Полная версия

Полная версияLippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. XVI., December, 1880.

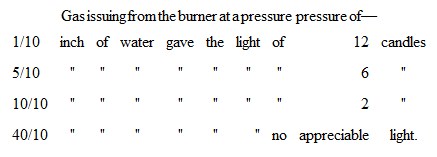

"With these lamps the pressure of the gas-current is of great importance; and I now turn to that subject. It is a general complaint in buildings whose rooms are high that the flow of gas on the lower floor is deficient, while on the upper floors there is a greater supply than is necessary. This inconvenience arises from the upper stories being subjected to less atmospheric pressure than the lower, every rise of ten feet making a difference in the pressure of about one-tenth of an inch of water; and, consequently, a column of gas acquires that amount of pressure additional. The following table, recording an experiment of Mr. Richards, will show the result in respect to light:

Suppose a building of six floors is supplied from the gas-mains at a pressure of six-tenths, and that the difference of altitude between the highest and lowest light is equal to fifty feet: the gas in the highest or sixth floor will issue from the burners at a pressure of eleven-tenths; the fifth floor, at ten-tenths; and so on. In order to secure an entirely equable flow and economical light a regulator is necessary on each floor above the first. The gas companies are frequently obliged to supply mills at a much greater pressure than is stated above as necessary, in order that the ground floors may have sufficient light."

"How about incorrect meters?" asked the traveller.

"Little need be said of them, as they fall within the domain of the companies and the public inspector of gas. Under favorable conditions gas-meters will remain in order for ten years or more; and when they become defective they as often favor the consumer, probably, as they do the gas company. Their defects do not often occasion inconvenience; and when they once get out of order they run so wild that their condition is soon detected, when the errors in previous bills should be corrected by estimate of other seasons."

"You haven't mentioned the apparatus (carburetters) for increasing the richness of the gas, which can be applied by the consumer upon his own premises," said the old gentleman.

"There is little need. The burners should be adjusted to the quality of gas furnished. If there were any real gain in this method of enrichment, the gas companies are the parties who could make the most of it: indeed, many of them do to such an extent as can be made profitable. But whenever the temperature of the atmosphere falls, the matter added to the gas is deposited in the pipes, sometimes choking them entirely at the angles. No: arrange your burners and regulators to suit the gas that is furnished, demand of the company that it fulfil the law and the contract in regard to the quality of the gas, and give all gas-improving machines the go-by.3

"Light having, perhaps, been sufficiently considered for the present needs, we have now to note the effects of the combustion of gas upon the atmosphere, and through this upon the furnishing of rooms and the health of the persons living therein," said the chemist, again taking up his manuscript. "The usual products from the combustion of common illuminating gas are carbonic acid, sulphuric acid, ammonia and water-vapor. Every burner consuming five cubic feet of gas per hour spoils as much air as two full-grown men: it is therefore evident that the air of a room thus lighted would soon become vitiated if an ample supply of fresh air were not frequently admitted.

"Remember," said he, looking up from the paper, "that nearly the same effects proceed from the combustion of candles and lamps of every kind when a sufficient number of these are burned to give an equal amount of light. Carbonic acid is easily got rid of, for the rooms where gas is burned usually have sufficient ventilation near the floor by means of a register, or even the slight apertures under the doors—together with their frequent opening—to carry off the small quantity emitted by one or two burners. But there are other gases which must have vent at the upper part of the room, while fresh air should be admitted to supply the place of that which is chemically changed."

Returning to his manuscript, he continued: "The burners which give the least light, burning instead with a low, blue flame, form the most carbonic acid and free the most nitrogen. Such are all the burners for heat rather than light. But the formation of sulphuric acid gas may be the same in each. In the yellow flame the carbon particles escape to darken the light colors of the room, not being heated sufficiently to combine with the oxygen. This product of the combustion of gas (free carbon) might be regarded as rather wholesome than otherwise (as its nature is that of an absorbent) were it not the worst kind of dust to breathe—in fact, clogging the lungs to suffocation. In vapor gas—made at low heat—the carbon is in a large degree only mechanically mixed with the hydrogen, and is liable, especially in cold weather, to be deposited in the pipes. This leaves only a very poor, thin gas, mainly hydrogen, which burns with a pale blue flame, as seen in cold spells in winter. High heats and short charges in the retorts of the manufactory give a purer gas and a larger production. Gas made at high heat will reach the consumer in any weather very nearly as rich as when it leaves the gas-holder; for, thus made, the hydrogen and carbon are chemically combined, instead of the hydrogen merely bearing a quantity of carbon-vapor mechanically mixed and liable to deposit with every reduction of temperature. To relieve the atmosphere of the gases and vapors proceeding from combustion is, of course, the purpose of ventilation. The sulphuric acid gas and ammonia will be largely in combination with the water-vapor, which also proceeds from combustion, so that all will be got rid of together. The vaporization of libraries to counteract the excessive dryness (or drying, rather) which causes leather bindings to shrink and to break at the joints, would be of doubtful utility, since it might only serve to carry into the porous leather still more of the gases just mentioned. The action of both sulphuric acid and ammonia is, undoubtedly, to destroy the fibre of leather, so that it crumbles to meal or falls apart in flakes.

"In a very interesting paper read by Professor William R. Nichols of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology before the American Association of Science at its Saratoga meeting in 1879, the results of many analyses of leather bindings were given, showing the presence of the above-named substances in old bindings in many times greater quantity than in new. Still, their presence did not prove them to be the cause of the decay; and Professor Nichols proposes to ascertain the fact by experiments requiring some years for demonstration.

"In the hope of deciding the question with reasonable certainty at once, I have made careful examinations of the books in the three largest libraries of Boston and Cambridge, each differing from the others in age and atmosphere. The bindings of the volumes examined bore their own record in dates and ownership, by which the conditions of their atmosphere in respect to gas and (approximately) to heat were made known for periods varying from current time to over two hundred years. In the Public Library the combined influences of gas, heat and effluvium have wrought upon the leather until many covers were ready to drop to pieces at a touch. The binding showed no more shrinkage than in the other libraries, but in proportion to the time the books had been upon the shelves the decay of the leather was about the same as in the Athenæum. I am informed that many of the most decayed have from time to time been rebound, so that a full comparison cannot be made between this and the others. In the Athenæum less gas has been used, and there is very little effluvium, but the mealy texture of the leather is general among the older tenants of the shelves. Numbers of volumes in the galleries were losing their backs, which were more or less broken off at the joints from the shrinkage and brittleness of the leather. The plan has been proposed of introducing the vapor of water to counteract the effects of dryness upon the bindings. In this library the atmosphere has the usual humidity of that out of doors, being warmed by bringing the outer air in over pipes conveying hot water, while the other libraries have the higher heat of steam-pipes. If, therefore, its atmosphere differs from that of the other libraries in respect to moisture, the variation is in the direction of greater humidity, without any corresponding effect on the preservation of bindings. In fact, proper ventilation and low shelves seem to be the true remedies for these evils, or, rather, the best means of amelioration, since there is no complete antidote to the decay common to all material things. The last condition involves the disuse of galleries and of rooms upon more than one flat, unless the atmosphere in the upper portions of the lower rooms be shut off from the higher, as it should be. Another precaution which might be taken with advantage is to use the higher shelves for cloth bindings.

"In the Harvard College Library no gas has ever been used, nor any other artificial illuminator to much extent. Neither had any large number of the volumes been exposed to the products of gas-combustion, except for a brief time before they were placed here. The bindings in this library showed very little crumbling, but many covers were breaking at the joints from the shrinking which arises from excessive dryness. In common with many other substances, leather yields moisture to the air much more readily than it receives it from that medium. Cloth bindings showed no decay at all here—very little in any of the libraries, except in the loss of color. It should be stated that the volumes which I examined at Harvard College were generally older than those inspected in the other libraries. There are parchment bindings in each of the libraries hundreds of years old, apparently just as perfect in texture as when first placed upon the shelves of the original owner. The parchment was often worn through at the angles, but there was no breakage from shrinking, the material having been shrunken as much as possible when prepared from the skin. At Harvard College I examined an embossed calf binding stretched on wooden sides which was above a hundred years old. It was in almost perfect preservation, and not much shrunken. This volume, being very large, was on a shelf next the ground floor—a position which it had probably held ever since the erection of the building.

"Professor Nichols does not mention morocco in his tables of analyses. Indeed, morocco was so little used for bookbindings until within about thirty years that it affords a less ample field for investigation than any other of the leathers now in common use. My attention was therefore directed specially to this material, of which I found some specimens having a record of nearly fifty years. My observation was, that in all the libraries these were less affected by decay, in proportion to their age, than other leathers. In Harvard College Library the best Turkey morocco, with forty years of exposure, showed no injury except from chafing. The outer integument was often worn away, exposing the texture of the skin, which was still of strong fibre. In the Athenæum, on the contrary, many of the moroccos showed the same decay as the calf, russia and sheep. There was, however, a wide difference in the condition of moroccos of the same age—some showing as much decay as the calf, while others had scarcely any of the disintegration common to the older calf bindings. The same might, indeed, be said of all leathers, those tanned by the quick modern methods, with much more acid than is used in old processes, in which time is a large factor, showing always a more rapid deterioration. But, the methods being the same, morocco, the oiliest of the common leathers and the one having the firmest cuticle, endures the best.

"The order of endurance of leather (as observed by librarians) against atmospheric effects is as follows, descending from the first to the last in order: Parchment, light-colored morocco, sheep, russia, calf. Cloth wears out quickly by use, but appears—the linen especially—to be affected by the atmosphere only in loss of color. These observations all refer to the ordinary humidity of the air in frequented rooms.

"This, then, is the result of my inquiries: I found the shrinking and breaking resulting from heat much the same in all the libraries, but most in that where the heating is from the outer air brought in over hot-water pipes, the two other libraries examined being warmed by steam-pipes having a higher temperature. I found the mealy structure—or instead thereof flakiness—to prevail most in the Athenæum, next in the Public Library: in the latter, however, many volumes have been rebound, thus raising the average of condition. In the Harvard College Library no gas—in fact, little if any artificial light—is used, and here, too, the mealy structure and disintegration are mostly absent. I conclude, therefore, from these limited observations, that heat is responsible for a large part of the damage to leather bindings, its effects being evidently supplemented and hastened by gas-combustion.

"The ventilating lamps before described, though rather cumbrous to eyes accustomed to the small and simple apparatus commonly used, might prove valuable in rooms containing fabrics liable; to be injured by the gases from open burners."

As the chemist concluded his reading the traveller remarked to the somewhat weary listeners, "You now see the vast amount of study and care required to use gas with economy and safety. I could not have argued the cause of a new, clean, gasless and vaporless light like electricity any better myself."

"It will be found," responded the chemist, "that there are more troubles and dangers connected with the electric light—besides the larger expense—than are thought of now."

"That is so!" ejaculated the young fellow.

"At any rate," said the old gentleman, "gas stock won't go lower for twenty years than it has been this winter."

"You are all wedded to your idols," was the final protest of the traveller.

"I wish I was," murmured the young fellow, with a side-glance at his fair neighbor, who immediately removed to another part of the room.

GEORGE J. VARNEY.THE ΑΡΑΞ ΛΕΓΟΜΕΝΑ IN SHAKESPEARE

When we examine the vocabulary of Shakespeare, what first strikes us is its copiousness. His characters are countless, and each one speaks his own dialect. His little fishes never talk like whales, nor do his whales talk like little fishes. Those curious in such matters have detected in his works quotations from seven foreign tongues, and those from Latin alone amount to one hundred and thirty-two.

Our first impression, that the Shakespearian variety of words is multitudinous, is confirmed by statistics. Mrs. Cowden Clarke has counted those words one by one, and ascertained their sum to be not less than fifteen thousand. The total vocabulary of Milton's poetical remains is no more than eight thousand, and that of Homer, including the Hymns as well as both Iliad and Odyssey, is about nine thousand. In the English Bible the different words are reckoned by Mr. G.P. Marsh in his lectures on the English language at rather fewer than six thousand. Those in the Greek Testament I have learned by actual count to be not far from five thousand five hundred.

Some German writers on Greek grammar maintain that they could teach Plato and Demosthenes useful lessons concerning Greek moods and tenses, even as the ancient Athenians, according to the fable of Phædrus, contended that they understood squealing better than a pig. However this may be, any one of us to-day, thanks to the Concordance of Mrs. Clarke and the Lexicon of Alexander Schmidt, may know much in regard to Shakespeare's use of language which Shakespeare himself cannot have known. One particular as to which he must have been ignorant, while we may have knowledge, is concerning his employment of terms denominated απαξ λεγόμενα.

The phrase απαξ λεγόμενα—literally, once spoken—may be traced back, I think, to the Alexandrian grammarians, centuries before our era, who invented it to describe those words which they observed to occur once, and only once, in any author or literature. It is so convenient an expression for statistical commentators on the Bible, and on the classics as well, that they will not willingly let it die.

The list of απαξ λεγόμενα—that is, words used once and only once—in Shakespeare is surprisingly long. It embraces a greater multitude than any man can easily number. Nevertheless, I have counted those beginning with two letters. The result is that the απαξ λεγόμενα with initial a are 364, and those with initial m are 310. There is no reason, that I know of, to suppose the census with these initials to be proportionally larger than that with other letters. If it is not, then the words occurring only once in all Shakespeare cannot be less than five thousand, and they are probably a still greater legion.

The number I have culled from one hundred and forty-six pages of Schmidt is 674. At this rate the total on the fourteen hundred and nine pages of the entire Lexicon would foot up 6504. It is possible, then, that Shakespeare discarded, after once trying them, more different words than fill and enrich the whole English Bible. The old grammarians tell us that a certain part of speech was called supine, because it was very seldom needed, and therefore almost always lying on its back—i.e. in Latin, supinus. The supines of Shakespeare outnumber the employés of most authors.

The array of Shakespearian απαξ λεγόμενα appears still vaster if we compare it with expressions of the same nature in the Scriptures and in Homer. In the English Bible words with the initials a and m used once only are 132 to 674 with the same initials in Shakespeare. The scriptural once-onlys would be more than twice as many as we find them were they as frequent in proportion to their total vocabulary as his are.

The Homeric απαξ λεγόμενα with initial m are 78, but were they as numerous in proportion to Homer's whole world of words as Shakespeare's are, they would run up to 186; that is, to more than twice as many as their actual number.

In the Greek New Testament I have enumerated 63 απαξ λεγόμενα beginning with the letter m—a larger number than you would expect, for it is as large as that in both English Testaments beginning with that same letter, which is also exactly 63. It indicates a wider range of expression in the authors of the Greek original than in their English translators.

The 310 Shakespearian words with initial m used once only I have also compared with the whole verbal inventory of our language so far as it begins with that letter. They make up one-fifth almost of that entire stock, which musters in Webster only 1641 words. You will at once inquire, "What is the nature of these rejected Shakespearian vocables, which he seems to have viewed as milk that would bear no more than one skimming?"

The percentage of classical words among them is great—greater indeed than in the body of Shakespeare's writings. According to the analysis of Weisse, in an average hundred of Shakespearian words one-third are classical and two-thirds Saxon. But then all the classical elements have inherent meaning, while half of the Saxon have none. We may hence infer that of the significant words in Shakespeare one-half are of classical derivation. Now, of the απαξ λεγόμενα with initial a, I call 262 words out of 364 classical, and with initial m, 152 out of 310; that is, 414 out of 674, or about four-sevenths of the whole Shakespearian host beginning with those two letters. In doubtful cases I have considered those words only as classical the first etymology of which in Webster is from a classical or Romance root. In the biblical words used once only the classical portion is enormous—namely, not less than sixty-nine per cent.—while the classical percentage in Shakespearian words of the same class is no more than sixty-one.

Among the 674 a and m Shakespearian words occurring once only the proportion of words now obsolete is unexpectedly small. Of 310 such words with initial m, only one-sixth, or 51 at the utmost, are now disused, either in sense or even in form. Of this half-hundred a few are used in Shakespeare, but not at present, as verbs; thus, to maculate, to miracle, to mud, to mist, to mischief, to moral—also merchandized and musicked. Another class now wellnigh unknown are misproud, misdread, mappery, mansionry, marybuds, masterdom, mistership, mistressship.

Then there are slight variants from our modern orthography or meanings, as mained for maimed, markman for marksman, make for mate, makeless for mateless, mirable, mervaillous, mess for mass, manakin, minikin, meyny for many, momentarry for momentary, moraler, mountainer, misgraffing, misanthropos, mott for motto, to mutine, mi'nutely for every minute.

None seem wholly dead words except the following eighteen: To mammock, tear; mell, meddle; mose, mourn; micher, truant; mome, fool; mallecho, mischief; maund, basket; marcantant, merchant; mun, sound of wind; mure, wall; meacock, henpecked; mop, grin; militarist, soldier; murrion, affected with murrain; mammering, hesitating; mountant, raised up; mered, only; man-entered, grown up.

About one-tenth of the remaining απαξ λεγόμενα with initial m are descriptive compounds. Among them are the following adjectives: Maiden-tongued, maiden-widowed, man-entered (before noted as obsolete), many-headed, marble-breasted, marble-constant, marble-hearted, marrow-eating, mean-apparelled, merchant-marring, mercy-lacking, mirth-moving, moving-delicate, mock-water, more-having, mortal-breathing, mortal-living, mortal-staring, motley-minded, mouse-eaten, moss-grown, mouth-filling, mouth-made, muddy-mettled, momentary-swift, maid-pale. From this list, which is nearly complete, it is evident that such compounds as may be multiplied at will form but a small fraction of the words that are used once only by Shakespeare.

The words used once only by Shakespeare are often so beautiful and poetical that we wonder how they could fail to be his favorites again and again. They are jewels that might hang twenty years before our eyes, yet never lose their lustre. Why were they never shown but once? They remind me of the exquisite crystal bowl from which I saw a Jewess and her bridegroom drink in Prague, and which was then dashed in pieces on the floor of the synagogue, or of the Chigi porcelain painted by Raphael, which as soon as it had been once removed from the Farnesina table was thrown into the Tiber. To what purpose was this waste? Why should they be used up with once using? Specimens of this sort, which all poets but Shakespeare would have paraded as pets many a time, are multifarious. Among a hundred others never used but once, we have magical, mirthful, mightful, mirth-moving, moonbeams, moss-grown, mundane, motto, matin, mural, multipotent, mourningly, majestically, marbled, martyred, mellifluous, mountainous, meander, magnificence, magnanimity, mockable, merriness, masterdom, masterpiece, monarchize, menaces, marrowless.

Again, a majority of Shakespearian απαξ λεγόμενα being familiar to us as household words, it seems impossible that he who had tried them once should have need of them no more. Instances—all with initial m—are as follows: mechanics, machine, maxim, mission, mode, monastic, marsh, magnify, malcontent, majority, manly, malleable, malignancy, maritime, manna, manslaughter, masterly, market-day-folks, maid-price, mealy, meekly, mercifully, merchant-like, memorial, mercenary, mention, memorandums, mercurial, metropolis, miserably, mindful, meridian, medal, metaphysics, ministration, mimic, misapply, misgovernment, misquote, misconstruction, monstrously, monster-like, monstrosity, mutable, moneyed, monopoly, mortise, mortised, muniments, to moderate, and mother-wit These words, and five thousand more equally excellent, which have remained part of the language of the English-speaking world for three centuries since Shakespeare, and will no doubt continue to belong to it for ever, we are apt to declare he should have worn in their newest gloss, not cast aside so soon. Why was he as shy of repeating any one of them even once as Hudibras was of showing his wit?—