied by others that it is not worth the effort to recall the precise expression used. And so it comes to pass that, while versification is very common among the Basques, high-class poetry is extremely rare. They have no song writers to compare with Burns or with Béranger. And if it be alleged that poets like these are rare, even among people far more numerous and more cultivated, the Basques still fall short, when measured by a much lower standard. They have no poets to rival the Gascon, Jasmin, or to compare with the Provençal or the Catalan singers at the other end of the Pyrenean chain. There is no modern Basque song which can be placed by the side of “Le Demiselle” and others of the Biarritz poet, Justin Larrebat; and among the older poets neither Dechepare nor Oyhenart is equal to the Béarnais, Despourrins. While the Jacobite songs of Scotland are among the finest productions of her lyric muse, the Carlist songs, on the contrary, though telling of an equally brave and romantic struggle, are one and all below mediocrity. But, while fully admitting this, there is yet much that is pleasing in Basque poetry. If it has no great merits, it is still free from any very gross defects. It is always true and manly, and completely free from affectation. It is seldom forced, and the singer sings just because it pleases him to do so, not to satisfy a craving vanity or to strain after the name and fame of a poet. The moral tone is almost always good. If at times, as in the drinking songs, and in some few of the amatory, the expression is free and outspoken, vice is never glossed over or covered with a false sentimentality. The Basque is never mawkish or equivocal—with him right is right, and wrong is wrong, and Basque poetry leaves no unpleasant after-taste behind.189

The only peculiarity, in a poetical sense, is the extreme fondness for, and frequent employment of, allegory. In the love songs the fair one is constantly addressed under some allegorical disguise. It is a star the lover admires, or it is the nightingale who bewails his sad lot. The loved one is a flower, or a heifer, a dove or a quail, a pomegranate or an apple, figures common to the poets of other countries; but the Basques, even the rudest of them, never confuse these metaphors, as more famous poets sometimes do—the allegory is ever consistently maintained throughout. Even in prose they are accustomed to this use of allegory, and catch up the slightest allusion to it; but to others it often renders their poetry obscure, and very difficult of successful translation. The stranger is in doubt whether a given poem is really meant only for a description of the habits of the nightingale, or whether the bird is a pseudonym for the poet or the poet’s mistress. Curiously enough, sometimes educated Basques seem to have almost as much difficulty in seizing this allegory as have foreigners. Thus, in a work now in course of publication,190 one of the most famous of these allegorical complaints is actually taken for a poetical description of the nightingale itself.

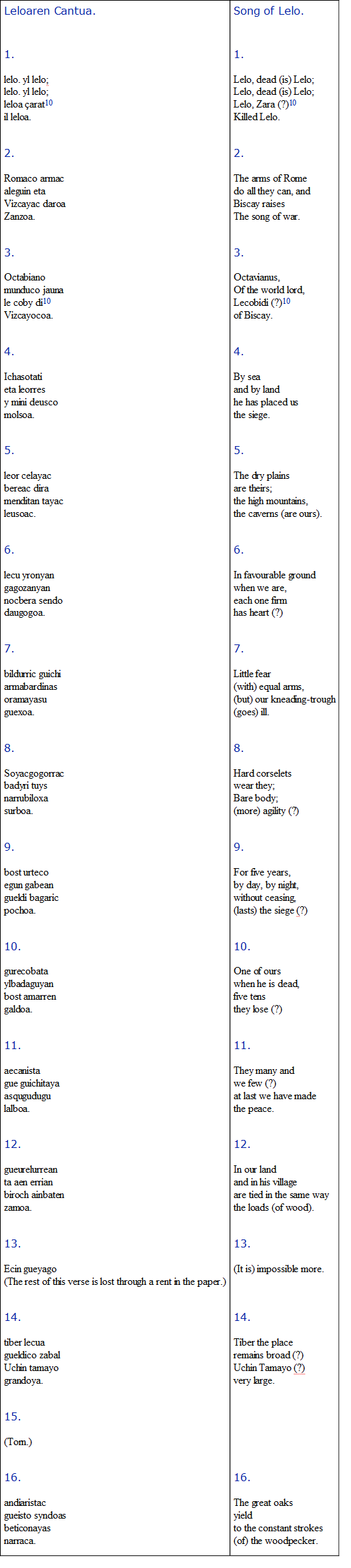

The historical songs, like all other historical remains among the Basques, are few and doubtful. There are two songs, however, for which are claimed a greater historical importance and a higher antiquity than any others can pretend to. These are the so-called “Leloaren Cantua” and the “Altabiskarco Cantua.” Both these are reputed by some writers to be almost contemporaneous with the events which they relate. The first is said to be founded on the wars of the Roman Emperor Augustus with the Cantabri; the second is an account of the defeat of Charlemagne’s rearguard at Roncesvalles, A.D. 778. The former may be some three hundred years old, but the latter is certainly a production of the nineteenth century, though none the less it is the most spirited offspring of the Basque muse. We will give the text and translation of each, and then justify our conclusions.

[10] The reader will remark that there is really no authority for treating these words as proper names. This, however, is the universal interpretation among Basques.

The history of the above song is as follows: At the close of the sixteenth century a notary of Zornoza, J. Iñiguez de Ibargüen, was commissioned by the Junta of Biscay to search the principal libraries of Spain for documents relating to the Basques. In the archives of Simancas he discovered an ancient MS. on parchment, containing verses in Basque, some almost, others wholly obliterated. Of these he copied what he could, and inserted them in p. 71 of his “Cronica general de España y sumaria de Vizcaya,” a work which still exists in manuscript in the town of Marquina. From this history of Ibargüen the song was first reproduced by the celebrated Wilhelm von Humboldt, and published by him in 1817 in a supplement to Vater’s “Mithridates.” The text above given is taken from that of the “Cancionero Vasco,” Series 2, iii., pp. 18, 20, and claims to be a new and literal copy from the MS. “Cronica” of Ibargüen. From the date of its publication by Humboldt, this piece has been the subject of much discussion. That it is one of the oldest fragments of Basque poetry hardly admits of doubt. But, when asked to believe that it is contemporary with Augustus, we must hesitate. The question arises: Did Ibargüen copy the almost defaced original exactly as it was, or did he suffer his declared predilections unconsciously to influence his reading of it?191 Many of the words are still very obscure, and the translation of them is almost guess work. The first verse has little or no apparent connection with the rest of the poem, and has given rise to the most fanciful interpretations. Lelo has been imagined by some to be the name of a Basque hero; Zara, or Zarat, who kills him, the name of another; and the two reproduce the story of Agamemnon and Ægisthus. Others, with more probability, take Lelo, as is certainly the case in other poems, for a mere refrain (the everlasting Lelo, as a Basque proverb has it) used by the singer merely to give the key to the tune or rhythm to which he modulates the rest. Chaho, with his usual audacity, would translate it “glory,” and render it thus:—

Finished is the glory! dead is the glory,

Our glory!

Old age has killed the glory,

Our glory!

But it has been very plausibly suggested192 that the verse bears a suspicious likeness to a vague reminiscence of the Moslem cry “Lâ Êlah Ulâ Allah!” &c.; and if so, this, in the north of Spain, would at one bound place the poem some eight centuries at least after the time of Augustus. The proper names have a too correct look. Octabiano, Roma, and Tiber are far too much like the Latin; for if Greeks and Romans complained, as do Strabo and Mela, of the difficulty of transcribing Basque or Iberian names into their own language, the Basques might possibly find a somewhat corresponding difficulty in transcribing Greek and Latin names into Basque. Moreover, in a later verse appears “Uchin,” a sobriquet for “Augustino,” as a baptismal name in use among the Spanish Basques to this day. What the poem really refers to we dare not assert. We present the “Leloaren Cantua” to our readers simply as one of the oldest curiosities of Basque verse, without pledging ourselves to any particular date or interpretation thereof.

Fortunately, we shall be able to speak with much more decision of the “Altabiskarco Cantua,” of which the following is the latest text:—

Altabiskarco Cantua.

1Oyhu bat aditua izan daEscualdunen mendien artetic,Eta etcheco jaunac, bere athearen aitcinean chuticIdeki tu beharriac, eta erran du: “Nor da hor? Cer nahi dautet?”Eta chacurra, bere nausiaren oinetan lo zagüena,Altchatu da, eta karrasiz Altabiscarren inguruac bethe ditu.2Ibañetaren lepoan harabotz bat aghertcen da,Urbiltcen da, arrokac ezker eta ezcuin jotcen dituelaric;Hori da urrundic heldu den armada baten burrumba.Mendien copetetaric guriec errespuesta eman diote;Beren tuten soinua adiaraci dute,Eta etcheco jaunac bere dardac zorrozten tu.3Heldu dira! heldu dira! cer lantzazco sasia!Nola cer nahi colorezco banderac heien erdian aghertcen direnCer simistac atheratcen diren heien armetaric!Cembat dira? Haurra condatzic onghi!Bat, biga, hirur, laur, bortz, sei, zazpi, zortzi, bederatzi, hamar, hameca, hamabi,Hamahirur, hamalaur, hamabortz, hamasei, hamazazpi, hemezortzi, hemeretzi, hogoi.4Hogoi eta milaca oraino!Heien condatcea demboraren galtcea liteque.Urbilditzagun gure beso zailac, errotic athera ditzagun arroca horiec,Botha ditzagun mendiaren patarra beheraHein buruen gaineraino;Leher ditzagun, herioz jo ditzagun.5Cer nahi zuten gure mendietaric Norteco guizon horiec?Certaco jin dira gure bakearen nahastera?Jaungoicoac mendiac eguin dituenean nahi izan du hec guizonec ez pasatcea.Bainan arrokac biribilcolica erortcen dira, tropac lehertcen dituzte.Odola churrutan badoa, haraghi puscac dardaran daude.Oh! cembat hezur carrascatuac! cer odolezco itsasoa!6Escapa! escapa! indar eta zaldi dituzeneac!Escapa hadi, Carlomano erreghe, hire luma beltzekin eta hire capa gorriarekin;Hire iloba maitea, Errolan zangarra, hantchet hila dago;Bere zangartasuna beretaco ez tu izan.Eta orai, Escualdunac, utz ditzagun arroca horiec,Jauts ghiten fite, igor ditzagun gure dardac escapatcen direnen contra.7Badoazi! badoazi! non da bada lantzazco sasi hura?Non dira heien erdian agheri ciren cer nahi colorezco bandera hec?Ez da gheiago simiztarik atheratcen heien arma odolez bethetaric.Cembat dira? Haurra, condatzac onghi.Hogoi, hemeretzi, hemezortzi, hamazazpi, hamasei, hamabortz, hamalaur, hamairur,Hamabi, hameca, hamar, bederatzi, zortzi, zazpi, sei, bortz, laur, hirur biga, bat.8Bat! ez da bihiric aghertcen gheiago. Akhabo da!Etcheco jauna, joaiten ahal zira zure chacurrarekin,Zure emaztearen eta zure haurren besarcatcera,Zure darden garbitcera eta alchatcera zure tutekin,Eta ghero heien gainean etzatera eta lo gitera.Gabaz, arranoac joainen dira haraghi pusca lehertu horien jatera,Eta hezur horiec oro churituco dira eternitatean.Song of Altabiscar

1A cry is heardFrom the Basque mountain’s midst.Etcheco Jauna,193 at his door erect,Listens, and cries, “What want they? Who goes there?”At his lord’s feet the dog that sleeping layStarts up, his bark fills Altabiscar194 round.2Through Ibañeta’s195 pass the noise resounds,Striking the rocks on right and left it comes;’Tis the dull murmur of a host from far,From off the mountain heights our men reply,Sounding aloud the signal of their horns;Etcheco Jauna whets his arrows then.3They come! They come! See, what a wood of spearsWhat flags of myriad tints float in the midst!What lightning-flashes glance from off their arms!How many be they? Count them well, my child.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12,13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.4Twenty, and thousands more!’Twere but lost time to count.Our sinewy arms unite, tear up the rocks,Swift from the mountain tops we hurl them downRight on their heads,And crush, and slay them all.5What would they in our hills, these Northern men?Why come they here our quiet to disturb?God made the hills intending none should pass.Down fall the rolling rocks, the troops they crush!Streams the red blood! Quivers the mangled flesh!Oh! what a sea of blood! What shattered bones!6Fly, to whom strength remaineth and a horse!Fly, Carloman, red cloak and raven plumes!Lies thy stout nephew, Roland, stark in death;For him his brilliant courage naught avails.And, now, ye Basques, leaving awhile these rocks,Down on the flying foe your arrows shower!7They run! They run! Where now that wood of spears?Where the gay flags that flaunted in their midst?Rays from their bloodstained arms no longer flash!How many are they? Count them well, my child.20, 19, 18, 17, 16, 15, 14, 13,12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.8One! There is left not one. ’Tis o’er!Etcheco Jauna home with thy dog retire.Embrace thy wife and child,Thine arrows clean, and stow them with thine horn;And then, lie down and sleep thereon.At night yon mangled flesh shall eagles196 eat,And to eternity those bones shall bleach.(This translation is due to the kindness of a friend.)

The history of this song is very curious, and shows the little value of subjective criticism in any but the most competent hands. The MS. of it is alleged to have been found on the 5th of August, 1794, in a convent at Fuenterrabia, by La Tour d’Auvergne, the celebrated “premier grenadier” of the French Army. It was printed about the year 1835, by Monglave, and accepted as a genuine contemporary document by Fauriel, Chaho, Cenac-Moncaut, and many other French writers; by Lafuente, Amador de los Rios, and other Spanish authors; by Araquistain, and by the Editors of the “Revista Euskara” and of the “Cancionero Vasco” among the Basques. It is needless to say that all guide-books, tourist sketches, et hoc genus omne, have adopted it. It was inserted as genuine by Fr. Michel, in the Gentleman’s Magazine, in 1858, and in more recent years a translation appeared in another London magazine. In the “Basques et Navarrais” of M. Louis Lande, lately published, it is alluded to as genuine; and the Saturday Review of the 17th of August, 1878, quotes it as a corroboration of the ”Chanson de Roland.”197 There have been some, however, who have stoutly opposed these claims; among them M. Barry, of Toulouse, M. Gaston Paris, and M. J. F. Blade, which last writer, both in a separate pamphlet and in his “Études sur l’Origine des Basques” (Paris, 1859), has shown from internal grounds its want of authenticity. M. Alexandre Dihinx, a Basque, in a series of articles in the Impartial, of Bayonne, for 1873, which have since been reprinted by M. J. Vinson, in L’Avenir, of Bayonne, May of the present year, conclusively proved both the incorrectness and the modern character of its Basque. But all these authors seem either to have been unaware of, or to have unaccountably overlooked, the true history of the piece. When M. Fr. Michel published this, and another song called “Abarcaren Cantua,” in the Gentleman’s Magazine, in 1858, as specimens of ancient Basque poetry, a letter from M. Antoine d’Abbadie, Membre de l’Institut, appeared forthwith in the number for March, 1859, stating that the Abarca song had actually been among the unsuccessful pieces submitted for the prize in the poetical competition at Urrugne, of the previous August; and he adds:—

“I am sorry that the Altabiscarraco cantua, mentioned in your same number, is acknowledged as a gem of ancient popular poetry. Truth compels me to deny that it is universally admitted as such, for one of my Basque neighbours has often named the person who, about twenty four years ago, composed it in French, and the other person, who translated it into modern but indifferent Basque.198 The latter idiom, on purely philological ground, stands peerless among the most ancient languages in Europe, and I have felt it my duty to disclaim unfounded pretensions of which it has no need.—I am, etc.,

“Antoine d’Abbadie,

“London, Jan. 31, 1859.”

Correspond. de l’Institut de France.

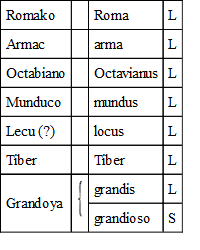

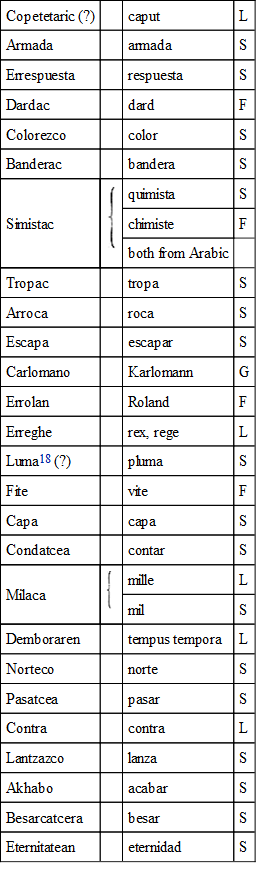

In the next number M. Fr. Michel writes, “henceforth I will believe that the songs called Abarcaren Cantua and Altabiscarraco Cantua are forgeries”; this testimony is decisive. It has often been repeated by M. d’Abbadie, with the additional assurance that he knows not only the house, but the very room in which the song was first composed. That the language is modern and indifferent Basque is very evident in the text given by M. Fr. Michel in “Le Pays Basque, Paris, 1857.” That above, taken from the “Cancionero Vasco” of the present year, is considerably corrected and improved. All attempts, and many efforts have been made, to force these irregular lines into any known form of Basque rhythm have hitherto signally failed. For the amusement of some of our readers we give below a list of the more evident foreign words in this and in the “Leloaren Cantua.” The relative antiquity will thus be seen at a glance:—

L, Latin; S, Spanish; F, French; G, German words.

Song of Lelo.

Song of Altabiscar

[18] Cf. lorea, from the Latin flos flore.

With reference to the above list we may observe that the Basque never begins a word with r, but always prefixes a euphonic er, ar, ir; hence er-respuesta, ar-roca, Er-rolan, er-rege, hir-risko, risque, F. In later copies editors have altered “Romaco,” in the “Song of Lelo,” into “Er-romaco,” to give it more of a Basque look. Aren, or aen, eco-aco-co are case terminations; tcea-cea marks the verbal noun. Carlomann was never the name of Charlemagne, but of his brother and his uncle. Er-rolan is evidently from the French Roland; neither from the Hruotlandus of Einhardus, nor from the Spanish Roldan. Defenders of the authenticity of the piece allege that these words are only corruptions, introduced in the course of ages; but our readers can judge for themselves how far they enter into the very structure of the composition.

The first book printed in Basque, the “Linguæ Vasconum Primitiæ, per Dominum Bernardum Echepare” (Bordeaux, 1545), is a collection of his poems, religious and amatory, the latter predominating. Echepare was the parish priest of the pretty little village of St. Michel, on the Béhérobie Nive, above St. Jean Pied de Port; and, if Nature alone could inspire a poet, he ought at least to have rivalled those of our own English Lakes. But, in truth, his verses are of scant poetical merit, and of little interest save as a philological curiosity.199 They belong so distinctly to that irritating mediocrity which never can be excused in a poet. After Echepare the next author is Arnauld Oyhenart, of Mauléon, who published a collection of his youthful Basque poems in Paris, 1657. These have, if anything, less poetical value than Echepare’s; but Oyhenart’s collection of proverbs and his “Notitia Utriusque Vasconiæ” will always make his name stand high among Basque writers. Except hymns and noëls (Christmas carols), of which many collections and editions have been published from 1630 downwards, and some of which are noteworthy on account of higher than mere poetical merit, the deep and evidently genuine spirit of piety they evince,200 little else is preserved much older than the present century. One ballad indeed there is, “The Betrothed of Tardetz,” which may be somewhat older. No two versions of it are exactly alike, though the outline of the story is always the same. The Lord of the Castle of Tardetz wishes to give the elder of his two daughters in marriage to the King of Hungary, or of Portugal, as some have it. But the lady’s heart has been already won by Sala, the son of the miller of Tardetz, and she bitterly bewails being “sold like a heifer.” The bells which ring for her wedding will soon toll for her funeral. The romance in its present form is evidently incomplete, but apparently ended with the corpse of the bride being brought back to her father’s castle.

Most of the Basque songs, except the drinking ones, are set, more or less, in a minor key. The majority of the love songs would have been described by our forefathers as “complaints.” One of the prettiest, both in words and music, is the fragment entitled “The Hermitage of St. Joseph”:—