Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 407, September, 1849

Our readers will very likely remember that certain Reports on the state of education in Wales, printed by order of the House of Commons, gave immense offence to all who had got ever so little Welsh blood in their veins. We reviewed these very reports, and gave our opinions on Welsh education at considerable length; and therefore we do not open Sir Thomas Phillips' pages with the intention of reverting to that part of the subject, though the author, in compiling it, seems to have had the education of his countrymen principally in view.

We consider, however, that a work written by a gentleman, known for his forensic abilities and literary pursuits, upon a large portion of this island, and purporting to be a complete account of its moral and social condition, must form a suitable topic for review and discussion. Our readers will not repent our introducing it to their notice: we can at once assure them that it will amply repay the trouble – if it be a trouble at all – of perusing it. The style is graceful and yet nervous; the whole tone and colour of the thoughts of the author show the gentleman; while the general compilation and discussion of the facts collected prove Sir Thomas Phillips to have the mind and the abilities of a statesman.15 Another, and a more important reason, however, why this work will be acceptable to many of our readers, is that it touches upon various questions which, at times like the present, are of vital importance to the welfare, not of Wales only, but of the British empire; and that it proves the existence of feelings in the Principality – mentioned by us on a previous occasion – which ought to be brought before the notice of the public, and commented upon. This is the task which we reserve for ourselves after reviewing more in detail the work of the learned author; for Wales may become a second Ireland in time, if neglected, or it may continue to be a source of permanent strength to the crown, if properly treated and protected. The existence of such a state of things is hinted at in the preface – an uncommonly good one, by the way, and dated, with thorough Cambrian spirit, on St David's Day, if not from the top of Snowdon, yet from the more prosaic and less mountainous locality of the Inner Temple. The author's words are —

"Amongst the mischievous results which the temper and spirit of the reports have provoked in Wales, I regard with discomfort and anxiety a spirit of isolation from England, to which sectarian agencies, actively working through various channels, have largely ministered. In ordinary times this result might be disregarded; but at a period of the world's history when the process of decomposition is active amongst nations, and phrases which appeal to the sympathies of race become readily mischievous, it behoves those very excellent persons, who claim Wales for the Welsh, to consider whether they are prepared to give up England to the English, and to relinquish the advantages which a poor province enjoys by its union with a rich kingdom. For generations, Welshmen have been admitted to an equal rivalry with Englishmen, as well in England as in those colonial possessions of the British crown, which have offered so wide a field for enterprise, and secured such ample rewards to provident industry; and, whether at the bar or in the senate, or in the more stirring feats of war, they have obtained a fair field, and have won honourable distinction. There are offices in the Principality, the duties of which demand a knowledge of the Welsh language, and for them such knowledge should be made a condition of eligibility, in the same manner as a knowledge of English would be required, under analogous circumstances, in England. In the law these offices will be few, and probably confined to the local judges; as it will not be seriously proposed that, in our assize courts, the pleadings of the advocate, and the address of the judge, shall be delivered in the Welsh language; and even in the courts of quarter-sessions, which are composed of local magistrates most of whom were born and reside in the country, but few of those gentlemen could address a jury in their own tongue. A remedy for the inconvenience occasioned by an ignorant or imperfect acquaintance, on the part of the people, with the language employed in courts of justice, must be looked for in that instruction in the English language which is intended to be provided for all, and which is necessary to qualify men to appear as witnesses, or to serve as jurors, in courts wherein the proceedings are conducted in that tongue. The difficulties arising from language are principally felt in the Church: and it seems a truism to affirm, that where Welsh is the ordinary language of public worship, and the common medium of conversation, the language should be known to those who are to teach and exhort the people, and to withstand and convince gainsayers. The nomination of foreign prelates to English sees before the Reformation, occasioned great dissatisfaction in the minds of the English clergy, and tended to alienate them from the papacy; and yet men who are prompt to recognise that grievance, are insensible to the effect produced on the Welsh clergy, by their general exclusion from the higher offices of the Church. The ignorance of Welsh in men promoted to bishoprics in Wales, may be more than compensated for by the possession of other qualifications; and a rigid exclusion from the episcopal office in the Principality of every man who is unacquainted with the language of the people, might be inconvenient, if not injurious, to the best interests of the Church. The selection, however, for the episcopal office of men conversant with the language of the country, when otherwise qualified to bear rule in the Christian ministry, would give a living reality to the episcopate in the Principality, and might materially aid in bringing back the people into the fold of the Church."

The difference of language is here made the principal grievance between the Saxon and Celtic population; and it is certainly one of the principal, though not the main, nor the only, cause of the unpleasantness and unsettledness of feeling that exists in Wales towards England and English people. Where two languages exist, it is impossible but that national distinctions should exist also; and as the traditions of conquest, and the hereditary consciousness of political inferiority, are some of the last sentiments that abandon a vanquished people, so it is probable that the Welsh will remain a distinct people for more centuries to come than we care to count up. We do not know but that, to a certain extent, it may be a source of strength to England that it should be so, though it will undoubtedly be a cause of weakness and division to Wales. Nevertheless, the difficulty is not so great as may be at first sight supposed. In adverting to this part of the subject, Sir Thomas Phillips observes —

"When Edward the First conquered the country, and subjected the natives to English rule, he was deeply sensible of the difficulty which now paralyses education commissioners, and he dealt with it in a manner characteristic of the monarch and the times. Of him Carlyle would say, he was a real man, and no sham; and did not believe in any distracted jargon of universal rose-water in this world still so full of sin. Accordingly, he gathered all the Welsh bards together, and put them to death; and Hume, a philosophic and ordinarily not a cruel historian, says this policy was not absurd. English legislation, between the conquest of the country by Edward the First and its incorporation with England by Henry the Eighth, was characterised by a deliberate and pertinacious endeavour to extirpate the language and subjugate the spirit of the inhabitants. By laws of the Lancastrian princes, (whose usurpation was long resisted by the Welsh people,) 'rhymers, minstrels, and other Welsh vagabonds,' were forbidden to burden the country; the natives were not permitted to have any house of defence, to bear arms, or to exercise any authority; and an Englishman, by the act of marrying a Welsh woman, became ineligible to hold office in his adopted country. By statutes of Henry the Eighth, it was enacted, that law proceedings should be in the English tongue; that all oaths, affidavits, and verdicts, should be given and made in English; and that no Welsh person, 'who did not use the English speech' should hold office within the King's dominions. Even at the Reformation, which secured the sacred volume to Englishmen 'in their own tongue wherein they were born,' the revelation to man of God's will was not given to Welshmen in a language understood by the people. In 1562, however, provision was made for translating the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer into the British or Welsh tongue, by an act which declared that the most and greatest part of the Queen's loving subjects in Wales did not understand the English tongue, and therefore were utterly destitute of God's holy Word, and did remain in the like, or rather more, darkness and ignorance than they were in the time of papistry, and required that not only a Welsh, but also an English, Bible and Book of Common Prayer should be laid in every church throughout Wales, there to remain, that such as understood them might read and peruse the same; and that such as understood them not might, by conferring both tongues together, the sooner attain to the knowledge of the English tongue.

"Nearly six centuries have elapsed since the first Edward crossed the lofty mountains of North Wales, which, before him, no King of England had trodden, and in the citadel of Caernarvon received the submission of the Welsh people; and more than three centuries have passed away since the country was incorporated with, and made part of, the realm of England; and although, for so long a period, English laws have been enforced, and the use of the Welsh language discouraged, yet, when the question is now asked, what progress has been made in introducing the English language? the answer maybe given from Part II. of the Reports of the Education Commissioners, page 68. In Cardiganshire, 3000 people out of 68,766 speak English.16 The result may be yet more strikingly shown by saying that double the number of persons now speak Welsh who spoke that language in the reign of Elizabeth."

It is a mistaken idea to suppose that the Welsh language is hard to be acquired, – the very reverse of this is the fact,: there is probably no spoken language of Europe, not derived from the Latin, which may be so soon or so agreeably acquired as the Welsh. A good knowledge of it, so as to enable the learner to read and write it currently, may be attained certainly within a year by even a moderately diligent student; and the power of conversing in it with ease and fluency is to be gained within the course of perhaps a couple of years. The language is daily studied more and more by persons not connected with the Principality, and acquired by them; nay, what is a remarkable fact, next to the galaxy of the Williamses,17 the best Welsh scholar of the present day is Dr Meyer, the learned German librarian at Buckingham Palace; while Dr Thirlwall, the present bishop of St David's, has made himself, with only a few years' study, as good a Welsh scholar as he had long before been a German one. We believe that, if the present system of education be steadily carried out, with its consequent developments, in the Principality, the two languages, English and Welsh, will become equally familiar to those who may be born in the second generation from the present day; and that the inhabitants of Wales, becoming thoroughly bilingual– for we do not anticipate that they will abandon their ancient tongue – this apparent obstacle to a more complete amalgamation of interests between the two races will be entirely removed. One thing is certain, that the aptitude of Welsh children to learn English, of the purest dialectic kind, is very remarkable – and that the desire to acquire English is prevalent amongst all the people.

We confess that we should be sorry to see any language impaired, much less forgotten: they constitute some of the great marks which the Almighty has impressed upon the various tribes of his children – not lightly to be neglected nor set aside. They form some of the surest grounds of national strength and permanence; and they are some of those old and venerable things which, as true conservatives, we are by no means desirous to see obliterated or injured. As, however, it is obviously impossible that the whole literature of the Anglo-Saxon race should be translated into Welsh, it is essential to the Cambrians that they should no longer hesitate as to qualifying themselves for reading, in its own tongue, that literature which is exercising so great an influence over a large portion of the globe; and the possession of the two languages will tend to elevate the character, as well as to remove the prejudices, of the people that shall take the trouble to acquire them.

The social condition of Wales is gone into by the author at some length; but he confines his observations principally to the manufacturing and mining population of Glamorgan and the southern counties. Upon this part of the subject he has compiled much valuable information which, though not exactly new, tells well in his work when brought into a focus and reasoned upon. He introduces the subject thus: —

"The social condition of the inhabitants is influenced by the configuration of the country, for the most part abrupt, and broken into hill and valley; the elevation of the upper mountain ranges, which are the loftiest in South Britain, and the large proportion of waste and barren land; the humidity of the climate; the variety and extent of the mineral riches in certain localities; and the great length of the sea-coast, forming numerous bays and havens; and thus there is presented much variety in the occupation, and remarkable contrasts in the means of subsistence and habits of life, of the people. Monmouthshire, Glamorganshire, and the southern extremity of Breconshire, are the seat of the iron and coal trades. In the western part of Glamorganshire, around Swansea, and in the south-eastern corner of Carmarthenshire, copper ore, imported from Cornwall, as well as from foreign countries, is smelted in large quantities; and the same neighbourhood is the seat of potteries, at which an inexpensive description of earthenware is made. Coal, in limited quantities, and of a particular description, is exported from Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire; and lead ore and quarries of slate are worked in Cardiganshire. In North Wales, considerable masses of people are collected around the copper mines of Anglesey; amidst the slate quarries opened in the lofty mountains of Caernarvonshire and Merionethshire, as well as in some of the sea-ports of those counties; amongst the lead mines of Flintshire, and the coal and iron districts, which extend from the confines of Cheshire, through Flintshire and Denbighshire, to the confines of Merionethshire; and in those parts of Montgomeryshire, on the banks of the Severn, where flannel-weaving prevails. Formerly, the woollen cloths and flannels with which the people clothed themselves were manufactured throughout the country, at small mills or factories placed on the margin of mountain streams, which furnished the power or agency necessary for carrying on the process; but the growth of the large manufacturing establishments in the north of England and Scotland, and the substitution of cotton for wool in various articles of clothing, have uprooted many of the native factories, and reduced to very small dimensions the once important manufacture of homemade cloths and flannels. The larger portion of the industrial population of North Wales, and of the counties of Cardigan, Carmarthen, Radnor, and Pembroke, in South Wales, is engaged in agriculture. It consists, for the most part, of small farmers – a frugal and cautious race of men, employing but few labourers, and cultivating, by means of their own families and a few domestic servants, the lands on which they live.

"In times of mining and manufacturing prosperity, the productions of the agricultural and pastoral districts find ready purchasers, at remunerating prices, at the mining and manufacturing establishments, to which they are conveyed from distant places; and the surplus labour of the agricultural districts finds profitable employment at the mines, factories, and shipping ports, where a heterogeneous population is collected from every part of the kingdom. The wages of labour are, nevertheless, very low, in the agricultural portions both of North and South Wales; and are probably lower in the western counties of South Wales, and in some districts of North Wales, than in any other part of South Britain. The Welsh farmer presents, however, a stronger contrast than even the Welsh labourer to the same class in England. He occupies a small farm, employs an inconsiderable amount of capital, and is but little removed, either in his mode of life, his laborious occupation, his dwelling, or his habits, from the day-labourers by whom he is surrounded; feeding on brown bread, often made of barley, and partaking but seldom of animal food. The agricultural and pastoral population is, for the most part, scattered in lone dwellings, or found in small hamlets, in passes amongst the hills, on the sides of lofty mountains, or the margin of a rugged sea-coast, or on lofty moors, or table-land; and oftentimes this population can be approached only along sheep-tracks or bridle-paths, by which these mountain solitudes are traversed.

"Whilst, however, such is the condition of a wide area of the Principality, there is found in particular districts, of which mention has been already made, a population congregated together in large numbers, which has grown with a rapidity of which there is scarcely another example – not by the gradual increase of births over deaths, but by immigration from other districts, as well of Wales and England, as of Ireland and Scotland also. That immigration is not constant in its operation and regular in its amount, but fluctuating, or abruptly suspended; and in times of adversity, which frequently recur, men, drawn hither by the prospect of high wages, however short-lived such prosperity may prove, migrate in search of employment to other districts, or are removed to their former homes. In the iron and coal districts of South Wales, these colonies are collected at two points – the mountain sides, at which the minerals are raised, and the shipping ports, at which the produce of the mines is exported."

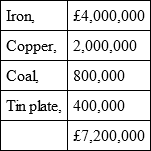

It appears that the total value of shipments from the counties of Monmouth, Glamorgan, and Carmarthen, in metals and minerals, during the year 1847 was, in round numbers, as follows: —

The copper specified above is not copper found in Wales, but that which is brought to Swansea, and other ports of Glamorgan and Carmarthen, for the purpose of being smelted, and then reshipped for various parts of the world, principally to France and South America. This trade gives occupation to a large population in those districts, and it forms one of the few branches of British manufactures, in which no very great fluctuations have been experienced during the last few years. It is, indeed, estimated that more than three-fourths of all the copper used on the face of the globe is smelted in the South-Welsh coal-field. But how prosperous soever may have been the condition of the great capitalists and iron-masters in South Wales, it does not appear that, with two or three bright exceptions, they have done much to ameliorate the condition of the people in their employment, – and even, in the present unsettled state of the world, the influence upon their hearts, of the metals they deal in, may be but too evidently seen. We find a most ingenious and important passage in Sir T. Phillips' work upon this subject, full of sound philosophy and excellent feeling. He observes: —

"The wilderness, or mountain waste, has been covered with people; an activity and energy almost superhuman characterise the operations of the district; wealth has been accumulated by the employer; and large wages have been earned by the labourer. Thus far the picture which has been presented is gratifying enough; but the more serious question arises – How have the social and moral relations of the district been influenced by the changes which it has witnessed? May it not be said with truth, that the wealth of the capitalist has ordinarily ministered to the selfish enjoyments of the possessor, whilst the ample wages earned in prosperous times by the labourer have been usually squandered in coarse intemperance, or careless extravagance? Prosperity is succeeded periodically by those seasons of adversity to which manufacturing industry is peculiarly exposed; when the labourer, whose wants grew with increased means, experiences positive suffering at a rate of wages on which he would have lived in comfort, had he not been accustomed to larger earnings. Crowded dwellings, badly-drained habitations, constant incitements to intemperance, and, above all, association with men of lawless and abandoned character, (who so frequently resort to newly-peopled districts,) are also unfavourable elements in the social condition of this people. To those influences may be added, the absence of a middle class, as a connecting link between the employer and the employed; the neglect of such moral supervision on the part of the employers as might influence the character of their workmen; and the want of those institutions for the relief of moral or physical destitution – whether churches, schools, almshouses, or hospitals – which characterise our older communities. Wealth accumulated by the employer is found by the side of destitution and suffering in the labourer – often, no doubt, the result of intemperance and improvidence, but not seldom the effect of those calamities against which no forethought can adequately guard; and when no provision is made for the relief of physical or moral suffering, by a dedication to God's service, for the relief of His creatures, of any portion of that wealth, to the accumulation of which by the capitalist the labourer has contributed, it will be manifest that the social and political institutions of our land are exposed to trials of no ordinary severity in these new communities.

"We live in times of great mental and moral activity. In the year which has now reached its close, changes have been accomplished, far more extensive and important than are usually witnessed by an entire generation of the sons of men; and around and about us opinions may be discerned, which involve, not merely the machinery of government, but the very framework of society: and these opinions are not confined to the closets of the studious, but pervade the workshop and the market, and interest the men who fill our crowded thoroughfares. In former ages, as well as in other conditions than the manufacturing in our own times, social inequalities may have presented themselves, or may still exist, great as those which characterise, in our own age, the seats of manufacturing labour; and the lord and vassal of the feudal system may have exhibited, and the squire and the peasant of some of our agricultural districts may still present, as wide a disparity of condition, as exists at this day between the master manufacturer and the operative; but the antagonism of interests, whether real or apparent, between the manufacturer and the operative, is altogether unlike that simple disparity of condition which may have perplexed former serfdom, or may excite wonder in the agricultural mind of our own age. To the eyes and the contemplations of the serf, as of the peasant, the lord or the squire was the possessor of wide and fertile lands, which he had inherited from other times, and which neither serf nor peasant had produced, but which both believed would minister to their necessities, whether in sickness or in poverty, because neither the castle-gate nor the hall-door had ever been closed against their tales of suffering and woe. Neither the ancient serf, nor the modern peasant, witnessed that rapid accumulation of wealth, which is so peculiarly the product of our manufacturing system, and saw not, as the operative does, fortunes built up from day to day, which he regards as the creation of his sweat and labour – and at once the result and the evidence of a polity which fosters capital more than industry, and regards not the poverty with which labour is so often associated. Different ages and conditions produce different maxims. The modern manufacturer is not a worse (he may be, and often is, a better) man than the ancient baron, but he has been brought up in a different philosophy. By him, the operative is well-nigh regarded as a machine, from whom certain economical results may be obtained – who is free to make his own bargains, and whose moral condition is a problem to be solved by himself, because, for that condition, no duty attaches to his employer, who has contracted with him none other than an economical relation. Yet, is there not danger that, in pursuing with logical precision, and with the confidence of demonstrated truths, the doctrines of political economy, we may forget duties far higher than any which that science can teach – duties which man owes to his fellow, and which are alike independent of capital and labour? It is no doubt true, that men who earn large wages, whilst blessed with health and strength, and in full employment, ought to make provision for sickness, old age, or want of work; but suppose that duty neglected, even then the obligation attaches to the employer to care for those of his own household. In old communities, too, the proportion must ever be large of those who, in prosperity, can barely provide for their bodily wants, and, in adversity, experience the bitterness of actual want in some of its sharpest visitations. To the humble-minded Christian, who has been accustomed to consider the gifts of God, whether bodily strength, or mental power, or wealth, or rank and influential station, as talents intrusted to him, as God's steward, for the good of his fellow-creatures – afflicting, indeed, is the spectacle of wealth, rapidly accumulated by the agency of labour, employed only for self-aggrandisement, with no fitting acknowledgment, by its possessor, of the claims of his fellow-men.