Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829

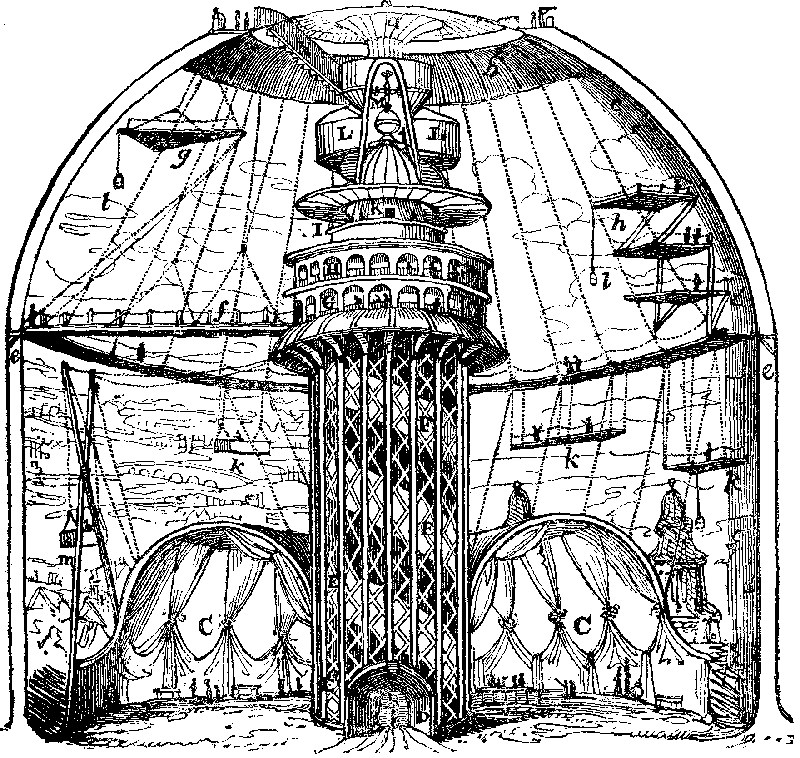

Interior of the Colosseum

References to the Engraving.

A. Column or Tower in the centre of the building, for supporting the Ascending Room, &c.

B. Entrance to the Ascending-Room.

C. Saloon for the reception of works of art.

D. Passage lending to the Saloon, Galleries, and Ascending-Room.

E. F. Two separate Spiral Flights of Steps, leading to the Galleries, &c.

G. H. I. Galleries from which the Picture is to be viewed.

K. Refreshment-Room.

L. Rooms for Music or Bells.

M. The Old Ball from St. Paul's Cathedral.

N. Stairs leading to the outside of the Building. a. b. Sky-lights. c. Plaster Dome, on which the sky is painted, d. Canvass on which the part of the picture up to the horizon is painted. e. Gallery, suspended by ropes, used for painting the distance, and uniting the plaster and the canvas. f. Temporary Bridge from the Gallery G to the Gallery e. from the end of which the echo of the building might be heard to the greatest advantage. g. One of Fifteen Triangular Platforms, used for painting the sky. h. Platforms fixed on the ropes of the Gallery e, used for finishing and clouding the sky. k. Different methods for getting at the lower parts of the canvas. l. Baskets for conveying colours. &c. to the artists, m. Cross or Shears, formed of two poles, from which a cradle or box is suspended, for finishing the picture after the removal of all the scaffolding and ropes.

Mr. Hornor, in his colossal undertaking, has "devised a mean" to draw us out of the way; and a successful one it has already proved. As a return for the interest which his enterprise has excited, we are, however, induced to present its details to our readers, as perfect as the limits of the MIRROR will allow; and for this purpose we have been favoured by Mr. Parris with the drawing for the annexed cut.

In No. 352, we gave a popular description of the interior of the Colosseum; but the reader's attention was therein directed to the splendid effect of the panorama or picture, whilst the means by which the painting was executed have been reserved for our present Number. This we have endeavoured to illustrate by the annexed engraving; and the explanation will be rendered still clearer by reference to No. 352, wherein we have given an outline of the difficulties with which the principal artist, Mr. Parris, had to contend in painting the panorama. We, however, omitted to state an obstacle equally formidable with the reconciliation of the styles of the several artists engaged to assist Mr. Parris. This additional source of perplexity was the great change, almost amounting to the vitrification of enamel colours, which occurred in the hues of the various pigments, according to the point of view, and the immense distance of the canvas from the spectator.

Besides furnishing the reader with the construction of the apartments, galleries, and ascents of the interior, the engraving presents some idea of the scaffoldings, bridges, platforms, and other mechanical contrivances requisite for the execution of the picture.

The spiral staircase, it will be seen, leads to the lower gallery for viewing the picture. Unconnected with the intermediate gallery, there is a communication from the lowest gallery to the highest, and thence to the refreshment-rooms and exterior of the dome. The ascent to the second price gallery is by a spiral staircase under those already mentioned. The column, or central erection, containing these staircases and the ascending-room, is of timber, with twelve principal uprights seventy-three feet high, one foot square, set upon a circular curb of brickwork, hooped with iron, and further secured by bracing, and by two other circular curbs, from the upper one of which rises a cone of timbers thirty-four feet high, supporting the refreshment-rooms, the identical ball, and model of the cross, of St. Paul's, Mr. Hornor's sketching cabin, staircase to the exterior, &c. Without the circle of timbers already described, is another of twenty-four upright timbers; and between these two circles the staircases wind. The architectural fronts of the galleries form frame-works, through which the spectator may enjoy various parts of the panorama, as in so many distinct pictures.

The cut and appended references will explain the devices for painting better than a more extended description; for mere words do not facilitate the understanding of inventions which in themselves are beautiful and simple. To heighten the effect, our artist has, however, introduced light sketchy outlines of the campanile towers of St. Paul's, the city, and the distant country. Mr. Parris's task must have been one of extreme peril, and notwithstanding his ingenious contrivances of galleries, bridges, platforms, &c. he fell twice from a considerable height; but in neither case was he seriously hurt. His progress reminds us of other grand flights to fame, but his success has been triumphant, and alike honourable to his genius and enterprise. In short, looking at the present advanced state of the Colosseum, Mr. Hornor and his indefatigable coadjutors may almost exclaim in the words of Dryden,

"Our toils, my friend, are crown'd with sure success:The greater part perform'd, achieve the less."DORCHESTER

(For the Mirror.)St. Peter's church, Dorchester, is a handsome structure. There is a traditional rhyme about it which imports the founder of this church to have been Geoffery Van.

"Geoffery VanWith his wife AnneAnd his maid NanBuilt this church."But there was long since dug up in a garden here a large seal, with indisputable marks of antiquity, and this inscription:—"Sigillum Galfridi de Ann." It is therefore supposed, with some reason, that the founder's name was Ann.

A great number and variety of Roman coins have been dug up in this town, some of silver, others of copper, called by the common people, King Dorn's Pence; for they have a notion that one king Dorn was the founder of Dorchester.

HALBERT HFIRE AT YORK CATHEDRAL

(For the Mirror.)Ut Rosa flos florumSic est domus ista domorum.Such was the encomium bestowed on the venerable pile of York Minster by an old monkish writer; but, alas! what a change is there in the space of a few short hours; what a scene of desolation, what a lesson of the instability of sublunary things and the vanity of human grandeur! The glory of the city of York, of England, yea, almost of Europe, is now, through the fanaticism of a modern Erostratus, rendered comparatively a pile of ruin; but still

"Looks great in ruin, noble in decay."This is the third time that this magnificent structure has been assailed by fire; twice it has been totally destroyed; but, like another phoenix, it has again risen from its ashes in a greater degree of splendour. A period of nearly seven hundred years has now elapsed since the last of these occurrences; and the present fabric has but now narrowly escaped sharing the fate of its predecessors.

The damage which the Minster has sustained is not, perhaps, of so great a magnitude as, from the first appearance of the fire, might have been anticipated. The destruction is principally confined to the choir, the roof of which is entirely consumed. The beautiful and elaborately carved screen,1 which divides the choir from the nave, and forms a support for the organ-loft, has escaped in a most wonderful manner, a few of the more projecting ornaments being merely detached. The organ, an instrument scarcely equalled in tone by any other in Europe, is totally destroyed. The oaken stalls,2 together with their richly carved canopies, have likewise perished. The altar table, which stood at the eastern end of the choir, on a raised pavement, ascended by a flight of fifteen steps, is likewise consumed, and the communion plate melted. The beautiful stone screen, which separated the Lady's Chapel from the altar, has not suffered so materially as was at first imagined. This elegant specimen of ancient sculpture is divided into eight pointed arches, and elaborately ornamented with tracery work: the lights were filled with plate glass, through which a fine view of the great eastern window was obtained; some pieces of which still remain uninjured.

Such are the principal parts of the cathedral which have suffered. The books, cushions, and other movable effects, from the northern side of the choir, were fortunately rescued, together with the brazen eagle, from which the prayers were read. The wills, and other valuable documents, were also preserved.

The choir, the destruction of which we have just related, was built by John de Thoresby, a prelate, raised to the archiepiscopal chair in 1532. On this building he expended the then enormous sum of one thousand eight hundred and ten pounds out of his own private purse. The first stone was laid on the 29th of July, 1361; but the founder died before its completion, as is evident from the arms of several of his successors in various parts of the building, particularly those of Scrope and Bowet, the latter of whom was not created archbishop until the year 1405. It was constructed in a more florid style of architecture than the rest of the fabric. The roof, higher by some feet than that of the nave, was more richly ornamented, an elegant kind of festoon work descending from the capitals of the pillars, which separated the middle from the side aisles; from these columns sprung the vaulted roof, the ribs of which crossed each other in angular compartments. The magnificent window, the admiration of all beholders, occupies nearly the whole space of the eastern end of the choir; it is divided by two large mullions into three principal divisions, which are again subdivided into three lights; the upper part from the springing of the arches are also separated into various compartments. It contains nearly two hundred subjects, principally scriptural. The painting of this window was executed about the year 1405, at the expense of the dean and chapter, by John Thornton, a glazier, of Coventry, who, by his contract, was engaged to finish it within three years, and to receive four shillings per week for his work; he was also to have one hundred shillings besides; and also ten pounds more if he did his work well.3 On the exterior of the choir, immediately over the window, is the effigy of John de Thoresby, mitred and robed, and sitting in his archiepiscopal chair, his right hand pointing to the window, and in his left holding the model of a church. At the base of the window are the heads of Christ and the Apostles, with that of some sovereign, supposed to be Edward III.

We will now bring this article to a close, by quoting the words of Æneas Sylvius, afterwards Pope Pius II., in praise of York Cathedral. He says, "It is famous all over the world for its magnificence and workmanship, but especially for a fine lightsome chapel, with shining walls, and small, thin-waisted pillars, quite round."4

S.I.BTHE VINE

FROM THE GERMAN OF HERDER(For the Mirror.)On the day of their creation, the trees boasted one to another, of their excellence. "Me, the Lord planted!" said the lofty cedar;—"strength, fragrance, and longevity, he bestowed on me."

"Jehovah fashioned me to be a blessing," said the shadowy palm; "utility and beauty he united in my form." The apple-tree, said, "Like a bridegroom among youths, I glow in my beauty amidst the trees of the grove!" The myrtle, said, "Like the rose among briars, so am I amidst the other shrubs." Thus all boasted;—the olive and the fig-tree—and even the fir.

The vine, alone, drooped silent to the ground! "To me," thought he, "every thing seems to have been refused;—I have neither stem—nor branches—nor flowers,—but such as I am, I will hope and wait." The vine bent down its shoots, and wept!

Not long had the vine to wait; for, behold, the divinity of earth, man, drew nigh; he saw the feeble, helpless, plant trailing its honours along the soil:—in pity, he lifted up the recumbent shoots, and twined the feeble plant around his own bower.

Now the winds played with its leaves and tendrils; and the warmth of the sun began to empurple its hard green grapes, and to prepare within them a sweet and delicious juice.

Decked with its rich clusters, the vine leaned towards its master, who tasted its refreshing fruit and juicy beverage; and he named the vine, his friend and favourite.

Despair not, ye forsaken; bear—be patient,—and strive.

From the insignificant reed flows the sweetest of juices;—from the bending vine springs the most delightful drink of the earth.

THE SKETCH-BOOK

THE BATTLE OF NAVARINO.—BY AN OFFICER ENGAGED.

(Abridged from No. 2, of the United Service Journal.)We had been cruizing off the coast of the Morea, for the protection of trading vessels, and to watch the motions of the numerous Greek pirates infesting the narrow seas and adjacent islands. For fourteen months we had been thus actively employed, when the arrival of the Albion and Genoa, from Lisbon, hinted to us, that some coercive measures were about to be used against the Turks, to cause them to discontinue the exterminating war they carried on against the Greeks, and to evacuate the country pursuant to the terms of the treaty of July, 1827. The prospect of a collision with the Turkish fleet appeared to be very agreeable to the ship's crew, as they had got a little tired of their long confinement on board, and anxiously looked for a speedy return to Malta to get ashore, which they had not been able to do for upwards of a year. We again proceeded on our protecting duty, and parted company with the admiral in the Asia. In about six weeks we returned, and found that many other British vessels had joined the Asia, whilst the squadrons of France and Russia added to the number of the fleet, which altogether presented an imposing attitude.

The Turkish and Egyptian fleets had arrived from the unsuccessful attempt in the Gulf of Patras some time before, and lay off the Bay of Navarino, before they finally entered and took up a position within the harbour. While the Ottoman fleet lay off the bay, the Turkish troops were said to have committed many unjustifiable outrages on the defenceless inhabitants of the country adjacent to Navarino; information of these oppressive acts was conveyed to the British admiral, and, it is believed, formed the grounds of a strong remonstrance on his part, addressed to the Turkish commanders, which hastened the collision between the two armaments. These facts were generally known throughout the fleet, and a "row" was eagerly expected.

About the beginning of October we had returned from our cruize; the men, ever since we had been in commission, had been daily exercised at the guns, and, by firing at marks, they had much improved in their practice.

Before entering the bay, the Ottoman fleet lay at the distance of ten or twelve miles from the Allies. They appeared numerous, with many small craft. Most of them bore the crimson flag flying at their peak, and on coming closer, a crescent and sword were visible on the flags. Their ships looked well, and in tolerable order: the Egyptians were evidently superior to the Turks.

Little communication took place between the Allied and Turkish fleets. The Dartmouth had gone into the bay twice, bearing the terms proposed by the allied commanders to Ibrahim Pacha. No satisfactory answer had been returned by the Ottoman admiral, whose conduct appeared evasive and trifling, implying a contempt for our prowess, and daring us to do our worst.

The Dartmouth having proceeded for the last time into the bay, with the final requisitions, and having brought back no satisfactory reply, on Saturday, the 20th of October, 1827, about noon, Admiral Codrington, favoured by a gentle sea-breeze, bore up under all sail for the mouth of the Bay of Navarino. A buzz ran instantly through the ship at the welcome intelligence of the admiral's bearing up; and I could easily perceive the hilarity and exultation of the seamen, and their impatience for the contest.

Our ship's crew was chiefly composed of young men, who had never seen a shot fired; yet, to judge from their manner, one would have thought them familiar with the business of fighting. The decks were then cleared for action, and the ship was quite ready, as we neared the mouth of the bay.

The Asia led the fleet, and was the first to enter the bay, followed by the ships in two columns. This was about one o'clock, or rather later. Abreast of Sir Edward Codrington was the French admiral, distinguished by the large white flag at the mizen. Then came the Genoa and Albion, followed by the Dartmouth, Talbot, and brigs, along with the French and Russian squadrons, in more distant succession. Every sail was set, so that the vast crowd of canvass, that looked more bleached and glittering in the rays of the sun, and contrasted with the deep blue unclouded sky, presented a magnificent and spirit-stirring spectacle. The breeze was just powerful enough to carry the allied fleet forward at a gentle rate, and as the wind freshened a little at times, it had the effect of causing the ships to heel to one side in a graceful, undulating manner,—the various flags and pendants of the united nations puffing out occasionally from the mast-heads. The sea was smooth, the weather rather warm, and the air quite clear. As we neared the entrance of the bay, the land presented all around a rugged, steep appearance towards the sea. In the distance, the mountains were visible, of a light blue, with whitish clouds apparently resting on their summits. The town and castle of Navarino presented a bright, picturesque look, and some spots of cultivation were to be seen. In the interior there rose in the air what looked like the smoke of some conflagration, and such we all believed was the case, as the Turkish soldiery had been employed in ravaging the country, and carrying away the inhabitants. An encampment of tents lay near, close to the castle, and large bodies of soldiers were easily discernible crowding on the batteries as we approached. We were about five hundred yards distant from the castle. The breadth of the entrance was about a mile.

When the Asia had arrived abreast of this castle, a boat rowed from the shore, and came alongside of the Asia with a request from Ibraham Pacha, that the allied fleets would not enter the bay; and just about that time, an unshotted gun was fired from the castle, which we interpreted as a signal for the Ottoman fleet to prepare for action. Close to the mouth of the bay, the cluster of vessels was considerable, all bearing up under a press of sail, and in perfect order. Our ship was close on the Asia's quarter. No opposition was made to our progress by the batteries of Navarino, which was a matter of surprise to all, as the men were ready at their quarters in momentary expectation of being attacked. To the spectators on the battlements our fleet must have presented a beautiful, though a formidable, appearance.

As soon as we had cleared the mouth of the bay, the Turko-Egyptian fleet was seen ranged round from right to left, in the form of an extensive crescent, in two lines, each ship with springs on her cables. Thus the combined fleets were in the centre of the lion's den, and the lists might be said to have been closed. The Asia, on passing the mouth of Navarino, sailed onwards to where the Turkish and Egyptian line-of-battle ships lay at anchor about three-quarters of a mile farther up the bay, and anchored close abreast one of their largest ships, bearing the flag of the Capitan Bey. The Genoa took her station near the Asia, whilst the Albion followed; but the Turks being so closely wedged together, she could not find space to pass between them to her appointed berth. The ship of the Egyptian Admiral lay as close to the Asia as that of the Capitan Bey: a large double-banked frigate was also near: all these three ships being moored in front of the crescent close upon the Asia and the Genoa. The wind by this time had almost died away, consequently the Albion had to anchor close alongside the double-banked frigate. This failing of the wind retarded considerably the progress of the ships, which had not yet entered the bay, particularly the Russian ships, and several of ours, which came later into action, and had to encounter the firing of the artillery of the castle.

The Egyptian fleet lay to the south-east; and, as it was well known that several French officers were serving on board, the French Admiral was appointed to place his squadron abreast of them. It appears, however, that, with one exception, all these Frenchmen quitted the Egyptian fleet, and went on board an Austrian transport which lay off the coast.

The post assigned to the Cambrian, Talbot, and Glasgow, along with the French frigate Armide, was alongside of the Turkish frigates at the left of the crescent on entering into the bay; whilst the Dartmouth, Musquito, the Rose, and Philomel, were ordered to keep a sharp look-out on the several fireships lurking suspiciously at the extremities of the crescent, and apparently ripe for mischief.

It was strictly enjoined in the orders, that no gun was to be fired, without a signal to that effect made by the Admiral, unless it should be in return for shots fired at us by the Turkish fleet. Each ship was to anchor with springs on her cables, if time allowed; and the orders concluded with the memorable words of Nelson,—"No captain can do very wrong who places his ship alongside of any enemy."

It was about two o'clock when we arrived at our station on the left of the bay, and anchored. The men were immediately sent aloft to furl the sails, which operation lasted a few minutes. Whilst so employed, the Dartmouth, distant about half a mile from our ship, had sent a boat, commanded by Lieut. Fitzroy, to request the fireship to remove from her station; a fire of musketry ensued from the fireship into the boat, killing the officer and several men. This brought on a return of small-arms from the Dartmouth and Syrene. Capt. Davis, of the Rose, having witnessed the firing of the Turkish vessel, went in one of his boats to assist that of the Dartmouth; and the crew of these two boats were in the act of climbing up the sides of the fireship, when she instantly exploded with a tremendous concussion, blowing the men into the water, and killing and disabling several in the boats close alongside. Just about this time, and before the men had descended from the yards, an Egyptian double-banked frigate poured a broadside into our ship. The captain gave instant orders to fire away; and the broadside was returned with terrible effect, every shot striking the hull of the Egyptian frigate. The men were now hastily descending the shrouds, while the captain sung out, "Now, my lads! down to the main-deck, and fire away as fast as you can." The seamen cheered loudly as they fired the first broadside, and continued to do so at intervals during the action. The battle had actually commenced to windward before the Asia and the Ottoman admiral had exchanged a single shot; and the action in that part of the bay was brought on in nearly a similar manner as in ours, by the Turks firing into the boat dispatched by Sir E. Codrington to explain the mediatorial views of the Allies. The Greek pilot had been killed; and ere the Asia's boat had reached the ship, the firing was unremitting between the Asia, Genoa, and Albion, and the Turkish ships. About half-past two o'clock, the battle had become general throughout the whole lines, and the cannonade was one uninterrupted crash, louder than any thunder. Previous to the Egyptian frigate firing into us, the men, not engaged in furling the sails, had stripped themselves to their duck-frocks, and were binding their black-silk neckcloths round their heads and waists, and some upon their left knees.

The Egyptian frigate, which had fired into our ship was distant about half a cable's length. Near her was another of the same large class, together with a Turkish frigate and a corvette. These four ships poured their broadsides into us without intermission for nearly a quarter of an hour; but after a few rounds their firing became irregular and hasty, and many of their shots injured our rigging. At the first broadside we received, two men near me were instantly struck dead on the deck. There was no appearance of any wounds upon them, but they never stirred a limb; and their bodies, after lying a little beside the gun at which they had been working, were dragged amid-ships. Several of the men were now severely wounded.