Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 407, September, 1849

"In our new and neglected communities, Chartism is found in its worst manifestations – not as an adhesion to political dogmas, but as an indication of that class-antagonism which proclaims the rejection of our common Christianity, by denying the brotherhood of Christians. This antagonism originated, as great social evils ever do, in the neglect of duty by the master, or ruling class. They first practically denied the obligation imposed on every man who undertakes to govern or to guide others, whether as master or ruler, to care for, to counsel, to instruct, and, when necessary, to control those who have contracted with him the dependent relation of servant or subject; and from that neglect of duty has sprung up, and been nourished in the subject, or dependent class, impatience of restraint, discontent with their condition, a jealousy, often amounting to hatred, of the classes above them, and a desire, first to destroy to the base, and then to reconstruct on different principles, the political and social systems under which they live. Thus will it ever be, as thus it ever has been, throughout the world's history; and the violation or neglect of duty, whether by nations or individuals, in its own direct and immediate consequences, works out the appropriate national or individual punishment; and those who sow the wind, will surely reap the whirlwind – it may be, not in their own persons, but in the visitation of their children's children."

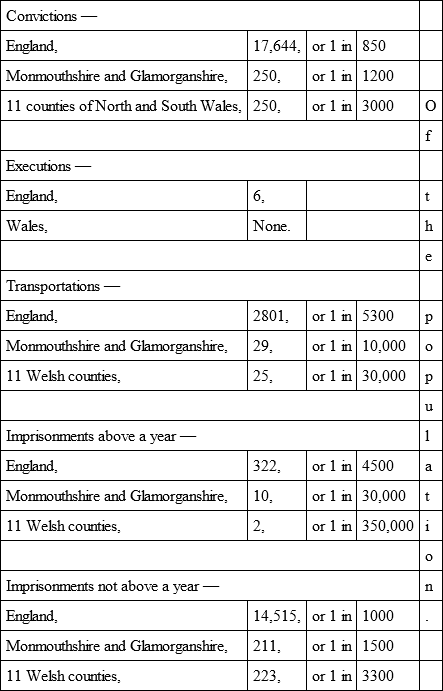

Notwithstanding the lamentable prevalence of diseased political and moral feeling among a certain portion of the inhabitants of South Wales, it is certain that the primitive simplicity of character by which the Welsh nation is still distinguished, tends in a great degree to keep them from the commission of those crimes which attract the serious notice of the law. In most of the counties of Wales, the business on the crown side at the assizes is generally light, sometimes only nominal; and the general condition of the public mind may be fairly judged of from the following table of criminal returns for 1846: —

"The comparative rarity of crime in the eleven Welsh counties is represented by 1 offence to 3000 of the population; and the absence of serious crimes by the small number of transportations, namely, 25, or 1 in 30,000; and still more remarkably, by the large proportion of the offenders whose punishment did not exceed a year's imprisonment, namely, 223 out of 250, leaving 27 as the number of all the criminals convicted in a year, in eleven counties, whose punishment exceeded a year's imprisonment."

The accusation that was brought forward in the unfortunate Blue Books against the chastity of the Welsh women, and which was the real cause of the hubbub made about them, we dismiss from our consideration. It arose from a misapprehension of the degree of criminality implied by the prevalence of an ancient custom, which exists not in Wales only, but we rather think amongst the peasants of the whole of Europe, and certainly as widely in England as in Wales. Whether existing in other nations or not, the Welsh press, (generally conducted by Englishmen, be it observed,) and the pseudo-patriots of Wales, a noisy empty-headed class, made a great stir about it, and declaimed violently: they did not, however, adduce a single solid argument in disproof of the accusation. There is one fact alone which is quite sufficient to explain the accusation and to remove the stain: bastardy is not less common than in England, but prostitution is almost unknown; the common people do not consider that to be a crime before marriage, which after it they look upon as a heinous enormity. Such is their code of national morals: whether right or wrong, they abide by it pretty consistently; and they appear to have done so from time immemorial. They mean no harm by it, and they look upon it as venial: this is the state of the national feeling, and it settles the question.

We now turn to the chapters that refer to the religious condition of the country, which is treated of by the author at full length, though our own comments must be necessarily brief. He gives a luminous account of the rise and progress of modern dissent in Wales; from which, however, we give the highly improbable statement, that the actual number of members of dissenting congregations, of all denominations in Wales, amounted to only 166,606 in 1846, with 1890 ministers. We should rather say that, whatever the gross population of the country may be at the present moment, there is not more than one person out of ten, who have arrived at years of discretion, belonging altogether to the church; and we infer the fulness of dissenting chapels, not only from the crowds that we have seen thronging them, on all occasions, but also from the thinness of the congregations at church. For the Welsh are eminently an enthusiastic, and we might almost say, a religious people: they are decidedly a congregational people; and as for staying at home on days of public worship, no such idea ever yet entered a true Welshman's head. We think that the author must have been misinformed on this head, and that the numbers should rather be the other way – 100,000 out of 900,000 being a very fair proportion for the members of the church.

For all this there are good and legitimate reasons to be found, not only in what is adduced in this work on the church establishment, but also in the current experience of every man of common observation throughout the Principality. The wonder is, not that dissent should have attained its present height, but that the church should have continued to exist at all, amidst so many abuses, so much ignorance, so much neglect, and such extraordinary apathy – until of late days – on the part of her rulers. The actual condition of the church in Wales may be summed up in a few words – it is that of the church in Ireland: only those who differ from it are Protestants instead of Roman Catholics. Let us quote Sir Thomas Phillips again: —

"We have now passed in review various influences by which the church in Wales has been weakened. We have seen the religious edifices erected by the piety of other times, and with the sustentation of which the lands of the country have been charged, greatly neglected, whilst the lay officers, on whom the duty of maintaining those buildings in decent condition was imposed, are sometimes not appointed, or, if appointed, make light or naught of their duties: we have seen ecclesiastical officers, specially charged with the oversight of the churches, not required to exercise functions which have been revived by recent legislative enactments: we have found a clergy, with scanty incomes, and a want of decent residences, ministering in a peculiar language, with which the gentry have most commonly an imperfect and often no acquaintance – even where it is the language of public worship – influences which lower the moral and intellectual standard of the clergy, by introducing into holy orders too large a proportion of men, whose early occupations, habits, and feelings, do not ordinarily conduce to maintain the highest standard of conduct, and who (instead of forming, as in England, a minority of the whole body, and being elevated in tone, morally and mentally, by association with minds of higher culture) compose the large majority of the clergy of the Principality. It cannot, then, be matter of surprise, if amongst those men some should be found who (not being received on a footing of equality into the houses of the gentry, over whom they exercise but little influence) again resume the habits from which they were temporarily rescued by an education itself imperfect, and, selecting for daily companionship uneducated men, are either driven for social converse to the village alehouse, or become familiarised with ideas and practices unsuited to the character, injurious to the position, and destructive to the influence of the Christian pastor. Nor could we wonder, if even the religious opinions and well-meant activity of the more zealous among persons thus circumstanced, were to borrow their tone and colour from the more popular influences by which they are surrounded, rather than from the profounder and more disciplined theology of the church of which they are ministers. We have found the ecclesiastical rulers of this clergy and chief pastors of the people, as well as many other holders of valuable church preferment, to consist often of strangers to the country, ignorant alike of the language and character of the inhabitants, by many of whom they are regarded with distrust and dislike; unable to instruct the flock committed to their charge, or to teach and exhort with wholesome doctrine, or to preach the word, or to withstand and convince gainsayers, in the language familiar to the common people of the land. Finally, we have seen the church, whilst she compassed sea and land to gain one proselyte from the heathendom without, allow a more deplorable heathendom to spring into life within her own borders; and the term baptised heathens, instead of being a contradiction in terms, has become the true appellation of thousands of men and women in this island of Christian profession and Christian action. Nevertheless the Welsh are not an irreligious people; and whilst the religious fabrics of dissent are reared up by the poor dwellers of their mountain valleys, in every corner in which a few Christian men are congregated, and these buildings are thronged by earnest-minded worshippers, assembled for religious services in the only places, it may be, there dedicated to God's glory, the feeling must be ever present, 'Surely these men and women might have been kept within the fold of the church.' A supposed excitability in the Cambro-Briton, a love for extemporaneous worship, and an impatience of formal services, have been represented as intractable elements in the character of this people. Even if such elements exist, it does not follow that they might not have received a wholesome direction; while, unfortunately, their action now finds excuse in the neglect and provocation which alone render them dangerous. The church in Wales has been presented in her least engaging aspect; her offices have been reduced to the baldest and lowest standard; and whilst no sufficient efforts have been employed to make the beauty of our liturgical services appreciated by the people, neither has any general attempt been made to enlist, in the performance of public worship, their profound and characteristic enjoyment of psalmody, by accustoming them to chant or sing the hymns of the church."

All the abuses of ecclesiastical property seem to have flourished in the land of Wales, as in a nook where there was no chance of their being ever brought to light; – more than one-half of the income of the church, for parochial purposes, totally alienated; the bishops and other dignitaries totally asleep, and exercising no spiritual supervision; pluralities and non-residence prevailing to a great extent; the character of the clergy degraded; the gentry and aristocracy of the land starving the church, and giving it a formal, not a real support; – how can any spiritual system flourish under such an accumulation of evils? The true spirit of the church being dead, a reaction on the part of the people inevitably took place; and it is hardly going too far to say, that had it not been for the efforts of dissenters, "progressing by antagonism," Christianity would by this time have fallen into desuetude within the Principality.

It is a very thorny subject to touch upon, in the present excitable state of the world, and therefore we refrain; but we would earnestly solicit the attention of our readers to the pages of Sir Thomas Phillips, – himself one of the very few orthodox churchmen still left in Wales, – for a proof of what we have asserted; and should they still doubt, let them try an excursion among the wilds of the northern, or the vales of the southern division of the country, and they will become full converts to our opinion. Things, however, in this respect are mending – the church has at length stirred, abuses are becoming corrected, the ecclesiastical commissioners have done justice in several cases – and in none more signally than in the extraordinary epitome of all possible abuses, shown by the chapter of Brecon – abuses existing long before the Reformation, but increased, like many others, tenfold since that period. The church has never yet had fair play in the country, for she has never yet done herself —much less her people– justice; so that what she is capable of effecting among the Cambrian mountains cannot yet be predicated. We fondly think, at times, that all these evils might be abolished; but this is not the place for such a lengthy topic: we have adverted to the state of things as they have hitherto existed in the Principality, chiefly with the view of showing their influence upon the peculiar political and ethnical condition of the people, which it is our main object to discuss. We will content ourselves with observing, that Sir Thomas Phillips' remarks on this subject, and on the connexion of the state with the education of the country, are characterised by sound religious feeling, and a true conservative interpretation of the political condition of the empire.

On a calm view of the general condition of Wales, we are of opinion that the inhabitants, the mass of the nation, are as well off, in proportion to the means of the country itself, to the moderate quantity of capital collected in the Principality, and the number of resident gentry – which is not very great – as might have been fairly expected; and that it is no true argument against the national capabilities of the Welsh, that they are not more nearly on a level with the inhabitants of some parts of England. The Welsh inhabit a peculiar land, where fog and rain, and snow and wind, are more prevalent than fine working weather in more favoured spots of this island. A considerable part of their land is still unreclaimed and uncultivated – their country does not serve as a place of passage for foreigners. Visitors, indeed, come among them; but, with the exception of the annual flocks of summer tourists, and the passengers for Ireland on the northern line of railroad, they are left to themselves without much foreign admixture during a great portion of each year. The mass of the gentry are neither rich nor generous: there are some large and liberal proprietors, but the body of the gentry do not exert themselves as much as might be expected for the benefit of their dependants; and hence the Welsh agriculturist lacks both example and encouragement. That the cultivation of the land, therefore, should be somewhat in arrear, that the mineral riches of the country should be but partially taken advantage of, and that extensive manufactures should rarely exist amongst the Welsh, ought not to form any just causes of surprise: these things will in course of time be remedied of themselves. The main evil that the Welsh have to contend against is one that belongs to their blood as a Celtic nation; and which, while that blood remains as much unmixed as at present, there is no chance of eradicating. We allude to that which has distinguished all Celtic tribes wherever found, and at whatever period of their history – we mean their national indolence and want of perseverance – the absence of that indomitable energy and spirit of improvement which has raised the Anglo-Saxon race, crossed as it has been with so many other tribes, to such a mighty position in the dominion of the world.

This absence of energy is evident upon the very face of things, and lies at the bottom of whatever slowness of improvement is complained of in Wales. It is the same pest that infests Ireland, only it exists in a minor degree; it is that which did so much harm to the Scottish Highlands at one period of their history; and it is a component cause of many anomalies in the French character, though in this case it is nearly bred out. One of the most striking evidences and effects of it is the dirt and untidiness which is so striking and offensive a peculiarity of Welsh villages and towns – that shabby, neglected state of the houses, streets, and gardens, which forms such a painful contrast the moment you step across the border into the Principality. In this the Welsh do not go to the extremes of the Irish: they are preserved from that depth of degradation by some other and better points of their character; but they approach very closely to the want of cleanliness observable in France – and the look of a Welsh and a French village, nay, the very smell of the two places, is nearly identical. A Welsh peasant, amidst his own mountains, if he can get a shilling a-day, will prefer starving upon that to labouring for another twelvepence. A farmer with £50 a-year rent has no ambition to become one of £200; the shopkeeper goes on in the small-ware line all his life, and dies a pedlar rather than a tradesman. There are brilliant and extraordinary exceptions to all this, we are well aware; nay, there are differences in this respect between the various counties, – and generally the southern parts of Wales are as much in advance of the northern, in point of industry, as they are in point of intellect and agricultural wealth. It is the general characteristic of this nation – and it evidences itself, sometimes most disagreeably, in the want of punctuality, and too often of straightforward dealing, which all who have any commercial or industrial communications – with the lower and middle classes of the Welsh have inevitably experienced. It is the vice of all Celtic nations, and is not to be eradicated except by a cross in the blood. Joined with all this, there is a mean and petty spirit of deceit and concealment too often shown even in the middle classes; and there is also the old Celtic vice of feud and clanship, which tends to divide the nation, and to impede its advancement in civilisation. Thus the old feud between North and South Wales still subsists, rife as ever; the northern man, prejudiced, ignorant, and indolent, comes forth from his mountains and looks down with contempt on the dweller in the southern vales, his superior in all the arts and pursuits of civilised life. Even a difference of colloquial dialects causes a national enmity; and the rough Cymro of Gwynedd still derides the softer man from Gwent and Morganwg. All these minor vices and follies tend to impair the national character – and they are evidences of a spirit which requires alteration, if the condition of the people is to be permanently elevated. On the other hand, the Welsh have many excellent qualifications which tend to counteract their innate weaknesses, and afford promise of much future good: their intellectual acuteness, their natural kindliness of heart, their constitutional poetry and religious enthusiasm, their indomitable love of country – which they share with all mountain tribes – all these good qualities form a counterbalance to their failings, and tend to rectify their national course. Take a Welshman out of Wales, place him in London or Liverpool, send him to the East Indies or to North America, and he becomes a banker of fabulous wealth, a merchant of illimitable resources, a great captain of his country's hosts, or an eminent traveller and philosopher; but leave him in his native valley, and he walks about with his hands in his pockets, angles for trout, and goes to chapel with hopeless pertinacity. Such was the Highlander once; but his shrewd good sense has got the better of his indolence, and he has come out of his fastnesses, conquering and to conquer. Not such, but far, far worse is the Irishman; and such will he be till he loses his national existence. St Andrew is a better saint than St David, and St David than St Patrick; but they all had the same faults once, and it is only by external circumstances that any amelioration has been produced.

It is a fact of ethnology, that while a tribe of men, kept to itself and free from foreign admixture, preserves its natural good qualities in undiminished excellence through numerous ages, all its natural vices become increased in intensity and vitality by the same circumstances of isolation. Look at the miserable Irish, always standing in their own light; look at the Spaniards, keeping to themselves, and stifling all their noble qualities by the permanence of their national vices; look at the tribes of Asia, doomed to perpetual subjection while they remain unmixed in blood. Had the Saxons remained with uncrossed blood, they had still been stolid, heavy, dreaming, impracticable Germans, though they had peopled the plains of England; but, when mixed with the Celts and the Danes, they formed the Lowland Scots, the most industrious and canniest chields in the wide world: fused with the Dane and Norman, and subsequently mixed with all people, they became Englishmen —rerum Domini– like the Romans of old. It may be mortifying enough to national pride, but the fact is, nevertheless, patent and certain, that extensive admixture of blood commonly benefits a nation more than all its geographical advantages.

It is our intimate conviction of the truth of this fact, so clearly deducible from the page of universal history, and especially from the border history of England and Wales, that shows us, inter alia, how false and absurd is the pretended patriotism of a small party among the gentry and clergy of Wales who have lately raised the cry of "Wales for the Welsh!" and who would, if they could, get up a sort of agitation for a repeal of the Norman conquest! There are sundry persons in Wales who, principally for local and party purposes, are trying to keep the Welsh still more distinct from the English than they now are, – who try to revive the old animosities between Celt and Saxon, – who pretend that Englishmen have no right even to settle in Wales, – and who, instead of promoting a knowledge of the English language, declaim in favour of the exclusive maintenance of the Welsh. These persons, actuated by a desire to bring themselves forward into temporary notoriety, profess, at the same time, by an extraordinary contradiction, to be of the high Conservative party, and amuse themselves by thwarting the Whigs, and abusing the Dissenters, to the utmost of their power. They are mainly supported – not by the Welsh of the middle classes, who have their separate hobby to ride, and who distrust the former too much to co-operate with them – but by English settlers in Wales, and on its borders, who, in order to make for themselves an interest in the country, pander to the prejudices of a few ambitious twaddlers, and get up public meetings, at which more nonsense is talked than any people can be supposed gullible enough to swallow. This spirit exists in the extreme northern portion of Wales, in Flintshire, Denbighshire, and Caernarvonshire; and on the south-eastern border of the country, in Monmouthshire, more than in any other district. It is doomed to be transient, because it is opposed, not less to the wishes and the good sense of the mass of the people, than to the views and policy of the nobles and leading gentry of the Principality. One or two radical M.P.s, a few disappointed clergymen, who fancy that their chance of preferment lies in abusing England, and a few amateur students of Welsh literature, who think that they shall thereby rise to literary eminence, constitute the clique, which will talk and strut for its day, and then die away into its primitive insignificance. But, by the side of this unimportant faction, there does exist, amongst the working classes and the lower portion of the middle orders, a spirit of radicalism, chartism, or republicanism, – for they are in reality synonymous terms, – which is doing much damage to the Principality, and which it lies easily within the power of the upper classes to extinguish, – not by force, but by kindness and by example.

It has been one of the consequence of dissent in Wales – not intended, we believe, by the majority of the ministers, but following inevitably from the organisation of their congregations, – that a democratic spirit of self-government should have arisen among the people, and have interwoven itself with their habits of thought and their associations of daily life. The middle and lower classes, separated from the upper by a difference of language, and alienated from the church by its inefficiency and neglect, have thrown themselves into the system of dissent, – that is, of self-adopted religious opinions, meditated upon, sustained, and expounded in their own native tongue, with all the enthusiasm that marks the Celtic character. The gulf between the nobles and gentry of Wales on the one side, and the middle and lower classes on the other, was already sufficiently wide, without any new principle of disunion being introduced; but now the church has become emphatically the church of the upper classes alone, – the chapel is the chapel of the lower orders – and the country is divided thereby into two hostile and bitterly opposed parties. On the one hand are all the aristocratic and hierarchic traditions of the nation; on the other is the democratic self-governing spirit, opposed to the former as much as light is to darkness, and adopted with the greater readiness, because it is linked to the religious feelings and practices of the vast majority of the whole people. Dissent and democratic opinions have now become the traditions of the lower orders in Wales; and every thing that belongs to the church or the higher orders of the country, is repulsive to the feelings of the people, because they hold them identical with oppression and superstition. The traditions of the conquest were quite strong enough, – the Welshman hated the Englishman thoroughly enough already; but now that he finds his superiors all speaking the English tongue, all members of the English church, he clings the more fondly and more obstinately to his own self-formed, self-chosen, system of worship and government, and the work of reunion and reconciliation is made almost impossible. In the midst of all this, the church in Wales is itself divided into high and low, into genteel and vulgar; the dignitaries hold to the abuses of the system, – and some, less burdened with common sense than the rest, gabble about "Wales and the Welsh," as if any fresh fuel were wanted to feed the fire already burning beneath the surface of society!