Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829

We were near enough to distinguish the Turkish and Egyptian sailors in the enemy's ships. They seemed to be a motley group. Most of them wore turbans of white, with a red cap below, small brown jackets, and very wide trousers; their legs were bare. They were active, brawny fellows, of a dark-brown complexion, and they crowded the Turkish ships, which accounts for the very great slaughter we occasioned among them. Many dead bodies were tumbled through their port-holes into the sea.

Capt. Hugon, commanding the French frigate L'Armide, about three o'clock, seeing the unequal, but unflinching combat we were maintaining, wormed his ship coolly and deliberately through the Turkish inner line, in such a gallant, masterly style, as never for one moment to obstruct the fire of our ship upon our opponents. He then anchored on our starboard-quarter, and fired a broadside into one of the Turkish frigates, thus relieving us of one of our foes, which, in about ten minutes, struck to the gallant Frenchman; who, on taking possession, in the most handsome manner, hoisted our flag along with his own, to show he had but completed the work we had begun. The skill, gallantry, and courtesy of the French captain, were the subject of much talk amongst us, and we were loud in his praise. We had still two of the frigates and the corvette to contend with, whilst the Armide was engaged, when a Russian line-of-battle-ship came up, and attracted the attention of another Egyptian frigate, and thus drew off her fire from us. Our men had now a breathing time, and they poured broadside upon broadside into the Egyptian frigate, which had been our first assailant. The rapidity and intensity of our concentrated fire soon told upon the vessel. Her guns were irregularly served, and many shots struck our rigging. Our round-shot, which were pointed to sink her, passed through her sides, and frequently tore up her decks in rebounding. In a short time she was compelled to haul down her colours, and ceased firing. We learned afterwards, that her decks were covered with nearly one hundred and fifty dead and wounded men, and the deck itself ripped up from the effects of our balls. In the interim, the corvette, which had annoyed us exceedingly during the action, came in for her share of our notice, and we managed to repay her in some style for the favours she had bestowed on us in the heat of the business. Orders were then issued for the men to cease firing for a few minutes, until the Rose had passed between our ship and the corvette, and had stationed herself in such a position as to annoy the latter in conjunction with us. Our firing was then renewed with redoubled fury, The men, during the pause, had leisure to quench their thirst from the tank which stood on the deck, and they appeared greatly refreshed—I may say, almost exhilarated, and to their work they merrily went again.

The double-banked Egyptian frigate, which had struck her colours to us, to our astonishment began, after having been silenced for some time, to open a smart fire on our ships, though she had no colours flying. The men were exceedingly exasperated at such treacherous conduct, and they poured into her two severe broadsides, which effectually silenced her, and at the moment we saw that a blue ensign was run up her mast, on which we ceased cannonading her, and she never fired another gun during the remainder of the action. It was a Greek pilot, pressed on board the Egyptian, who ran up the English ensign, to prevent our ship from firing again. He declared that our shot came into the frigate as thick and rapidly as a hail-storm, and so terrified the crew, that they all ran below. From the combined effects of our firing, and that of the Russian ship, the other Egyptian frigate hauled down her colours. The corvette, which was roughly handled by the Rose, was driven on shore, and there destroyed.

Before this, however, a Turkish fireship approached us, having seemingly no one on board. We fired into her, and in a few minutes she loudly exploded astern, without doing us any damage. The concussion was tremendous, shaking the ship through every beam. Another fireship came close to the Philomel which soon sunk her, and in the very act of going down she exploded.

A large ship near the Asia was now seen to be on fire; the blaze flamed up as high as the topmast, and soon became one vast sheet of fire; in that state she continued for a short time. The crew could be easily discerned gliding about across the light; and, after a horrible suspense, she blew up, with an explosion far louder and more stunning than the ships which had done so in our vicinity. The smoke and lurid flame ascended to a vast height in the air; beams, masts, and pieces of the hull, along with human figures in various distorted postures, were clearly distinguishable in the air.

It was now almost dark, and the action had ceased to be general throughout the lines; but blaze rose upon blaze, and explosion thundered upon explosion, in various parts of the bay. A pretty sharp cannonading had been kept up between the guns of the castle and the ships entering the bay, and that firing still continued. The smaller Turkish vessels, forming the second line, were now nearly silenced, and several exhibited signs of being on fire, from the thick light-coloured smoke that rose from their decks.

The action had nearly terminated by six o'clock, after a duration of four hours. Daylight had disappeared unperceived, owing to the dense smoke of the cannonading, which, from the cessation of the firing, now began to clear away, and showed us a clouded sky. The bay was illuminated in various quarters by the numerous burning ships, which rendered the sight one of the most sublime and magnificent that could be imagined.

MEMORABLE DAYS

VALENTINE'S DAY

Seynte Valentine. Of custome, yeere by yeere,Men have an usaunce, in this regioun,To loke and serche Cupide's kalendere,And chose theyr choyse, by grete affeccioun;Such as ben move with Cupide's mocioun,Taking theyr choyse as theyr sorte doth falle;But I love oon whyche excellith alle.LYDGATE'S Poem of Queen Catherine, consort to Henry V., 1440In some villages in Kent there is a singular custom observed on St. Valentine's day. The young maidens, from five or six to eighteen years of age, assemble in a crowd, and burn an uncouth effigy, which they denominate a "holly boy," and which they obtain from the boys; while in another part of the village the boys burn an equally ridiculous effigy, which they call an "ivy girl," and which they steal from the girls. The oldest inhabitants can give you no reason or account of this curious practice, though it is always a sport at this season.

Numerous are the sports and superstitions concerning the day in different parts of England. In some parts of Dorsetshire the young folks purchase wax candles, and let them remain lighted all night in the bedroom. I learned this from some old Dorsetshire friends of mine, who, however, could throw no further light upon the subject. In the same county, I was also informed it was in many places customary for the maids to hang up in the kitchen a bunch of such flowers as were then in season, neatly suspended by a true lover's knot of blue riband. These innocent doings are prevalent in other parts of England, and elsewhere.

Misson, a learned traveller, relates an amusing practice which was kept up in his time:—"On the eve of St. Valentine's day, the young folks in England and Scotland, by a very ancient custom, celebrated a little festival. An equal number of maids and bachelors assemble together; all write their true or some feigned name separately upon as many billets, which they rolled up, and drew by way of lots, the maids taking the men's billets, and the men the maids'; so that each of the young men lights upon a girl that he calls his Valentine, and each of the girls upon a young man which she calls her's. By this means each has two Valentines; but the man sticks faster to the Valentine that falls to him, than to the Valentine to whom he has fallen. Fortune having thus divided the company into so many couples, the Valentines give balls and treats to their fair mistresses, wear their billets several days upon their bosoms or sleeves, and this little sport often ends in love."

In Poor Robin's Almanack, 1676, the drawing of Valentines is thus alluded to:

"Now Andrew, Antho-Ny, and William,For Valentines drawPrue, Kate, Jilian."Gay makes mention of a method of choosing Valentines in his time, viz. that the lad's Valentine was the first lass he spied in the morning, who was not an inmate of the house; and the lass's Valentine was the first young man she met.

Also, it is a belief among certain playful damsels, that if they pin four bay leaves to the corners of the pillow, and the fifth in the middle, they are certain of dreaming of their lover.

Shakspeare bears witness to the custom of looking out of window for a Valentine, or desiring to be one, by making Ophelia sing:—

Good morrow! 'tis St. Valentine's day,All in the morning betime,And I a maid at your window.To be your Valentine!In London this day is ushered in by the thundering knock of the postman at the different doors, through whose hands some thousands of Valentines pass for many a fair maiden in the course of the day. Valentines are, however, getting very ridiculous, if we may go by the numerous doggrels that appear in the print-shops on this day. As an instance, I transmit the reader a copy of some lines appended to a Valentine sent me last year. Under the figure of a shoemaker, with a head thrice the size of his body, and his legs forming an oval, were the following rhymes:—

Do you think to be my Valentine?Oh, no! you snob, you shan't be mine:So big your ugly head has grown,No wig will fit to seem your ownGo, find your equal if you can,For I will ne'er have such a man;Your fine bow legs and turned-in feet,Make you a citizen complete."The fair writer had here evidently ventured upon a pun; how far it has succeeded I will leave others to say. The lovely creature was, however, entirely ignorant of my calling; and whatever impression such a description would leave on the reader's mind, it made none on mine, though in the second verse I was certainly much pleased with the fair punster. I wish you saw the engraving!

W.H.H

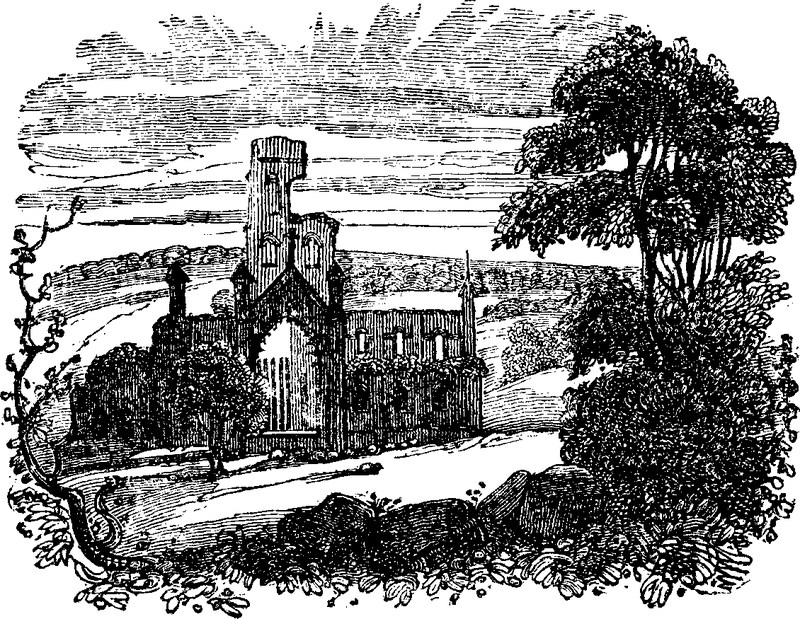

The first page or frontispiece embellisment of the present Number of the MIRROR illustrates one of the most recent triumphs of art; and the above vignette is a fragment of the monastic splendour of the twelfth century. Truly this is the bathos of art. The plaster and paint of the Colosseum are scarcely dry, and half the work is in embryo; whilst Kirkstall is crumbling to dust, and reading us "sermons in stones:" we may well say,

"Look here, upon this picture, and on this."Kirkstall Abbey is situated a short distance from Leeds, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Its situation is one of the most picturesque that the children of romance can wish for, being in a beautiful vale, watered by the river Aire. It was of the Cistercian order, founded by Henry de Lacy in 1157, and valued at the dissolution at 329l. 2s. 11d. Its rents are now worth 10,253l. 6s. 8d. The gateway has been walled up, and converted into a farm-house. The abbot's palace was on the south; the roof of the aisle is entirely gone; places for six altars, three on each side the high altar, appear by distinct chapels, but to what saints dedicated is not easy, at this time, to discover. The length of the church, from east to west, was 224 feet; the transept, from north to south, 118 feet. The tower, built in the time of Henry VIII., remained entire till January 27, 1779, when three sides of it were blown down, and only the fourth remains. Part of an arched chamber, leading to the cemetery, and part of the dormitory, still remain. On the ceiling of a room in the gatehouse is inscribed,

Mille et Quingentos postquam compleverit OrbisTuq: et ter demos per sua signi DeusPrima sauluteferi post cunabula Christi,Cui datur omnium Honor, Gloria, Laus, et Amor.The principal window is particularly admired as a rich specimen of Gothic beauty, and a tourist, in 1818, says, "bids defiance to time and tempest;" but in our engraving, which is of very recent date, the details of the window will be sought for in vain. "Shrubs and trees," observes the same writer, "have found a footing in the crevices, and branches from the walls shook in undulating monotony, and with a gloomy and spiritual murmur, that spoke to the ear of time and events gone by, and lost in oblivion and dilapidation. At the end, immediately beneath the colossal window, grows an alder of considerable luxuriance, which, added to the situation of every other object, brought Mr. Southey's pathetic ballad of 'Mary the Maid of the Inn,' so forcibly before my imagination,5 that I involuntarily turned my eye to search for the grave, where the murderers concealed their victim." He likewise tells us of "the former garden of the monastery, still cultivated, and exhibiting a fruitful appearance;" cells and cavities covered with underwood; and his ascent to a gallery by a winding turret stair, whence, says he, "the monks of Kirkstall feasted their eyes with all that was charming in nature. It is said," adds he, "that a subterraneous passage existed from hence to Eshelt Hall, a distance of some miles, and that the entrance is yet traced."

THE NATURALIST

AMERICAN SONG BIRDS

The Mocking-bird seems to be the prince of all song birds, being altogether unrivalled in the extent and variety of his vocal powers; and, besides the fulness and melody of his original notes, he has the faculty of imitating the notes of all other birds, from the humming-bird to the eagle. Pennant tells us that he heard a caged one, in England, imitate the mewing of a cat and the creaking of a sign in high winds. The Hon. Daines Barrington says, his pipe comes nearest to the nightingale, of any bird he ever heard. The description, however, given by Wilson, in his own inimitable manner, as far excels Pennant and Barrington as the bird excels his fellow-songsters. Wilson tells that the ease, elegance and rapidity of his movements, the animation of his eye, and the intelligence he displays in listening and laying up lessons, mark the peculiarity of his genius. His voice is full, strong, and musical, and capable of almost every modulation, from the clear mellow tones of the wood thrush to the savage scream of the bald eagle. In measure and accents he faithfully follows his originals, while in force and sweetness of expression he greatly improves upon them. In his native woods, upon a dewy morning, his song rises above every competitor, for the others seem merely as inferior accompaniments. His own notes are bold and full, and varied seemingly beyond all limits. They consist of short expressions of two, three, or at most five or six, syllables, generally expressed with great emphasis and rapidity, and continued with undiminished ardour, for half an hour or an hour at a time. While singing, he expands his wings and his tail, glistening with white, keeping time to his own music, and the buoyant gaiety of his action is no less fascinating than his song. He sweeps round with enthusiastic ecstasy, he mounts and descends as his song swells or dies away; he bounds aloft, as Bartram says, with the celerity of an arrow, as if to recover or recall his very soul, expired in the last elevated strain. A bystander might suppose that the whole feathered tribes had assembled together on a trial of skill; each striving to produce his utmost effect, so perfect are his imitations. He often deceives the sportsman, and even birds themselves are sometimes imposed upon by this admirable mimic. In confinement he loses little of the power or energy of his song. He whistles for the dog; Cæsar starts up, wags his tail, and runs to meet his master. He cries like a hurt chicken, and the hen hurries about, with feathers on end, to protect her injured brood. He repeats the tune taught him, though it be of considerable length, with great accuracy. He runs over the notes of the canary, and of the red bird, with such superior execution and effect, that the mortified songsters confess his triumph by their silence. His fondness for variety, some suppose to injure his song. His imitations of the brown thrush is often interrupted by the crowing of cocks; and his exquisite warblings after the blue bird, are mingled with the screaming of swallows, or the cackling of hens. During moonlight, both in the wild and tame state, he sings the whole night long. The hunters, in their night excursions, know that the moon is rising the instant they begin to hear his delightful solo. After Shakspeare, Barrington attributes in part the exquisiteness of the nightingale's song to the silence of the night; but if so, what are we to think of the bird which in the open glare of day, overpowers and often silences all competition? His natural notes partake of a character similar to those of the brown thrush, but they are more sweet, more expressive, more varied, and uttered with greater rapidity.

The Yellow breasted Chat naturally follows his superior in the art of mimicry. When his haunt is approached, he scolds the passenger in a great variety of odd and uncouth monosyllables, difficult to describe, but easily imitated so as to deceive the bird himself, and draw him after you to a good distance. At first are heard short notes like the whistling of a duck's wings, beginning loud and rapid, and becoming lower and slower, till they end in detached notes. There succeeds something like the barking of young puppies, followed by a variety of guttural sounds, and ending like the mewing of a cat, but much hoarser.

The song of the Baltimore Oriole is little less remarkable than his fine appearance, and the ingenuity with which he builds his nest. His notes consist of a clear mellow whistle, repeated at short intervals as he gleams among the branches. There is in it a certain wild plaintiveness and naïveté extremely interesting. It is not uttered with rapidity, but with the pleasing tranquillity of a careless ploughboy, whistling for amusement. Since the streets of some of the American towns have been planted with Lombardy poplars, the orioles are constant visiters, chanting their native "wood notes wild," amid the din of coaches, wheelbarrows, and sometimes within a few yards of a bawling oysterwoman.

The Virginian Nightingale, Red Bird, or Cardinal Grosbeak, has great clearness, variety, and melody in his notes, many of which resemble the higher notes of a fife, and are nearly as loud. He sings from March till September, and begins early in the dawn, and repeating a favourite stanza twenty or thirty times successively, and often for a whole morning together, till, like a good story too frequently repeated, it becomes quite tiresome. He is very sprightly, and full of vivacity; yet his notes are much inferior to those of the wood, or even of the brown thrush.

The whole song of the Black-throated Bunting consists of five, or rather two, notes; the first repeated twice and very slowly, the third thrice and rapidly, resembling chip, chip, che-che-che; of which ditty he is by no means parsimonious, but will continue it for hours successively. His manners are much like those of the European yellow-hammer, sitting, while he sings, on palings and low bushes.

The song of the Rice Bird is highly musical. Mounting and hovering on the wing, at a small height above the ground, he chants out a jingling melody of varied notes, as if half a dozen birds were singing together. Some idea may be formed of it, by striking the high keys of a piano-forte singly and quickly, making as many contrasts as possible, of high and low notes. Many of the tones are delightful, but the ear can with difficulty separate them. The general effect of the whole is good; and when ten or twelve are singing on the same tree, the concert is singularly pleasing.

The Red-eyed Flycatcher has a loud, lively, and energetic song, which is continued sometimes for an hour without intermission. The notes are, in short emphatic bars of two, three, or four syllables. On listening to this bird, in his full ardour of song, it requires but little imagination to fancy you hear the words "Tom Kelly! whip! Tom Kelly!'" very distinctly; and hence Tom Kelly is the name given to the bird in the West Indies.

The Crested Titmouse possesses a remarkable variety in the tones of its voice, at one time not louder than the squeaking of a mouse, and in a moment after whistling aloud and clearly, as if calling a dog, and continuing this dog-call through the woods for half an hour at a time.

The Red-breasted Blue Bird has a soft, agreeable, and often repeated warble, uttered with opening and quivering wings. In his courtship he uses the tenderest expressions, and caresses his mate by sitting close by her, and singing his most endearing warblings. If a rival appears, he attacks him with fury, and having driven him away, returns to pour out a song of triumph. In autumn his song changes to a simple plaintive note, which is heard in open weather all winter, though in severe weather the bird is never to be seen.—Mag. Nat. Hist.

THE JOHN DORY

In the 312th Number of the Mirror, several solutions are given of the name of a well-known and high-priced fish, the John Dory, or Jaune Dorée. Sir Joseph Banks's observation, that it should be spelled and acknowledged "adorée," because it is the most valuable (or worshipful) of fish, as requiring no sauce, is equally absurd and unwarranted; for so far from its being incapable of improvement from such adjuncts, its relish is materially augmented by any one of the three most usual side tureens. The dory attains its fullest growth in the Adriatic, and is a favourite dish in Venice, where, as in all the Italian ports of the Mediterranean, it is called Janitore, or the gate-keeper, by which title St. Peter is most commonly designated among the Catholics, as being the reputed keeper of the keys of heaven. In this respect, the name tallies with the superstitious legend of this being the fish out of whose mouth the apostle took the tribute money. The breast of the animal is very much flattened, as if it had been compressed; but, unfortunately for the credit of the monks, this feature is exhibited in equally strong lineaments by, at least, twenty other varieties of the finny tribe.

Our sailors naturally substituted the appellation of John Dory for the Italian Janitore, and a very high price is sometimes given for this fish when in prime condition, as I can testify from experience; having two years since seen one at Ramsgate which was sold early in the day for eighteen shillings.

JOHNNY RAWTHE SELECTOR, AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

"Anecdotes correspond in literature with the sauces, the savoury dishes, and the sweetmeats of a splendid banquet;" and as our weekly sheet is a sort of literary fricassee, the following may not be unacceptable to the reader. They are penciled from a work quaintly enough entitled "The Living and the Dead, by a Country Curate;" and equally strange, the cognomen of the author is not a ruse—he being a curate at Liverpool, the son of Dr. Adam Neale, and a nephew of the late Mr. Archibald Constable, the eminent publisher, of Edinburgh. The information which this volume contains, may therefore be received with greater confidence than is usually attached to flying anecdotes; since Mr. Constable's frequent and familiar intercourse with the first literary characters of his time must have given him peculiar facilities of observation of their personal habits. The present volume of "The Living and the Dead" is what the publisher terms the Second Series; for, like Buck, the turncoat actor, booksellers always think that one good turn deserves another. Our first extracts relate to Chantrey's monument in Lichfield Cathedral, and another of rival celebrity.

At the retired church of Ashbourne is "a remarkable monument", by Banks, to the memory of a very lovely and intelligent little girl, a baronet's only child. It bears an inscription which, to use the mildest term, as it contains not the slightest reference to Christian hopes, should have been refused admittance within a Christian church. To the sentiments it breathes, Paine himself, had he been alive, could have raised no objection. * * * * The figure, which is recumbent, is that of a little girl; the attitude exquisitely natural and graceful. It recalls most forcibly to the recollection Chantrey's far-famed monument in Lichfield Cathedral; for the resemblance, both in design and execution, between these beautiful specimens of art is close and striking.