Полная версия

Полная версияMaster Wace, His Chronicle of the Norman Conquest From the Roman De Rou

173

William of Poitiers mentions only the last of these proposals, and says that it greatly alarmed Harold; on the same grounds, no doubt, as Gurth had urged, against a vassal's coming into personal conflict with one to whom he was bound in fealty, especially when ratified by an oath; notwithstanding an entirely fraudulent creation of the pledge in the first instance.

174

Benoit follows the story that Harold had planned a surprise on William's army, and had sent another force round by sea to intercept his retreat.

La nuit que li ceus fu teniègres,Soprendre quidout l'ost NormantEn la pointe del ajornant,Si qu'el champ out ses gens arméesE ses batailles devisées:Enz la mer out fait genz entrerPor ceus prendre, por ceus garderQui de la bataille fuireient,E qui as nefs revertireient.Treis cenz en i orent e plus.Dès ore ne quident que li duxLor puisse eschaper, ne seit pris,Ou en la grant bataille occis.175

We make no attempt to translate Wace's Saxon; for which a previous examination of his original MS. not now in existence, would certainly be a necessary preliminary. The existing copies are obviously the work of French transcribers, wholly ignorant, no doubt, of the Saxon. The MS. of Duchesne is said to read, for the two first words, 'bufler' and 'welseil,' Three of the words sound at least like 'wassail,' 'drink to me,' and 'drink health' or 'half.' In the appendix to M. Raynouard's observations on Wace, some suggestions are given from high English authority; but they throw very little light upon the matter. See Jeffrey of Monmouth's story of Vortigern and Rowena. Robert de Brunne, in translating the passage, makes Rowena give this explanation of the Saxon custom:

This is ther custom and ther gestWhan thei are at the ale or fest;Ilk man that loves where him thinkSall say wassail, and to him drink.He that bids sall say wassail;The tother sall say again drinkhail;That said wassail drinkes of the cup,Kissand his felow he gives it up;Drinkhail, HE says, and drinkes thereof,Kissand him in bord and skof.The king said, as the knight gan ken,Drinkhail, smiland on Rouwen;Rouwen drank as hire list,And gave the king, sine him kist.Ther was the first wassail in dede,And that first of fame gede;Of that wassail men told grete tale, &c.176

JEFFERY DE MOUBRAY,—Molbraium in Ordericus Vitalis,—chief justiciary of England. See in Cotman's Normandy, vol. i. p. 111, details concerning the munificent spirit of this prelate; and of the cathedral of Coutances, to the erection of which he dedicated his immense wealth. See also Ellis, Domesday, i. 400. The Moubray family at the conquest consisted of the bishop, his brother Roger, whom we shall find noticed below, and a sister Amy, married to Roger d'Aubigny, or de Albini, ancestor of the earls of Arundel. Roger Moubray's son Robert succeeded to the bishop's estates, comprising, it is said, 280 manors in England, and he became earl of Northumberland. At his disgrace not only his estates, but his wife passed to his cousin Nigel d'Aubigny, Amy's son, whose descendants took the name of Moubray. The scite of the castle of Monbrai is in the arrondissement of St. Lo. In the Norman Roll, red book of the Exchequer, we find 'Nigellus de Moubrai 5 mil. de honore de Moubrai, et de castro Gonteri: et ad servituum suum xi mil. quart. et octav.'

177

ODO, the bishop of Bayeux; son of Herluin, the knight who married Arlette, William's mother.

178

These transactions have been noticed in an earlier portion of our Chronicle, see page 35.

179

Guildford.

180

Henry of Huntingdon puts quite a different speech into William's mouth, reminding the Normans of their capture and detainer of the king of France, till he delivered Normandy to duke Richard, and (as the chronicler states) assented to the stipulation, that in conferences between the king and the duke,—the latter should wear his sword, but the king not even a knife. L'Estoire de Seint Ædward le rei makes William use similar expressions, but on a different occasion, that of rallying his men.

181

A ço ke Willame diseit,Et encore plus dire voleit,Vint Willame li filz Osber,Son cheval tot covert de fer;"Sire," dist-il, "trop demoron,Armons nos tuit; allon! allon!"Issi sunt as tentes alé, &c.See the observations of M. Deville on this description, in Mém. Ant. Norm. v. 81. Such an equipment of a horse at so early a period has no other authority, and is probably an anachronism. But it may be observed that Wace's description at least shows that the practice was already in existence in his day, which we believe could not be otherwise proved.

182

This circumstance is also told by William of Poitiers. In the Estoire de Seint Ædward le rei the scene of the reversed hauberk is thus described;

Li ducs, ki s'arma tost après,Sun hauberc endosse envers.Dist ki l'arma, "Seit tort u dreitVerruns ke li ducs rois seit,"Li ducs, ki la raisun ot,Un petit surrist au mot,Dist, "Ore seit a la deviseCelui ki le mund justise!"183

Sent perhaps on the occasion of the betrothment of William's daughter to the king of Gallicia, which has been before mentioned.

184

'Gueldon' is Wace's word here and elsewhere; which M. Pluquet interprets—a peasant armed with a long lance or pike.

185

RALF DE CONCHES, in the arrondissement of Evreux,—sometimes called de Tony, or Toëny, which is in the commune of Gaillon, arrondissement of Louviers,—son of Roger de Tony, hereditary standard bearer of Normandy. Ralf is a landholder in Domesday; Saham-Tony in Norfolk still records the name. His father founded the abbey of Conches. See Ellis, Introduction to Domesday, i. 493. In the Norman roll in the Red book of the Exchequer, we find, 'de honore de Conches et de Toeneio 44 mil. et 6 mil. quos Matheus de Clara tenet: preter hoc quod comes de Albamarâ, et comes Hugo Bigot, et Hugo de Mortuomari tenent de fœdo illo: ad servitium vero regis nesciunt quot.'

186

WALTER GIFFART, lord of Longueville, in the arrondissement of Dieppe, son of Osbern de Bolbec, and Aveline his wife, sister of Gunnor, the wife of duke Richard I. In reference to the allusions in the text to Walter Ginart's age, M. Le Prévost observes that it was his son, a second of the name, who lived till 1102, having been made earl of Buckingham. See Introd. Domesday, vol. i. 484; also vol. ii. 23, as to an Osbern Giffart. In the Norman roll of the Red book, 'De honore comitis Giffardi 98 mil. et dim. et quartem partem et 2 part, ad serv. com.' He is also among the knights holding of the church of Bayeux '1 mil.'

187

William's customary oath. Wace has before said, vol. ii. 51:

Jura par la resplendor Dé,Ço ert surent sun serement.188

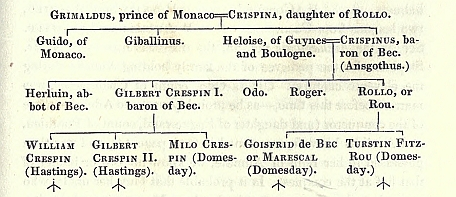

TURSTINUS FILIUS ROLLONIS vexillum Normannorum portavit: Orderic. Vit.. Several Normans bore the name of Toustain or Turstin as a baptismal name: but it afterwards became the family name of a noble house in upper Normandy; who, in memory of the office performed at Hastings, took for supporters of their arms, two angels, each bearing a banner. A.L.P. Turstin Fitz-Rou received large English estates in England. Besides Turstin there is a Robert Fitz-Rou in Domesday, possibly his brother. See our subsequent note on Gilbert Crespin and his family, to which Turstin belonged; and see Introd. Domesday, i. 479, 497.

189

Bec-aux-Cauchois, in the arrondissement of Ivetot; not Bec-Crespin, in that of Havre.

190

ROGER, son of Hugh de Montgomeri. He was lord of Montgomeri, in the arrondissement of Lisieux; of Alençon and of Bellesme, in right of his wife Mabel; he became earl of Shrewsbury, of Chichester and Arundel, and died 1094. See Introd. Domesday, i. 479. According to Ordericus Vitalis, A.D. 1067, Roger remained in Normandy during the expedition.

191

Lord of Breteuil; seneschal of the duke as has been before mentioned.

192

Poix in Picardy, and Boulogne-sur-mer. Wace seems to omit EUSTACE OF BOULOGNE, conspicuous in other historians. AIMERI was viscount of Thouars.

193

'Soldéiers' is used by Wace in its strict sense, of men serving merely for hire.

194

'Gueldon,' as before.

195

'Chapels,' perhaps hoods.

196

'Panels.'

197

'Gambais.' See before, page 22, as to cognizances and banners.

198

Huntingdon. When Wace's orthography is peculiar, we follow it. For Bed, which seems a repetition of Bedford, M. de la Rue's MS. reads Bedi. Eurowic is York; Nichol—Lincoln; Salebiere—Salisbury; Bat—Bath; Hontesire—Hampshire; Brichesire—Berkshire.

199

'Vassal.'

200

'Gisarmes.' "Wace mentions the gisarme as an exceedingly destructive weapon, used by the Saxons at the battle of Hastings: but by the Gisarme he evidently means the 'byl,' to which he gives a Norman name:"—see Hist. of British costume, 1834, page 33. The Saxons used also the bipennis, or 'twy-byl.' The bill was an axe with long handle. Benoit mentions 'haches Danoises,' which probably were the double axes. See also Maseres's note on William of Poitiers, 129. Wace afterwards says of the hache of an English knight:

Hache noresche out mult bele,Plus de plain pié out l'alemele.201

'Geldon.'

202

'Haches.'

203

'Gisarmes.'

204

Even down to the fifteenth century the Normans are said to have called the English 'courts vestus.' See the songs at the end of the Vaux-de-vires of Olivier Basselin.

205

This seems further explained afterwards by the description of the English knight's helmet:

Un helme aveit tot fait de fust,Ke colp el chief ne réceust;A sez dras l'aveit atachié,Et environ son col lacié.But the text is often so imperfect, and at such variance from the ordinary rules of Norman French grammar, that it is frequently hard to be certain as to the fidelity of a translation.

206

Ordericus Vitalis states that the spot where the battle was fought was anciently called SENLAC. That word certainly sounds very like French, and as originating in the blood which flowed there: but his expression has been thought to carry the antiquity of the name, in his opinion at least, much earlier than the date of the battle. We think it right to subjoin Wace's original record of the privileges of the men of Kent and London; as to which see Palgrave's Rise and progress of the English Common-wealth, I. ccclxxii.

Kar ço dient ke cil de KentDeivent ferir primierement;U ke li reis auge en estor,Li premier colp deit estre lor.Cil de Lundres, par dreite fei,Deivent garder li cors li rei;Tut entur li deivent ester,E l'estandart deivent garder.207

Holy cross. M. de la Rue's MS. reads 'Alicrot.'

208

God Almighty.

209

Bishop Guy, in his Carmen de bello Hastingensi, thus describes Taillefer,

'INCISOR FERRI mimus cognomine dictus.'He is there also called 'histrio,' but his singing is not mentioned.

'Hortatur Gallos verbis, et irritat Anglos;Alte projiciens ludit et ense suo,'An Englishman starts out of the ranks to attack him, but is slain by the 'incisor ferri,' who thus

'—belli principium monstrat et esse suum.'Nothing is said as to his fate, which Wace also passes over.

210

It has been contended that Wace misunderstood Taillefer's song, which the Latin historians call 'Cantilena Rollandi;' and it has been further conjectured that what was meant was a song of Rollo, or possibly of Rognavald his father; that out of this latter name the French minstrels formed Rolland; and that Wace confounded him with Charlemagne's Paladin. See Sharon Turner's History of England; the Abbé de la Rue's late work, vol. i. 143; and M. Michel's Examen critique du roman de Berte aux grans piés, Paris, 1832. We must refer the reader to these authorities on the controversy. The probability we must say, however, appears to us to be, that the minstrelsy selected by a French jugleor, to stimulate the army, (great part of which was, in fact, strictly French,) would be French, both in subject and language. Wace perfectly well knew the race of jogleors and their themes, which he quotes; as in the case of William Longue-espée, of whose deeds he says, 'a jogleors oï en m'effance chanter.'

211

It has been remarked, as somewhat singular, that Wace should omit a circumstance calculated to add to the poetic effect of his story; namely, Taillefer's slight of hand exhibition, related by other historians as having been played off by him in front of the two armies. Perhaps Wace's abstinence, in this and other cases which might be noticed, (after his history reaches the boundary of more authentic evidence than his earlier chronicle had had to deal with), is in favour of his credibility, under circumstances where he had the means of obtaining accurate information.

212

What Benoit de Sainte-More says on the subject of Taillefer's exploit will be found in our appendix, Gaimar's account, which will be found there also, is blended in the English paraphrase given in the Archæiologia, vol. xii. which is a compound of the two chroniclers.

213

OUT, In the MS. of the British Museum, a letter has evidently been erased before 'ut,' the present reading. An addition to the text, which is found in the MS. 6987 of the Bib. Royale at Paris, seems to determine what word is meant:

Cou est l'ensegne que jou diQuant Engles saient hors a cri.214

Though the details vary much, all the historians attribute great loss to circumstances of this sort. William of Poitiers distinguishes,—and perhaps Wace also meant to do so,—between the fosse which guarded the English camp, and other fosses into which the Normans fell in the pursuit. The Chronicle of Battle Abbey (MS. Cott. Dom. ii.), speaking of the principal fosse, says 'quod quidem baratrum, sortito ex accidenti vocabulo, Malfossed hodieque nuncupatur.' Benoit attributes great loss to a report of William's fall, whereupon he,

Son chef desarme en la batailleE del heaume e de la ventaille.Count Eustace is here introduced by Benoit as strongly exhorting the duke to escape from the field, considering the battle as lost beyond recovery. He however rallies his men, and triumphs over the English, whose ranks had broken in the pursuit. No stratagem in this respect is noticed by Benoit.

215

The author of the continuation of Wace's Brut d'Angleterre, says, as to the duration of the battle,

La bataille ad bien duréDe prime dekes a la vespré:Unkes home ne saveitKi serreit vencu, ne ki vencreit.Ne longe wespe, ne cornet.216

This word seems used in a metaphorical sense. In the Fables of Marie de France, vol. ii. 243, we find

Ne grosse mouske, ne wibet,217

'Hache noresche.' See note before at page 175.

218

'Coignie.'

219

'Gisarmes.'

220

'Gibet.'

221

From Brompton. A few names have already occurred, such as FITZ OSBERN, RALF DE CONCHES, WALTER GIFFART, ROGER DE MONGOMERI, the counts d'OU and of MORTAIN, ROGER DE BEAUMONT, TURSTIN FITZ ROU, the sire de DINAN, FITZ BERTRAN DE PELEIT, and AIMERI of THOUARS. The only chiefs mentioned by the Latin historians, and apparently omitted by Wace, are EUSTACE, count of BOULOGNE, and WILLIAM, son of Richard count of EVREUX. The case is doubtful as to JEFFREY, son of Rotro count of MORTAGNE—comes Moritoniæ; not to be confounded with Robert, count of Mortain—comes Moritolii. Jeffrey is perhaps mentioned by Wace; see our note below on JEFFREY DE MAYENNE.

222

ROGER DE BEAUMONT; see as to him the former note, p. 102. William of Poitiers states that he did not join the expedition, but remained in Normandy. According to that historian and Ordericus Vitalis, the one present at the battle was Roger's son—the 'tyro' Robert—who, by inheritance, took the title of count of Mellent. The British Museum MS. of Wace in fact reads ROBERT; though the epithet 'le viel' is not appropriate to his then age. By their alliance with the Fitz Osberns, the earls of Leicester and Mellent acquired a portion of the Norman lands of that family. In the Red book roll we have, 'comes Mell. 15 mil. et ad servitium suum 63 mil. et dim.' 'comes Leycestr. 10 mil. de honore de Grentemesnil, et ad servitium suum 40 mil. Idem 80 mil. et 4m. part. quos habet ad servitium suum de honore de Britolio: et faciet tantum quod honor sit duci et com. in Fales.'

223

WILLIAM MALET died before Domesday, which says, 'W. Malet fecit suum castellum ad Eiam,' in Suffolk. His son Robert then held the honor of Eye, 'olim nobile castellum,' (where he founded a monastery), and other estates. Introd. Dom. i. 449.

224

MONTFORT SUR RILLE, arrondissement of Pont-Audemer. Four lords of this place successively bore the name of Hugh. It is presumed the conqueror's attendant was Hugh II.—son of Hugh 'with the beard,' (the son of Turstan de Bastenberg) mentioned before at page 8. He was one of the barons to whom William, when he visited Normandy in 1067, left the administration of justice in England. The scite of the castle is still visible near the bourg of Montfort. Mém. Ant. Norm. iv. 434. Dugdale's Baronage, and the Introd. to Domesday, i. 454, treat Hugh 'with the beard' himself as having been William's attendant. See the pedigree prefixed to Wiffen's History of the Russells, and that in Duchesne. In the Bayeux Inquest of 1133 (Mém. Ant. Norm, viii.) 'Hugo de Monteforte tenet feodum viii mil.' The same appears in the Red book roll; where we also find 'de honore de Monteforte 21 mil. et dim. et duas partes et 4m. part.' with other particulars.

225

Dam, or Dan—Dominus—is often used by Wace. ROBERT, not William, lord of VIEUX-PONT, appears to have been at Hastings. In 1073 he was sent to the rescue of Jean de la Fleche. He came probably from Vieux-pont-en-Auge, arrondissement of Lisieux. The name, afterwards written Vipount, is known in English history. A.L.P. In the Red book roll, 'Fulco de Veteri Ponte 2 mil. et ad servitium suum 10 mil. et quartam partem.' 'Willmus de Veteri Ponte 2 mil. et ad servit. suum xi mil. et 4 part.

226

The Brit. Mus. MS. reads 'cil de Beessin,' not cels. If this be correct, Wace may here mean the viscount of the Bessin, RANOULF DE BRICASART, whom we have met at Valdesdunes.

227

Wace's annotator, M. Le Prevost, is incredulous as to the fact of NEEL de Saint Sauveur-le-vicomte (near Valognes) having been at the conquest. He was banished after his rebellion at Valdesdunes, and was subsequently pardoned, as his family afterwards held his estates; but no particulars or time are known. His presence at Hastings is vouched by no one else; not even by Brompton's list, where Sanzaver seems a variation of Saunzaveir or Sans-avoir, a family which settled in England. See M. de Gerville's Recherches, in Mém. Ant. Norm. Domesday is silent; but this does not appear conclusive, as he might have died in the interval; and M. de Gerville quotes on the subject M. Odolent Desnos, Hist. d'Alencon, i.149; where it is stated, though without quoting the authority, that Neel was killed in 1074, in battle near Cardiff. The last Neel de St. Sauveur died in 1092; as appears by an account of his relation, bishop Jeffery de Moubray's desire to attend his funeral: Mém. Ant. Norm. i. 286, ii. 46. One of his two daughters and heiresses married Jourdain Tesson; the other was mother to Fulk de Pratis; Hardy's Rot. Norm. 16.

228

RAOUL, son of Main, second of the name, lord of FOUGERES in Brittany. He, or a second Raoul, founded Savigny in 1112. A Ralf held large possessions in England at Domesday; and a William held in Buckinghamshire; Introd. Domesday, i. 418.

229

HENRY, lord of St. Hilaire de FERRIERES, arrondissement of Bernay, son of Walkelin de Ferrieres, ante page 8. The scite of the castle is still visible. In England, Henry de Ferrieres received the castle of Tutbury, and other large estates; see the Introd. Domesday, i. 418, and the Ferrers pedigree in Dugdale's Baronage. In the Red book Roll, 'Walkelinus de Ferrariis 5 mil. et ad servitium suum 42 mil. et 3 quartas—et 4 mil. cum planis armis.'

230

GILBERT CRESPIN was then lord of TILLIERES, arrondissement of Evreux. The building of the castle is described by Wace, i. 335. He is considered to have been a younger son of Gilbert I. mentioned before by Wace, vol. ii. 3. 5; and must not be confounded with Gilbert earl of Brionne, guardian to the duke. In the Red book, 'Gilbertus de Teuleriis 3 mil. et ad servitium suum 4 mil.' With reference to this family, (embracing Turstin Fitz-Rou above mentioned, and William Crespin, who will soon occur) Mr. Grimaldi has given in the Gentleman's Mag. Jan. 1832, some curious materials; bearing also on the probable origin of the Mareschals. His pedigree is as follows:

This pedigree differs, it will be seen, from the usually received accounts, and in some respects from the genealogy in the appendix to Lanfranci opera by D'Achery. Whether the latter is entitled to more weight than most of these monastic genealogies we do not pretend to decide. According to that authority, however, William Crespin had a sister Hesilia, who was mother of William Malet, who, it states, died an old man at Bec. She would thus appear to be the wife of Turstin Fitz-Rou, the grandfather of Vauquelin Malet.

231

See note, page 177, as to the English helmets.

232

'Coignie.'

233

ANISY and MATHIEU, two leagues from Caen.

234

AUMALE or ALBAMALE. See, in the Archæologia vol. 26, the materials furnished by Mr. Stapleton for the pedigree of the family holding Aumale during the eleventh century. Unless Odo, count of Champagne, was married before this time,—as he probably was,—to Adelidis, niece of the conqueror (and daughter of Enguerrand, count of Ponthieu, and Adelidis his wife, mentioned before, page 44), and was then possessed in her right of Aumale, we know no lord or holder of that fief at the conquest. Is it probable that Guy her uncle, who was released two years after the battle of Mortemer on doing homage to William, held Aumale during her minority, which possibly extended to 1066? Either assumption implies that Enguerran's widow was then dead, or that she did not hold Aumale, or at least that she did not after her daughter's marriage. The charter printed in the Archæologia treats the widow as having succeeded to the possession, (whether from having dower in it, or as guardian of her daughter, does not appear), and her daughter as following her. Of course the most likely solution of this difficulty, and of Wace's vague statement, is that he was ignorant of the facts; in which he is not singular; Ordericus Vitalis also is incorrect in his statements as to the family. No particulars of the fief of Aumale are in the Red book; the comes de Albamara being one of those, who 'nec venerunt nec miserunt, nec aliquid dixerunt.'