Полная версия

Полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 5, 1920

Laws of Mo., 1915, p. 69.

291

Report of Commissioner of Education, 1916, p. 586.

292

Negro Year Book, 1917, pp. 234-241.

293

Ibid., pp. 234-240.

294

Ibid.

295

Missouri had 174 illiterate out of every one thousand, and Oklahoma and West Virginia had 177 and 203 respectively.

296

This dissertation was in 1917 submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Literature of the University of Chicago, in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts, by David Henry Sims.

The following sources were used in the preparation of this dissertation: American Missionary Association Report, 1916; Baptist Missionary Society (Woman's) Reports, 1910-1916; Catalogues—Negro Colleges, 1916-1917; W. E.B. DuBois, Morals and Manners Among Negro Americans, Atlanta University Publications, No. 18; Journal of the Proceedings of the A. M. E. Church (General Conference), 1916; Journal of the Proceedings of the Methodist Episcopal Church (General Conference), 1916; Thomas J. Jones, Negro Education, United States Bureau of Education, Bulletins 38 and 39, 1916; Thomas J. Jones, Recent Movements in Negro Education, United States Bureau of Education, 1912, Vol. I; Questionnaires, from Negro Colleges, 1917; United States Bureau of Education Investigations, Education in the South, Bulletin 30, 1933; Monroe N. Work, Negro Year Book, 1914, 1915, 1916; Young Men's Christian Association, Report of the International Committee, May 12, 1916; Year Book, 1915-1916.

The author used also the following works for general reference: W. S. Athearn, Religion in the Curriculum-Religious Education; R. E. Bolton, Principles of Education; H. F. Cope, The Efficient Layman; H. F. Cope, Fifteen Years of the Religious Education Association, The American Journal of Theology, July 1917, p. 385 ff; Committee Report, Standardization of Biblical Courses, Rel. Educ. August, 1916, p. 314 ff; Crawford, The Media of Religious Impression in College, N. E. A. 1914, p. 494 ff; John Dewey, Ethical Principles Underlying Education, Moral Principles in Education; T. S. O. Evans, The University Young Men's Christian Association as a Training School for Religious Leaders, Rel. Educ. 1908; H. F. Fowler, The Contents of an Ideal Curriculum of Religious Education for Colleges, Rel. Educ. 1915, p. 355 ff; E. N. Hardy, The Churches and The Educated Man; S. B. Haslett, Pedagogical Bible School, Parts I and II; International Sunday School Association, Organized Work in America, Vol. XIII; C. F. Kent, Training the College Teacher, Rel. Educ. 1915, Vol. X, p. 327; P. Monroe, Cyclopedia of Education, Vol. I, p. 370; E. C. Moore, What is Education; A. Morgan, Education and Social Progress; F. G. Peabody, The Religious Education of an American Child, Rel. Educ. 1915, p. 107; I. J. Peritz, The Contents of an Ideal Curriculum of Religious Instruction, Rel. Educ. Vol. X, 1915, p. 362; C. Reed, The Essential Place of Religion in Education, N. E. A. Monograph Publication, 1913, p. 66; R. Rhees, Evangelisation of Education, Biblical World, August 1916, p. 66; C. E. Pugh, The Essential Place of Religion in Education, N. E. A. Monograph Publication, 1913, p. 3; I. T. Wood, The Contents of an Ideal Curriculum of Religious Instruction for Colleges, Rel. Educ. 1915, Vol. X, p. 332; The Survey of Progress in Religious and Moral Education, Rel. Educ. 1915, Vol. X, p. 114.

297

None of these does all of the things described, but all of them do at least some one of them.

298

Dewey, Ethical Principles Underlying Education.

299

Ideals in Religious Education, R.E.A., June, 1917, p. 185.

300

Ibid., p. 94.

301

Dewey, Ethical Principles Underlying Education.

302

Pedagogical Bible School, page 207.

303

R. E. A., April 19, 1917, page 123.

304

Nat Turner was a familiar name in the household in which the author was reared, as his home was within fifty miles of the place of Turner's exploits. In 1871, the last term of the author's service as a teacher in the public schools of Virginia, was spent in this same county, with a people, many of whom personally knew Nat Turner and his comrades.

Nat Turner was born October 2, 1800, the slave of Benjamin Turner. His father, a native of Africa, escaped from slavery and finally emigrated to Liberia, where, it is said, his grave is quite as well known as that of Franklin's, Jefferson's or Adams's is to the patriotic American. There is now living in the city of Baltimore a man who on good authority claims to be the grandson of Nat Turner and a son of his was said to be still living in Southampton County, Virginia, in 1896.

In his early years Turner had a presentiment which largely influenced his subsequent life and confirmed him in the belief that he was destined to play an unusual rôle in history. That prenatal influence gave him a marked individuality is readily believed when the date of his birth is recalled, the period when the excitement over the discovery of Gabriel Prosser's plot was at its height. Nat's mind was very restless and active, inquisitive and observant. He learned to read and write with no apparent difficulty. This ability gave him opportunity to confirm impressions as to knowledge of subjects in which he had received no instruction. When not working for his master, he was engaged in prayer or in making sundry experiments. By intuition he, in a rude way, manufactured paper, gunpowder, pottery and other articles in common use. This knowledge which he claimed to possess was tested by actual demonstration during the trial for his life. His superior skill in planning was universally admitted by his fellow workmen. He did not, however, attribute this superior influence to sorcery, conjuration or such like agencies, for he had the utmost contempt for these delusions.

"To this day," says T. W. Higginson, "There are the Virginia slave traditions of the keen devices of Prophet Nat. If he were caught with lime and lampblack in hand conning over a half-finished county map on the barn door, he was always planning what he would do if he were blind. When he had called a meeting of slaves and some poor whites came eavesdropping, the poor whites at once became the topic of discussion; he incidentally mentioned that the master had been heard threatening to drive them away; one slave had been ordered to shoot Mr. Jones' pigs, another to tear down Mr. Johnson's fences. The poor whites, Johnson and Jones, ran home at once to see to their homesteads and were better friends than ever to poor Nat."—T. W. Higginson's Travellers and Outlaws, pp. 282-283.

305

T. W. Higginson's Travellers and Outlaws, p. 284.

306

Nat Turner's Confessions.

307

Drewry, The Southampton Insurrection, pp. 35-74.

308

The Richmond Enquirer, Aug. 30, Sept. 4, 6 and 20, 1831.

309

Based on statements made to the author by contemporaries of Nat Turner.

310

Higginson, Travellers and Outlaws, p. 300.

311

The statement of Rev. M.B. Cox, a Liberian Missionary, then in Virginia.

312

Higginson, Travellers and Outlaws, 302-303.

313

Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, p. 9.

314

Drewry, The Southampton Insurrection, 102.

315

The Richmond Enquirer, August 30 and September and October, 1831.

316

The Richmond Enquirer, Sept. 4, 1831.

317

Higginson, Travellers and Outlaws, 303.

318

The Richmond Enquirer, Nov. 4 and 8, 1831.

319

The Richmond Enquirer, Nov. 4, 1831.

320

The trial and execution over, the Confessions of Nat were published in pamphlet form and had a wide sale. An accurate likeness by John Crawley, a former artist of Norfolk at that time, lithographed by Endicott and Sweet of Baltimore, accompanied the edition which was printed for T. R. Gray, Turner's attorney. Fully 50,000 copies of this pamphlet are said to have been sold within a few weeks of its publication, yet today they are exceedingly rare, not a copy being found either in the State Library at Richmond, the Public Library at Boston nor the Congressional Library at Washington. These Confessions purport to give from Turner's own lips circumstances of his life. "Portions of it," says The Richmond Enquirer, "are eloquent and even classically expressed; but," continues the critic, more than sixty miles away, "the language is far superior to what Nat Turner could have employed, thereby giving him a character for intelligence which he does not deserve and should not receive." On the contrary, however, Mr. Gray, his attorney and confessor who did not write from long range, said: "As to his ignorance, he certainly had not the advantages of education, but he can read and write and for natural intelligence and quickness of apprehension is surpassed by few men I have ever seen. Further the calm, deliberate composure with which he spoke of his late deeds and intentions, the expression of his fiend-like face when excited by enthusiasm; still bearing the stains of the blood of helpless innocence about him; clothed with rags and covered with chains, yet daring to raise his manacled hands to heaven; with a spirit soaring above the attributes of man, I looked on him and my blood curdled in my veins."—The Confessions of Nat Turner.

321

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, pp. 9 and 10.

322

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, p. 10.

323

In Fluvanna this memorial of certain ladies was agreed upon and sent to the legislature: "We cannot conceal from ourselves that an evil is among us, which threatens to outgrow the growth and eclipse the brightness of our national blessings. Our daughters and their daughters are destined to become, in their turn, the tender fosterers of helpless infancy, the directors of developing childhood, and the companions of those citizens, who will occupy the legislative and executive offices of their country. Can we calmly anticipate the condition of the Southern States at that period, should no remedy be devised to arrest the progressive miseries attendant on slavery? Will the absent father's heart be at peace, when, amid the hurry of public affairs, his truant thoughts return to the home of his affection, surrounded by doubtful, if not dangerous, subjects to precarious authority? Perhaps when deeply engaged in his legislative duties his heart may quail and his tongue falter with irresistible apprehension for the peace and safety of objects dearer than life.

"We can only aid the mighty task by ardent outpourings of the spirit of supplication at the Throne of Grace. We will call upon the God, in whom we trust, to direct your counsels by His unerring wisdom, guide you with His effectual spirit. We now conjure you by the sacred charities of kindred, by the solemn obligations of justice, by every consideration of domestic affection and patriotic duty, to nerve every faculty of your minds to the investigation of this important subject, and let not the united voices of your mothers, wives, daughters and kindred have sounded in vain in your ears."—Drewry, The Southampton Insurrection, p. 165.

324

Drewry, The Southampton Insurrection, pp. 1-100.

325

October 18. This memorial circulated in Petersburg and in adjoining towns and counties is typical:

"The undersigned good citizens of the County of ........ invite the attention of your honorable body to a subject deemed by them of primary importance to their present welfare and future security.

"The mistaken humanity of the people of Virginia, and of our predecessors, has permitted to remain in this Commonwealth a class of people who are neither freemen nor slaves. The mark set on them by nature precludes their enjoyment in this country, of the privileges of the former; and the laws of the land do not allow them to be reduced to the condition of the latter. Hence they are of necessity degraded, profligate, vicious, turbulent and discontented.

"More frequent than whites (probably in tenfold proportion) sustained by the charitable provisions of our laws, they are altogether a burden on the community. Pursuing no course of regular business, and negligent of everything like economy and husbandry, they are as a part of the community, supported by the productive industry of others.

"But their residence among us is yet more objectionable on other accounts. It is incompatible with the tranquility of society; their apparent exemption from want and care and servitude to business, excites impracticable hopes in the minds of those who are even more ignorant and unreflecting—and their locomotive habits fit them for a dangerous agency in schemes, wild and visionary, but disgusting and annoying.

"We would not be cruel and unchristian—but we must take care of the interests and morals of society, and of the peace of mind of the helpless in our families. It is indispensable to the happiness of the latter, that this cause of apprehension be removed. And efforts to this end are, we firmly believe, sanctioned by enlightened humanity toward the ill-fated class to whom we allude. They can never have the respect and intercourse here which are essential to rational happiness, and social enjoyment and improvement. But in other lands they may become an orderly, sober, industrious, moral, enlightened and christian community; and be the happy instruments of planting and diffusing those blessings over a barbarous and benighted continent.

"Your petitioners will not designate a plan of legislative operation—they leave to the wisdom and provident forecast of the General Assembly, the conception and the prosecution of the best practicable scheme—but they would respectfully and earnestly ask that the action of the laws passed to this effect be decisive, and the means energetic—such as shall, with as much speed as may be, free our country from this bane of its prosperity, morality and peace."—The Richmond Enquirer, Oct. 21, 1831.

326

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, pp. 1-123.

327

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, pp. 41, 56, 119.

328

Ibid., 1831, p. 93.

329

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, p. 93.

330

Ibid., p. 93.

331

Ibid., p. 125.

332

The Richmond Enquirer, Jan. 7, 1832.

333

Drewry, The Southampton Insurrection, p. 165.

334

The Richmond Enquirer, Dec. 17, 1831.

335

Ibid., Nov. 18, 1831.

336

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, p. 110.

337

Before the insurrection free men of color voted in North Carolina and at least one well-authenticated case exists of a colored voter in Virginia prior to 1830. A native of Virginia long a resident of Massachusetts is an authority for the statement that the facilities for higher education of the Negro were quite as good in Richmond as in Boston at that time. There was published in a paper of the time an account of the celebration of the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1827, by the free people of color of the city of Fredericksburg, Virginia. The orator of the day was Isaac N. Carey.

In North Carolina John Chavis, a Negro, rose to such excellence as a teacher of white youth that he is pronounced in a biographical sketch, contained in a history of education in that State, published by the United States Bureau of Education, as one of the most eminent men produced by that State. Though an unmistakable Negro, as a preacher he acceptably filled many a white pulpit and was welcomed as a social guest at many a fireside. Such was the bitterness against the race growing out of Nat Turner's Insurrection, however, that even such a man fell under the ban of proscription.

One of the preachers to whom Governor Floyd had reference quietly ignored the suggestion in the message of his Excellency and kept up his work. He was a Baptist preacher, William Carney, the grandfather of the famous Sergeant William H. Carney, of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. At the same time a daughter of his and a Methodist in a neighboring town "bearded the lion in his den" by actually collaring and driving out the leader of a party of white men who broke into a Negro religious meeting.

338

The Richmond Enquirer, Jan. 11, 1839.

339

Ibid., Jan. 11, 1839.

340

Ibid., Jan. 19, 1832.

341

Ibid., Jan. 24, 1832.

342

The Richmond Enquirer, Jan. 25, 1832.

343

Ibid., Jan. 26, 1832.

344

The Richmond Enquirer, Jan. 27, 1832.

345

Ibid., Nov. 18, 1831.

346

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, p. 10.

347

Ibid., p. 112.

348

Ibid., 1831, p. 125.

349

Ibid., 1831, p. 131.

350

The Richmond Enquirer, Jan. and Feb., 1832.

351

The Journal of the House of Delegates, 1831, Appendix, Bill No. 7.

352

Ibid., Bill No. 13.

353

Hurd, Law of Freedom and Bondage, II, 9.

354

The Laws of Maryland, 1831-32, c. 281.

355

Ibid., c. 328.

356

See Article IV, Sec. 1.

357

Revised Code of Maryland, Chap. 52 and 237.7

358

The Laws of Tenn., 1831, Chaps. 102 and 103.

359

Cobb's Digest of the Laws of Georgia, 1005.

360

Revised Statutes of North Carolina, c. 109 and 111.

361

Hurd, Law of Freedom and Bondage, II, 146.

362

Ibid., II, 162.

363

Laws of Louisiana, 1830, p. 90, Sec. 1.

364

Annual Laws of Alabama, 1832, p. 12.

365

Columbia State, December 24, 1918.

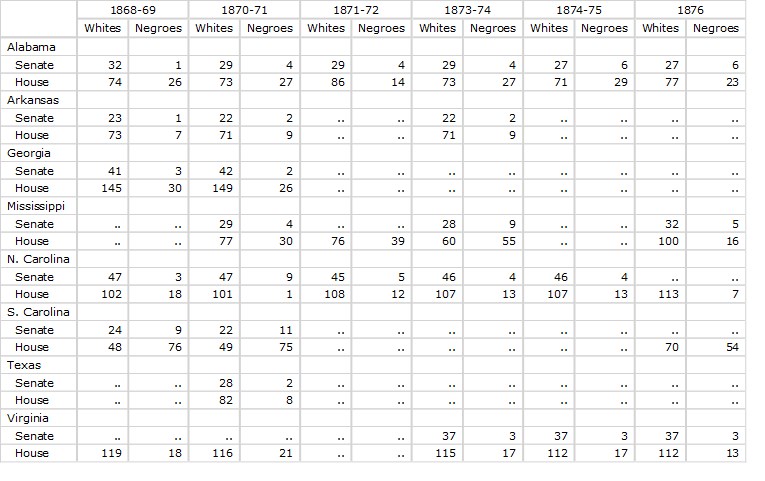

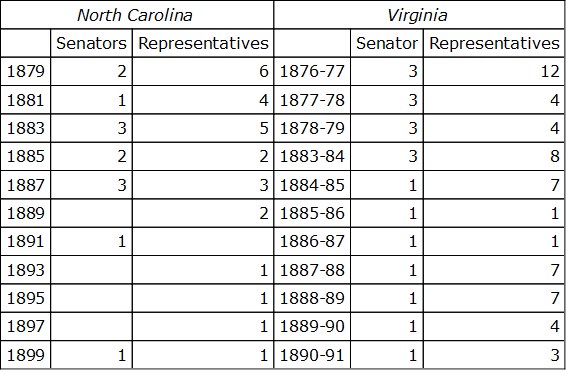

A Summary of Negro Members of Some Reconstruction Legislatures

There were Negro members of the North Carolina legislature to 1899 and of the Virginia legislature to 1891 as follows:

366

Annual Cyclopedia, 1868, pp. 34-35.

Mr. Monroe N. Work, who compiled the records of the Negro in politics during the Reconstruction period, has received the following interesting letters containing some valuable facts:

1425 McCulloh St., Baltimore, Md., Feb. 9, 1920.My dear Mr. Work:

Referring to the "Journal of Negro History" for Jan., 1920, in the letter of the State Librarian of Virginia, page 119, occur these words: "For the 1881-2 session the almanac has no list of members."

It so happens that the writer was present, and was an employee of that particular session of the Virginia Legislature, and therefore takes pleasure in supplying the necessary information.

The speaker of the House of Representatives was the Hon. I.C. Fowler, and the President protem (the Lieutenant Governor, John F. Lewis, being President) of the Senate was the Hon. H.C. Wood. The Governor of the State at that time was the Hon. William E. Cameron, from my home town, Petersburg. It was quite a memorable session, and I could almost write a book, with respect to matters as they pertained to the Negro. The Hon. William Mahone was United States Senator, and although a boy, I was much trusted by Senator Mahone; and in many important conferences held in the old "Whig" building, I was quite active in helping to prevent none but "the faithful" from entering.

Upon the assembling of the Legislature, I was appointed one of the six pages in the House. The other five were white boys. Very soon afterwards, I was promoted to the postmastership of the House. On the Senate side, there were two colored boys as pages, a son of ex-Senator Moseley of Goochland Co., and a son of the late R.G.L. Paige, representative from Norfolk county.

There were three colored men in the Senate Chamber, and two of them were really able and scholarly men, and were among the leading debaters in that chamber. One was Dr. Dan Norton, from the Yorktown District, another was Senator William N. Stevens, representing the senatorial district of Sussex and Greensville counties. Senator Stevens was a speaker of much elegance and grace, and was always listened to with respect and admiration. Then there was Senator J. Richard Jones, representing Charlotte and Mecklenburg counties.

In the Lower House, there were thirteen colored representatives; the names of two I can not just recall, but the others I will mention.

Norfolk county, R.G.L. Paige.

Princess Anne county, Littleton Owens.

York county, Robert Norton.

City of Petersburg, Armstead Green.

Dinwiddie county, Alfred W. Harris.

Powhatan county, Neverson Lewis.

Brunswick county, Guy Powell.

Cumberland county, Shed Dungee.

Prince Edward county, Batt Greggs.

Amelia and Nottoway, Archie Scott.

Mecklenburg county, Ross Hamilton.

Paige and Harris were thoroughly educated men, while Ross Hamilton possessing only limited literary qualifications, was a most remarkable man, and one of the parliamentary authorities of that body. In the preceding session, of which Hamilton was a member, he got to himself great fame by the introduction of the measure known and referred to as the "Ross Hamilton bill." It had to do with the settlement of the Virginia debt, the great issue on which Mahone rode into power.

Paige and Harris were among the principal leaders of the House, and certainly, few were the men in that house whether democrats or republicans, who could outrank them in oratory or public debate.

Mr. Harris introduced the measure which provided for the present state Normal school, at Petersburg, carrying with it an appropriation of one hundred thousand dollars. I had the great pleasure of bearing the bill to the Speaker's desk.