Полная версия:

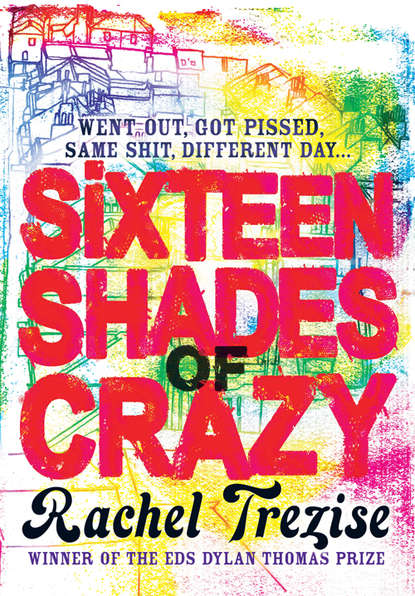

Sixteen Shades of Crazy

She squeezed a splodge of the gooey, honey-coloured make-up on to her palm and tilted her head towards the light. She almost didn’t recognize her reflection, had always imagined herself as the blurred, worried-looking image she saw in Niall’s pupils; a doting, fretting mother, clammy red cheeks, a band of sweat at her hairline. But in the mirror she looked close to human. She brushed mascara on her lashes with brisk strokes, stabbing herself in the eyeball when she heard her daughter shriek.

‘Angharad!’ she bellowed, flinging the kitchen door open, the mascara wand still clenched in her fist. Her adrenal glands opened, her heartbeat hopping. ‘Angharad? What’s wrong?’

James was sitting at his plastic drum-kit, pounding on the bass pedal, the force of each blow sending his orange fringe into the air. He was four years old, a sober child. When he was newborn, Siân worried he was mute. He lay in his cot, staring at the Artex ceiling, no reaction to touch or to noise. Infancy brought an occasional scrap of conservative speech.

Angharad was leaning against the edge of the table, slugging cherryade, one of the legs of her sky-blue dungarees rolled up to her knee, an impish glint in her emerald eyes. A robust and outgoing three-year-old. When the social worker called on her at two years, asking about her speech patterns, Angharad pointed at the bar of Dairy Milk poking out of the woman’s satchel. ‘Come on, lady,’ she said, licking her lips, ‘everyone has to share.’ She put the cherryade down on the table and let go of a long burp, stared brazenly at Siân. ‘James punched me,’ she said.

Siân reached for the kitchen roll and broke a sheaf away, dabbing it against her streaming eye. The shock was wearing off, the pain returning, like a hot poker stabbing into her pupil. ‘I think you’re lying again,’ she said, though she couldn’t quite remember the last time her daughter had lied. There were no lies in Siân’s house. There were fibs, like when Auntie Rhiannon came around in a miniskirt that didn’t hide her saggy, orange-peel skin, and they all told her she looked very nice. Siân threw the tissue in the broken pedal bin. ‘I don’t think James hit you,’ she said. ‘He’s been drumming nonstop. I was listening to him. I think you’re after attention again.’ Since Griff had gone to Scotland, Angharad had become abnormally clingy, unwilling to let her mother leave the room.

Siân opened the fridge door and glanced over the contents: Chantenay carrots and florets of broccoli stacked neatly in the glass vegetable box. There were six cans of Coca-Cola lined up on the top shelf, faces forward, a gap the width of a centimetre separating each. She placed the tip of her index finger into one of the lovely spaces and ran it along the edge of the cold aluminium. It gave her an immense sense of satisfaction, doing that, knowing something was in order. She had no control over the mountains of clutter in the rest of the house. However early she got up to polish and organize, Griff and the kids were always a step ahead of her; frenzied mounds of greying underwear on the bedroom floor, rowdy torrents of toys jumping out of their numerous toy-boxes. Secretly, she envied Rhiannon, who had lie-ins on Sundays and went for aromatherapy massages in white-walled beauty parlours. What it was, Siân had never had a massage, and God knows she deserved one.

There was half a bottle of Chardonnay next to the huge carton of skimmed milk, something Rhiannon had left behind. Rhiannon made a quick exit whenever the kids were about because Rhiannon hated kids. Siân poured some of the wine into a beaker and lifted it absently to her mouth. ‘Come in the living room with Mammy and Niall,’ she said, offering Angharad her spare hand.

Angharad leapt to catch it, springing over the tiles as though over some imagined jungle ravine. Siân stood in front of the mirror again and wiped her left eye clean. She reapplied the makeup, sweeping at her lashes with the mascara brush. She popped the top off a brand-new scarlet lipstick.

‘What are you doing, chick?’ Griff said. He was standing in the doorway, a black silhouette blocking the sunlight from the street. He came into the house, scratching his head with the stem of his van key.

Siân stood still, the red lipstick frozen in mid-air. She wasn’t sure how long he’d been there watching her. ‘I’m getting ready,’ she said, ‘for work,’ though she knew it was more than that. She’d woken in the morning with a sudden craving to look like a glamorous mother, like the ones she saw every day in the films. It was pressing on her like an iron. There was a time when every man in Aberalaw noticed her. At eighteen she could stroll across the square in a shift dress and a pair of slingbacks and the boys outside the Pump House turned to stone. Only their eyes moved, like the eyes in old oil paintings. Now she could probably run through the town in her nightdress and no one would bat an eyelid. She was 28, but she could have been 82. On her way home from the school she’d nipped into the chemist on the High Street and bought the lipstick. She nearly didn’t, because it cost four pounds, and a mouth her size needed a lot of lipstick, but the name of the shade was Desire, and that seemed right. ‘Did the van pass the MOT?’ she said. She ran the colour across her lips quickly, like a tick.

‘Yeah,’ he said, ‘just. I saw Marc in the garage. He was buying a tartan blanket. He said Rhiannon’s organizing a picnic on Saturday. He asked me if you’d bring a few things from the takeaway.’

Siân groaned. She’d be able to get some things, cold curry samosas and pancake rolls, but she’d need to buy the salad and bread rolls. She’d need to sterilize the plastic Tupperware too. ‘Like I haven’t got enough to do,’ she said.

Griff shrugged, paused, said, ‘You don’t usually dress up to go to work, do you?’ He picked Niall up and held him to his chest, breathing in the yeasty smell of his skin. Angharad slipped her hands around Griff’s waist, still vying for some affection. They were a tangle of different-sized limbs, three pairs of the same sea-green eyes, all staring at Siân. She wished the kids had inherited her complexion. They were all freckles and sunburn. In this weather she was always smearing their shoulders with tomato guts because she couldn’t afford factor fifteen lotion. They smelled like jars of chutney. She shrugged. ‘Just wanted to see what I looked like with lipstick on,’ she said.

‘You know what you look like with lipstick on,’ Griff said. He looked at the lipstick on her mouth and then the lipstick smudge on her glass. ‘Is that wine?’ he said.

Siân looked at the amber liquid in the glass. It looked like wine.

She knew it was wine but couldn’t actually remember pouring it. She ran her tongue around her mouth, tasting it for the first time. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘it’s wine.’

He put Niall on the settee and went into the kitchen, huffing as he brushed past Siân. She heard the breath of the kettle as he switched it on. She followed him and stood in the doorway, a deluge of contempt streaming through her waters as she watched him set two mugs on the counter and spoon instant coffee granules into them, the metal clattering against the china. Whilst attempting domestic chores, he made a lot of mess and a lot of noise, deliberately performing them badly in the hope she’d never ask him to do them again. James was still drumming. Siân whipped the plastic sticks from his hand, waved him into the living room, but he stayed where he was, sitting on the miniature stool, eyes vacant.

‘Did I say I wanted coffee?’ Siân said, surprised by her own insolence. Typically she would have drunk it, thankful he’d done something. But she was angry, in a way she’d never been before. She could feel it swimming around in the pit of her stomach, a fuming cloud of black. She picked a mug up and threw the granules in the sink.

‘What’s the matter with you?’ Griff said, gawping at her. ‘You don’t even like wine. Are you pregnant again?’

‘Iesu mawr!’ Siân said, which was Welsh for Jesus Christ. ‘All you had to say was that I looked nice. I’m not pregnant.’ There was a magnificent sense of relief in the words, and in her raised voice. She’d never heard herself shout so loudly. Nobody in the house had. It was magnificently still, the only sound Siân’s own harried breathing. She felt more of the boisterous disdain wedged in her throat, fighting its way out. Before she could stop herself, she cried, ‘I can’t be pregnant, can I? Because I was sterilized! Because you wouldn’t get a vasectomy!’

Now there really were no lies in her house. She’d kept it quiet for two years, because she knew it’d break Griff’s heart. He wanted as many children as possible; refused point-blank to get seen to, like a stubborn bull who thought his manhood was in his testicles. It was hard work looking after kids, looking after them properly. Two was enough for anyone and she hadn’t planned Niall. She fell pregnant again before she had chance to organize contraception after Angharad. She couldn’t cope with four, not with two jobs. She was already scuttling about like the beheaded hen she’d seen at her mamgu’s farm. Another baby would’ve killed her. So when they told her she was entitled to tubal ligation she signed their form of consent, out of worry, not spite. Still, the news hit him like an uppercut. He was silent, his hand trembling as he dropped sugar into his mug.

‘The doctors advised me to have it,’ she said, staring at the floor. ‘They said I couldn’t provide more than three children with all the financial and emotional support they’d need. I’m not Wonder Woman, am I?’ She took a deep breath, disappointed by the last statement because she wanted to be Wonder Woman. ‘Anyway, I don’t sit in those shops every night, getting ogled by alkies so that you can pay for MOTs and drive around Scotland sleeping with Scottish groupies. I do it for the kids we’ve got.’

‘Siân!’ Griff said. ‘That money is for us to go to London. It’s our big break. Besides,’ he glanced sideways at her, ‘if you don’t want to get looked at, why would you put all that muck on your face?’ He gave the kettle a smug grin, pleased with his snappy comeback.

‘Piss off,’ Siân said, bereft of a clever retort. She passed the drumsticks to James and he took them tentatively, his mouth a big O. She took her bag from the hook behind the door. ‘There’s curry in the pot,’ she said not looking at anyone. On her way out she swigged the last of the repellent wine. She dropped her new lipstick into her handbag.

11

At lunchtime on Saturday, Andy and Ellie were five miles west of Aberalaw, in Pontypridd, the local market town; one high street with a Boots and a Woollies where people from the valley went to buy luxury goods, birthday presents for fussy teenagers, leather shoes for court hearings. Every other week they came, to stare at things they couldn’t afford, to spend time. In Marks & Sparks Andy fingered the cuff of a suit jacket, stroking it like money. ‘I like this,’ he said. Before Ellie had chance to get near it, a middle-aged woman squeezed between them and joined him in his approval, squinting at the buttons over her half-moon spectacles, heaps of plastic bags hunched under her podgy arms. After a minute she seemed to remember that she had no need for a man’s suit. Perhaps her husband was dead.

Ellie looked at the jacket. As she did she realized why Andy’d been so eager to get to the men’s department, marching in military step towards the formal wear. He was looking for a wedding suit. ‘It’s OK,’ she said, dread gripping her by the buttocks. She moved away from him, along the aisle to look at the silver cuff links. They were all packaged in little blue velvet boxes, one pair fashioned on a spirit level with a bead of purple liquid that swam around inside the transparent vials. Ellie was drawn to sparkle. She liked new, shiny things. At university she’d collected stainless-steel colanders and woks and hung them on the kitchen racks in the St Jude’s student house. She liked the way they looked when they caught the morning sun from the patio. She never used them. She never cooked. Her housemates did, and when the utensils burned or grew dull, she threw them away and used her pitiful student loan to buy more, too lazy to set to work with a scouring pad.

‘What about this?’ he said. He was holding a black shirt with a beige tie knotted around its collar, the whole cellophane package pulled close to his proud chest, his pupils broad like a kid on its first ecstasy pill.

‘Beige?’ she said, wrinkling her nose. ‘I don’t think it’d complement my bridesmaids,’ though she had no idea what colour her bridesmaids were going to wear. At some point in her life she must have wanted a white satin gown, a pearl-encrusted headdress, a horse-drawn carriage, ice sculptures, cake-toppers, champagne fountains. Most little girls did. But not Ellie, not now; now when she saw a wedding car her instinct was to shout ‘Don’t do it’ at the bride. She’d recently seen an advert for perfume on Andy’s big television, a film of a woman sitting at her dressing table on the morning of her wedding day, then cut to the same woman strutting along a catwalk, one silk winkle-picker in front of the other, ear-splitting applause from the crowded auditorium. The voiceover said, ‘For the happiest day of her life’, or something equally fey. That’s all Ellie wanted: a big dress rehearsal. Her appetite for married life had fallen by the wayside; what she wanted was a life.

Outside it was hot, the street thick with the smell of sweat and anti-perspirant. Tarpaulin market stalls lined the road, the Asian traders standing behind clothes racks, arms folded, as adolescent girls jumbled through the stock, their mothers wincing at their choices. All around, shoppers reluctantly handed over dog-eared five-pound notes and walked away with gauzy blue plastic bags. Behind the traditional market, the booths of the French travelling bazaar wound around the corner into Taff Street, the vendors packing wine and olives in brown paper, the tricolour draped behind them, the lower half of the town immersed in the stench of Roquefort like bags of rotting rubbish.

Gangs of teenagers were skateboarding around the tax office, their wheels scraping on the concrete as Andy and Ellie walked back to the car park, cutting through the dilapidated precinct. ‘When my mother and father got married they had the reception in their own garden,’ Andy said. ‘They had to call my mother away from the oven to cut the cake!’

‘It’s two thousand and three, And!’ Ellie said. ‘And I’m not your mother. I can’t buy a metre of tulle from a fabric stall and conjure it into a veil. It doesn’t work like that. Weddings cost a fortune. We could do Route Sixty-six before we put a deposit down on a cold finger buffet. And who wants a cold finger buffet?’

Ynysangharad Park opened up in front of them, the music from the bandstand drifting over to Bridge Street. On summer Saturdays the council provided free entertainment. ‘Can’t we do that instead?’ she said. ‘Go travelling? That’s a commitment. It’s a bonding exercise.’

Andy wasn’t listening to her. He was pointing through the railings of the park, at a ginger-haired boy kicking a football against a tree trunk. ‘Look!’ he said, ‘it’s James.’ He started walking towards the boy, through the ornate park gate. ‘Griff must be here somewhere.’

They were all there, Griff and Siân, Marc and Rhiannon, Johnny and his girlfriend, on the bank in front of the stage, their bodies propped around a tartan blanket. Johnny was sitting cross-legged, at the edge of the gathering, his messy black ringlets hanging limp between his shoulder blades. His girlfriend was lying next to him, blonde hair fanned out on the ground. Ellie’s nerves began to ring, vibrating against her spinal cord; she wondered how he’d got there, without her knowing about it. She tried to swerve towards them, but Andy gripped her wrist, pulling her towards Marc and Rhiannon. She sat down next to her sister-in-law, said, ‘What are you doing here? I thought Saturday was your busiest day.’

‘Nah,’ Rhiannon said. She was wearing a stupid white rah-rah skirt, her hands slotted between her fleshy legs. ‘Din’t have much on. Kelly’s there. Best way to teach urgh is to chuck urgh in at the deep end. She don’t listen to a word I bloody say. I deserve some time off, anyway. It’s hard work running a top company, El. Not like workin’ for someone else.’ She grinned; bared the fleck of gold in her molar. It must have had something to do with her, this cosy little set-up. Ellie wanted to ask her outright what Johnny was doing here, but Rhiannon’s fat face would curdle as soon as Ellie uttered the first J. She had to wait for the mystery to unfurl of its own accord, or resort to listening to Dai Davies.

‘El?’ Marc said. He was holding a plastic bag open, presenting her with four cans of lager.

She took one. Andy shook his head, and then by thought association patted his jeans pocket to check his car keys were still there.

‘Have some food,’ Siân said, waving at the Tupperware boxes. There were salads and chicken kebabs, hot-dog sausages stuffed in fresh finger rolls, a bottle of mustard seed dressing fallen on to its side. Andy picked a salad bowl up and started gnawing at a slice of cucumber. ‘Been looking at some outfits for the wedding,’ he said as he chewed, a rivulet of juice dripping from his lips.

Ellie rolled her eyes. ‘It must have taken you ages to prepare this,’ she said, hoping Siân would reveal the origin of the picnic.

Siân shook her head. ‘Chan gave me the kebabs last night. I threw the rest of it together this morning.’ She packed some of the used Tupperware into a cooler bag, said, ‘So did you find anything you liked? There was a wedding at St Illtyd’s this morning. I saw it when I was leaving. What it was, the bride in cream, the women in coffee. What colour are you thinking about, El?’

‘Yeah, El,’ Rhiannon said, flipping on to her belly. She picked up one of James’s stray miniature cars and threw it into Siân’s cooler bag. ‘What colours are ewe ’aving? Tell Auntie Rhi. Bet ewer gonna do somethin’ really unconventional.’

‘No,’ Ellie said. She knew she should say something about shoes, rings, jewellery; something that sounded convincing. The last thing she wanted was to give Rhiannon the impression that she didn’t want to marry Andy. But she was aware of Johnny sitting mere feet away. Her nerves were still fluttering, cells colliding with one another, pushing microscopic waves of panic through her veins. ‘Ivory,’ she said, glancing at him. He wasn’t listening but she tried to change the subject anyway. She pointed at the stage, said, ‘Who’s this band, then?’

‘The Water Babies,’ Griff said. He opened a can, sending a spray of white foam across the grass. ‘They’re shit. Don’t know how they got this contract – probably related to someone from the council. Wait till the Peel session goes on air, El. Fuckin’ bunch of Muppets’ll be too shamed to show their faces.’ He twisted the metal tab from the can and flicked it at Andy.

‘Wanna get her off the pill now,’ he said, pointing at Ellie. ‘Wanna start as soon as you get hitched if you wanna catch up with us. Me ’n’ Siân are going for the soccer team.’ He looked at Siân but Siân was looking down at the blanket, her eyes fixed on a blue criss-cross in the tartan, her bitten fingers lodged in her mouth. Ellie noticed her lipstick: vermilion red; the colour of blood.

‘I’m sure she’s pregnant anyway,’ Griff said, ‘the way she keeps crying in front of films that ain’t sad.’ He spat a glob of lager on the ground. As he did, the atmosphere changed, the sun sliding behind a cloud.

Johnny stood up, his long, skinny frame stretching into the heavens. Everyone watched as he brushed grass blades from his clothes and stooped to offer his girlfriend his hand. She took it and straightened up, the grey T-shirt that had ridden up her flat torso falling down over her taut waist. For a second, Ellie had spied her belly button, big and hollow, wedged in the centre of a size eight stomach, the colour of an unripe peach. She looked down at her own pierced navel; flesh plump around the steel belly bar. She was a size twelve on a good day.

‘Sorry, everyone,’ the woman said, gesturing at the food. ‘Johnny wants chips so we’re just going for a walk into town. We won’t be long.’ Ellie felt her heart sink, her oesophagus constrict, like someone with a nut allergy who’d just swallowed a whole sugared almond.

Rhiannon sat up. ‘There’s a good fish shop on Taff Street,’ she said. ‘Does Clark’s pies an’ that. Want me to show ewe?’

The couple didn’t answer her. They were already on the path leading out of the park, walking shoulder to shoulder, their footsteps concurrent, like policemen searching for evidence. They were stick figures on the other side of the railings when Griff said, ‘Who does he think he is? Arrogant English bastard. There’s plenty of food here, but that ain’t good enough for him, is it?’

‘Fuckin’ ’ell, Griff,’ Marc said. He was inspecting an elongated mustard stain down the front of his Liverpool shirt. ‘It doesn’t cost anything to be friendly. We only invited ’em because they don’t know anyone else. They only just moved here for God’s sake. Have some tolerance, will you? We’ll keep a welcome an’ all that.’ He spat into his hand, massaged the saliva into his chest.

Ellie smiled slyly to herself. It was Marc who’d invited Johnny, ergo it was Rhiannon who’d invited Johnny. The cunning cow fancied him herself – that’s why she’d made such a hubbub about being in love with Marc. At the Pump House, when Ellie had asked for his name, Rhiannon knew what Ellie was thinking because she was thinking the same thing. Ellie stole a quick peep at her. She was turned towards the railings, looking at the park gate, a nervous hum skimming out of her curvilinear lips. She was waiting for him to come back.

Griff ripped a grass stalk out of a big clump growing next to him, threw the wheat-coloured seeds on the breeze. ‘You don’t know what it’s going to cost yet,’ he said. ‘He could be a fuckin’ yardie for all we know. Dai said—’

‘Yardies don’t come from Cornwall,’ Rhiannon said, cutting him off. She kicked him in the ribs, showing everyone her black lace M&S knickers. ‘Bloody thicko! ’Ey come from Jamaica.’ Griff stared at her for a moment, but said nothing. He turned to look at the stage.

The band had already finished. The only sound was of children splashing and screaming, the noises from the swimming pool reverberating across the park.

Exactly eight minutes later, eight minutes that seemed to go on for eight years, Johnny came back, creeping towards the gathering like an insect on its stick legs. The girlfriend sat next to Siân. Johnny sat next to Ellie, his thighs hitched up to his chest, a polystyrene tray balanced on his kneecaps. While he’d been gone, the fire in her nerves had waned, but the moment he sat down it instantly came roaring back. Her heart pumped so fast she was sure everyone could see it, pounding against her ribcage, pushing the material of her blouse out, then pulling it back in again. She held her breath and watched from the corner of her eye as he lifted the chips to his mouth and shoved them inside, one after the other, chewing them regimentally. He caught her eye and held the tray up, offering her one.

Ellie shook her head and turned away. There was an anti-war demonstration trampling along the path on the other side of the park, fifty-odd people holding handmade placards aloft. ‘No More Blood for Oil,’ one said. As long as she could feel his awesome gaze on her face, she kept her eyes fixed on the demo.

‘You ever heard of the petro-dollar?’ he said as he put the polystyrene tray down on the ground. Ellie shook her head again, colour rushing to her face. She was so tense her jaw had locked. She was incapable of speech.

‘The petro-dollar is the cause of this war,’ he said. ‘Oil from the OPEC countries is always paid for in American dollars, right? So if Japan needs oil it needs to get some Yankee dollar.’ Ellie couldn’t quite meet his stare. He was something to look at: run-of-the-mill face and infolded lips, but large iron-oxide-black eyes, darker than carbon. She couldn’t understand a word he was saying for being fixed by those strange eyes. She quickly swallowed the well of saliva building up in her mouth and it went down like double-edged razor blades. ‘So to get American dollars,’ he said, ‘Japan needs to sell goods to the American economy. Let’s say it sells them a Honda, right? The Federal Reserve prints dollars and gives them to Japan.’