Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 367, April 25, 1829

The church of Falkirk was founded in 1057, by Malcolm Canmore, but rebuilt in 1809. In the churchyard are the graves of Sir John Graham and Sir John Stewart, both of whom were killed in 1298, when Edward I. obtained the famous victory over the Scots, under Sir W. Wallace. The battle took place halfway between Falkirk and the river Carron. A stone, called Wallace's Stone, denotes the spot which his division occupied previous to the contest. The tomb of Sir J. Graham bears an inscription. Here also is the monument of Sir R. Munro, who was killed in 1746, when General Hawley was defeated by the Pretender. The scene of this second battle was the Moor of Falkirk, about a mile S.W. of the town.

Immense Plane TreeAt Kippenross is an immense plane tree. It is 27 feet in circumference at the ground, and 30 at the part from which the branches shoot out.

Environs of CallanderThe vicinity of Callander is famous as the scene of Sir W. Scott's "Lady of the Lake." The prospects are beautiful, and there are several objects worthy of being visited. On the banks of the Teith, about a quarter of a mile below the village is the Camp, a villa supposed to occupy the site of a Roman intrenchment. Hence there is a magnificent prospect of Ben Ledi, which rises 3,000 feet above the level of the sea, and bounds the horizon to the N.W. Its name signifies Hill of God, and it is probable that it was formerly the scene of Druidical rites. According to tradition, it was held sacred by the inhabitants of the surrounding country, who annually assembled on the first of May to kindle the sacred fire in honour of the sun, on its summit. Near the summit of Ben Ledi is a small lake, called Loch-au-nan Corp, the Lake of Dead Bodies, a name which it derived from an accident which happened to a funeral here. The lake was frozen and covered with snow; and when the funeral was crossing it, the ice gave way, and all the attendants perished.

About a mile N.E. of Callander is Bracklin Bridge, a rustic work only three feet broad, thrown across a deep chasm, along the bottom of which rolls the river Keltie. The torrent, after making several successive cataracts, at length falls in one sheet about 50 feet in height, presenting from the bridge an appalling spectacle.

Another curiosity near Callander is the Pass of Leney, a narrow ravine, skirted with woods, and hemmed in with rocks, through which a stream, issuing from Loch Lubnaig, rushes with amazing force, forming a series of cascades.

LinlithgowThe palace, which forms the chief object of curiosity in Linlithgow, is a majestic ruin, situated on the margin of a beautiful lake, and covering more than an acre. It is entered by a detached archway, on which were formerly sculptured the four orders borne by James V., the Thistle, Garter, Holy Ghost, and Golden Fleece; but these are now nearly effaced. The palace itself is a massive quadrangular edifice of polished stone, the greater part being five stories in height. A plain archway leads to the interior court, in the centre of which are the ruins of the well.

The west side of the quadrangle, which is the most ancient, was originally built and inhabited by Edward I., and is also interesting as the birth-place of Queen Mary. The room in which she first saw the light is on the second story. Her father, James V., then dying of a broken heart at Falkland, on account of the disaster at Solway Frith, prophetically exclaimed, "It came with a lass," alluding to his family having obtained the crown by marriage, "and it will go with a lass."

The east side, begun by James III., and completed by James V., contains the Parliament Hall. This was formerly the front of the palace, and the porch was adorned with a statue of Pope Julius II., who presented James V. with a consecrated sword and helmet for his resistance to the Reformation. This statue escaped the iconoclastic zeal of the Reformers; but at the beginning of the last century was destroyed by a blacksmith, whose anger against the Papal power had been excited by a sermon.

On an inn-window at Tarbet, in Dunbartonshire, is perhaps the longest specimen of brittle rhymes ever written. They are signed "Thomas Russell, Oct. 3, 1771," and extend to thirty-six lines, being a poetical description of the ascent to Ben Lomond. What would Dr. Watts have said to such a string of inn-window rhymes!

OssianThe principal curiosity in the environs of Dunkeld is the Cascade of the Bran at Ossian's Hall, about a mile distant. This hermitage, or summer-house, is placed on the top of a perpendicular cliff, 40 feet above the bottom of the fall, and is so constructed, that the stranger, in approaching the cascade, is entirely ignorant of his vicinity to it. Upon entering the building is seen a painting, representing Ossian playing on his harp, and singing to a group of females; beside him is his hunting spear, bow and quiver, and his dog Bran. This picture suddenly disappears, and the whole cataract foams at once before you, reflected in several mirrors, and roaring with the noise of thunder. A spectacle more striking it is hardly possible to conceive. The stream is compressed within a small space, and at the bottom of the fall has hollowed out a deep abyss, in which its waters are driven round with great velocity. A little below the hall is a simple arch thrown across the chasm of the rocks, and hence there is a good view of the fall.

Half a mile further up the Bran is Ossian's Cave, part of which has been artificially made; and about a mile higher is the Rumbling Bridge, thrown across a chasm of granite about 15 feet wide. The river for several hundred feet above the arch is crowded with massive fragments of rock, over which it foams and roars; and, approaching the bridge, precipitates itself with great fury through the chasm, making a fall of nearly 50 feet.

Returning to Ossian's Hall, the tourist may continue his excursion along the face of Craig Vinean, the summit of which commands one of the finest prospects in this vicinity. Hence he may form some idea of the extent to which the Duke of Atholl has carried his system of planting. His Grace is said to have planted more than thirty millions of trees in the neighbourhood of Dunkeld.

Loch KatrineWe need scarcely remind the tourist, that the scene of Sir Walter Scott's "Lady of the Lake" is laid in this spot. The following description is from the pen of Dr. Graham, the minister of the parish:—"When you enter the Trosachs there is such an assemblage of wildness and of rude grandeur, as fills the mind with the most sublime conceptions. It seems as if a whole mountain had been torn in pieces, and frittered down by a convulsion of the earth, and the huge fragments of rocks, woods, and hills scattered in confusion at the east end, and on the sides of Loch Katrine. The access to the lake is through a narrow pass of half a mile in length. The rocks are of stupendous height, and seem ready to close above the traveller's head, and to fall down and bury him in the ruins. A huge column of these rocks was, some years ago, torn with lightning, and lies in very large blocks near the road. Where there is any soil, their sides are covered with aged weeping birches, which hang down their venerable locks in waving ringlets, as if to cover the nakedness of the rocks."

"Travellers who wish to see all they can of this singular phenomenon, generally sail westward, on the south side of the lake, to the Rock and Den of the Ghost, whose dark recesses, from their gloomy appearance, the imagination of superstition conceived to be the habitation of supernatural beings. In sailing, you discover many arms of the lake;—here, a bold headland, where black rocks dip into unfathomable water;—there, the white sand in the bottom of a bay, bleached for ages by the waves. In walking on the north side, the road is sometimes cut through the face of a solid rock, which rises upwards of 200 feet perpendicular above the lake. Sometimes the view of the lake is lost, then it bursts suddenly on the eye, and a cluster of islands and capes appear at different distances, which give them an apparent motion, of different degrees of velocity, as the spectator rides along the opposite beach. At other times his road is at the foot of rugged and stupendous cliffs, and trees are growing where no earth is to be seen. Every rock has its echo; every grove is vocal, by the melodious harmony of birds, or by the sweet airs of women and children gathering filberts in their season. Down the side of the mountain, after a shower of rain, flow a hundred white streams, which rush with incredible velocity and noise into the lake, and spread their froth upon its surface. On one side, the water-eagle sits in majesty, undisturbed, on his well-known rock, in sight of his nest, on the face of Ben Venue; the heron stalks among the reeds in search of his prey; and the sportive ducks gambol on the waters or dive below. On the other, the wild goats climb, where they have scarce ground for the soles of their feet; and the wild fowl, perched on the trees, or on the pinnacle of a rock, look down with composed defiance at man. In a word, both by land and water, there are so many turnings and windings, so many heights and hollows, so many glens, capes, and bays, that one cannot advance twenty yards without having the prospect changed by the continual appearance of new objects, while others are retiring out of sight. The scene is closed by a west view of the lake, for several miles, having its sides lined with alternate clumps of wood and arable fields, and the smoke rising in spiral columns through the air from villages which are concealed by the intervening woods; the prospect is bounded by the towering Alps of Arrochar, which are checkered with snow, or hide their heads in the clouds."

"In one of the defiles of the Trosachs, two or three of the natives met a band of Cromwell's soldiers coming to plunder them, and shot one of the party dead, whose grave marks the scene of action, and gives name to the pass. In revenge for this, the soldiers resolved to attack an island in the lake, on which the wives and children of the men had taken refuge. They could not come at it, however, without a boat; one of the most daring of the party undertook to swim to the island and bring away the boat; when, just as he was catching hold of a rock to get ashore, a heroine, called Helen Stuart, met him and cut off his head with a sword; upon which the party, seeing the fate of their comrade, thought proper to withdraw."

Loch Katrine is about ten miles long, and one broad. Its depth in some parts is nearly 500 feet. Its temperature, at the surface, is 62°, and at the bottom 40°. The lake never freezes, and in winter is much resorted to by swans.

PORTRAIT-PAINTING

Painters of history make the dead live, and do not live themselves till they are dead, I paint the living, and they make me live.—Sir Godfrey Kneller.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

PRACTICE OF COOKERY,

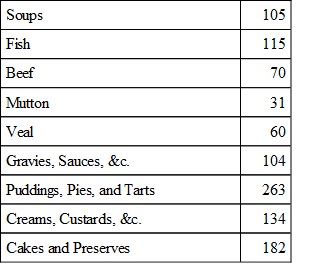

Adapted to the Business of every day Life. By Mrs. DalgairnsWe like the title of this book—there is promise in it, for practice is better than profession in any thing but the law of arrest. We are gross enough too, in our hearts, not to like the name of a professed cook—thank our stars, now nearly forgotten. There is so much science implied in the name, so much theory, than which alone in cookery, at least, nothing is less inviting. We should conceive the intention of this book to bring cookery home to the business of every man's mouth—his breakfast, luncheon, dinner, and supper practice, and heartily do we wish that all mankind were in a condition to avail themselves of these four quotidian opportunities of testing Mrs. Dalgairns's book.

"A perfectly original book of Cookery," says Mrs. D. "would neither meet with, nor deserve, much attention; because, what is wanted in this matter, is not receipts for new dishes, but clear instructions how to make those already established in public favour." This reasoning is very just, for none but the most thankless of gourmands, or the gourmet who wished to affect the sorrows of the great man of antiquity,—would sit down and weep for new worlds of luxury. Good cookery is too rarely understood and practised to justify any such wishes; and to prove this, let the sceptic go through Mrs. Dalgairns's 1,434 receipts, and then "tire and begin again." Our respected editress assures us that "every receipt has either been actually tried by the author, or by persons whose accuracy in the various manipulations3 could be safely relied on."

From a table of contents we learn that among them there are the following methods:—

—what more can mortal man desire, "nay, or women either." Appended to them is much valuable information concerning the poultry-yard, dairy, brewery, kitchen-garden, bees, pigs, &c. so as to render this Practice of Cookery a truly useful and treasurable system of domestic management, and a book of matters-of-fact and experience. The subject is too melting—too tempting for us to resist paying this tribute to Mrs. Dalgairns's volume.

"CLOUDS AND SUNSHINE."

An appropriate April book, too controversial for extensive quotation in our pages, as the enumeration of its contents will prove. They are half-a-dozen gracefully written sketches, viz. the Gipsy Girl, Religious Offices, Enthusiasm, Romanism, Rashness, and De Lawrence. Half of these papers, as will readily be guessed from their titles, bear upon "the question," and are consequently, as the publishers say, "not in our way." We are, nevertheless, proud to aver that the sentiments of these chapters are highly honourable to the heart of the writer as they are creditable to his good taste and ability. He is, to judge from his book, a good man, one who is not so willing as the majority of us, to let his philanthropy remain

"Like unscour'd armour, hung by the wall;"and we hope the forcible positions of the truths he has here inculcated, will bestir others from their laxity. The most attractive sketches in the series are the Gipsy Girl and De Lawrence. In the latter there are scenes of considerable energy and polish. The hero, a profligate, after abusing all the advantages of fortune, commits a forgery, and is executed. The sympathies of an affectionate wife, in his misery and degradation, tend to heighten the interest, and point the moral of the story; his last interview with the partner of his woe is admirably drawn, as are some caustic observations on that most disgusting of all scenes—a public execution and its repulsive orgies. We give a portion of the interview, which appears to us to contain some fine touches of deep remorse:—

"Accompanied by her parents and her infant, she alighted at the tavern which adjoined the prison-house. Her father went immediately to arrange for the interview; which, as the time of execution drew nigh, must take place instantly or not at all. Habited in deep black, which, from the contrast, made the pale primrose of her cheek still paler, entered his drooping wife; bearing on her bosom, "cradled on her arm," their child, happily unconscious alike of its father's ignominy—its mother's sorrows. With uncertain steps she tottered towards him. He advanced to her embrace, at first, with coolness and deliberation; but when her altered look, on which care had engraven an accusation that smote with the chill of death his guilty heart—her lack-lustre eye—her form almost reduced to a shadow—met his glance, his resolution dissolved before them: the better feelings of his nature, long lulled by habitual vice, and fixed in inertion by the flattering commendations of his spiritual guide, burst forth afresh like a stream long pent up, and overwhelmed him with their gush. He sank upon one knee, and received his wife and child falling into his embrace. His haughty spirit was humbled, was softened. He could have borne her curses with indifference, he could have returned a formal adieu with equal formality—he had expected to encounter a scene, and was made up accordingly: but to look upon her thus—her days gone like a shadow—to witness her sunken eye filled with beamings in which he alone was enshrined—to see her meek and forgiving, whose light heart had been turned to sorrow, whose gay morning dreams had been turned to sad realities, whose confidence had been abused and happiness wrecked,—all, all by his baseness and treachery:—to behold his forsaken wife, superior to all this, clinging to him for his last farewell, as if she and not himself were the offender, was beyond his expectation. He knew he had merited curses and hate, and he met with affection and tenderness; his heart yearned—a sensation of admiration for her virtues and constancy came over him, and, ere it had possessed him entirely, it humbled his proud spirit—it undeceived his false expectations. "My God, I have not deserved this!" burst from his swelling heart. A tear, such as he had not shed since he left the paths of innocence, stole down his cheek. Fervently, truly, affectionately, he blessed his wife and child."

"They are gone. Was it a vision that had visited his waking dreams? The spell is dissolved; he is still on earth, and earthly thoughts and worldly crimes return and weigh down his soul."

"The fetters of vice are not broken in a moment; they may yield sometimes like wax, but they close again, and the link is adamant. His foster-mother came to say her last farewell. He shuddered as she entered. He felt the presence of his evil genius, and wished she had spared him this. This, too, was transient; her influence, though disarranged by the vision of the last few moments, was not broken. He was again enslaved. The summons for execution was answered by her hysteric sobs and wild ravings, and her loud shrieks rang through the cell as De Lawrence impressed his last kiss."

The incidents of the previous sketch contain little, if any, extravagance or affectation, and it would be better for men, if we could charge the author of "Clouds and Sunshine" with overcolouring the sufferings which await the spendthrift. It is painful to own that such cases are but too common in society. Think of an extravagant man married to an extravagant woman—the mean and contemptible conduct to which they are driven—the insolence and cruelty with which they are baited through large towns, hunted down into an obscure cottage in the country, or chased into exile. Think of the hateful reflections which, sooner or later, must overtake such sufferers—either in their moody solitude in the country, or amidst the forced delights of a crowded city on the continent. In the one all nature is free, whilst the debauchee frowns on her laughing landscapes; in the other, conscience and her busy devils are at work—yet thousands thus embitter life's cup, and then repine at their uncheery lot. With such men, all must be Clouds—a winter of discontent—for who will envy their Sunshine.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

NOSES

Observations on the Organ of ScentBy William Wadd, Esq., F.L.S"Non cuicunque datum est habere nasum."—Martial.

"I have a nose."—Proby.

It has often struck me as a defect in our anatomical teachers, that in describing that prominent feature of the human face, the organ of scent, they generalize too much, and have but one term for the symmetrical arch, arising majestically, or the tiny atom, scarcely equal to the weight of a barnacle—a very dot of flesh! Nor is the dissimilarity between the invisible functions of the organ, and the visible varieties of its external structure, less worthy of remark. With some, the sense of smelling is so dull, as not to distinguish hyacinths from assafoetida; they would even pass the Small-Pox Hospital, and Maiden-lane, without noticing the knackers; whilst others, detecting instantly the slightest particle of offensive matter, hurry past the apothecaries, and get into an agony of sternutation, at fifty yards from Fribourg's.

Shakspeare, who was a minute observer of the anatomical and physiological varieties of the human frame, did not allow this dissimilarity to pass unnoticed; and, moreover, he starts a query that has never been satisfactorily answered, from his time to the present; viz. "Canst thou tell why one's nose stands i' the middle of one's face?"4 And his nice discrimination about noses extends also to shape and colour.—from the "Red-nosed innkeeper of Dav'ntry,"5 and the "Malmsy-nosed knave, Bardolph,"6 to him in Henry V., "whose nose was sharp as a pen!"

This celebrated "Malmsy-nose" possessed properties unknown to the same feature now-a-days. It was adapted to practical utility, in its application to domestic purposes, and moral instruction, by that great admirer and competent judge of its virtues, Sir John Falstaff, to whose sheets it did the office of a warming-pan;7 and who made as good use of it as some men do of a death's head, or a memento mori: "I never see it," said he, "but I think upon hell fire." It stands almost unrivalled in history, and ranks at least with that which gave a cognomen to Ovid,8 and the one to which the celebrated violoncello player, Cervetto, owed the sobriquet of Nosey. This epithet reminds me of another nose of theatrical notoriety, whose rubicund tint, when it interfered with the costume of a sober character which its owner was enacting, was moderated by his wife, who, with laudable anxiety to keep down its "rosy hue," was constantly behind the scenes with a powder puff, which she was accustomed to apply, ejaculating, "'Od rot it, George! how you do rub your poor nose! Come here, and let me powder it. Do you think Alexander the Great had such a nose?"

Nor would I omit to mention one, contemporary almost with the above, by which the public peace was said to be endangered, as recorded by a poet of the day, who states,–

"Amongst the crowds, not one in tenEre saw a thing so rare;Its size surpriseth all the men,Its charms attract the fair.'Tis wonderful to see the folk,Who at the nose do gaze;All grin and laugh, and sneer and joke,And gape in such amaze.The children, whom the sight doth please,Their little fingers point;Wishing to give it one good squeeze,And pull it out of joint."Much more is said by the poet in its praise; at last he falls into a moral strain:

"For many, as you may suppose,'Gainst nature loudly bawl,—That one man should have such a nose,Whilst some have none at all."And then concludes with some excellent sentiments:—

"Though ev'ry man's a nat'ral rightTo shew a moderate nose,Yet surely 'tis a piece of spiteTo spoil the world's repose.'Tis wrong t' exhibit such a show,Though you may think it funYet still, good Sir, you little knowWhat evil it has done.What quarrels have from hence begun!What anger and what strife!What blows have pass'd 'tween man and man!What kicks 'tween man and wife!No longer, then, thyself disgrace,In quest of beauty's fame;No longer, then, expose thy face,To get thy nose a name.Take it away, if thou art wise,And keep it safe at home,Amongst thy curiositiesOf ancient Greece and Rome."Shakspeare would have thought it high treason, for he says,—

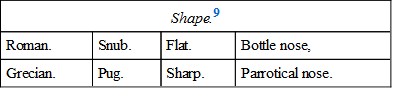

"Down with the nose, take the bridge quite awayOf him, that his particular to forefendSmells from the general weal."There may have been many other such noses that have escaped observation,—"born to blush unseen:" enough, however, I have here stated of those my recollection furnishes me with at the moment, to establish the fact of variety, and to lead curious physiologists to a scientific classification of this prominent and well-deserving feature of the human face. I would recommend a proper distinction being observed between functional varieties, and those which arise from size, shape, or colour, of which, in a cursory way, may be enumerated first,—

9Lavater considers the nose as the fulcrum of the brain; and describes it as a piece of Gothic architecture. "It is in the nose that the arch of the forehead properly rests, the weight of which, but for this, would mercilessly crush the cheeks and the mouth." He enters into the philosophy of noses with diverting enthusiasm, and finally concludes, "Non cuique datum est habere nasum:"—it is not every one's good fortune to have a nose! A sharp nose has been considered the visible mark of a shrew.