Полная версия

Полная версияThe Bay State Monthly. Volume 1, No. 1, January, 1884

"No. How is that done?" I asked.

"O! there's ever so many! One is, you pick two of them big thistles 'fore they are bloomed out, then you name 'em and put 'em under your piller; the one that blooms out fust will be the one you will marry. 'Nuther one is to walk down cellar at twelve o'clock at night, backwards, with a looking-glass in your hand. You will see your man's face in the glass. But there! I don't know as its best to act so. You know how Foster got sarved?"

"No. How was it?"

"Why! Didn't you never hear? Well, Foster told the Devil if he would let him do and have all he wanted for so many year, when the time was out, he would give himself, soul and body, to the Devil. He signed the writing with his blood; Foster carried on a putty high hand, folks was afear'd of him. When the time was up, the Devil came: I guess they had a tough battle. Folks said they never heard such screams, and in the morning his legs and arms was found scattered all over the cowyard."

I recognized in this tragic story, Marlowe's Faustus. I was much amused at Lucy's rendering.

A few weeks afterwards she told me how the house where she lived was haunted. I asked her, "Who haunts it?"

"Why!" she said, "it's a woman. She walks up and down them old stairs, dressed in white, looking so sorrowfullike, I know there must have been foul play. And then such noises as we hear overhead! My man says that it's rats. Rats! I know better!"

I thought that Lucy wanted to believe in ghosts, so I didn't try to reason with her,—

"For a man convinced against his willIs of the same opinion still."Lucy was quite an old woman; and I used to think that washing was too hard work for her; but she seemed very happy. All the while she was rubbing the clothes over the wooden washboard, or wringing them out with her hands, she would be singing old-fashioned songs, such as Jimmy and Nancy, Auld Robin Gray, and another one beginning "In Springfield mountain there did dwell." It was very sad!

These songs were chanted, all in one tune. If the words had not been quaint, and suggestive of a century or more ago, I think the entertainment would have been monotonous,

Lucy brought the news of the neighborhood. One morning she came in, and said: "John King's folks thinks an awful sight of themselves, sence Calline has been off. She has sot herself up marsterly. They have gone to work now and painted all the trays and paint-kags they can find red, and filled them with one thing another, and set them round the house. No good will come of that! When you see every thing painted red, look out for war; it's a sure sign."

One evening late in summer, when I came in from a walk through the fields, I found in the back porch all the implements for cheese-making. Mrs. Wetherell said: "It's too warm to make butter, now dog-days have come in, so I am going to make cheese."

That night all the milk was strained into the large tub. The next morning this milk was stirred and the morning's milk strained into it. Then Mrs. Wetherell warmed a kettleful and poured into the tub, and tried it with her finger to see if it was warm enough. She said: "My rennet is rather weak, so I have to use considerable."

After she had turned the rennet in, she laid the cheese-tongs across the tub, and spread a homespun tablecloth over it, and looking up to me, she said: "In an hour or so that will come."

I made it my business, when the hour was out, to be back in the porch. Mrs. Wetherell was stirring up the thick white curd, and dipping out the pale green whey, with a little wooden dish. After she had "weighed it," she mixed in salt thoroughly. She asked me to hand her her cheese-hoop and cloth, which were lying on the table behind me. She put one end of the cloth into the hoop and commenced filling it with curd, pressing it down with her hand. When it was nearly full she slipped up the hoop a little: "to give it a chance to press," she said. After this, she put the cheese between two cheese-boards, in the press, and began to turn the windlass-like machine, to bring the weights down.

"Now," said she, "I shall let this stay in press all day, then I shall put it in pickle for twenty-four hours. The next night I shall rub it dry with a towel, and put it up in the cheese-room. Now comes the tug-o'-war! I have to watch them close to keep the flies out."

The forerunners of autumn had already touched the hillsides, and my thoughts were turning homeward, when one Saturday morning Mr. Wetherell came in and said: "Miss Douglass, don't you want to ride up to the paster? I'm going up to salt the steers."

Mrs. Wetherell hastened to add: "Yes, you go; you hain't had a ride since you been here. Old Darby ain't fast, but he's good."

Eagerly I accepted the invitation, and in a few minutes we set off.

Darby was a great strong white horse, with minute brown spots all over him. Mr. Wetherell told me stories of all the people, as Darby shuffled by their houses, raising a big cloud of dust.

When we came to a sandy stretch of road, Mr. Wetherell said: "This is what we call the Plains. Here is where we used to have May trainings, years and years ago. Once they had a sham-fight, and I thought I should have died a-laughing. I was nothing but a boy. We always thought so much of the gingerbread we got at training; I used to save my money to spend on that day. Once, when I was about thirteen year old, a passel of us boys got together to talk over training. Jim Barrows said that old Miss Hammet (she lived over behind the hill there) had got a cake baked, with plums in it, for training, and was going to have five cents a slice for it. He said: 'Now, if the rest of you will go into the house and talk with her, I will climb into the foreroom window, and hook the cake out of the three-cornered cupboard.' We all agreed. I went in, and commenced to talk with the old woman; some of the boys leaned up against the door that opened into the foreroom. After a little while we went out and met Jim, down by the spring, and we ate the cake. Some way a-nother it didn't taste so good as we expected. There was an awful outscreech when she found it out. Jim was a mighty smart fellar. He married a girl from Cranberry Medder, and they went down East. I have heard that they were doing fust-rate."

After riding for some time through low, woody places, where the grass grew on each side of the horse's track, we came to the main traveled road. Thistles were blooming and going to seed, all on one stock. Flax-birds were flying among them filling the air with their sweet notes. Soon we turned into a lane, and came to the pasture-bars, Mr. Wetherell said: "You stay here with Darby, and I will drive the steers up to the bars, and salt them."

I got out of the wagon, and unchecked Darby's head, and led him up to a plot of white clover, to get a lunch. Nature seemed to have made an uneven distribution of foretop and fetlock in Darby's case, his foretop was so scanty and his fetlocks so heavy. A fringe of long hairs stood out on his forelegs from his body to his feet, giving him quite a savage look. As I looked down at his large flat feet, I felt glad that he didn't have to travel over macadamized roads.

I sat down on some logs which were lying at one side, and listened to the worms sawing away, under the bark.

Soon Mr. Wetherell came back with the steers, and dropped the salt down in spots. We watched them lick it up.

I asked Mr. Wetherell why those logs were left there.

"O, Bascom is a poor, shiftless kind of a critter. I s'pose the snow went off before he got ready to haul them to the mill; but if he had peeled them in June or July, they would have been all right; but now they will be about sp'iled by the worms."

Mr. Wetherell got Darby turned around after much backing and getting up, for the lane was narrow, and we started homeward.

As we rode slowly along, Mr. Wetherell asked me: "Have you ever been to the beach?"

I told him, "Yes, and I enjoyed it."

He said: "I always liked to go, but Mis' Wetherell has a dread of the water, ever since her brother Judson was drowned."

"Was he a sailor?" I asked.

"Yes, he was a sea-capt'n. He married a Philadelphy woman, and they sailed in the brig Florilla. She was wrecked on the coast of Ireland. She run on a rock, and broke her in two amidships. Her cargo was cotton, the bales floated in ashore, and formed a bridge for a second or so. The first mate and one of the sailors ran in on this bridge, but the next wave took them out and scattered them, and there was no way to save the rest. Judson and his wife, and all the crew, except the mate and one sailor, were all drowned. The mate stayed there for some time, and buried the bodies which washed ashore. He found Judson's body first, and had most given up finding his wife's, when one day she washed into a little cove, and he buried them side by side. He came here to our house, and told us all about it. It was awful. It completely upsot Mis' Wetherell. Her health has been poor for a good many year. She has bad neuralgy spells."

"Come, Darby, get up! you are slower than a growth of white oaks."

After several vigorous jerks, Darby started off at a long, swinging gait, and we soon reached home.

Only once more did I watch the sun go down behind the western hills, lighting them up with a flood of crimson light; while a tender, subdued gleam rested for a moment on the eastern summits, like the gentle kiss a mother gives her babe, when she slips him off her arm to have his nap.

THE BELLS OF BETHLEHEM

[On hearing them in the hill country of New Hampshire, September, 1880.]"The far-off sound of holy bells."How the sweet chimes this Sunday morn,'Mid autumn's requiem,Across the mountain valleys borne,—The bells of Bethlehem!"Come join with us," they seem to say,"And celebrate this hallowed day!"Our hearts leap up with glad accord—Judea's Bethlehem strain,That once ascended to the Lord,Floats back to earth again,As round our hills the echoes swellTo "God with us, Emanuel!"O Power Divine, that led the starTo Mary's sinless Child!O ray from heaven that beamed afarAnd o'er his cradle smiled!Help us to worship now with themWho hailed the Christ at Bethlehem!James T. Fields, in The Granite Monthly.

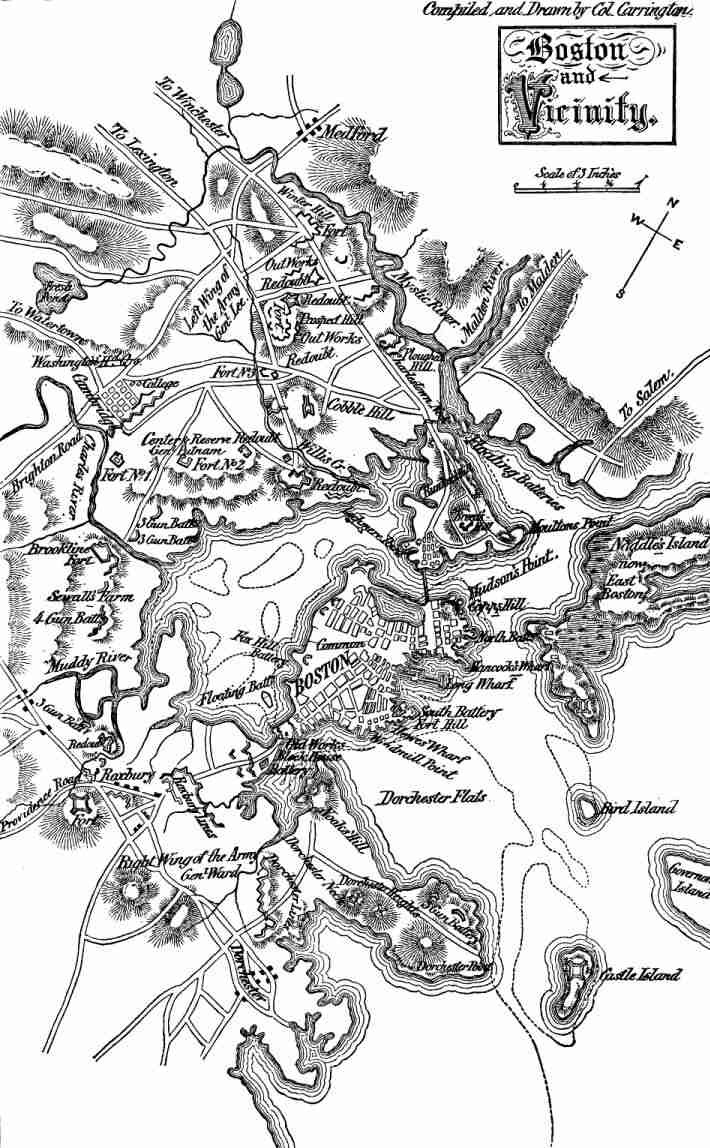

THE SIEGE OF BOSTON DEVELOPED

BY HENRY B. CARRINGTON, U.S.A., LL.D[Author of The Battles of the American Revolution, etc.]By order of the President of the United States, a national salute was fired, at meridian, on the twenty-fourth day of December, 1883, as a memorial recognition of the one hundreth anniversary of the surrender by George Washington, on the twenty-third day of December, 1783, at Annapolis, of his commission as commander-in-chief of the patriotic forces of America. This official order declares "the fitness of observing that memorable act, which not only signalized the termination of the heroic struggle of seven years for independence, but also manifested Washington's devotion to the great principle, that ours is a civil government, of and by the people."

The closing sentence of Washington's order, dated April 18, 1783, may well be associated with this latest centennial observance. As he directed a cessation of hostilities, his joyous faith, jubilant and prophetic, thus forecast the future: "Happy, thrice happy! shall they be pronounced, hereafter, who have contributed anything, who have performed the meanest office, in erecting this stupendous fabric of freedom and empire, on the broad basis of independence,—who have assisted in protecting the rights of human nature, and establishing an asylum for the poor and oppressed of all nations and religions."

The two acts of Washington, thus associated, were but the fruition of deliberate plans which were formulated in the trenches about Boston. The "centennial week of years," which has so signally brought into bold relief the details of single battles and has imparted fresh interest to many localities which retain no visible trace of the scenes which endear them to the American heart, has inclined the careless observer to regard the battles of the War for Independence as largely accidental, and the result of happy, or even of Providential, circumstances, rather than as the fruit of well-considered plans which were shaped with full confidence in success.

Battles and campaigns have been separated from their true relation to the war, as a systematic conflict, in which the strategic issue was sharply defined; and too little notice has been taken of the fact that Washington took the aggressive from his first assumption of command. The title "Fabius of America" was freely conferred upon him after his success at Trenton; but there was a subtle sentiment embodied in that very tribute, which credited him with the political sagacity of the patriot and statesman, more than with the genius of a great soldier. All contemporaries admitted that he was judicious in the use of the resources placed at his command, that he was keen to use raw troops to the best possible disposal, and took quick advantage of every opportunity which afforded relief to his poorly-fed and poorly-equipped troops, in meeting the British and Hessian regulars; but there were few who penetrated his real character and rightly estimated the scope of his strategy and the sublime grandeur of his faith.

The battles of that war (each is its place) have had their immediate results well defined. To see, as clearly their exact place in relation to the entire struggle, and that they were the legitimate sequence of antecedent preparation, requires that the preparation itself shall be understood.

The camps, redoubts, and trenches, which engirdled Boston during its siege, were so many appliances in the practical training-school of war, which Washington promptly seized, appropriated, and developed. The capture of Boston was not the chief aim of Washington, when, on the third day of July, 1775, he established his headquarters at Cambridge. Boston was, indeed, the immediate objective point of active operations, and the issue, at arms, had been boldly made at Lexington and Concord. Bunker Hill had practically emancipated the American yeomanry from the dread of British arms, and foreshadowed the finality of National Independence. However the American Congress might temporize, there was not alternative with Washington, but a steady purpose to achieve complete freedom. From his arrival at Cambridge, until his departure for New York, he worked with a clear and serene confidence in the final result of the struggle. A mass of earnest men had come together, with the stern resolve to drive the British out of Boston; but the patriotism and zeal of those who first begirt the city were not directed to a protracted and universal colonial resistance. To the people of Massachusetts there came an instant demand, imperative as the question of life or death, to fight out the issue, even if alone and single-handed, against the oppressor. Without waiting for reports from distant colonies as to the effect of the skirmish at Lexington and the more instructive and stimulating experience at Breed's Hill, the penned the British in Boston and determined to drive them from the land. Dr. Dwight said of Lexington: "The expedition became the preface to the history of a nation, the beginning of an empire, and a theme of disquisition and astonishment to the civilized world."

The battle of Bunker Hill equalized the opposing forces. The issue changed from that of a struggle of legitimate authority to suppress rebellion, and became a context, between Englishmen, for the suppression, or the perpetuation, of the rights of Magna Charta.

The siege of Boston assumed a new character as soon as it became a part of the national undertaking to emancipate the Colonies, on and all, and thereby establish one great Republic.

From the third of July, 1775, until the seventeenth of March, 1776, there was gradually developed a military policy with an army system, which shaped the whole war.

Many battles have been styled "decisive." many slow tortures of the oppressed have prepared the way for heroic defiance of the oppressor. Many elaborate preparations have been made for war, when at last some sudden outrage or event has precipitated and unlooked-for conflict, and all preparations, however wisely adjusted, have been made in vain. "I strike to-night!" was the laconic declaration of Napoleon III, as he informed his proud and beautiful empress, that "the battalions of France were moving on the Rhine." The march of Lord Percy to Concord was designed to clip off, short, the seriously impending resistance of the people to British authority. With full recognition of all that had been done, before the arrival of Washington to assume command of the besieging militia, as the "Continental Army" of America, there are facts which mark the months of that siege, as months of that wise preparation which ensured the success of the war. Washington at once took the offensive. He was eminently aggressive; but neither hasty nor rash. Baron Jomini said that "Napoleon discounted time." So did Washington. Baron Jomini said, also, that "Napoleon was his own best chief-of-staff." So, pre-eminently, was Washington.

The outlook at Cambridge, on the third of July, 1775, revealed the presence of a host of hastily-gathered and rudely-armed, earnest men, well panoplied, indeed, in the invulnerable armor of loyalty to country and to God; fearless, self-sacrificing, daring death to secure liberty; but lacking that discipline, cohesion, and organized assignment to place and duty, which convert a mass of men into an army of soldiers. Washington stated the case, fairly, in the terse expression: "They have been accustomed, officers and men alike, to have their own way too long already."

The rapidly succeeding methods through which that mass of fiery patriots became a well-ordered army, obedient to authority, and accepting the delays and disappointments of war with cheerful submission, will stand as the permanent record of a policy which cleared the way for an assured liberty.

As early as 1775, Lord Dartmouth had asserted, with vigor, that Boston was worthless as a base, if the authority of the Crown was to be seriously defied by the colonies, acting in concert. He advocated the evacuation of Boston, and the consolidation of the royal forces at New York. Washington, early after his arrival at Cambridge, saw that the British commander had made a mistake. His letters to Congress are full of suggestions which citizens could only slightly value, so long as they saw Boston still under British control. It is difficult to see how the war could have been a success, if New York had been occupied, in force, by Lord Howe in 1775, and the rashness of Gates had not precipitated the skirmish at Lexington and the battle of Bunker Hill. It is no less hard to see where and how Washington could have found time, place, and suitable conditions for that practical campaign experience which the siege of Boston afforded.

The mention of some of these incidents will suggest others, and illustrate that experience.

A practical siege was undertaken, under the most favorable circumstances. The whole country, near by, was in sympathy with the army. The adjacent islands, inlets, and bays swarmed with scouting parties, which cut off supplies from the city. The army had its redoubts and trenches, and the heights of Bunker Hill were in sight as a pledge of full ability to resist assault. As a fact, no successful sortie was made out of Boston during the siege; but constant activity and watchfulness were vital to each day's security. Provisions were abundant and the numerical strength was sufficient. System and discipline alone were to be added.

The details of camp life in the immediate presence of skilled enemies compelled officers and men, alike, to learn the minutest details of field engineering. Gabions, fasces, abattis, and other appliances for assault or defence were quickly made, and all this practical schooling in the work of war went on, under the watchful cooperation of the very officers who afterward became conspicuous in the field, from Long Island to Yorktown. THE CAMP ABOUT BOSTON MADE OFFICERS, Its discipline dissipated many colonial jealousies; and there was developed that confidence in their commander, which, in after years, became the source of untold strength and solace to him in the darkest hours of the war.

The details of the personal work of the commander-in-chief read more like some magician's tale. Every staff department was organized under his personal care, so that he was able to retain even until the end of the war his chief assistants. Powder, arms, provisions, clothing, firewood, medicines, horses, carts, tools, and all supplies, however incidental, depended upon minute instructions of Washington himself.

A few orders are cited, as an illustration of the system which marked his life in camp, and indicate the value of those months, as preparatory to the ordeal through which he had yet to pass.

To withhold commissions, until some proof was given of individual fitness, involved grave responsibility. He did it. To punish swearing, gambling, theft, and lewdness, evinced a high sense of the solemnity of the hour. He did it. To rebuke Protestants for mocking Catholics was to recognize the dependence of all alike upon the God of battles. He did it. To repress gossip in camp, because the reputation of the humblest was sacred; to brand with his displeasure all conflicts between those in authority, as fatal to discipline and unity of action, and to forbid the settlement of private wrongs except through established legal methods, showed a clear conception of the conditions which would make an army obedient, united, and invincible. These, and corresponding acts in the line of military police regulations, and touching every social, moral, and physical habit which assails or enfeebles a soldier's life and imperils a campaign, run through his papers.

It is in the light of such omnipresent pressure and constraint that we begin to form some just estimate of the relations which the siege of Boston sustained to the subsequent operations of the war, and to the work of Lee, Putnam, Sullivan, Greene, Mifflin, Knox, and others, who were thus fitted for immediate service at Long Island and elsewhere, as soon as Boston was evacuated.

It is also through these orders that the careful student can pass that veil of formal propriety, reticence, and dignity which so often obscured the inner, the tentative, elements of Washington's military character.

While the slow progress of the siege afforded opportunity to study the contingencies of other possible fields of conflict, a double campaign was made into Canada: namely, by Arnold through Maine, and by Montgomery toward Montreal. This was based upon the idea that the conquest of Canada would not only protect New England on the north, but compel the British commanders to draw all supplies from England. The fact is noted, as evidence of the constant regard which the American commander had for every exposed position of the enemy which could be threatened, without neglecting the demands of the siege itself. Frequent attempts were made to force the siege to an early conclusion. The purpose was to expel or capture the garrison before Great Britain could send another army, and open active operations in other colonies, and not, merely in the indolence of the mere watchdog, to starve the enemy into terms. "Give me powder or ice, and I will take Boston," was the form in which Washington demanded the means of bombardment or assault, and gave the assurance that, if the river would freeze, he would force a decisive issue with the means already at command.

Meanwhile, he sent forth privateers to scour the coast and search for vessels conveying powder to the garrison; and soon no British transport or supply-vessel was secure, unless under convoy of a ship-of-war.

At last, Congress increased the army to twenty-four thousand men and ordered a navy to be built. Washington redoubled his efforts, confident that Boston was substantially at his mercy; but seeing as clearly that the capture or the evacuation of the city would introduce a more general and desperate struggle, and one that would try his army to the most.

At this juncture, General Howe was strongly reinforced. When he succeeded Gates, on the tenth of October, 1775, he "assumed command of all his Britannic Majesty's forces, from Nova Scotia to Florida," and thus indicated his appreciation of the possible extent of the American resistance. It was a fair response to the claim of Washington to represent "The Colonies, in arms." Howe's reinforcements had reported for duty by the thirty-first of December. During the preceding months, and, in fact, from his arrival at Cambridge, Washington had freely conferred with General Greene. That young officer had studied Caesar's Commentaries, Marshal Turenne's Works, Sharp's Military Guide, and many legal and standard works upon government and history, while drilling a militia company, the Kentish Guards, and following the humble labor of a blacksmith's apprentice. He fully appreciated the value of the hours spent before Boston. Together with General Sullivan, who, as well as himself, commanded a brigade in Lee's division, he looked beyond the lines of the camp rear-guard, and spent extra hours in discipline and drill, to bring his own command up to the highest state of proficiency.