Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 61, No. 378, April, 1847

And the effect of this importation of foreign grain, from whatever cause it arises, necessarily is to prevent this absorption of rural pauperism by manufacturing capital, to which the Free-traders so confidently look for the adjustment of society after the change has been made. The nations who supply us with grain do not want our manufactures. They will not buy them. What they want, is our money. They have not, and will not have, the artificial wants requisite for the general purchase of manufactures for a century to come. Generations must go to their graves during the transition from rustic content to civilised wants. America has sent us some millions of quarters of grain this year, but there is no increase in her orders for our manufactures. On the contrary, they are diminishing. Even the Free Trade Journals now admit this; constrained by the evidence of their senses to admit the entire failure of all their predictions.12 The reason is evident. They want our money, and our money they will have; and if they find our manufactures are beginning to flow in, in enlarged quantities, in consequence of our purchase of their grain, they will soon stop the influx by a tariff. This is what we did, when situated as they are—it is what all mankind will, and must do, in similar circumstances. It was distinctly perceived and foretold by the Protectionists that this effect would follow from free-trade, and that, unless something was done to enlarge the currency to meet it, a commercial crisis would ensue. These words published a year ago might pass for the history of the time in which we now live:—"Under the proposed reduced duties during the next three years, and trifling duty after that period on all sorts of grain, there can be no doubt that a very great impulse will be given to the corn-trade. It being now ascertained, by a comparison of the prices during the last twenty years, that there is annually a difference of from twenty to thirty shillings a-quarter between the price that wheat bears in the British islands and at the shores of the Baltic, while the cost of importation is only five or six shillings a-quarter, there can be no question that the opening of the ports will occasion a very large importation of foreign grain. It may reasonably be expected that, in the space of a few years, the quantity imported will amount to four or five millions of quarters annually, for which the price paid by the importers cannot be supposed to be less, on the most moderate calculation, than seven or eight millions sterling. The experience of the year 1839 sufficiently tells us what will be the effect of such an importation of grain, paid for, as it must be, for the most part in specie, upon the general monetary concerns and commercial prosperity of the empire. It is well known that it was this condition of things which produced the commercial crisis in this country, led to three years of unprecedented suffering in the manufacturing districts, and, as is affirmed, destroyed property in the manufacturing districts of Lancashire, to the amount of £40,000,000."13

Lastly, the famine has taught the empire an important lesson as to Irish Repeal. For many years past, that country has been convulsed, and the empire harassed by the loud and threatening demand for the Repeal of the Union, and the incessant outcry that the Irish people are perfectly equal to the duties of self-government, and that all their distresses have been owing to the oppression of the Saxon. The wind of adversity has blown, and where are these menaces now? Had Providence punished them by granting their prayer—had England cut the rope, as Mr Roebuck said, and let them go, where would Ireland have been at this moment? Drifting away on the ocean of starvation. Let this teach them their dependence upon their neighbours, and let another fact open their eyes to what those neighbours are. England has replied to the senseless clamour, the disgraceful ingratitude, by voting ten millions sterling in a single year to relieve the distresses which the heedlessness and indolence of the Irish had brought upon themselves. We say advisedly, brought upon themselves. For, mark-worthy circumstance! the destruction of the potato crop has been just as complete, and the food of the people has been just as entirely swept away in the West Highlands of Scotland, as in Ireland, but there has been no grant of public money to Scotland. The cruel Anglo-Saxons have given it all to the discontented, untaxed Gael in the Emerald isle.

1

Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches, with Elucidations by Thomas Carlyle.

2

Take the following instance from the early and more moderate times of the Revolution, and wherein the most staid and sober of this class of people is concerned. When Essex left London to march against the king, then at Oxford, he requested the assembly of divines to keep a fast for his success. Baillie informs us how it was celebrated. "We spent from nine to five graciously. After Dr Twisse had begun with a brief prayer, Mr Marshall prayed large two hours, most divinely confessing the sins of the members of the assembly in a wonderful, pathetic, and prudent way. After Mr Arrowsmith preached an hour, then a psalm; thereafter Mr Vines prayed near two hours, and Mr Palmer preached an hour, and Mr. Seaman prayed near two hours, then a psalm; after Mr Henderson brought them to a sweet conference of the heat confessed in the assembly, and other seen faults to be remedied, and the conveniency to preach against all sects, especially anabaptists and antinomians. Dr Twisse closed with a short prayer and blessing. God was so evidently in all this exercise that we expect certainly a blessing."—Baillie, quoted from Lingard.

3

Adventures of the Connaught Rangers, from 1808 to 1814. By W. Grattan, Esq. London. 1847.

4

The Life and Correspondence of the Right Honourable Henry Addington, First Viscount Sidmouth. By the Honourable George Pellew, D.D., Dean of Norwich. 3 vols. J. Murray.

5

Εστιν αρα η αρετη εξιϛπροαιξετικη, εν μεσοτητιξυϛα τη προϛ ημαϛ ωριϛμενη λογω

6

The principle of rotation in office is a favourite crochet of the Democratic party, and is founded upon the Republican jealousy of power. General Jackson went so far as to recommend that all official appointments whatever should be limited by law to the Presidential term of four years. As it is, whenever a change of parties occurs, a clean sweep is made of all the officers of government, from the highest to the lowest. Custom-house officers, jailers, &c., all share the fate of their betters. It is only surprising that the business of the country is carried on as well as it is, under the influence of this corrupting system.

7

Viz. 5-1/2 per cent on all advances on cash or current accounts, and 1/2 per cent commission on all sums overdrawn.

8

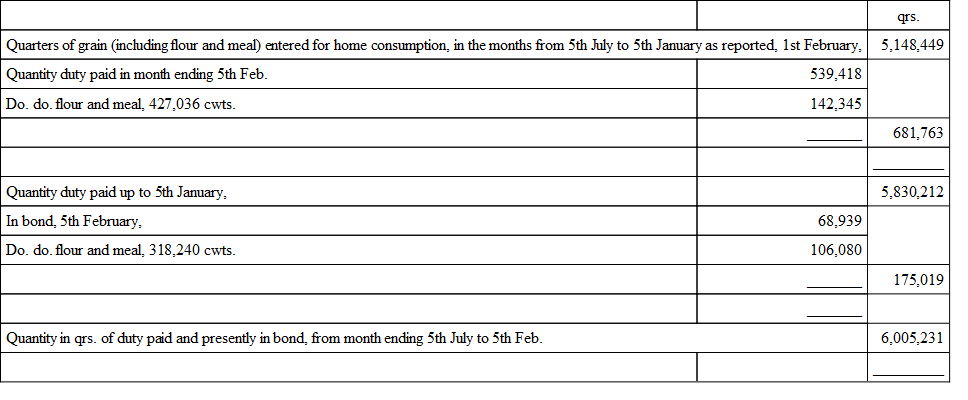

Table showing the quantity of grain, including flour and meal, entered for home consumption, from 5th July 1846, to 5th February 1847, from the London Gazette official returns:—

9

.

10

In 1840, the total amount was estimated at £180,000,000, of which £47,000,000, at that period, was for exportation, and £133,000,000 for the home market. As this £47,000,000 had swelled, in 1846, to £53,000,000, it is reasonable to suppose that those for the home market had undergone a similar increase, and are now about £200,000 annually.—See Speckman's Stat. Tables for 1842, p. 45.

11

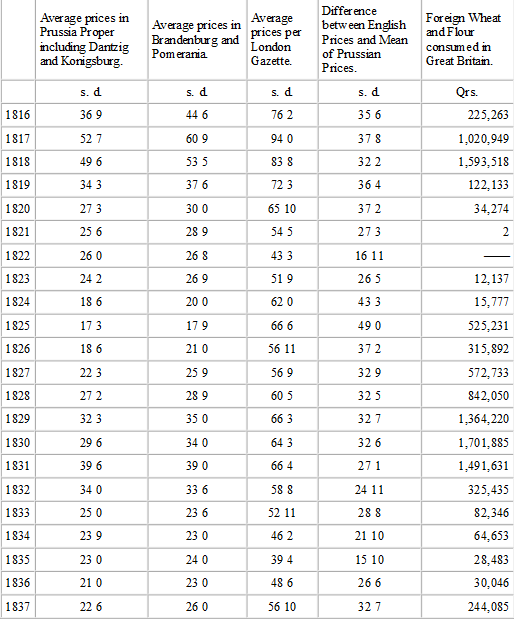

Table of Average Prices of Wheat in Prussia and in England, from 1816 to 1837.

12

"The excessive consumption of these and other articles has, however, only led to a drain of bullion to the extent of three millions and a half, while, upon a moderate computation, they would appear to call for three times that amount. This is to be accounted for by two facts—The first being that we have not imported, and paid for as much as we have consumed, since, conjointly with our importations, we have been steadily eating up former reserves, so that our stock of all kinds—coffee, sugar, rice, &c., are low; and, next, because we have diminished our importations of raw material in a remarkable degree, and hence, while paying for provisions, have lessened our usual payments on this score. Here, too, in like manner, we have been drawing upon our reserves. Our manufactures have been carried on with hemp, flax, and cotton, which had been paid for in former years, and we have left ourselves at the present moment short of all these articles, the stock of the latter alone, on the 1st of January last, as compared with the preceding year, being 545,790 against 1,060,560 bales. We are not only poorer, therefore, by all the bullion we have lost, but by all the stock we have thus consumed.

"This process cannot go on any longer. We have now no accumulations to eat into, and must, consequently, pay for what we use. Concurrently, therefore, with our importations of corn and other provisions, (which are now going on at a much greater rate, and at much higher prices than in 1846,) and just in proportion as they beget a demand for our manufactures, we must have importations of raw material. Large purchases of hemp and flax are alleged to have been made in the north of Europe, for spring shipment, and cotton from the United States is only delayed by the want of ships. Wool from Spain, and the Mediterranean, saltpetre, oil-seeds, &c., from India, and a host of minor articles, have also been kept back by the same cause, and will pour in upon us to make up our deficiencies directly any relaxation shall take place (if such could be foreseen) of the universal influx of grain. In this way, just as one cause of demand diminishes the other will increase, and the balance will be kept up against us for a period to which at present it is impossible to fix a limit.

"We thus see that no call that can possibly arise for our manufactures can have the effect of preventing a continuous drain of bullion. That a large trade will occur no one can doubt, but at present it is scarcely even in prospect. From India and China each account comes less favourable than before; from Russia we are told that 'no great demand can be expected for British goods under the present high duties' in that country; while even from the United States, the point from whence relief will most rapidly come, we hear of a shrewd conviction that we are approaching a period of low prices, and that, consequently, for the present 'the less they order from us the better.'"—Times, March 10, 1847.

13

England in 1815 and 1845, pp. v-vii. Preface to third edition, published in June 1846.