Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 70, No. 434, December, 1851

It is much to be regretted that Professor Johnston was unable to extend his tour to these granary States of the West. It would have been satisfactory to have had from him an estimate of their capabilities founded on actual survey and personal observation, instead of indirect inference. We are quite ready to admit, that many of the accounts of those regions which have reached us, drawn up to suit the purposes of speculators in land, are of very dubious authenticity, and, like the stage-coach in which Mr Dickens travelled to Buffalo, have "a pretty loud smell of varnish." But, on the other hand, we cannot discredit the official data supplied by the State papers – without at least stronger grounds than those inferences from general geological structure which Professor Johnston has adduced to disprove the alleged fertility of the State of Michigan. There can, of course, be no more valuable criterion of the natural agricultural value of a country than is afforded by its geology – provided the survey be sufficiently extensive and accurate. But it is difficult to follow those enthusiasts in the science, whom we occasionally find drawing the most startling deductions from very narrow data – and prophesying the future history of the territory, and even the character of its inhabitants, from a glance at the bowels of the earth, as the Roman augur foretold the fate of empires from the entrails of his chickens.

We find, for example, a writer of high standing in America accounting for a remarkable diminution in the amount of bastardy in Pennsylvania, some thirty years ago, by the fact – that the settlers at that time had got off the cold clays and on to the limestone! A Scottish geologist, with more apparent reason perhaps, has founded an argument for an extensive emigration of the Highlanders on the prevalence of the primitive rocks in the north and west of Scotland. It is only from a complete and systematic survey that we can venture to predicate anything with certainty of the future agricultural powers of a country; and, in the absence of such trustworthy data, we must be content to estimate the future wheat-productiveness of Michigan, as well as of the other States we have named along with it, from what we know of their present fertility, and of the vast extent that is still uncleared.

As to New York and the other old-settled States of the Union, which we are told do not now produce enough for their own consumption, are we to take it for granted that they are always to continue stationary, and to make no effort to keep pace with the growing demands of an increasing population? Professor Johnston, we observe in one passage, has qualified his opinion as to the prospective dearth of grain by this curious condition – "Provided no change takes place in their agricultural system." But what shadow of a reason can be given for supposing it will not take place? The area of New York State is only one-twelfth less than that of England, and is, at least, no way inferior as to climate or quality of soil. As far as material means go, it is quite capable of maintaining, under an improved culture, at least four times its present population of three millions. The only question is as to the will and ability of her people to develop these means; and on this point Professor Johnston's own work is full of multiplied proofs of the zealous and intelligent spirit of improvement which is extending rapidly all over the North-Eastern States. We find the central government of the Confederation occupied in organising the plan of an Agricultural Bureau on a scale worthy of a great and enlightened nation – a work that contrasts in a very marked way with the studious neglect which such subjects meet with from the government of this country.4 We find the several State legislatures anxiously encouraging every species of improvement – that of New York, in particular, devoting large grants to the support of exhibitions; preparing to found an Agricultural College; distributing widely and gratuitously the annual public reports on the state of agriculture; and, finally, sending to Europe for a celebrated chemist to assist in maturing their plans, and sitting – senators and great officers of state – at the feet of a British Gamaliel, laying down the law to them on the true principles of the all-important science of agriculture. Nor are the owners of the land asleep. It is a strong indication of their growing desire for information, that seven or eight agricultural periodicals are published in the State of New York alone. Professor Johnston found no less than fifty copies of such papers taken regularly in a small town in Connecticut of some two thousand inhabitants; and he had occasion to observe, in his intercourse with the farmers of New York, their general acquaintance with the geology of their country, and its relation to the management of their lands. Their implement-makers, who had already taught us the use of the horse-rake, the cradle-scythe, and the improved churn, have recently outstripped us by the invention, or at least the great improvement, of the reaping-machine, the advantages of which are so appreciated in the country of its origin that at Chicago 1500 of M'Cormick's machines were ordered in one year. In short, the proverbial energy, perseverance, and sagacity that distinguish our Yankee friends, seem now to be all directed towards effecting a change of system in the management of land; and the true question is, not whether the hitherto laggard progress of American agriculture is to be quickened in future, but whether we shall be able to keep pace with it.

But then Professor Johnston tells us that improvement is expensive, and that every process for reviving the dormant powers of the soil, and preserving their activity, must necessarily be attended with an addition to the price of the produce, which will thus prevent its coming into competition with that of England. This view rests upon a fallacy, which we are sure the author must have drawn from his reading in political economy, and not from his experience as an agriculturist. It is an off-shoot from the rent-theory, (the pestilent root of so much error and confusion,) which, however, we shall not notice at present, further than by affirming, in direct contradiction to it, that improvements do not necessarily, nor generally, involve an increase of price. Even those which require the greatest outlay – even a complete system of arterial drainage all over the State of New York, instead of adding to the cost of wheat, may very probably reduce it, as it has certainly done in this country. But most of the improvements readily available in the Eastern States involve scarcely any expenditure at all. The most obvious and effectual is to save and apply the manure, which is now wasted or thrown away; and when that proves insufficient, abundant supplies of mineral manures are easily procurable. On the exhausted wheat-lands of Virginia, a single dressing of lime or marl generally doubles the first crop. Deposits of gypsum, and of the valuable mineral phosphate of lime, seem to be abundant both in New York and New Jersey. Again, in the former State, where the common practice is to plough to a depth of not more than four inches, the simple expedient of putting in the plough a few inches deeper would of itself add one-half to the return of wheat over a very large district.

On the whole, so far from seeing any reason to anticipate, with Professor Johnston, a material reduction in the quantity of our wheat imports from the States, we look rather to see it increased; and, at all events, we have no hesitation in saying, that to encourage our English farmers to expect a cessation of competition from that quarter is to deceive them with very groundless hopes.

We have already dwelt at considerable length on this topic, both because of the prominent place it occupies in Professor Johnston's volumes, and of the notice which his speculations upon it have attracted in this country.

It has been mentioned that a large proportion – probably not less than one-half – of the cereal food consumed in the States consists of maize and buckwheat. Mr Johnston always alludes to this fact, as if the use of these grains were a matter of compulsion – as if the Americans resorted to them from being unable to afford wheaten bread. Now, according to the information we have from other sources, the truth is just the reverse of this. We are told that in the Eastern and Central States, as well as on the West frontier and among the slave population, the various preparations of Indian corn are becoming more relished every year; and that the extension of its cultivation is to be attributed, not to the failure of the wheat crops, but to a growing preference for it as an article of food. In a less degree the use both of oats and buckwheat seems to be spreading in the States, as well as in our own colonies of New Brunswick and Canada East; and one can scarcely wonder at the taste for the latter grain, after reading the appetising descriptions our author gives of the crisp hot cakes, with their savoury adjuncts of maple-honey, which so often formed his breakfast during his wanderings. The general use of these three kinds of grain – maize, oats, and buckwheat – has somehow come to be considered by political economists as indicative of a low degree of social advancement. And yet we know that, in the countries suited to their growth, a given area of ground cultivated with any of them will return a greater quantity of nutritious food, at a smaller expense and with less risk of failure, than if it were cropped with wheat. We are told that the great objection to them is, that their culture is too easy. Professor Johnston touches upon this notion in some remarks he makes on the disadvantage of buckwheat as a staple article of food. The objections to it, he tells us, consist in the ease with which it can be raised, the rapidity of its growth, and the small quantity of seed it requires: it induces, he says, like the potato, an indolent, slovenly, and exhausting culture; and "it is the prelude of evil, when a kind of food that requires little exertion to obtain it becomes the staple support of a people."5 It may be noticed in passing, that, in point of fact, the results alleged are at least not universal; for, in regard to this very grain, we find its cultivation prevalent in some of the best-managed districts of the hard-working, provident, and intelligent Belgians. But taking the axiom as it stands, we cannot help suspecting that there is some fallacy lurking at the bottom of it. Misled by what we have observed of the Irishman and his potato diet, we have confounded the cum hoc with the propter hoc, and come to regard an easily-raised food as the cause of that indolence of which it is only the frequent indication. It were otherwise a most inexplicable contrariety between the physical and the moral laws which govern this world, that in every country there should be a penalty of social wretchedness and degradation attached to the use of that particular food which its climate and soil are best suited to produce. Can it be supposed that the blessings of nature are only a moral snare for us, and that, while she has given to the American the maize plant – oats to the Scotch Highlander – rice to the Hindoo – the banana to the inhabitant of Brazil – a regard for their social well-being requires each of them to renounce these gifts, and to spend their labour in extorting from the unwilling soil some less congenial kind of subsistence? Virgil has warned the husbandman —

"Pater ipse colendiHaud facilem esse viam voluit."But it were surely a dire aggravation of the difficulties of his task if his most plentiful harvest were also the most injurious to his advancement and true happiness. We cannot now, however, examine the grounds of a doctrine so paradoxical, and have adverted to it only to remark that it seems destined to meet with a most direct practical refutation in North America, where we find the habitual use of what we choose to consider the coarser grains associated with the highest intelligence and the most rapid development of social progress. There can be no doubt that the nature of the food generally used in any nation must exert an important influence on its prosperity; but it is difficult to understand how that prosperity should be promoted by the universal use of that variety which costs most labour. At all events, it is certainly a subject of very interesting inquiry, in reference to the increasing consumption among ourselves of wheat – the dearest and most precarious species of grain, much of it imported from other countries – and its gradual abandonment in North America, what effect these opposite courses may have on the future destinies of the two great branches of the Anglo-Saxon race.

Leaving this as a problem for political economists, let us now follow him in his visit to the British side of the St Lawrence. His brief three weeks' survey of the Canadas did not, of course, enable him to form any very intimate acquaintance with the condition of these provinces; and he prudently abstains from pronouncing any judgment upon the vexed topics of Canadian politics. His presence at the great exhibition, at Kingston, of the Agricultural Society of Upper Canada, gave him a good opportunity of estimating the progress that has been made in practical agriculture. The stock, as well as the implements, there brought forward in competition for the various premiums, amounting in all to £1000, gave most satisfactory indications of improvement; while the large attendance, and the interest taken in the proceedings, sufficiently showed that the inhabitants of the Upper Province are now awake to the necessity of agricultural improvement as the main source of their future prosperity. In a country where eighty per cent of the whole population are directly engaged in the cultivation of the soil, the land interest is, or ought to be, predominant. But the bitter animosity of political parties, and the abortive attempts of government to soothe and reconcile them, have hitherto stood much in the way of any combined effort towards the encouragement of improved cultivation. The art of husbandry is not likely to thrive in a country where every man is bent on proving himself a Cincinnatus. Of late, however, public spirit has shown symptoms of taking a more wholesome direction; and, notwithstanding occasional ministerial crises and political explosions, which we on this side the water are sometimes puzzled to understand, all parties in the province seem now fully aware that the development of the vast resources of their fertile soil is the only road to permanent prosperity. The encouragement of local competitions, the provision for systematic instruction in agriculture in the colleges – which Professor Johnston tells us is in progress – and the introduction of elementary lessons in the art as a regular branch of common school learning, are all steps in the right direction. It is precisely in such a community as that of Canada that the last-mentioned kind of instruction is really of essential benefit. From the last census of Upper Canada, it appears that there are sixty thousand owners of land in the province, and only ten thousand labourers without land. The great majority of the boys in the ordinary schools will become proprietors, and, at the same time, cultivators; and, in such circumstances, it is of the utmost importance that the youth should acquire betimes a competent knowledge of the principles on which his future practice is, or ought to be, founded – such knowledge as will, at least, enable him to, shake off the traditional prejudices and slovenly habits which his father may have imported with him from Harris or the County Kerry.

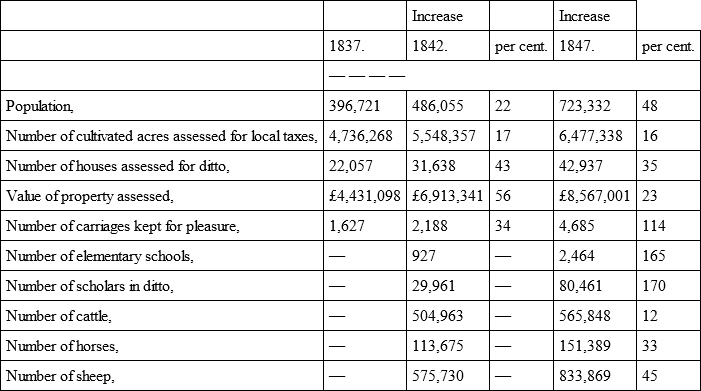

The querulous and depreciatory tone which our Canadian fellow-subjects are apt to employ in speaking of their country, and its prospects, is remarked by Professor Johnston as contrasting oddly with the unqualified adulation of everything – from the national constitution to the navy button – which one constantly hears from his republican neighbour. One consequence of this habit is, the existence of a prevalent but very mistaken notion that, in the march of social advancement, Canada has been completely distanced by the United States. Professor Johnston has been at some pains to demonstrate, and we think most successfully, that this impression is entirely erroneous. Indeed, if we only recollect the history of Canada for the last fifteen years – the disunion of her own people, and the reckless commercial experiments to which she has been subjected by the home government, the rapid strides in improvement – of the Upper Province especially – are almost marvellous. As a corroboration of what Professor Johnston has said on the subject, we have thrown together in the subjoined table, collected from the Government returns, some of the most striking and decisive evidences of the recent progress of Upper Canada. In certain particulars, no doubt, she is outstripped by some of those districts of the States to which from time to time extraordinary migrations of their unsettled and nomadic population have been directed. But putting such exceptional cases out of view, the inhabitants of Canada need fear no comparison with the Union in all the chief elements of national advancement.

PROGRESS OF UPPER CANADA, – 1837-47.

In looking at the great sources of wealth possessed by these provinces, our attention is at once arrested by the growing importance of the St Lawrence as an outlet to the produce, not only of the Canadas, but of a vast area of the States territory. With the exception, perhaps, of the Mississippi, no river in the world opens up so grand a highway for the industry of man as the St Lawrence, with the chain of vast lakes and innumerable rivers that unite with it in the two thousand miles of its majestic progress to the ocean. Never was there an enterprise more worthy of a great nation than that of surmounting the obstacles to its navigation, and completing the channels of connection with its tributary waters; and nobly have the people of Canada executed it. Taking into account the infancy of their country, and the amount of its population and revenue, it is not too much to say, with Mr Johnston, that their exertions to secure water-communication have been greater than those of any part of the Union, or any country of Europe. The improvements on the St Lawrence itself, and the canals connected with it, have already cost the colony two millions and a quarter sterling, in addition to the expenditure of £800,000 by the home government on the construction of the Rideau Canal. The results of this liberal but judicious outlay are already showing themselves, not only by the rapidly-increasing Canadian traffic on the St Lawrence, but by its drawing into it, year after year, a larger share of the commerce of the States. That the influx of trade from the south must ere long vastly exceed its present amount, is evident from a consideration of the gigantic projects already completed, or in course of construction, for effecting an access between the lakes and the fertile regions of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, &c., already spoken of, and thus saving the longer and costlier transit by the Mississippi. One of the Reports of the State of New York thus speaks of them: —

"Three great canals, (one of them longer than the Erie Canal,) embracing in their aggregate length about one thousand miles, are to connect the Ohio with Lake Erie; while another deep and capacious channel, excavated for nearly thirty miles through solid rock, unites Lake Michigan with the navigable waters of the Illinois. In addition to these broad avenues of trade, they are constructing lines of railroads not less than fifteen hundred miles in extent, in order to reach with more case and speed the lakes through which they seek a conveyance to the seaboard. The circumstance, moreover, is particularly important, that the public works of each of these great communities are arranged on a harmonious plan, each having a main line, supported and enriched by lateral and tributary branches, thereby bringing the industry of their people into prompt and profitable action; while the systems themselves are again united, on a grander scale, with Lake Erie as its common centre."

The various streams of the trade from the interior being thus collected in the lakes – which form, as it were, the heart of the system – there are two great channels for its redistribution and dispersion through the markets of the world. These are the St Lawrence, and the Erie Canal with the Hudson; and the vital question as regards the prosperity of Canada is, by which of these outlets will the concentrated traffic of the lakes find its way to the ocean? Mr Johnston has devoted considerable attention to this subject, and assigns two good reasons for believing that the St Lawrence is destined immensely to increase the share which it has already secured. In the first place, the American artery is already surcharged and choked up; – notwithstanding all the efforts that have been made to expedite the traffic on the Erie Canal, it has been found wholly inadequate to accommodate the immense trade pouring in from the west; and, secondly, the route of the St Lawrence, besides being the more expeditious, is now found to be the cheaper one. In a document issued by the Executive Council of Upper Canada, it is mentioned that the Great Ohio Railway Company, having occasion to import about 11,000 tons of railway iron from England, made special inquiries as to the relative cost of transport by the St Lawrence and New York routes, the result of which was the preference of the former, the saving on the inland transport alone being 11,000 dollars. There seems good reason to expect that a considerable portion of the Mississippi trade may be diverted into the Canadian channel; but putting this out of view altogether, it is certain that the navigation of this glorious river is every year becoming of greater importance to the United States, as well as to Britain: let us hope that it is destined ever to bear on its broad breast the blessings of peace and mutual prosperity to both nations.

After a rapid glance at Lower Canada, Professor Johnston crossed the St Lawrence, in order to complete the survey of New Brunswick, which, before leaving England, he had been commissioned to make for the Government of the colony. We have had no opportunity of seeing the official Report, in which he has published the detailed results of his observations; but the valuable information collected in these volumes has strongly confirmed our previous impression, that the resources and importance of this fine colony have never yet been sufficiently appreciated at home. With an area as nearly as possible equal to that of Scotland, it possesses a much larger surface available for agriculture. The climate is healthy and invigorating; it is traversed by numerous navigable rivers; its rocks contain considerable mineral wealth; and the fisheries on its coasts are inexhaustible. Imperfectly developed as its resources are, the trade from the two ports of St John's and St Andrew's alone, exceeds that of the whole of the three adjoining States of the Union – Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire – although its inhabitants do not number one-sixth of the population of these States. As to the fertility of the soil, Professor Johnston, by a comparison of authentic returns, shows that the productive power of the land already cultivated in the province considerably exceeds the averages of New York, of Ohio, and of Upper Canada – countries which have hitherto been considered more favoured both in soil and climate. By classifying the soils in the several districts, he has estimated that the available land, after deducting a reserve for fuel, is capable of maintaining in abundance a population of 4,200,000; while its present number little exceeds 200,000. In all the course of his travels, he met with but a few rare instances in which the agricultural settlers did not express their contentment with their circumstances; and although it seems still questionable whether farming on a large scale, by the employment of hired labour, can be made remunerative, the universal opinion of the experienced persons he consulted testified that, with ordinary prudence and industry, the poorest settler, who confines his attention to the clearing and cultivation of land, is sure of attaining a comfortable independence.

The question naturally occurs – How is it that, with all these natural advantages and encouragements to colonisation, and with its proximity to our shores, so very small a proportion – not more than one in sixty or seventy of the emigrants from Great Britain – make New Brunswick their destination? Professor Johnston, while he maintains that, taking population into account, New Brunswick is in this respect no worse off than Canada, adverts to several causes of a special nature which may have retarded its settlement. But the truth is, that the question above started leads us directly to another of far greater compass and importance – What is the reason that all our colonies taken together absorb so small a proportion of our emigrants compared with the United States? What is the nature of the inducements that annually impel so large a number of our countrymen to forfeit the character of British subjects, and prefer a domicile among those who are aliens in laws, interests, and system of government?