Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848

Look at it in any light you please, the change is fraught with danger. We have enlarged somewhat on the score of inconvenience – for we thoroughly feel and resolutely maintain that the practical inconvenience is great – but the other results we have referred to are inevitable and are infinitely worse. Tampering with the laws of nature is not permitted, even to the most sapient of town councils; and, as they cannot wash the Ethiopian white, so neither need they try to control the progress of the sun, and to prove that great luminary a liar. Surely, they have plenty to do without interfering with the planetary bodies? We really thought better of their patriotism; nor could we have expected that they would falsify the host of heaven in order to take their future time from some distant English clock. So soon as the whole of the world is ripe for an uniformity of time, and contented to adopt it, we may then possibly become acclimated to the change, and rise at midnight, to go about our nightly, not daily duties, without a murmur. But pray, in this matter, let us at least secure reciprocity. If we are to be dragged from our beds at untimeous hours, let the rest of the population of the globe suffer to a similar extent; for in community of suffering there is always some kind of dim and indefinite comfort. We are rather partial to bagmen, and would endure something, though not this, to accelerate their progress; but why should the whole Scottish nation be made a holocaust and an offering for our weakness? Falstaff, who, whatever may be said of his valour, was a remarkably shrewd individual, might give a lesson to our civic dignitaries. He counted the length and endurance of his imaginary combat with Percy, by Shrewsbury clock, and did not seek to extend his renown by superadding to it the benefit which might have been derived by a reference to Greenwich time. Let us do the like, and submit to the ordinances of Providence – not try to oppose them by any vain and extravagant alteration. Without the least irreverence, because we hold that the whole profanity – though it may be unintended – is on the other side, let us ask the Town Council of Edinburgh, whether they consider themselves on a par with the great leader of Israel, and whether they are entitled to say "Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon, and thou, moon, in the valley of Ajalon?" And yet, what is their late move, but something tantamount to this? They have declared against the order of nature, and such a declaration must imply a species of gross and unwarrantable presumption.

And now, Messieurs of the Town Council of Edinburgh, what have you to say for yourselves? Are we right, or are we wrong? – have we failed, or have we succeeded in making out a lease against you? We think we can discern some symptoms of a corporate blush suffusing your countenances; and, if so, far be it from us to stand in the way of your repentance. We are willing to believe that you have done this from the best of possible motives, but without forethought or consideration. You probably were not aware Of the consequences which might and must arise from this singular attempt at legislation. Be wise, therefore, and once more succumb, as is your duty, to the established laws and harmony of nature. Leave the planets alone to their course, and be contented to observe that time which is indicated and proclaimed from heaven. Recollect wherein it is written that the sun, and moon, and stars were set in the firmament of heaven to rule over the day, and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness. By no possible sophistry can you pervert the meaning of that wholesome text. Why, then, should you act in opposition to it, and introduce this element of disorder among us? Go to, then, and retrace your steps. Put the clocks backward as before. Let the shadows be straight at mid-day. Leave us our allotted rest, for it is sweet and pleasant. Defraud us not of our inheritance. Let our children not be born before their time. Let the miserable malefactor live until the last moment of his allotted span. Preserve the Sunday intact, and let us hear no more of such nonsense. Why should you be wiser than your forefathers? If any man had told them to alter their time from England, they would have collared the seditious prig, and thrust him neck and heels into the Tolbooth. When grim old Archibald Bell-the-Cat was Provost, no man durst have hinted at Greenwich time on pain of the forfeiture of his ears; for, notwithstanding his performances at Lauder Bridge, Bell-the-Cat was a Christian, the father of a bishop, and knew his duties better than rashly to interfere with Providence. Restore our meridian, and, if you are really anxious to do your duty, occupy yourselves with meaner matters. It would much conduce to the comfort of the lieges, if, instead of directing the course of the sun, you were to give occasional orders for a partial sweeping of the streets.

A MILITARY DISCUSSION TOUCHING OUR COAST DEFENCES

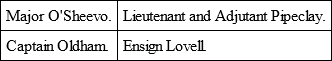

Scene. —A mess-room after dinner, from whence the members have departed, except four, who draw round the fire.

PERSONÆ

Oldham. – Well, Lovell, my boy, so you prefer the claret and the old Fogies this time to the sparks in the barrack-rooms; we feel the compliment, I assure you. There comes a clean glass: now, stir the fire; that's a good fellow. – I'll do as much for you, when I'm your age.

Lovell. – Why you see, Oldham, they say you old hands won't let out while all the mess are here, and you keep your opinions and experiences for these cosy little horse-shoe sittings. I should like to pick up a little soldiering, if I could, and so have ventured to outsit the rest of them.

O'Sheevo. – Ye're right, ye're right. A man that comes to value his claret early, has all the advantages of experience, without buying them dear. An old head upon young shoulders, in fact.

Pipeclay. – And, you see, the youngster has an eye to a little military information: that's right.

Lovell. – Why, these rumours of invasion make one look about him. If the French come, of course we shall give 'em an infernal good licking; but I am anxious to get an idea what sort of thing it will be, and I daresay you talk a good deal of these matters.

O'Sheevo. – Ah! them French! Oldham, ye don't expect they'll come to spend next Christmas with us?

Oldham. – There's no saying what the rascals might be at; and as Lovell has broached the subject, we may as well talk it over.

O'Sheevo. – Bravo! so we will: how say you, Pipeclay?

Pipeclay. – By all means. You know I mentioned last night how ill I thought our formations adapted for manœuvring against a hostile force on the coast.

Oldham. – My dear Pipeclay, it is the misfortune of a long peace, and a theoretical education, that they narrow the mind to strain at matters of detail, and to neglect the greater consideration, what is to be done – not how should we do it. Now, in the old second battalion of the 107th, the lads were more apt to talk of the work than the drill-book, and a finer or more dashing set never wore scarlet.

O'Sheevo. – Devil a doubt of it: not a man that wouldn't finish his three bottles before he'd think of stirring; and as for the seasoned files, the night was always too short for 'em. There's no saying what those men might have achieved, if they could have found the time.

Lovell. – But if the French —

Oldham. – Excuse me, Lovell, – I know something about the French, if three years in the Peninsula could give knowledge; and I'll tell you, for a fact, whatever you may hear said, that the organisation of the French army —

Pipeclay. – What! with that slovenly style of marching?

Oldham. – Never mind the style of marching: I say, that whether in the field, in camp, or in quarters —

O'Sheevo. – Devilish bad quarters they'd be sometimes, in them same campaigns, eh, Oldham? Short commons, eh?

Oldham. – Short commons! sometimes no commons at all!

O'Sheevo. – Thin claret?

Oldham. – Thin! the devil a drop. Sherry sometimes, of a quality according to our luck; but for claret we had to keep our stomachs till we got over the Pyrenees; – then, I may say, it ran in the rivers.

O'Sheevo. – The devil it did! Then I hope the next Peninsular expedition will sail direct for the coast of France.

Lovell. – But if this invasion —

Oldham. – Well, now, – look here. Well, here's Cherbourg, this glass, do you see? well then, this is Portsmouth, this other – and this dirty one, if I can reach it – damn it, I've broke my own, stretching, across the table.

O'Sheevo – Pipeclay. – Two for one! Two for one!

Oldham. – Well, never mind; 'twas awkward. We don't stand the jokes the old 107th used to cut: there, if you only made the smallest chip in the stem of a glass, you were stuck for your new pair, while the damaged one did duty as well as ever. There wasn't a glass in the mess that hadn't reproduced itself in double at least nine times.

O'Sheevo. – By the powers! that beats the phaynix, who never became twins, that I heard of. I'd not have stood it from any one. A glass that I broke and paid for, I'd consider my own intirely.

Pipeclay. – They had no right to put a glass on the table after it had been paid for; the regulations wouldn't allow it.

Oldham. – Oh! nobody knew any thing about the regulations in the old 107th. The colonel was a trump, and the lads were trumps, so they followed suit, and no lawyering.

Pipeclay. – A colonel has no right to enforce an unjust charge.

Oldham. – Well, perhaps not; but in our days we never troubled our heads about what was just or unjust. It's a bad sign of a corps when men begin to talk of their rights.

Lovell. – True, Oldham; you were saying, suppose that Cherbourg, the other Portsmouth – here's a third glass for you to complete.

Pipeclay. – I beg your pardon one minute, Lovell. I wish to convince Oldham that there is some advantage in knowing how to assert your own rights.

O'Sheevo. – I deny that in toto. The Ballyswig estate would have been in the O'Sheevo family to this day, if my great-aunt hadn't wished to assert her right to a haycock, which brought the title in question, and caused us to lose the whole property.

Pipeclay. – But if another had a just claim?

O'Sheevo. – Just humbug! The opposite side retained Counsellor Curran, who'd have persuaded a jury out of their Sunday waistcoats, with a five-shilling piece in the pocket of each.

Oldham. – Well, well. Now, look here, Lovell. This, as I said, is Cherbourg – this Portsmouth. Ellis, of the staff corps, used always to illustrate this way; did you ever meet him?

Lovell. – What! the owner of May-Bee, who won the military steeple-chase, two years ago? To be sure, I did: devilish sharp fellow he was too.

Pipeclay. – I don't know that: he broke down in some charges he preferred against Sergeant O'Flinn of the Royal County Down, who was acquitted by a general court-martial. A fellow who does that, may be a very good fellow, but can't have much head-piece.

Lovell. – May-Bee was a pretty piece of goods though. I saw the poor thing break her back last spring, under Jack Fisher of the carabineers: Jack nearly went out at the same time. Devilish sharply contested thing, till poor May-Bee's accident. Jack was picked up, – dreadful fall, as the papers said – gallant captain – small hopes of recovery – be universally regretted through the regiment – popular qualities – and that sort of thing; but somehow he marched to Nottingham at the head of his troop, a fortnight after, worth fifty dead men.

Pipeclay. – What do you value a dead man at, Lovell?

O'Sheevo. – If a thing's worth what it'll fetch, a dead man's value wouldn't burst the Exchequer.

Lovell. – Thank you, Major, for getting me out of that; the Adjutant was going to bring me up rather straitly.

O'Sheevo. – He's the very boy to do that. A bigoted ram's horn under his hands, would be forced to relinquish its prejudices. Nobody stoops to conquer in his academy. Send for another jug, and we'll go on with our discussion. Smart letter that of the old Duke's.

Oldham. – Who'll be commander-in-chief when the old Briton dies?

Pipeclay. – It'll depend upon the ministry of the day, which I hope will be a distant one. If he could only anticipate his posthumous fame now, how complete would be his glory.

O'Sheevo. – Sure, he's got his posthumous fame already: he's not obliged, like the ancients, to immortalise himself by committing suicide.

Lovell. – Certainly not, Major. Well, you know the Duke sees the necessity of defending our coasts —

Pipeclay. – And of increasing the army. I have a plan of my own for raising men, which I shall propose, some day or other, to the Horse Guards.

Oldham. – There's no difficulty in getting men; any quantity may be raised in Ireland.

O'Sheevo. – That's true, because any quantity are knocked over every day there; but they, poor men! are beyond the skill of even an adjutant.

Pipeclay. – At any rate I should like to give my system a fair trial.

O'Sheevo. – I have no opinion of systems; I've known many men entirely ruined by them.

Pipeclay. – How so, Major?

O'Sheevo. – Why, I knew a man who used to get a little jolly two or three times a-week, as occasion invited. Some well-meaning friends reproached him with the irregularity of his life, and pestered him to adopt a system, which, for the sake of peace and quietness, he at last did, and got blazing drunk every night; his own spirit didn't like the foreign invasion, and evacuated the place – that was system!

Lovell. – We don't much relish the idea of foreign invasion ourselves.

Pipeclay. – Let 'em come. If they intend to get a regular footing here, they would probably make a dash at Portland island.

Oldham. – Now my idea is this. Suppose them embarked in steamers, and starting for a point on our coast, – a few old fellows, who know what Frenchmen are made of, are stationed at all the landing-places, while a railway communication enables them to be quickly collected in one point.

Pipeclay. – I should object to old fellows as unfit for such sharp duties: active, intelligent young men would be better.

Oldham. – Pshaw! what's theory against Frenchmen? give me the old second battalion of the 107th before all the boys in the service.

Pipeclay. – And give me smart youngsters, who would move.

Oldham. – I'd like to see such Johnny Raws oppose a landing.

Pipeclay. – It stands to reason they must be better than a parcel of old worn-out sinners.

O'Sheevo. – Bravo! I'd like to hear this question fairly handled. You see, Lovell, that's the advantage of military breeding; we can discuss these topics without the rudenesses that you observe in civil life. Every man, young or old, may give his opinion, and be patiently listened to at a mess table.

Lovell. – It is certainly a great advantage.

Oldham. – I must maintain the superiority of veteran troops for all important duties; – you see a parcel of recruits would play the devil, – it's all stuff!

Lovell. – But, if I may be allowed to remark —

Oldham. – You, sir! damme! what should you know about it? What are you, eh? A stripling, a mere stripling. By Jove, sir, if you had been in the 107th, you would have seen what they thought of such forwardness.

Lovell. – You really mistake me, – I had no intention —

O'Sheevo. – Well, well; but you mustn't be obstinate you know, my boy, in matters that you can't possibly know much about; you can never learn any thing that way.

Pipeclay. – You should have a little modesty, Lovell.

O'Sheevo. – We're a liberal set of fellows here; but, by Jove, Lovell, I've known many a man that would have asked you to a leaden breakfast. Young Spanker of the 18th was called out by old Mullins for only asking him to repeat the number of oysters he said he ate in his great bet with M'Gobble. They fired six shots without effect, and Mullins was thought very lenient in not asking for an apology or the seventh.

Oldham. – Oh! the service would go to the devil if youngsters were allowed to lay down the law.

Pipeclay. – That would never do.

Oldham. – A strange file was that old Mullins you were talking of. Our second battalion was quartered with the 18th once, in Chatham barracks, when there were some memorable sittings.

Pipeclay. – I saw old Mullins once only, and then I could form little opinion of him, as he was half screwed.

O'Sheevo. – Half screwed! you must be mistaken.

Pipeclay. – I assure you I am rather under the mark in saying half screwed.

O'Sheevo. – Ah! I knew he never made so near an approach to sobriety as to be half screwed.

Oldham. —He would have been the fellow to receive the French! Come, now, Lovell, I'll show you, if you won't be obstinate and contradictory.

Lovell. – Upon my word, Oldham —

Oldham. – There you, fly out again now; it's impossible to do any thing with a youngster unless he has a tractable disposition. Here now, as I said, is Cherbourg, – here Portsmouth, – this little streak that I draw with my finger, the Channel. Jersey is somewhere there by the devilled biscuits; dy'e understand, Lovell?

Lovell. – Thank you, I do.

Oldham. – Good. Then this is our coast well manned, throughout its length, with troops: steady tried troops, mind, none of your gaping, staring boys: – well protected.

Pipeclay. – How protected?

Oldham. – How should I know? The engineers do that; of course they'd protect 'em with glacis, or ravelins or tenailles, or some of those damned jawbreaking named things; – well protected by works and cannon.

O'Sheevo. – Did you see that extraordinary cannon that West made in the mess-room this morning?

Pipeclay. – Ah! yes, – not bad, but I've seen finer strokes than that. You should have seen Legge of the 32d play.

Lovell. – Or Chowse of the artillery; by Jove! how he knocks about the balls! like an Indian juggler.

O'Sheevo. – Both good hands; ye're not a bad fist at billiards yourself, Oldham.

Oldham. – I seldom play now; – getting old; – played many a good match in the 107th's mess-room; but I think I could astonish Master West.

Pipeclay. – Well, if he'll play a match, I don't mind backing him against you even.

O'Sheevo. – And I'll go five to four on the youngster to make the thing worth your while.

Oldham. – Oh! no, no; 'twouldn't do for me to be playing matches with a raw recruit like that: 'twouldn't be dignified.

O'Sheevo. – Would it be more dignified if I said three to two?

Oldham. – Say two to one and I don't mind a rubber; – one rubber, remember.

O'Sheevo. – Done then. Let's have it to-morrow, if we can. West comes off guard in the morning, so there's the more chance of his being steady and willing to play; when they get hold of him overnight, he's always shaky and sulky next day till four or five o'clock. A bad constitution is a sad tell-tale under a red coat; a bishop chokes, or an anti-corn-law leaguer is attacked with pleurisy from his exertions in the cause of humanity; a lawyer's nose gets red from having his mind continually on the stretch; but if an ensign's colours only tremble a little in a strong gale, he's set down for a hard goer.

Pipeclay. – It's a great thing to be able to carry one's liquor well.

O'Sheevo. – Rather it's a dreadful misfortune when you can't. I always fancy that when a man can't show a bold face the morning after, he's been a great sinner.

Oldham. – Or that his forefathers have been so; I believe that posterity have to expiate the sins of their ancestors.

O'Sheevo. – But, as a man can neither be his ancestors nor his posterity, I don't see that he need mind that.

Pipeclay. – His ancestors' posterity is surely his affair.

O'Sheevo. – It's quite enough for a man to think of his own posterity without minding that of his ancestors.

Pipeclay. – He can't well help minding his ancestors when he daily and hourly feels the effects of their indiscretions.

O'Sheevo. – But d'ye mean to say that if all his ancestors were fast men, the whole of their diseases would be accumulated on his shoulders?

Pipeclay. – Not exactly. These things wear out in time, or are got rid of by crossing the breed; the nearer in time a man is to his rollicking ancestor, the more plainly he shows the hereditary taint.

O'Sheevo. – Then if he's his contemporary he's as bad as himself. I don't think, though, that my father showed the want of the Ballyswig estate a bit more than I do. Bad luck to my old aunt who forgot her successors though her ancestors remembered her.

Oldham. – Buzza that jug, Lovell, and touch the bell for another; these discussions make one thirsty.

O'Sheevo. – Thirst is nothing here to what it is in the tropics. By Jove! how I used to suffer at Jamaica.

Lovell. – Nature is said to have there provided for the craving by a bountiful supply of water. The name Jamaica signifies, I believe, the "Isle of Springs." You had excellent water there, Major, had you not?

O'Sheevo. – I always understood the water was very good, but I can't exactly remember that I ever tasted it. Nature is an affectionate mother, but there's no nourishment in her milk, so I put myself out to nurse upon sangree and portercup.

Pipeclay. – Nasty, unwholesome stuff; there's a yellow fever in every glass of it.

O'Sheevo. – It may be one of the ingredients; but that's no matter, if it's well mixed, because the other things correct it.

Oldham. – Our old second battalion buried I don't know how many in the seven years they spent out there. They always took the more intricate mixtures in the day time; – madeira and champagne at dinner, claret after, and topped up with brandy and water; after which they adjourned to settle, in the morning light, any little affairs of honour that had turned up in the evening.

Lovell. – Were these of so regular occurrence?

Oldham. – Seldom missed a night. The old cotton tree outside the mess-room, at Stoney Hill, was always one of the stations; and as full of bullets as a pudding is of plums. It was settling every thing before the meeting separated that made us such a united jolly set of fellows.

Pipeclay. – How much better we do things in the present day!

Oldham. – Another of your modern prejudices. How can any man of spirit think the investigations, explanations, and newspaper correspondence as creditable as settling the matter off-hand and like gentlemen?

Pipeclay. – But a duel does not always settle the right and wrong of an affair; and surely the party in the wrong ought to be the sufferer. Human life has a higher value than in old times; and, therefore, to avoid the casualties caused by duels, the laws punish the duellist.

O'Sheevo. – That's just it. In old times, if a man was killed there was an end; but now, to show the value of human life, the law hangs the survivor. The fact is, they find it necessary to thin the population, and so they take two for one, as we do with the glasses.

Oldham. – I'm afraid, Pipeclay, you and I will never agree in these matters. It's a pity you never had the advantage of seeing a little active service, which would have enlightened you far more than all my preaching. We'll hope better things for these youngsters before they become irretrievably bigoted to these milk-and-water prejudices. Well now, Lovell, d'ye think you understand all I said about the French invasion? If you don't, ask, and I'll give you any explanation my experience supplies, with pleasure.

Lovell. – I don't exactly understand how you would proceed after guarding your coast, and the enemy being off and on the shore.

Oldham. – Why, man, you never will understand if you don't attend. Here have I been talking this hour and a half exactly on that point, and you know no more about it than if I had not said a word. You must see, Lovell, that if you are thinking about horses, and women, and all sorts of nonsense, while I'm talking to you, you never can make a soldier. You should have seen our boys in the 107th. They would sit for hours and hold their breaths, while some old fire-eater told 'em his adventures and gave 'em advice.

O'Sheevo. – Then they must have been as long-winded as he was.

Oldham. – Pshaw! Nothing of that sort ever seemed long-winded: the interest was thrilling, and every body was unhappy when a story was ended.