Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 476, February 12, 1831

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 17, No. 476, February 12, 1831

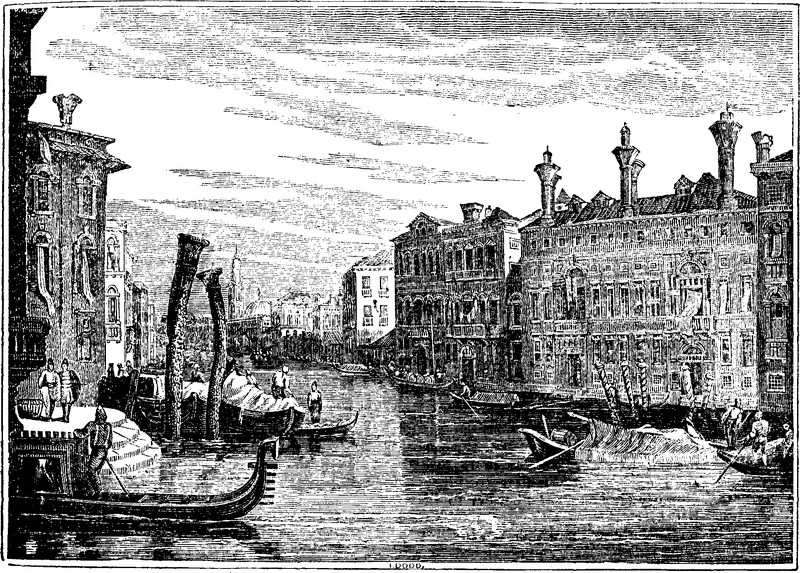

LORD BYRON'S PALACE, AT VENICE.

Scores of readers who have been journeying through Mr. Moore's concluding portion of the Life of Lord Byron, will thank us for the annexed Illustration. It presents a view of the palace occupied by Lord Byron during his residence at Venice. When, after his unfortunate marriage, he left England, "in search of that peace of mind which was never destined to be his," Venice naturally occurred to him as a place where, for a time at least, he should find a suitable residence. He had, in his own language, "loved it from his boyhood;" and there was a poetry connected with its situation, its habits, and its history, which excited both his imagination and his curiosity. His situation at this period is thus feelingly alluded to by Mr. Moore:—"The circumstances under which Lord Byron now took leave of England were such as, in the case of any ordinary person, could not be considered otherwise than disastrous and humiliating. He had, in the course of one short year, gone through every variety of domestic misery;—had seen his hearth eight or nine times profaned by the visitations of the law, and been only saved from a prison by the privileges of his rank. He had alienated, as far as they had ever been his, the affections of his wife; and now, rejected by her, and condemned by the world, was betaking himself to an exile which had not even the dignity of appearing voluntary, as the excommunicating voice of society seemed to leave him no other resource. Had he been of that class of unfeeling and self-satisfied natures from whose hard surface the reproaches of others fall pointless, he might have found in insensibility a sure refuge against reproach: but, on the contrary, the same sensitiveness that kept him so awake to the applauses of mankind rendered him, in a still more intense degree, alive to their censure. Even the strange, perverse pleasure which he felt in painting himself unamiably to the world did not prevent him from being both startled and pained when the world took him at his word; and, like a child in a mask before a looking-glass, the dark semblance which he had half in sport, put on, when reflected back upon him from the mirror of public opinion, shocked even himself. * * *

"Then came the disappointment of his youthful passion,—the lassitude and remorse of premature excess,—the lone friendlessness of his entrance into life, and the ruthless assault upon his first literary efforts,–all links in that chain of trials, errors, and sufferings, by which his great mind was gradually and painfully drawn out;—all bearing their respective shares in accomplishing that destiny which seems to have decreed that the triumphal march of his genius should be over the waste and ruins of his heart. He appeared, indeed, himself to have had an instinctive consciousness that it was out of such ordeals his strength and glory were to arise, as his whole life was passed in courting agitation and difficulties; and whenever the scenes around him were too tame to furnish such excitement, he flew to fancy or memory for 'thorns' whereon to 'lean his breast.'" At the same time, the melancholy with which his heart was filled was soothed and cherished by the associations which every object in Venice inspired. The prospects of dominion subdued, of a high spirit humbled, of splendour tarnished, of palaces sinking into ruins, was but too faithfully in accordance with the dark and mournful mind which the poet bore within him. Nor were other motives of a nature wholly different wanting to draw him to Venice.1 How beautifully has the poet illustrated this preference:—

In Venice Tasso's echoes are no more,And silent rows the songless gondolier;Her palaces are crumbling to the shore,And music meets not always now the ear:Those days are gone—but Beauty still is here.States fall, hearts fade—but Nature doth not die,Nor yet forget how Venice once was dear,The pleasant place of all festivity,The revel of the earth, the masque of Italy.But unto us she hath a spell beyondHer name in story, and her long arrayOf mighty shadows, whose dim forms despondAbove the dogeless city's vanish'd sway;Ours is a trophy which will not decayWith the Rialto; Shylock and the Moor,And Pierre, cannot be swept or worn away—The keystones of the arch! though all were o'er,For us repeopled were the solitary shore.Her desolation:—

Statues of glass—all shiver'd—the long fileOf her dead Doges are declined to dust;But where they dwelt, the vast and sumptuous pileBespeaks the pageant of their splendid trust;Their sceptre broken, and their sword in rust;Have yielded to the stranger: empty halls,Thin streets, and foreign aspects, such as mustToo oft remind her who and what enthrals,Have flung a desolate cloud o'er Venice' lovely walls.Thus, Venice, if no stronger claim were thine,Were all thy proud historic deeds forgot,Thy choral memory of the Bard divine,Thy love of Tasso, should have cut the knotWhich ties thee to thy tyrants; and thy lotIs shameful to the nations,—most of all,Albion! to thee; the Ocean queen should notAbandon Ocean's children; in the fallOf Venice think of thine, despite thy watery wall.I loved her from my boyhood—she to meWas as a fairy city of the heart,Rising like water-columns from the sea,Of joy the sojourn, and of wealth the mart;And Otway, Radcliffe, Schiller, Shakspeare's artHad stamp'd her image in me, and even so,Although I found her thus, we did not part,Perchance even dearer in her day of woeThan when she was a boast, a marvel and a show.I can repeople with the past—and ofThe present there is still for eye, and thought,And meditation chasten'd down, enough;And more, it may be, than I hoped or sought;And of the happiest moments which were wroughtWithin the web of my existence, someFrom thee, fair Venice! have their colours caught:There are some feelings Time can not benumb,Nor Torture shake, or mine would now be cold and dumb.Again, in the notes to Childe Harold, where these spirit-breathing lines occur:

"The population of Venice, at the end of the 17th century amounted to nearly two hundred thousand souls. At the last census, taken two years ago, it was no more than about one hundred and three thousand, and it diminishes daily. The commerce and the official employments, which were to be the unexhausted source of Venetian grandeur, have both expired. Most of the patrician mansions are deserted, and would gradually disappear, had not the government, alarmed by the demolition of seventy-two, during the last two years, expressly forbidden this sad resource of poverty. Many remnants of the Venetian nobility are now scattered and confounded with the wealthier Jews upon the banks of the Brenta, whose palladian palaces, have sunk, or are sinking, in the general decay. Of the 'gentil uomo Veneto,' the name is still known, and that is all. He is but the shadow of his former self, but he is polite and kind. The present race cannot be thought to regret the loss of their aristocratical forms, and too despotic government—they think only on their vanished independence. They pine away at the remembrance, and on this subject suspend for a moment their gay good humour. Venice may be said, in the words of the scripture, 'to die daily;' and so general and so apparent is the decline, as to become painful to a stranger, not reconciled to the sight of a whole nation, expiring as it were before his eyes. So artificial a creation having lost that principle which called it into life and supported its existence, must fall to pieces at once, and sink more rapidly than it rose."

Captain Medwin relates Lord Byron's detestation of Venice in unmeasured terms. He likewise tells of his Lordship performing here one of those aquatic feats in which he greatly prided himself; and the Countess Albrizzi mentions a similar incident: "He was seen, on leaving a palace situated on the grand canal, instead of entering his gondola, to throw himself, with his clothes on, into the water, and swim to his house."

The Countess, who became acquainted with his Lordship at Venice, also narrates a few particulars of the mode in which he passed his time in that city: Amongst his peculiar habits was that of never showing himself on foot. "He was never seen to walk through the streets of Venice, nor along the pleasant banks of the Brenta, where he spent some weeks of the summer; and there are some who assert that he has never seen, excepting from a window, the wonders of the Piazza di San Marco,2 so powerful in him was the desire of not showing himself to be deformed in any part of his person. I, however," continues the Countess, "believe that he often gazed on those wonders, but in the late and solitary hour, when the stupendous edifices which surrounded him, illuminated by the soft and placid light of the moon, appeared a thousand times more lovely." "During an entire winter, he went out every morning alone, to row himself to the island of the Armenians (a small island, distant from Venice about half a league), to enjoy the society of those learned and hospitable monks, and to learn their difficult language." During the summer, Lord Byron enjoyed the exercise of riding in the evening. "No sunsets," said he, "are to be compared with those of Venice—they are too gorgeous for any painter, and defy any poet."

NATURE REVIVING

POLISH PATRIOT'S APPEAL

(For the Mirror.)Rise fellow men! our country yet remainsBy that dread name, we wave the sword on high,And swear with her to live—for her to die.CAMPBELL.Have we not proved our country's worth—the country of the free?Have we not raised the tyrant's foot—and struck for liberty—The giant foot that on us fell, in war's tremendous fall—The mighty weight that bore us down and held our arms in thrall?Have we not risked our homes, our all, at Freedom's glorious shrine,And dared the vengeance of the Russ, whose sway is yclept divine?And have we not appealed to arms—our last and dearest right!And is not ours a sacred cause, a just and holy fight?Yes, on Sarmatia's bleeding form Oppression's fetters rang,And Liberty's last dying dirge the Northern trumpet sang:Our hopes were buried in the grave where Kosciusko lies;There came not friendship then from earth—nor mercy from the skies!But Heaven has roused the Polish slave and bid him rend his chains,And now we rank among the free—"Our country yet remains:"Again we seek our native rights by God and Nature given—A people's right unto their soil from us unjustly riven.We call upon the honoured brave—the free of every land—For succour from the powerful—for aid from every strand:We ask for every good man's prayer—we call for help on high;Ye shades of Poland's slaughtered sons, look on propitiously.We fight the fight of nations—bear witness field and stormTo our desert hereafter? Now we are but braggarts warm—But by our honest cause, we swear, ere they our land retake,Each town shall he a charnel tomb—each field a gory lake!CYMBELINETHE NATURALIST

ANECDOTES OF PARROTS

(For the Mirror.)"Who taught the Parrot human notes to try?'Twas witty want, fierce hunger to appease."DRYDEN.A parrot belonging to the sister of the Comte de Buffon (says Bingley,) "would frequently speak to himself, and seem to fancy that some one addressed him. He often asked for his paw, and answered by holding it up. Though he liked to hear the voice of children, he seemed to have an antipathy to them; he pursued them, and bit them till he drew blood. He had also his objects of attachment; and though his choice was not very nice, it was constant. He was excessively fond of the cook-maid; followed her everywhere, sought for, and seldom missed finding her. If she had been some time out of his sight, the bird climbed with his bill and claws to her shoulders, and lavished on her caresses. His fondness had all the marks of close and warm friendship. The girl happened to have a very sore finger, which was tedious in healing, and so painful as to make her scream. While she uttered her moans the parrot never left her chamber. The first thing he did every day, was to pay her a visit; and this tender condolence lasted the whole time of the cure, when he again returned to his former calm and settled attachment. Yet this strong predilection for the girl seems to have been more directed to her office in the kitchen, than to her person; for, when another cook-maid succeeded her, the parrot showed the same degree of fondness3 to the new comer, the very first day."

Bingley also says, "Willoughby tells us of a parrot, which when a person said to it, 'laugh, Poll, laugh,' laughed accordingly, and the instant after screamed out, 'What a fool to make me laugh.' Another which had grown old with its master, shared with him the infirmities of age. Being accustomed to hear scarcely anything but the words, 'I am sick;' when a person asked it, 'How do you do, Poll? how d'ye do?'—'I am sick,' it replied, in a doleful tone, stretching itself along, 'I am sick.'"

Goldsmith says, "That a parrot belonging to King Henry VIII. having been kept in a room next the Thames, in his palace at Westminster, had learned to repeat many sentences from the boatmen and passengers. One day sporting on its perch, it unluckily fell into the water. The bird had no sooner discovered its situation, than it called out aloud, 'A boat, twenty pounds for a boat.' A waterman happening to be near the place where the parrot was floating, immediately took it up, and restored it to the king; demanding, as the bird was a favourite, that he should be paid the reward that it had called out. This was refused; but it was agreed, that as the parrot had offered a reward, the man should again refer to its determination for the sum he was to receive. 'Give the knave a groat,' the bird screamed aloud, the instant the reference was made."

Mr. Locke, in his "Essay on the Human Understanding," has related an anecdote concerning parrots, of which (says Bingley) however incredible it may appear to some, he seems to have had so much evidence, as at least to have believed it himself. It is taken from a writer of some celebrity; the author of Memoirs of what passed in Christendom from 1672 to 1679. The story is this:—

"During the government of Prince Maurice, in Brazil, he had heard of an old parrot that was much celebrated for answering like a rational creature, many of the common questions that were put to it. It was at a great distance; but so much had been said about it, that his curiosity was roused, and he directed it to be sent for. When it was introduced into the room where the prince was sitting in company with several Dutchmen, it immediately exclaimed in the Brazilian language, 'What a company of white men are here.' They asked it 'Who is that man?' (pointing to the prince) the parrot answered, 'Some general or other.' When the attendants carried it up to him, he asked it through the medium of an interpreter, (for he was ignorant of its language) 'From whence do you come?' the parrot answered, 'From Marignan.' The prince asked, 'To whom do you belong?' it answered, 'To a Portuguese.' He asked again, 'What do you do there?' it answered, 'I look after the chickens.' The prince, laughingly, exclaimed, 'You look after the chickens?' the parrot in answer, said, 'Yes, I; and I know well enough how to do it,' clucking at the time, in imitation of the noise made by the hen to call together her young.

"This account came directly from the prince to the above author; he said that though the parrot spoke in a language he did not understand, yet he could not be deceived, for he had in the room both a Dutchman who spoke Brazilian, and a Brazilian who spoke Dutch; that he asked them separately and privately, and both agreed very exactly in giving him the parrot's discourse. If the story is devoid of foundation, the prince must have been deceived, for there is not the least doubt that he believed it."

Parrots not only discourse, but also mimic gestures and actions. Scaliger saw one that performed the dance of the Savoyards, at the same time that it repeated their song.

P.T.WRETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

DITTY BY QUEEN ELIZABETH

(For the Mirror.)"I find, (says Puttenham,) none example in English metre so well mayntayning this figure (Exargasia, or the Gorgeous) as that dittie of her Majestie Queen Elizabeth's own making, passing sweete and harmonical; which figure being, as his very original name purporteth, the most beautiful and gorgeous of all others, it asketh in reason to be reserved for a last compliment, and disciphered by the arte of a ladies penne (herself being the most beautifull or rather beautie of Queens.) And this was the occasion: Our Sovereign lady perceiving how the Queen of Scots residence within this realme as to great libertie and ease (as were scarce meete for so great and dangerous a prisoner,) bred secret factions amongst her people, and made many of the nobility incline to favour her partie (some of them desirous of innovation in the state, others aspiring to greater fortunes by her libertie and life;) the Queene our Sovereigne Lady, to declare that she was nothing ignorant of those secret practices (though she had long, with great wisdom and patience, dissembled it,) writeth that dittie, most sweet and sententious; not hiding from all such aspiring minds the danger of their ambition and disloyaltie, which afterwards fell out most truly by the exemplary chastisements of sundry persons, who in favour of the said Queen of Scots, declining from her Majestie, sought to interrupt the quiet of the realm by many evill and undutifull practyses."

The ditty is as followeth:—

The dowbt of future foes exiles my present joy,And Wit me warns to shun snares as threaten mine annoy;For falshood now doth flowe, and subject faith doth ebbe,Which would not be, if reason rul'd, or wisdom weav'd the webbe.But clouds of tois untried do choake aspiring mindes,Which turn'd to rain of late repent by course of changed windes.The toppe of hope suppos'd, the root of ruth will beAnd fruitless all their grafted guiles, as shortly ye shall see.Then dazzled eyes, with pride which great ambition blindes,Shall be unveil'd by worthy wights, whose foresight falshood finds.The daughter of debate, that eke discord doth sowe,Shall reape no gaine, where former rule hath taught still peace to growe.No forreine banish'd wight shall ancre in this port;Our realme it brooks no stranger's force, let them elsewhere resort.Our rusty sword with rust shall first his edge employ,To polle their toppes that seeke such change, and gape for joy.J.G.BNOTES OF A READER

QUARTERLY REVIEW. No. 87

Character of Mr. CanningThere have been some who equalled him in acquirements—many who have possessed sounder judgment and sounder principles; but never was there in any legislative assembly, a person whose talents were more peculiarly and perfectly adapted to the effect which he intended to produce. With all the advantages of voice and person—with all the graces of delivery—with all the charms which affability and good-nature impart to genius, he had wit at will, as well as eloquence at command. Being frank and sincere in all his political opinions, he had all that strength in his oratory which arises from sincerity, although in his political conduct the love of intrigue was one of his besetting sins. By an unhappy perversion of mind it seemed as if he would always rather have obtained his end by a crooked path than by a straight one; but his speeches had nothing of this tortuosity; there was nothing covert in them, nothing insidious—no double-dealing, no disguise. His argument went always directly to the point, and with so well-judged an aim that he was never (like Burke) above his mark—rarely, if ever, below it, or beside it. When, in the exultant consciousness of personal superiority, as well as the strength of his cause, he trampled upon his opponents, there was nothing coarse, nothing virulent, nothing contumelious, nothing ungenerous in his triumph. Whether he addressed the Liverpool electors, or the House of Commons, it was with the same ease, the same adaptation to his auditory, the same unrivalled dexterity, the same command of his subject and his hearers, and the same success. His only faults as a speaker were committed when, under the inebriating influence of popular applause, he was led away by the heat and passion of the moment. A warm friend, a placable adversary, a scholar, a man of letters, kind in his nature, affable in his manners, easy of access, playful in conversation, delightful in society—rarely have the brilliant promises of boyhood been so richly fulfilled as in Mr. Canning.

Political EconomistsAre the most daring of all legislators, just (it has been well said) as "cockney equestrians are the most fearless of all riders." But the confidence with which they propose their theories is less surprising than the facility with which their propositions have been entertained, and their extravagant pretensions admitted. We need not marvel at the success of quackery in medicine and theology, when we look at the career of the St. John Longs in political life. From the time in which the bullion question came out of Pandora's Scotch mull, parliament has been wearied with the interminable discussions which they have raised there. Youths who were fresh from college, and men with or without education, who were "in the wane of their wits and infancy of their discretion," imbibe the radiant darkness of Jeremy Bentham, and forthwith set themselves up as the lights of their generation. No professors, even in the subtlest ages of scholastic philosophy, were ever more successful in muddying what they found clear, and perplexing what is in itself intelligible. What are wages?—this, we are told, is the most difficult and the most important of all the branches of political economy, and this, we are also told, has been obscured by ambiguities and fallacies. What is rent? What is value? Upon these questions, and such as these, which no man of sincere understanding ever proposed to himself or others, they discuss and dilate with as much ardour and to as little effect, as the old philosophers disputed upon the elements of the material creation; bringing to the discussion intellects of the same kind, though as far below them in degree as in the dignity of the subjects upon which their useless subtlety is expended. But it cannot be said of them, that they, when all is said,