Полная версия

Полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 5, 1920

No account of the final settlement of these claims, however, is found in the sources. Dissatisfaction became more intense. Claimants were pressing on all sides for a fair compensation for the loss of their property. So serious was the situation that the House of Representatives went beyond its accustomed limitation and discussed in 1798 the treaty-making power of the United States. Pressure had been brought to bear upon the representatives of the people because the Jay Treaty had been ratified by the President and Senate and it did not contain a provision covering the return of the Negroes.

Further efforts, nevertheless, were made to adjust the differences between the two countries. They, however, were of little avail. The Republican policy of Jefferson which this country strictly followed from 1801 to 1809 had as its basic principle that governments ought to do as little as possible. Hence our army and navy were cut down to the extent that the American Government could not assert itself against foreign encroachment. Particularly in 1804 our relations with Great Britain became worse when the Jay Treaty of 1794 by agreement was allowed to expire. To compel Great Britain to come to terms Congress enacted a non-important act which never had the desired effect.

Soon thereafter the continental system and the paper blockade engaged the attention of the American Government. Negotiations had failed. Great Britain would not make a treaty. The accumulation of injuries called for action of some kind. To yield and say nothing meant to give up the rights of an independent nation. For this reason Jefferson introduced in 1807 the Embargo with which he hoped to force France as well as Great Britain to come to terms—to recognize the United States as a "free sovereign and independent nation." Meanwhile a spirit of nationality was developing in the country. Soon thereafter war was declared and waged against Great Britain to win the respect and honor which every nation deserves.

In this state of war the provisions of the Treaty of Paris and the Jay Treaty were nullified. In response to an inquiry as to whether these treaties, so far as they were not fully executed, terminated by the War of 1812, the British Department of State in a communication replied that "with respect to the treaties you are informed that they were claimed by Great Britain at the conclusion of the Treaty of Ghent to have terminated by the War of 1812."

Against this view the United States protested. In the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel v. the Town of New Haven, the view was expressed that provisions of a treaty remain in full force in spite of war.623 The general rule of inter-national law, however, is that war terminates all subsisting treaties between the belligerent powers.624 The United States, moreover, soon acquiesced in this view, for President Polk in his message to Congress, December 7, 1847, said, "a state of war abrogates treaties previously existing between the belligerents."625 Great Britain then was legally excused by the best authorities of the world from executing fully the provisions of the Treaty of 1783 and the Jay Treaty of 1794.

As a result, the same policy in regard to the carrying away of Negroes was followed during the War of 1812.626 While the British forces were occupying the forts and harbors of the United States, Negroes came within their possession. Many were induced to run away while others were captured in battles. From the Dauphin Islands-possessions claimed to be without the limits of the newly acquired Louisiana territory the British carried away slaves. In fact, from whatever places the British occupied they carried away Negroes. Many Negroes came also into the possession of the British by the proclamation of Admiral Cochrane of Great Britain, April 2, 1814, setting such loyal adherents free. In effect, this proclamation extended an invitation to all persons desiring to change their slave status. Although the proclamation627 did not specify the Negroes, the meaning and object of Admiral Cochrane was evidently to bring Negroes within the British lines. Many, to be sure, responded to the proclamation. As many more, no doubt, were carried away from the United States by the British under the veil that they were captives in the war and, therefore, no longer the property of American inhabitants.

With victory assured and the representatives of Great Britain and America assembled in Ghent, July 11, 1814, one of the first questions for the commissioners to consider was evidently the return of the Negroes. This question had primary consideration in the final draft of the Treaty of Ghent. By the first article of the treaty it was provided that "all possessions whatsoever taken by either party during the war or which might have been taken after the signing of this treaty shall be restored without delay and that these possessions should not be destroyed." It specified, moreover, that artillery, public and private property, originally captured in the forts of the United States should not be carried away.628

Negroes were carried away by the British forces after the treaty was signed as well as before. In Georgia many Negroes came into possession of the British at Cumberland Island fortified by Admiral Cockburn.629 In a letter dated November 22, 1914, Joseph Cabell gave evidence to support the above-mentioned facts when he declared that he was on board a British squadron in Lynnhaven Bay at the time Major Thomas of York attempted to recover his Negroes, who had gone off to the British and that the destination of the Negroes on board the ships was a subject of curiosity and concern. Soon, however, he learned that they were to be sold in the Bahamas.630 From another reliable source comes the information that a shameful traffic had been carried on in the West Indies.631 Secretary Monroe presented to the Senate, moreover, an affidavit of a Captain Williams who had been a prisoner in the Bahamas for some time. In this he declared that he had been present at the sale of Negroes taken from the vicinity of Norfolk and Hampton. "This affidavit," said Monroe, "was voluntarily given and the facts have been corroborated by a variety of circumstances."

Such information was given in the Senate. In discussing the ratification of the treaty the Senate suggested that commissioners be appointed to carry into effect the first article. In line with this view John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and Albert Gallatin were authorized to supervise the execution of this article. In a communication to Secretary Monroe, Feb. 23, 1815, the commissioners reported that "all slaves and other private property are claimed to be delivered up."632

So much progress in so short a time was remarkable. To adjust all the claims in an amicable way would hardly occur. It was soon learned by the commissioners that "all slaves and other private property" were delivered up by the British using as their guide a different construction of Article I. "The construction," Monroe said, "ignored the distinction which existed between public and private property." Had it been intended he continued, "to put slaves and other private property on the same ground with artillery and other public property the terms "originally captured in the said forts or places which shall remain therein on the exchange of the ratification of the Treaty" would have followed at the end of the sentence after "slaves and other private property."633 With their construction, he contended that both interests, the public and private would have been subject to the same limitation. Besides, Monroe held that the restrictive words immediately following "artillery and other public property" was not intended to include the words "slaves and other private property." If "the slaves and other private property" are placed on the same footing with artillery and other public property, "the consequences must be that all will be carried away."

Monroe learned, furthermore, that Mr. Baker, Charge D'affaires of Great Britain, had placed another construction on Article I of the treaty. In this new construction he had made a distinction between slaves who were in British ships of war in American waters and those in the ports held by British forces at the time of the exchange of ratifications.634 Monroe and the commissioners, on the other hand, were of the opinion that the United States was entitled to all slaves in possession of the British forces within the limits of the United States forts or British ships of war. Concerning this opinion Baker wrote April 3, 1815, that it could not be shown that Monroe's construction was sanctioned by the words of the Article. "If this construction had been known then," he remarked, "we would have decidedly objected to it and proposed others."635

Accessible reports indicate that the governments of Great Britain and the United States persisted in the constructions given by their respective representatives. Clavelle, the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in the Chesapeake, claimed that the treaty meant only such slaves or other private property should be delivered up as were "originally captured in the forts or places to be restored." In conformity with their construction of the Article, Clavelle refused furthermore to restore the slaves taken from Tangier Islands, because they were not originally captured there. The United States, on the other hand, was of the opinion that the country was entitled to all slaves within its limits on the exchange of the ratifications of the treaty. The United States believed, finally, that the carrying away of Negroes applied to both kinds of property because the word was common to both descriptions.

By the usage of civilized nations in cases of invasion private property with the exception of maritime captures was respected. This meant, in effect, that none could be lawfully taken away. Influenced by this usage Great Britain receded from her position and declared that the claim of the United States to indemnification for her slaves—had never been resisted. In the meantime Great Britain declared April 10, 1816, that she could not consider any property which had been previous to ratification of the treaty removed on shipboard as "property forming a subject for a claim of restoration or indemnification." In spirit, these two declarations were contradictory. Besides they made the subject more difficult and puzzling.

In the meanwhile the work of the commissioners continued. In their efforts to take an inventory of the slaves so that the claims might be adjusted, they encountered the opposition of Clavelle and Cockburn. It was clearly evident that the efforts of the commissioners would be of no avail. More coercive means were necessary to settle such an extended and controversial question. In a convention of commerce between Great Britain and the United States October 20, 1818, representatives realized that an agreement in regard to the Negroes was hardly possible. The representatives from the United States, therefore, offered to refer the differences to some friendly sovereign or State to be named for that purpose. They agreed further to consider the decision of such a friendly sovereign or State to be "final and conclusive."636

Very soon thereafter the Emperor of Russia offered to use his good offices as mediator and after a short discussion, his proposal was accepted. To this end there was concluded on June 30, 1822, a convention in which the adjustment of the claims for indemnity was left to a mixed commission. This action was followed by desultory and extended discussions which terminated, nevertheless, in the final disposition of the controversy. The point of difference was decided in favor of the United States. In handing down his decision the Emperor held that the limitations as to the restitution of public property bore no relation to private property. In effect, he said that the treaty prohibited the carrying away of any private property whatever from the places and territories stipulated in Article I of the Treaty of Ghent. He contended that "the United States was entitled to consider as having been carried away all slaves who had been transported from those territories on board of English vessels within the waters of American territories and who for that reason had not been restored."637

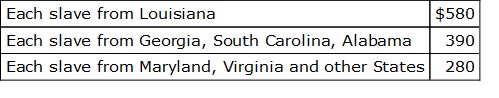

In compliance with the decision of the Emperor of Russia a mixed commission, one commissioner and one arbitrator from Great Britain as well as the United States met July 30, 1822, at Washington, D.C., under the Emperor's mediation.638 For the United States Langdon Cheves was the commissioner and Henry Sewell the arbitrator; for Great Britain George Jackson was the commissioner and John McTavish the arbitrator. George Hay was appointed, also, by the President of the United States to give such information and support that might be needed since individual claimants could not be present. The purpose of the commission was to prove the average value of the Negroes at the time of the ratification of the treaty and to determine the validity of individual claims. In the event no agreement could be reached recourse was had to the Emperor of Russia whose decision would be "final and conclusive." This action was insisted upon by America, whereas Great Britain persisted in refusing to submit such matters to the Emperor. Their progress, as a result, was not very marked. In considering the "definitive lists"639 of claims these commissioners encountered many more doubtful and intricate problems. Claims not contained in this list were not to be taken cognizance of; nor was the British government required to make compensation for them. With respect to compensation, Great Britain promised to produce all evidence which was in the possession of her naval and military officers concerning the number of slaves carried away. It was provided by the commission that no payment was to be made within twelve months. September 11, 1822, the board unanimously agreed on the average value of slaves as follows:

The next difficulty of the board occurred in regard to the allowance of interest on claims. Concerning this point, Cheves held that a reasonable compensation for the injury sustained should have been granted. "A just compensation," said Cheves, "is the reestablishment of the thing taken away with an equivalent for the use of it during the period of detention." In reply to this Jackson held that the convention of 1822 did not grant the commissioners the power to fix interests and, besides, that interests not being a part of the debt could not be allowed. Realizing the futility of his claims Cheves offered to submit the difference to arbitration, but Jackson declined.

Equally difficult questions arose in regard to the slaves taken away from Dauphin Island in Mobile Bay.640 This island, controlled by the British during the war, was later surrendered to the United States. Concerning this Jackson held that it was not legally at the time of the ratifications of the treaty a part of the United States, that is, it was not a part of Louisiana but belonged to West Florida, which was not ceded to the United States until 1819.641 In regard to this Cheves offered to refer these claims to arbitration, but in this view Jackson refused to acquiesce. The situation did not become any better even when Rufus King was sent as our minister to England to succeed Henry Clay who became John Quincy Adams's Secretary of State.

Continued disagreement of the representatives of Great Britain and the United States resulted. Their failure to agree upon the provisions of the Convention of 1822—that matters under dispute be referred to arbitration made the work of this convention of little avail. Clay's offer of settlement was not favorably received in Great Britain. As to a basis of compromise, Clay said that the "total number of slaves on the definitive list was 3,601; that the entire value of all the property for which the indemnity was claimed including interest might be stated at $2,693,120." Realizing that this large sum would never be secured, Clay suggested that $1,151,800 might be used as the minimum in the negotiation. He used as a guide the fact that Parliament had appropriated 250,000 pounds to cover the awards of the commission. This sum, Mr. King observed also, was nearly the sum mentioned as a minimum by Clay in his instructions to him. Even with this information, the commissioners made little progress.

On the other hand, Mr. Vaughan, the British Envoy at Washington, said April 12, 1826, "that His Majesty's Government regretted to find themselves under the absolute impossibility of accepting the terms of compromise offered by the envoy from the United States in London." He did not admit, moreover, that the question of interest should be referred to arbitration, but maintained that the demand was unwarranted by the convention and unfounded by the Law Officers of the Crown.642 In reply to his observation, Clay informed Vaughan of the fact that Great Britain's representatives had refused to refer many questions to arbitration and that if this refusal to cooperate in this regard should be upheld it would virtually be making him the final judge of every question of difference that arose in the joint commission.643 This disagreement continued until 1825, when the commissioners met to collect and weigh evidence.

Soon thereafter, Albert Gallatin, who had been appointed Envoy of the United States to London, was authorized to treat with Canning on the oft-discussed question. During the first interview he discovered that, while there was a great reluctance to recede from the ground already taken by Jackson, there was also a disposition to settle that controversy.644 Following the instructions given to King, Gallatin used the 250,000 pounds as the basis of settlement. This sum he was authorized to accept. He, however, did not make this offer known immediately but waited for the formal offer of $1,200,000 from the British Government; and in conformity with his instruction of a later date, Gallatin offered as an ultimatum an acceptance of $1,204,960, which the British Government reluctantly agreed to pay.645

On November 13, 1826, a convention to carry out this agreement was concluded. The amount specified above was to cover all claims under the award of the Emperor of Russia. It provided, moreover, that the money was to be paid in Washington, in the current money of the United States, in two installments; the first twenty days after the British Minister in the United States should have been officially notified of the ratifications of the convention, and the second August 1, 1827. In this way the convention of 1822 was annulled, save as to the two articles relating to the average value of slaves which had been carried into effect, and as to the third article as related to the definitive list which had also been carried out.646 This ended the work of the board. After ratification had been exchanged the board adjourned, March 26, 1827.

This left one more matter to be disposed of, that of executing the provisions of the commission of 1826. In compliance with this Congress passed an act, March 2, 1827, to carry out this agreement.647 A convention was thereby called to meet in Washington July 10th and proceed with the consideration of claims, "allowing such further time for the production of evidence as they should think just." As soon as the claims were validated and the principal amounts ascertained seventy-five per cent of the principal was paid with the explanation that when all claims were settled, the other twenty-five per cent would be paid, if the fund permitted it. If it did not, then the remainder would be distributed in proportion to the sums awarded. In these negotiations, Langdon Cheves and Henry Sewell, who had only recently represented the United States in London, together with James Pleasants of Virginia, were appointed commissioners. They considered not only the claims on the definitive list but also those deposited in the Department of State and which had not been previously adjusted.

The conflicting interests of payments and the inconclusive evidence which were presented made the work of this convention more difficult. The records were very poor and contained little of the information desired. For this reason many claims were denied; especially was this true in Maryland and Virginia.648 Many of the claimants of other States nevertheless were compensated. Seventy-five per cent was granted them, the sum totalling $600,000 being paid. This condition of affairs caused a clash among the 1,100 claimants, 700 of whose petitions on the definitive list were examined. Many other claimants were seeking evidence to secure compensation. They were not successful, however, for Cheves opposed the admission of hearsay testimony as well as the testimony of slaves. Well informed as to the progress of the commission, Congress passed an act May 15, 1828,649 specifying August 31st as the last day on which the commission would meet. Of that entire amount awarded $1,197,422.18 had been paid to the claimants. The remaining sum was "distributed and paid ratably," to all the claimants to whom compensation had been made. The work of the Convention of 1827 thus ended.

Arnett G. LindsayTHE NEGRO IN POLITICS 650

A treatise on the Negro in politics since the emancipation of the race may be divided into three periods; that of the Reconstruction, when the Negroes in connection with the interlopers and sympathetic whites controlled the Southern States, the one of repression following the restoration of the radical whites to power, and the new day when the Negro counts as a figure in politics as a result of his worth in the community and his ability to render the parties and the government valuable service.

While the echoes of the Civil War were dying away, the South attempted to reduce the Negro to a position of peonage by the passage of the black codes. Many northern men led by Sumner and Stevens, who at first tried to secure the cooperation of the best whites, became indignant because of this attitude of the South and were reduced to the necessity of forcing Negro suffrage upon the South at the point of the bayonet, believing that the only way to insure the future welfare of the Negro was to safeguard it by giving him the ballot. Under the protection of these military governments, the Negroes and certain more or less fortunate whites gained political control. The southern white men, weary and disgusted because of the outcome of their attempts at secession, maintained an attitude of sullenness and indifference toward the new regime and accordingly offered at first very little opposition to the Negro control of politics. The Negroes, upon their securing the right of suffrage, however, turned at once to their former masters for political leadership,651 but the majority of these southern gentlemen refused to "lower their dignity" by political association with the Negroes. The few southern gentlemen who did affiliate with the Negroes were dubbed "scalawags" by their former friends and cast out of southern society.

The Negroes were then forced, because of the lack of cooperation on the part of the southern whites, to accept the leadership of certain northern men who came South for the sole purpose of personal gain and exploitation. These men were in some cases of an extremely low order and were in a large measure responsible for the corruption of Reconstruction days. They were contemptuously called "carpetbaggers" by the southern whites because they were so poor that they could carry all of their possessions in a carpet bag. Some of these white men were conscientious, however, and served these States honorably. Most Negroes, therefore, were under the leadership of these three elements: southern men who were regarded by their neighbors as men of the lowest possible order, unscrupulous adventurers from the North, and some intelligent members of their own race like B. K. Bruce, John R. Lynch, R. B. Elliot, and John M. Langston. This ill-assorted group of politicians reconstructed the Southern States.

The wisdom of this policy has been widely questioned. From the point of view of most white men studying Reconstruction history this effort to make the Negro a factor in politics was a failure, the elimination of the Negro from politics was just, and the rise of the Negro to political power even today is viewed with alarm. The opinions of the biased historians in this field will be interesting. Several writers refer to the Negro carpet bag movement as an effort to found commonwealths upon the votes of an ignorant Negro electorate, as working an injustice both to the whites and the blacks in that it made the South solidly democratic.652 J. G. de R. Hamilton, exaggerating the actual basis of Reconstruction in the southern commonwealths, which were never fully controlled by the Negroes, speaks of the work as having left as a legacy "a protest against anything that might threaten a repetition of the past, when selfish politicians, backed up by the Federal Government, for party purposes, attempted to Africanize the State and deprive the people through misrule and oppression of most that life held dear."653 John W. Burgess calls the effort an "extravagant humanitarianism which had developed in the minds of the Reconstruction leaders to the point of justifying, not only the political equality of the races but the political superiority at least in loyalty to the Union, the constitution and republican government, of the uncivilized Negroes of the South."654 Burgess sees justice in subjecting the inferior to the superior class but none in subjecting the superior to the inferior.