Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Notes and Queries, Number 186, May 21, 1853

In 1639, English comedians are again found in Koningsberg; and, for the last time, in 1650, at Vienna, where William Roe, John Waide, Gideon, Gellius, and Robert Casse, obtained a license from Ferdinand I.

In 1620 appeared a volume of Englische Comedien und Tragedien, &c. (2nd edit., 1624), which was followed by a second; and in 1670 by a third: in which last, however, the English element is not so prominent.

These statements of Dr. Hagen are confirmed by numerous quotations from original documents, published by him in the Neue Preuss. Provincial Blätter, Koningsb., 1850, vol. x.; vid. et Gesch. der Deuts. Schauspielk., by E. Devrient, Leipzic, 1848. Professor Hagen maintains, that in the beginning of the seventeenth century, the English comedies were performed in Dutch; and that, in Germany, the same persons were called indifferently English or Dutch comedians. They were Englishmen who had found shelter under the English trading companies in the Netherlands ("Es waren Engländer die in den englischen Handelscompagnien in den Niederlanden ein Unterkommen gefunden.")—From the Navorscher.

J. M.A GENTLEMAN EXECUTED FOR WHIPPING A SLAVE TO DEATH

(Vol. vii., p. 107.)The occurrence noticed by W. W. is, I believe, the only instance on record in the West Indies of the actual execution of a gentleman for the murder, by whipping or otherwise, of a slave. Nor is this strange. In the days of slavery every owner of slaves was regarded in the light of a gentleman, and his "right to do what he liked with his own" was seldom called in question by judges or juries, who were themselves among the principal shareholders. The case of Hodge was, however, of an aggravated character. For the trivial offence of stealing a mango, he had caused one of his slaves to be whipped to death; and this was, perhaps, the least shocking of the repeated acts of cruelty which he was known to have committed upon the slaves of his estate.

During slavery each colony had its Hodge, and some had more than one. The most conspicuous character of this kind in St. Lucia was Jacques O'Neill de Tyrone, a gentleman who belonged to an Irish family, originally settled in Martinique, and who boasted of his descent from one of the ancient kings of Ireland. This man had long been notorious for his cruelty to his slaves. At last, on the surrender of the colony to the British in 1803, the attention of the authorities was awakened; a charge of murder was brought against him, and he was sentenced to death. From this sentence he appealed to a higher court; but such was the state of public feeling at the bare idea of putting a white man to death for any offence against a slave, that for a long time the members of the court could not be induced to meet; and when they did meet, it was only to reverse the sentence of the court below. I have now before me the proceedings of both courts. The sentence of the inferior court, presided over by an European judge, is based upon the clearest evidence of O'Neill's having caused two of his slaves to be murdered in his presence, and their heads cut off and stuck upon poles as a warning to the others. The sentence of the Court of Appeal, presided over by a brother planter, and entirely composed of planters, reverses the sentence, without assigning any reason for its decision, beyond the mere allegations of the accused party. Such was criminal justice in the days of slavery!

Henry H. Breen.St. Lucia.

LONGEVITY

(Vol. vii., p. 358., &c.)On looking over some volumes of the Annual Register, from its commencement in 1758, I find instances of longevity very common, if we can credit its reports. In vol. iv., for the year 1761, amongst the deaths, of which there are many between 100 and 110, the following occur:

January. "At Philadelphia, Mr. Charles Cottrell, aged 120 years; and three days after, his wife, aged 115. This couple lived together in the marriage state 98 years in great union and harmony."

April. "Mrs. Gillam, of Aldersgate Street, aged 113."

July. "John Newell, Esq., at Michael(s)town, Ireland, aged 127, grandson to old Parr, who died at the age of 152."

August. "James Carlewhite, of Seatown, in Scotland, aged 111.

"John Lyon, of Bandon, in the county of Cork, Ireland, aged 116."

In September there are three aged 106; one 107; one 111; one 112; and one 114 registered. I will take three from the year 1768, viz.:

January. "Died lately in the Isle of Sky, in Scotland, Mr. Donald McGregor, a farmer there, in the 117th year of his age.

"Last week, died at Burythorpe, near Malton in Yorkshire, Francis Confit, aged 150 years: he was maintained by the parish above sixty years, and retained his senses to the very last."

April. "Near Ennis, Joan McDonough, aged 138 years."

Should sufficient interest attach to this subject, and any of the correspondents of "N. & Q." wish it, I will be very happy to contribute my mite, and make out a list of all the deaths above 120 years, or even 110, from the commencement of the Annual Register, but am afraid it will be found rather long.

J. S. A.Old Broad Street.

A few years ago there lived in New Ross, in the county of Wexford, two old men. The one, a slater named Furlong, a person of very intemperate habits, died an inmate of the poorhouse in his 101st year: he was able to take long walks up to a very short period before his death; and I have heard that he, his son, and grandson, have been all together on a roof slating at the same time. The other man was a nurseryman named Hayden, who died in his 108th year: his memory was very good as to events that happened in his youth, and his limbs, though shrunk up considerably, served him well. He was also in the frequent habit of taking long walks not long before his death.

J. W. D.DERIVATION OF CANADA

(Vol. vii., p. 380.)The derivation given in the "cutting from an old newspaper," contributed by Mr. Breen, seems little better than that of Dr. Douglas, who derives the name from a M. Cane, to whom he attributes the honour of being the discoverer of the St. Lawrence.

In the first place, the "cutting" is not correct, in so far as Gaspar Cortereal never ascended the river, having merely entered the gulf, to which the name of St. Lawrence was afterwards given by Jacques Carter. Neither was the main object of the expedition the discovery of a passage into the Indian Sea, but the discovery of gold; and it was the disappointment of the adventurers in not finding the precious metal which is supposed to have caused them to exclaim "Aca nada!" (Nothing here).

The author of the Conquest of Canada, in the first chapter of that valuable work, says that "an ancient Castilian tradition existed, that the Spaniards visited these coasts before the French,"—to which tradition probably this supposititious derivation owes its origin.

Hennepin, who likewise assigns to the Spaniards priority of discovery, asserts that they called the land El Capo di Nada (Cape Nothing) for the same reason.

But the derivation given by Charlevoix, in his Nouvelle France, should set all doubt upon the point at rest; Cannáda signifying, in the Iroquois language, a number of huts (un amas de cabanes), or a village. The name came to be applied to the whole country in this manner:—The natives being asked what they called the first settlement at which Cartier and his companions arrived, answered, "Cannáda;" not meaning the particular appellation of the place, which was Stadacóna (the modern Quebec), but simply a village. In like manner, they applied the same word to Hochelága (Montreal) and to other places; whence the Europeans, hearing every locality designated by the same term, Cannáda, very naturally applied it to the entire valley of the St. Lawrence. It may not here be out of place to notice, that with respect to the derivation of Quebec, the weight of evidence would likewise seem to be favourable to an aboriginal source, as Champlain speaks of "la pointe de Québec, ainsi appellée des sauvages;" not satisfied with which, some writers assert that the far-famed city was named after Candebec, a town on the Seine; while others say that the Norman navigators, on perceiving the lofty headland, exclaimed "Quel bec!" of which they believe the present name to be a corruption. Dissenting from all other authorities upon the subject, Mr. Hawkins, the editor of a local guide-book called The Picture of Quebec, traces the name to an European source, which he considers to be conclusive, owing to the existence of a seal bearing date 7 Henry V. (1420), and on which the Earl of Suffolk is styled "Domine de Hamburg et de Québec."

Robert Wright.SETANTIORUM PORTUS

(Vol. vii., pp. 180. 246.)Although the positions assigned by Camden to the ancient names of the various estuaries on the coasts of Lancashire and Cumberland are very much at variance with those laid down by more modern geographers; still, with regard to the particular locality assigned by him to the Setantiorum Portus, he has made a suggestion which seems worthy the attention of your able correspondent C.

His position for Morecambe Bay is a small inlet to the south of the entrance of Solway Firth, into which the rivers Waver and Wampool empty themselves, and on which stands "the abbey of Ulme, or Holme Cultraine." He derives the name from the British, as signifying a "crooked sea," which doubtless is correct; we have Môr taweh, the main sea; Morudd, the Red Sea; and Môr camm may be supposed to indicate a bay much indented with inlets. It is needless to say that the present Morecambe Bay answers this description far more accurately than that in the Solway Firth. Belisama Æstuarium he assigns to the mouth of the Ribble, and is obliged to allot Setantiorum Portus to the remaining estuary, now called Morecambe Bay. However, he seems not quite satisfied with this last arrangement, and suggests that it would be more appropriate if we might read, as is found in some copies, Setantiorum λίμνη, instead of λιμὴν, thus assigning the name of Setantii to the inhabitants of the lake district.

The old editions of Ptolemy, both Greek and Latin, are very incorrect, and, there is little doubt, have suffered from alterations and interpolations at the hands of ignorant persons. I have not access at present to any edition of his geography, either of Erasmus, Servetus, or Bertius, so I know not whether any weight should be allowed to the following circumstance; in the Britannia Romana, in Gibson's Camden, this is almost the only Portus to be found round the coast of England. The terms there used are (with one more exception) invariably æstuarium, or fluvii ostium. If this variation in the old reading be accepted, the appellation as given by Montanus, Bertius, and others, to Winandermere, becomes more intelligible.

H. C. K.—– Rectory, Hereford.

PHOTOGRAPHIC CORRESPONDENCE

Stereoscopic Queries.—Can any of your readers inform me what are the proper angles under which stereoscopic pictures should be taken?

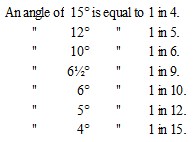

Mr. Beard, I am informed, takes his stereoscopic portraits at about 6½°, or 1 in 9; that is to say, his cameras are placed 1 inch apart for every 9 inches the sitter is removed from them. The distance of the sitter with him is generally, I believe, 8 feet, which would give 10⅔ inches for the extent of the separation between his cameras. More than this has the effect, he says, of making the pictures appear to stand out unnaturally; that is to say, if the cameras were to be placed 12 inches apart (which would be equal to 1 in 8), the pictures would seem to be in greater relief than the objects.

I find that the pictures on a French stereoscopic slide I have by me have been taken at an angle of 10°, or 1 in 6. This was evidently photographed at a considerable distance, the triumphal arch in the Place de Carousel (of which it is a representation) being reduced to about 1¼ inch in height. How comes it then that the angle is here increased to 10° from 6½°, or to 1 in 6 from 1 in 9.

Moreover, the only work I have been able to obtain on the mode of taking stereoscopic pictures, lays it down that all portraits, or near objects, should be taken under an angle of 15°, or, as it says, 1 in 5; that is, if the camera is 20 feet from the sitter, the distance between its first and second position (supposing only one to be used) should not exceed 4 feet: otherwise, adds the author, "the stereosity will appear unnaturally great."

When two cameras are employed, the instructions proceed to state that the distance between them would be about 1/10th of the distance from the part of the object focussed. The example given is a group of portraits, and the angle, 1 in 10, is afterwards spoken of as being equivalent to an arc of 10°.

Farther on, we are told that "the angle should be lessened as the distance between the nearest and farthest objects increase. Example: if the farthest object be twice as far from the camera as the near object, the angle should be 5° to a central point between these two.

Now, I find by calculation that the measurements and the angle here mentioned by no means agree. For instance, an angle of 15° is spoken of as being equivalent to the measurement 1 in 5. An angle of 10° is said, or implied, to be the same as 1 in 10. This is far from being the fact. According to my calculations, the following are the real equivalents:—

Will any of your readers oblige me by solving the above anomalies, and by giving the proper angles or measurement under which objects should be taken when near, moderately distant, or far removed from the camera; stating, at the same time, at how many feet from the camera an object is to be considered as near, or distant, or between the two? It would be a great assistance to beginners in the stereoscopic art, if some experienced gentleman would state the best distances and angles for taking busts, portraits, groups, buildings, and landscapes.

It is said that stereoscopic pictures at great distances, such as views, should be taken "with a small aperture." But as the exact dimensions are not mentioned, it would be equally serviceable if, to the other details, were added some account of the dimensions of the apertures required for the several angles.

In the directions given in the work from which I have quoted, it is said that when pictures are taken with one camera placed in different positions, the angle should be 15°; but when taken with two cameras, the angle should be 10°. Is this right? And, if so, why the difference?

In the account given by you of Mr. Wilkinson's ingenious mode of levelling the cameras for stereoscopic pictures, it is said the plumb-line should be three feet long, and that the diagonal lines drawn on the ground glass should be made to cut the principal object focussed on the glass; and "when you have moved it, the camera, 8 or 10 feet, make it cut the same object again." At what distance is the object presumed to be?

Any information upon the above matters will be a great service, and consequently no slight favour conferred upon your constant reader since the photographic correspondence has been commenced.

φ.Photographic Portraits of Criminals, &c.—Such experience as I have had both in drawing portraits and taking photographs, impels me to hint to the authorities of Scotland Yard that they will by no means find taking the portraits of gentlemen that are "wanted" infallible, and I anticipate some unpleasant mistakes will ere long arise. I have observed that inability to recognize a portrait is as frequent in the case of photographs as on canvass, or in any other way. I defy the whole world of artists to reduce the why and wherefore into a reasonable shape; one will declare that "either" looks as if the individual was going to cry; the next critic will say he sees nothing but a pleasant smile. "I should never have known who it is if you hadn't told me," says a third; the next says "it's his eyes, but not his nose;" and perhaps the next will say, "it's his nose, but not his eyes."

I was present not long since at the showing a portrait, which I think about the climax of doubt. "Not a bit like," was the first exclamation. The poor artist sank into his chair; after, however, a brief contemplation, "It's very like, in-deed; it's excellent:" this was said by a gentleman of the highest attainments, and one of the best poets of the day.

Some persons (I beg pardon of the ladies) take the habiliments as the standard of recognition. I do not accuse them of doing it wilfully; they do not know it themselves. For example, Miss Smith will know Miss Jones a mile or so off. By her general air, or her face? Oh no! It's by the bonnet she helped her to choose at Madame What-d'ye-call's, because the colour suited he complexion.

These are some of the mortifications attendant on artistic labour, and if they occur with the educated classes, they are more likely to happen even to "intelligent policemen," as the newspaper have it. If I dissent from the plan it is because I doubt its efficiency, but do not deny that it is worth a trial. If the French like to carry their portraits about with them on their passports to show to policemen, let them submit to the humiliation. I doubt very much whether the Chamber of Deputies would have made a law of it: it appears a new idea in jurisprudence that a man must sit for his picture. Any one, however, understanding the camera, would be alive before the removal of the cup of the lens, and be ready with a wry face; I do not suppose he could be imprisoned for that.

Both plans are miserable travesties on the lovely uses of portrait painting and photography. Side by side with Cowper's passionate address to his mother's picture, how does it look?

"Oh, that those lips had language! Life has pass'dWith me but roughly since I saw thee last."And,

"Blest be the art that can immortalise."If photography has an advantage over canvas, it does indeed immortalise (the painting may imitate, and the portrait may be good; but there is something more profoundly affecting in having the actual, the real shade of a friend perhaps long since in his grave); and we ought not only to be grateful to the illustrious inventors of the art, but prevent these base uses being made of it.

In short, apart from the uncertainty of recognition, which I have not in the least caricatured, if Giles Scroggins, housebreaker and coiner, and all the swell mob, are to be photographed, it will bring the art into disgrace, and people's friends will inquire delicately where it was done, when they show their lively effigies. It may also mislead by a sharp rogue's adroitness; and I question very much its legality.

Weld Taylor.Photography applied to Catalogues of Books.—May not photography be usefully applied to the making of catalogues of large libraries? It would seem no difficult matter to obtain any number of photographs, of any required size, of the title-page of any book. Suppose the plan adopted, that five photographs of each were taken; they may be arranged in five catalogues, as follows:—Era, subject, country, author, title. These being arranged alphabetically, would form five catalogues of a library probably sufficient to meet the wants of all. Any number of additional divisions may be added. By adopting a fixed breadth—say three inches—for the photographs, to be pasted in double columns in folio, interchanges may take place of those unerring slips, and thus librarians aid each other. I throw out this crude idea, in the hope that photographers and librarians may combine to carry it out.

Albert Blor, LL.D.Dublin.

Application of Photography to the Microscope.—May I request the re-insertion of the photographic Query of R. J. F. in Vol. vi., p. 612., as I cannot find that it has received an answer, viz., What extra apparatus is required to a first-rate microscope in order to obtain photographic microscopic pictures?

J.Replies to Minor Queries

Discovery at Nuneham Regis (Vol. vi., p. 558.).—May the decapitated body, found in juxta-position with other members of the Chichester family, not be that of Sir John Chichester the Younger, mentioned in Burke's Peerage and Baronetage, under the head "Chichester, Sir Arthur, of Raleigh, co. Devon," as being that fourth son of Sir John Chichester, Knt., M.P. for the co. Devon, who was Governor of Carrickfergus, and lost his life "by decapitation," after falling into the hands of James Macsorley Macdonnel, Earl of Antrim?

The removal of the body from Ireland to the resting-place of other members of the family would not be a very improbable event, and quite consistent with the natural affection of relatives, under such mournful circumstances.

J. H. T.Eulenspiegel, or Howleglas (Vol. vii., pp. 357. 416.).—Permit me to acquaint your correspondent that among the many singular and curious books which formed the library of that talented antiquary the late Charles Kirkpatrick Sharp, and which were sold here by auction some time ago, there was a small 12mo. volume containing French translations, with rude woodcuts, of—

1. "La Vie joyeuse et recreative de Tiel-Ullespiegle, de ses Faits merveilleux et Fortunes qu'il a eues; lequel par aucune Ruse ne se laissa pas tromper. A Troyes, chez Garner, 1838."

2. "Histoire de Richard Sans Peur, Duc de Normandie, Fils de Robert le Diable, &c. A Troyes, chez Oudot, 1745."

T. G. S.Edinburgh.

Parochial Libraries (Vol. vi., p. 432.; Vol. vii., pp. 193. 369. 438.).—

"In the year 1635, upon the request of the Rev. Anthony Tuckney, Vicar of Boston, it was ordained by the Archbishop of Canterbury (Laud), then on his metropolitical visitation at Boston, 'that the roome over the porch of the saide churche shall be repaired and decently fitted up to make a librarye, to the end that, in case any well and charitably disposed person shall hereafter bestow any books to the use of the parish, they may be there safely preserved and kept.'"

This library at present contains several hundred volumes of ancient (patristic, scholastic, and post-Reformation) divinity.

I hope to be able ere long to make a correct catalogue of the books at present remaining, and at the same time make an attempt to restore them to that decent "keeping" in which the great and good archbishop desired they might remain.

Query: In making preparations for the catalogue, I have been informed by a gentleman that he remembers two or more cart loads of books from this library being sold by the churchwardens, and, as he believes, by the then archdeacon's orders, at waste paper price; that the bulk of them was purchased by a bookseller then resident in Boston, and re-sold by him to a clergyman in the neighbourhood of Silsby.

1. What was the date of the sale?

2. The name of the Venerable Archdeacon who perpetrated this robbery?

3. Whether there are any legal means for recovering the missing works?

My extracts are from Thompson's History of Boston, a correspondent of yours, a new edition of whose laborious work is about to appear.

Thomas Collis.Boston.

Painter—Derrick (Vol. vii., pp. 178. 391.).—I cannot agree with J. S. C. that painter is a corruption of punter, from the Saxon punt, a boat. According to the construction and analogy of our language, a punter or boater would be the person who worked or managed the boat. I consider that painter—like halter and tether, derived from Gothic words signifying to hold and to tie—is a corruption of bynder, from the Saxon bynd, to bind. If the Anglo-Norman word panter, a snare for catching and holding birds, be a corruption of bynder, we are brought to the word at once. Or, indeed, we may go no farther back than panter.

J. C. G. says that derrick is an ancient British word: perhaps he will be kind enough to let us know its signification. I always understood that a derrick took its name from Derrick, the notorious executioner at Tyburn, in the early part of the seventeenth century, whose name was long a general term for hangman. In merchant ships, the derrick, for hoisting up goods, is always placed at the hatchway, close by the gallows. The derrick, however, is not a nautical appliance alone; it has been long used to raise stones at buildings; but the crane, and that excellent invention the handy-paddy, has now almost put it out of employment. What will philologists, two or three centuries hence, make out of the word handy-paddy, which is universally used by workmen to designate the powerful winch, traversing on temporary rails, employed to raise heavy weights at large buildings. For the benefit of posterity, I may say that it is very handy for the masons, and almost invariably worked by Irishmen.