Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 70, No. 434, December, 1851

The truth is, that the system of railway management in this country has been, from the beginning to the end, decidedly bad. Each line, as it came into existence, was fostered by quackery and falsehood. The most extravagant representations were used to secure the adhesion of shareholders, and to procure the public support. Rival lines fought each other before the committees with a desperation worthy of the cats of Kilkenny, and enormous expenses and law charges were incurred at the very commencement. No economy whatever was used in the engineering, and no check placed on the engineers. In those days, indeed, an engineer of established reputation was a kind of demigod, whose doctrine, or, at all events, whose charges, it was sinful to challenge. But engineers have their ambition. They like viaducts which will be talked of and admired as splendid achievements of mechanical skill; and the most virtuous of the tribe cannot resist the temptation of a tunnel. Such tastes are natural, but they are fearfully expensive in their indulgence, as the shareholders know to their cost. The remuneration of these gentlemen was monstrous. In the course of a few years most of them realised large fortunes, which is more than can be said for the majority of the men who paid them. So was it with the contractors. Mr Francis tells us of many, "who, beginning life as navigators, have become contractors; who, having saved money, have become 'gangers,' realised capital and formed contracts, first for thousands, and then for hundreds of thousands. These are almost a caste by themselves. They make fortunes, and purchase landed estates. Many a fine property has passed from some improvident possessor to a railway labourer; and some of the most beautiful country seats in England belong to men who trundled the barrow, who delved with the spade, who smote with the pick-axe, and blasted the rock." With such statements before us, it is not difficult to see how the money went. Alas for the shareholders! Poor geese! they little thought how many were to have a pluck at their pinions.

Industry, we freely admit, ought to have its reward; but rewards such as these are beyond the reach of pure industry, as we used formerly to understand the term. These revelations may, however, be of use as indicating the direction in which a great part of the money has gone. We accept them as such, and as illustrations of that profound economy which was practised by the different boards of railway direction throughout the kingdom. Mr Francis, in his laudatory sketches of his favourite heroes, usually takes care to tell us that they are "sprung from the ranks of the people." Of course they are. Where else were they to spring from? Does Mr Francis suppose it to be a popular article of belief that they emerged from the bowels of a steam-engine? What he means, however, is plain enough. Judging from the whole tenor of his book, we take him to be one of those jaundiced persons who, without any intelligible reason beyond class prejudice, are filled with bile and rancour against the aristocracy, and who worship at the shrine of money. He grudges every farthing that the railway companies were compelled to pay for land; he bows down in reverence before the princely fortunes of the contractors. Every man to his own taste. We cannot truthfully assert that we admire the selection of his idols.

But what is this? We have just lighted upon a passage which compels us, in spite of ourselves, to suspect that our Francis is, at least, a bit of a repudiator, and that he would regard with no unfavourable eye another pluck at the shareholders. Here it is: —

"The assertion that land and compensation on the line to which Mr Robert Stephenson was engineer, which was estimated at £250,000, amounted to £750,000, appears to call for some additional remark; and the question which is now proposed is, how far the right is with the railroads to demand, and the passengers to pay an increased fare, in consequence of bargains which, unjust in principle, ought never to have been allowed? It is now a historic fact that every line in England has cost more than it ought. That in some – where, too, the directors were business men – large sums were improperly paid for land, for compensation, for consequential damages, for fancy prospects, and other unjust demands under various names. These sums being immorally obtained, is it right that the public should pay the interest on them? Is it just that the working man should forego his trifling luxury to meet them? Is it fair that the artisan should be deprived of his occasional trip, or that the frequenter of the rail should pay an additional tax?"

Is it fair that anybody should pay anything at all for travelling on the railways? That is the question which must finally be considered, if Mr Francis' preliminary questions are to be entertained. Because some part of the capital of the shareholders may have been needlessly expended, they ought in this view to receive a less amount of interest for the remainder! The silliness of the above passage is so supreme – the ignorance which it displays of the first rules of law and equity, regarding property, is so profound, that it is hardly worth while exposing it. It betrays an obliquity of intellect of which we had not previously suspected even Mr Francis. Pray observe the exquisite serenity with which this important personage opens his case: "The question which is now proposed!" Proposed – and for whose consideration? Not surely for that of the Legislature, for the Legislature has already pronounced judgment. Are the public to take the matter in hand, and decide on the tables of rates? It would seem so. In that case, we might indeed calculate upon travelling cheap, provided the rails were not shut up. But the whole of his remarks are as practically absurd as they are mischievous in doctrine. What right has Jack, Tom, or Harry to question the cost of his conveyance? Are there not, in all conscience, competing lines enough, independent altogether of Parliamentary regulations, to secure the public against being overcharged on the railways? On what authority does Mr Francis assume that a single acre of the land was paid for at an unjust rate? Mr Robert Stephenson's estimate, we take it, has not the authority of gospel. No engineer's estimate has. Their margin is always a large one; and it almost never happens that, when the works are completed, their actual cost is found to correspond with the hypothetical calculation. But the truth is, that the value paid for the land taken by railways is the only item of expense which cannot be justly challenged. The reason is plain. A railway company has in the first instance to prove the preamble of its bill – that is, it must show to the satisfaction of the Legislature that the construction of the work will be attended with public and local advantages. The settlement of the money question, regarding the value of the land, is reserved for the legal tribunals of the country. To complain of the verdicts given is to impugn the course of justice, and to cast discredit on the system of jury trial. Very wisely was it determined that such questions should be so adjudicated, because no reasonable ground of complaint can be left to either party. The decision as to the value of the land, and the amount of compensation which is due, is taken from the hands both of Ahab and Naboth, and their respective engineers and valuators, and intrusted to neutral parties, whose duty it is to see fair play between them.

We have done with this book. It has greatly disappointed us in every respect. As a repertory of facts, or as a history of the railways, it is ill-arranged, meagre, and stupid; and the sketches which it contains are so absurdly conceived, and so clumsily executed, that they entirely fail to enliven the general dulness of the volumes. At the very point which might have been rendered most interesting in the hands of an able and well-instructed writer – the period of the great mania – Mr Francis fails. His pen is not adequate to the task of depicting the rapid occurrences of the day, or the fearful whirl which then agitated the public mind. In short, he is insufferably prosy throughout the first four acts of his drama, and makes a lamentable break-down at the catastrophe. His work will fail to please any portion of the public, except the heroes whose praises he has sung. He has given them sugar, indeed; but, after all, it is a sanded article. We hope they will combine to buy up the edition, and thus fulfil the prophecy of Shakspeare – "Nay, but hark you, Francis: for the sugar thou gavest me – 'twas a pennyworth, was't not?" "O Lord, sir! I would it had been two." "I will give thee for it a thousand pound: ask me when thou wilt, and thou shalt have it." "Anon, anon, sir!"

1

The estimated produce of wheat in these five States in the year 1847 was 38,400,000 bushels.

2

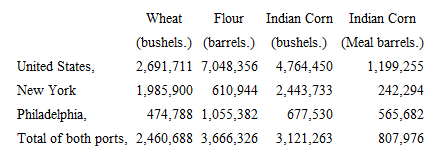

Quantity of bread-stuffs exported from the whole of the United States, and from the ports of New York and Philadelphia, in the years 1842-46 inclusive: —

3

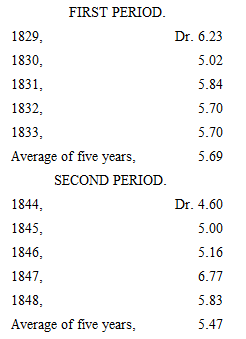

Comparative statement of the prices, per barrel, of best wheat flour at New York, (taken from the Monthly Averages) in 1829-33, and 1844-48: —

4

Vol. ii. p. 389.

5

Vol. i. p. 80.

6

Total number of registered emigrants for the twenty-one years from 1825 to

1845 inclusive 1,349,476 – Average, 64,260

Do. do. for the five years 1846 to 1850 inclusive, 1,216,557 – Average, 243,311

7

See Mr Smee's pamphlet on the Income-Tax.

8

By the leviathan steamers now building for the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Company. They are calculated to make from sixteen to eighteen miles an hour, which would reduce the sea-going part of the voyage to eight days two hours.

9

The mere physical pleasure of the upper voyage has been thus described – "No words can convey an idea of the beauty and delightfulness of tropical weather, at least while any breeze from the north is blowing. There is a pleasure in the very act of breathing – a voluptuous consciousness that existence is a blessed thing: the pulse beats high, but calmly; the eye feels expanded; the chest heaves pleasureably, as if air was a delicious draught to thirsty lungs; and the mind takes its colouring and character from sensation. No thought of melancholy ever darkens over us – no painful sense of isolation or of loneliness, as day after day we pass on through silent deserts, upon the silent and solemn river. One seems, as it were, removed into another state of existence; and all the strifes and struggles of that from which we have emerged seem to fade, softened into indistinctness. This is what Homer and Alfred Tennyson knew that the lotus-eaters felt when they tasted of the mysterious tree of this country, and became weary of their wanderings: —

' – To him the gushing of the waveFar, far away, did seem to mourn and raveOn alien shores: and, if his fellow spake,His voice was thin, as voices from the grave!And deep asleep he seemed, yet all awake,And music in his ears his beating heart did make.'If the day, with all the tyranny of its sunshine and its innumerable insects, be enjoyable in the tropics, the night is still more so. The stars shine out with diamond brilliancy, and appear as large as if seen through a telescope. Their changing colours, the wake of light they cast upon the water, the distinctness of the milky way, and the splendour, above all, of the evening star, give one the impression of being under a different firmament from that to which we have been accustomed; then the cool delicious airs, with all the strange and stilly sounds they bear from the desert and the forest; the delicate scents they scatter, and the languid breathings with which they make our large white sails appear to pant, as they heave and languish softly over the water." – (The Crescent and the Cross, vol. i. p. 210.)

10

The journey from Cairo across the desert by Suez, or at least thence by Gaza or Sinai to Jerusalem, is performed in the same manner as it was in the days when Eothen, Dr Robinson, and Lord Castlereagh described it. The only difference occurs in the route between Cairo and Suez, which is now performed on wheels in about twelve hours, and, in the course of eighteen months, is expected to be easily accomplished in two hours and a half by railway.

11

Kief: a word difficult to translate, but expressing perfect abandonment to repose; a dolce far niente which only Orientals can thoroughly achieve.

12

The Moslems being water-drinkers, are as curious about their streams as bons vivans are about their cellars. One of the Caliphs sent to weigh all the waters in his wide kingdom, and found that of the Euphrates was the lightest.

13

He was subsequently murdered, A. D. 62.

14

We must here notice the generosity with which Mr Walpole forbears to enlarge upon any subject in which he might anticipate the works of other travellers. For this reason he passes lightly over this interesting tour in the mountains of Koordistan, and only (to our regret) alludes en passant to a tribe of pastoral Jews, whom he and Mr Layard met on these mountains, following the spring (as the snows receding left fresh herbage for their flocks) up the mountains. When we consider how rarely pastoral Jews are met with, and that this was the very land wherein the lost ten tribes disappeared, and, moreover, that the elders of these people spoke the Chaldean tongue, we are much disappointed to hear no more of them.

15

The mystery relating to this community is so great that the laborious Müller, in his twenty-four books, has not attempted to penetrate it. And Gibbon, notwithstanding his acknowledged pleasure in painting scenes of blood, has treated the Order of Assassins very superficially. Marco Polo is, as usual, the most entertaining of authorities, as far as he goes; but it remained for Joseph Von Hammer to explore the faint vestiges of their strange story with vast and patient research. He has thrown together the results of his labours in a small volume, of great interest.

16

The Vulture's Nest.

17

Dais, Refik, and Fedavie.

18

De Regionibus Orient., lib. i. c. 28.

19

We do not yet know if any ceremony exists at the naming of the child.