Полная версия

Полная версияMaster Wace, His Chronicle of the Norman Conquest From the Roman De Rou

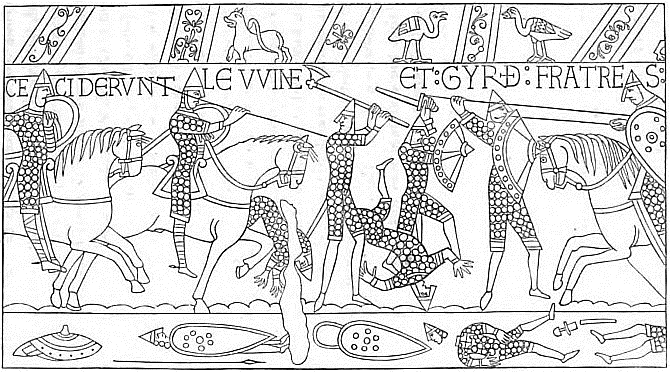

Gurth saw the English falling around, and that there was no remedy. He saw his race hastening to ruin, and despaired of any aid; he would have fled, but could not, for the throng continually increased. And the duke pushed on till he reached him, and struck him with great force. Whether he died of that blow I know not, but it was said that he fell under it, and rose no more.

The standard was beaten down, the golden gonfanon was taken, and Harold and the best of his friends were slain; but there was so much eagerness, and throng of so many around, seeking to kill him, that I know not who it was that slew him.

The English were in great trouble at having lost their king, and at the duke's having conquered and beat down the standard; but they still fought on, and defended themselves long, and in fact till the day drew to a close. Then it clearly appeared to all that the standard was lost, and the news had spread throughout the army that Harold, for certain, was dead; and all saw that there was no longer any hope, so they left the field, and those fled who could[4].

I do not tell, and I do not indeed know, for I was not there to see, and have not heard say, who it was that smote down king Harold, nor by what weapon he was wounded; but this I know, that he was found among the dead. His great force availed him nothing; amidst the slain he was found slain also349.

The English who escaped from the field did not stop till they reached London, for they were in great fear, and cried out that the Normans followed close after them350. The press was great to cross the bridge, and the river beneath it was deep; so that the bridge351 broke under the throng, and many fell into the water.

William fought well; many an assault did he lead, many a blow did he give, and many receive, and many fell dead under his hand. Two352 horses were killed under him, and he took a third when necessary, so that he fell not to the ground, and lost not a drop of blood. But whatever any one did, and whoever lived or died, this is certain, that William conquered, and that many of the English fled from the field, and many died on the spot. Then he returned thanks to God, and in his pride ordered his gonfanon to be brought and set up on high, where the English standard had stood; and that was the signal of his having conquered, and beaten down the standard. And he ordered his tent to be raised on the spot among the dead, and had his meat brought thither, and his supper prepared there.

But behold, up galloped Galtier Giffart; "Sire," said he, "what are you about? you are surely not fitly placed here among the dead. Many an Englishman lies bloody and mingled with the dead, but yet sound, or only wounded and besmeared with gore; tarrying of his own accord, and meaning to rise at night, and escape in the darkness353. They would delight to take their revenge, and would sell their lives dearly; no one of them caring who killed him afterwards, if he but slew a Norman first; for they say we have done them much wrong. You should lodge elsewhere, and let yourself be guarded by one or two thousand armed men, whom you can best trust. Let a careful watch be set this night, for we know not what snares may be laid for us. You have made a noble day of it, but I like to see the end of the work." "Giffart," said the duke, "I thank God, we have done well hitherto; and, if such be God's will, we will go on, and do well henceforward. Let us trust God for all!"

Then he turned from Giffart, and took off his armour; and the barons and knights, pages and squires came, when he had unstrung his shield; and they took the helmet from his head, and the hauberk from his back, and saw the heavy blows upon his shield, and how his helmet was dinted in. And all greatly wondered, and said, "Such a baron (ber) never bestrode warhorse, nor dealt such blows, nor did such feats of arms; neither has there been on earth such a knight since Rollant and Oliver."

Thus they lauded and extolled him greatly, and rejoiced in what they saw; but grieving also for their friends who were slain in the battle. And the duke stood meanwhile among them, of noble stature and mien; and rendered thanks to the king of glory, through whom he had the victory; and thanked the knights around him, mourning also frequently for the dead. And he ate and drank among the dead, and made his bed that night upon the field.

The morrow was Sunday; and those who had slept upon the field of battle, keeping watch around, and suffering great fatigue, bestirred themselves at break of day, and sought out and buried such of the bodies of their dead friends as they might find. The noble ladies of the land also came, some to seek their husbands, and others their fathers, sons, or brothers354. They bore the bodies to their villages, and interred them at the churches; and the clerks and priests of the country were ready, and, at the request of their friends, took the bodies that were found, and prepared graves and lay them therein.

King Harold was carried and buried at Varham355; but I know not who it was that bore him thither, neither do I know who buried him. Many remained on the field, and many had fled in the night.

CHAPTER XXV.

HOW WILLIAM WAS CROWNED KING; AND HOW HE AT LAST FELL ILL AT ROUEN

356.

[The duke placed a guard in Hastings357, from the best of his knights, so as to garrison the castle well, and went thence to Romenel358, to destroy it utterly, because some of his people had arrived there, I know not by what accident, and the false and traitorous had killed them by felony. On that account he was very wroth against them, and grievously punished them for it.

Proceeding thence, he rested no where till he reached Dover, at the strong fort he had ordered to be made at the foot of the hill. The castle on the hill was well garrisoned, and there all the goods of the country round were stored, and all the people had collected. The place being well fortified, and being out of the reach of any engines, they had made ready to defend themselves, and determined to contest the matter with the duke; and it was so well fenced in, and so high, and had so many towers and walls, that it was no easy matter to take it, as long as provisions should last.

The duke held them besieged there eight days; and during that time there were many fierce and bold assaults of the men and esquires. But the castle guards learnt that however long they might hold out, they must expect no succour, for that Harold the king was dead, and all the best of the English: and thus all saw plainly that the kingdom could no longer be defended. They dared not therefore longer keep up the contest, seeing the great loss they had sustained, and that do what they would it would not avail them long; so being forced by this necessity, they surrendered the castle, strong, rich, and fair as it was, to the duke, saving only their bodies and goods; and made their peace with him, all the men of the country swearing fealty to him. Then he placed a gallant and brave garrison in the castle; and before he parted thence all came to him from Cantorbire, both of high and low degree, and gave him their oaths and homage, and delivered hostages.

Stiganz was then archbishop of the city, as I read, who had greater wealth and more powerful friends than any other man of the country. In concert with the greatest men of the kingdom, and the sons of earl Algar359, who could not brook the shame of their people being so conquered, and would not suffer a Norman to obtain such honour, they had chosen and made their lord a knight and gallant youth called Addelin360, of the lineage of the good king Edward. Whether from fear or affection they made him king; and they rather chose to die than have for king in England one who was a stranger, and had been born in another land.

Towards London repaired all the great men of the kingdom, ready to aid and support Addelin in his attempt. And the duke, being desirous to go where he might encounter the greatest number of them, journeyed also to London, where the brave men were assembled ready to defend it. Those who were most daring issued out of the gates, armed, and on horseback; manœuvring against his people, to show how little they feared him, and that they would do nothing for him. When the duke saw their behaviour, he valued them not sufficiently to arm against them more than five hundred of his people. These, lacing their helmets on, gave the rein to their horses, angry and eager for the fray. Then might you see heads fly off, and swords cleaving body and ribs of the enemy.

Thus without any pause they drove all back again, and many were made prisoners, or lost their lives. And they set fire to the houses, and the fire was so great that all on this side the Thames was burnt that day.

Great grief was there in the city, and much were they discomforted. They had lost so much property, and so many people, that their sorrow was very heavy. Then they crossed the water, some on foot and some on horseback, and sought the duke at Walengeford, and stayed not till they had concluded their peace, and surrendered their castles to him. Then the joy of all was great; and archbishop Stiganz came there, and did fealty to duke William, and so did many more of the realm; and he took their homages and pledges. And Addelin was brought there also, whom they had foolishly made king. And Stiganz so entreated the duke, that he gave him his pardon, and then led all his force to London, to take possession of the city; and neither prince nor people came forth against him, but abandoned all to him, body, goods, and city, and promised to be faithful and serve him, and to do his pleasure; and they delivered hostages, and did fealty to him.]

Then the bishops by concert met at London, and the barons came to them; and they held together a great council. And by the common council of the clergy, who advised it, and of the barons, who saw that they could elect no other361, they made the duke a crowned king362, and swore fealty to him; and he accepted their fealty and homages, and so restored them their inheritances. It was a thousand sixty and six years, as the clerks duly reckon, from the birth of Jesus Christ when William took the crown; and for twenty and one years, a half and more afterwards, he was king and duke.

To many of those who had followed him, and had long served him, he gave castles and cities, manors and earldoms and lands, and many rents to his vavassors363.

Then he called together all the barons, and assembled all the English, and put it to their choice, what laws they would hold to, and what customs they chose to have observed, whether the Norman or the English; those of which lord and which king: and they all said, "King Edward's; let his laws be held and kept." They requested to have the customs which were well known, and which used to be kept in the time of king Edward; these pleased them well, and they therefore chose them: and it was done according to their desire364, the king consenting to their wish.

He had much labour, and many a war before he could hold the land in peace: but troubled as he was, he brought himself well out of all in the end. He returned to Normandy365, and came and went backward and forward from time to time, making peace here and peace there; rooting out marauders and harassing evil doers.

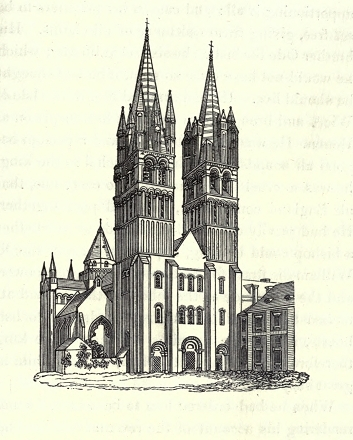

WHERE THE BATTLE HAD BEEN, HE BUILT AN ABBEY, AND PUT AN ABBOT THEREIN366.

The king of France called on the duke to do service to him for England, as he did for his other fief of Normandy; but William answered that he would pay him just as much service for England as he had received help towards winning it; that the king had not assisted him in his enterprize, nor helped him in his need; that he would serve him duly for his original fief, but owed him nought for any other; that if the king had helped him, and had taken part in the adventure, as he had requested, it might have been said that he held England of him: but that he had won the land without him, and owed no service for it to any one, save God and the apostle at Rome; and that he would serve none else for it.

Thus they wrangled together, but they afterwards came to an accord; and the king of France remained quiet, making no more demands on William. The French, however, often made war upon him and annoyed him; and he defended himself, and attacked them in return. One day he won, another he lost; as it often chances in war, that he who loses on one day gains on the next.

William was once sojourning at Rouen, where he had rested several days; for illness (I know not whence arising) pressed upon him, so that he could not mount his warhorse, nor bear his arms and take the field. The king of France soon heard that he was not in a condition to fight, and was in truth in bed; so he sent him word maliciously, that he was a long time lying in like a lady, and that he ought soon to get up, or he might lie too long. But William answered him, that he had not laid within too long yet; "Tell him," said he, "that when I get up, I will go to mass in his lands, and will make a rich offering of a thousand candles. My matches shall be of wood, and the points shall blaze with steel instead of fire."

This was his message, and when he had recovered, he accomplished what he had threatened. He led into France367 a thousand armed men with their lances set, the points gleaming with steel; and he burnt houses and villages on his route, till the king of France could see the blaze. He set fire even to Mantes, and reduced the whole place to ashes; so that borough, city, and churches were all burnt together. But as he passed through the city mounted on his favourite horse, it put its foot upon a heap of live ashes, and instantly starting back, gave a sudden plunge. The king saved himself from falling, but wounded himself sorely against the pommel of the saddle, upon which he was thrown. He returned with his men back to Rouen, and took to his bed; and as his malady increased, he caused himself to be carried to Saint-Gervais, in order that he might be there in greater quiet and ease368.

Then he gave his land to his sons, in order that there might be no dispute after his death. He called together his barons369, and said, "Listen to me, and see that ye understand. Normandy my inheritance, where the most of my race are, I give to Robert my son, the eldest born; and so I had settled before I came to be king. Moreover I give him Mans. He shall have Normandy and Mans, and serve the king of France for the same. There are many brave men in Normandy; I know none equal to them. They are noble and valiant knights, conquering in all lands whither they go. If they have a good captain370, a company of them is much to be dreaded; but if they have not a lord whom they fear, and who governs them severely, the service they will render will soon be but poor. The Normans are worth little without strict justice; they must be bent and bowed to their ruler's will; and whoso holds them always under his foot, and curbs them tightly, may get his business well done by them. Haughty are they and proud; boastful and arrogant, difficult to govern, and requiring to be at all times kept under; so that Robert will have much to do and to provide, in order to manage such a people.

"I should greatly desire, if God so pleased, to advance my noble and gallant son William. He has set his heart upon England, and it may be that he will be king there; but I can of myself do nothing towards it, and you well know the reason. I conquered England by wrong371; and by wrong I slew many men there, and killed their heirs; by wrong I seized the kingdom, and of that which I have so gained, and in which I have no right, I can give nought to my son; he cannot inherit through my wrong. But I will send him over sea, and will pray the archbishop to grant him the crown; and if he can in reason do it, I entreat that he will make him the gift.

"To Henry my son, the youngest born, I have given five thousand livres, and have commanded both William and Robert, my other sons, that each, according to his power, will, as he loves me, make Henry more rich and powerful than any other man who holds of them."

CHAPTER XXVI.

HOW WILLIAM DIED, AND WAS BURIED AT CAEN

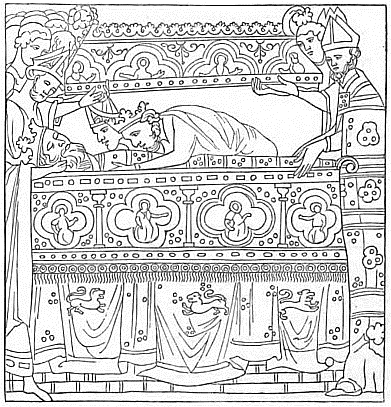

William lay ill six weeks; his sickness was heavy and increased. He made confession of his sins to the bishops and abbots, and the tonsured priests, and afterwards received the CORPUS DOMINI. He dispossessed himself of his wealth, devising and apportioning it all: and caused his prisoners to be set free, giving them quittance of all claims. His brother Odo the bishop he also set at liberty; which he would not have done so soon, if he had thought he should live. He had arrested him in the Isle of Wic372, and brought him and put him in prison at Rouen. He was said to be crafty and rapacious beyond all bounds; and when seneschal to the king, he was so cruel and treacherous to every one, that all England complained, rich and poor together. He had privily consulted his friends as to whether a bishop could be king, hoping to succeed should William die first; for he trusted in his great power, and the multitude of the followers that he had attached to himself by his large words and foolish boasts, and by the promises he made. The king therefore thought very ill of him, and held him in great suspicion.

When he had ordered him to be seized, for not rendering his account of the revenue that he had collected in England while he held it for the king, there was no baron who would touch him, or durst put forth his hand against him. Then the king himself sprang boldly forward, and seized him by the 'ataches,' and drew him forth out of the circle of his friends; "I arrest thee," said he, "I arrest thee." "You do me wrong," said Odo; "I am a bishop and bear crozier, and you ought not to lay hand on me." "By my head," quoth the king, "but I ought; I will seize the earl of Kent my bailiff and steward, who has not accounted to me for my kingdom that he has held." Thus was the bishop put in custody, and so remained for four years; for the ship was ready and the wind fair, and he was put on board, and carried by sea to Rouen, and kept in the tower there four years, and was not like to come out thence till the king should die.

On the morn of the eighth day of September the king died, and left this world as the hour of PRIME373 struck; he heard it well, and asked what it was that was striking. Then he called upon God as far as his strength sufficed, and on our holy Lady, the blessed Mary, and so departed, while yet speaking, without any loss of his senses or change in speech.

Many a feat of arms had he done; and he had lived sixty and four years; for he was only seven years old when duke Robert took the cross and went to Jerusalem.

At the time when the king departed this world, many of his servants were to be seen running up and down, some going in, others coming out, carrying off the rich hangings and the tapestry, and whatever they could lay their hands upon. One whole day elapsed before the corpse was laid upon the bier; for they who were before wont to fear him, now left him lying alone.

But when the news spread, much people gathered together, and bishops and barons came in long procession; and the body was well tended, opened, anointed, embalmed, and carried to Caen as he had commanded. There was no bishop in the province, nor abbot, earl, or noble prince, who did not repair to the interment of the body, if he could; and there were besides many monks, priests, and clerks.

When they had duly arranged the body, they sang aloud 'LIBERA ME.' They carried it to the church374, but the bier was yet outside the door when behold! a cry was heard which alarmed all the people, that the town was on fire; and every one rushed thither, save the monks who remained by the body. When the fire was quenched the people returned back, and they took the body within the church; and the clerks did their office, and all with good will chaunted 'REQUIEM ETERNAM.'

While they were yet engaged in preparing the grave where the corpse was to lie, and the bishops and the barons stood around, lo! a vavassor, whose name was Acelin, the son of Arthur, came running and burst through the throng. He pressed boldly forward, and mounted aloft upon a stone, and turned towards the bier and appealed to the clerks and bishops, while all the people gazed upon him. "Lords," cried he aloud, "hearken unto me! I warn all and forbid ye, by Jesu the almighty, and by the apostle of Rome—by greater names I cannot adjure ye—that ye inter not William in the spot where ye are about to lay him. He shall not commit trespass on what is my right, for the greater part of this church is my right and of my fee, and I have no greater right in any of my lands. I neither sold nor pledged it, forfeited it, nor granted it away. He made no contract with me, and I received no price for it from him. By force he took it from me, and never afterwards offered to do me right. I appeal him therefore by name, that he do me right, in that judgment where all alike go, before him who lieth not. Before ye all I summon him by name, that he on that day render me justice for it!"

When he had said this, he came down. Forthwith arose great clamour in the church, and there was such tumult that no one could hear the other speak. Some went, others came; and all marvelled that this great king, who had conquered so much, and won so many cities, and so many castles, could not call so much land his own as his body might lie within after death.

But the bishops called the man to them, and asked of the neighbours, whether what he had said were true; and they answered that he was right; that the land had been his ancestors' from father to son. Then they gave him money, to waive his claim without further challenge. Sixty sols gave they to him, and that price he took, and released his claim to the sepulchre where the body was placed. And the barons promised him that he should be the better for it all the days of his life375. Thus Acelin was satisfied, and then the body was interred.

CONCLUSION

KING WILLIAM'S CHARACTER, FROM THE SAXON CHRONICLE 376Las! how false and how unresting is this earth's weal! He that before was a rich king, and lord of many lands, had then of all his lands but seven feet space; and he that was whilom clad with gold and gems, lay there overspread with mould! If any one wish to know what manner of man he was, or what worship he had, or of how many lands he were the lord, then will we write of him, as we have known him; for we looked on him, and somewhile dwelt in his herd377.

This king William that we speak about was a very wise man, and very rich; more worshipful and stronger than any his foregangers were. He was mild to the good men that loved God, and beyond all metes stark to those who withsaid his will. On that same stede where God gave him that he should win England, he reared a noble minster, and set monks there and well endowed it.

Eke he was very worshipful. Thrice he bore his king-helm378 every year, as oft as he was in England. At Easter he bore it at Winchester; at Pentecost at Westminster; at midwinter at Glocester. And then were with him all the rich men over all England; archbishops and diocesan bishops; abbots and earls; thanes and knights. Truly he was eke so stark a man and wroth, that no man durst do any thing against his will. He had earls in his bonds, who had done against his will. Bishops he setoff their bishoprics; and abbots off their abbacies; and thanes in prisons. And at last he did not spare his brother Odo; him he set in prison. Betwixt other things we must not forget the good frith379 that he made in this land; so that a man that was worth aught might travel over the kingdom with his bosom full of gold unhurt. And no man durst slay another man, though he had suffered never so mickle evil from the other.