Полная версия:

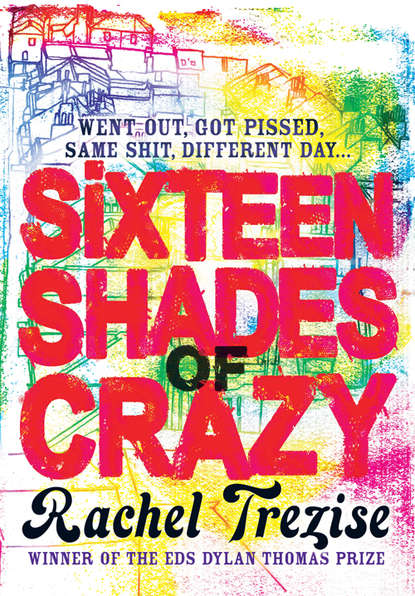

Sixteen Shades of Crazy

‘Now that I’m home,’ he said, pausing to ensure he’d got her attention, ‘we should fix a date for the wedding.’ He folded a piece of bread in half and mopped the egg yolk up from his plate.

Ellie put her own plate on the floor, setting her cutlery at the rim. It was eighteen months since he’d first asked. She was on her way home from work, stepping off the train in Aberalaw station when she noticed something strange about the mountain behind their house. Initially she thought it was a flock of sheep that had accidentally arranged itself into some uncanny correlation. When she got to the square she started to decipher the words. ‘MARRY ME ELIZABET,’ it said, vast characters spelt out against the moss green bracken with hundreds of smooth grey pebbles. Andy was standing on the doorstep, a nervous twist in his grin. ‘What do you think?’ he said, voice quivering. ‘I nicked them from Merthyr Mawr in the old man’s tipper. Weren’t enough to do the last H.’ She agreed, immediately, emphatically, because, even if she hadn’t wanted to marry him, she thought she would grow into wanting it, the way she’d grown into her sister’s hand-me-down clothes. Two days later, embarrassed by the attention it was attracting, she asked him to go back to the mountain and take the stones down. He’d bought her a nine-carat gold diamond solitaire, the only diamond she’d ever owned, and she’d spent days scraping her knuckle against the bay window, trying to slice the pane. The ring was dull now, with time and glue from the factory. They didn’t get married because they didn’t have the money to pay for the wedding. They still didn’t have the money.

‘My aunty’ll do the cake,’ Andy said, stretching to retrieve her plate, scraping the chips she’d left into his own dish.

‘Why don’t we go abroad?’ Ellie said. ‘Tobago or Cancún.’ It was the only way she’d escape interference from Andy’s relatives. There was a quagmire of customs to observe, a trail of conventional nonsense that kept all of their family traditions intact. Andy being her first son, Gwynnie demanded a church wedding. Ellie was petrified of walking into St Illtyd’s only to find the groom’s side bursting with jubilant spectators, her own pews entirely empty. She didn’t want to marry his family; she wanted Andy all to herself. ‘That’s what people do now,’ she said. ‘The bride and groom go away on their own. It’s more meaningful, don’t you think?’

‘We can’t do that,’ Andy said. ‘My mother and father could never afford the flight.’ He popped a chip into his mouth and sidled closer to Ellie, sliding across the settee.

‘What about a winter wedding?’ she said. It was August now. She was buying time, hoping she could change his mind, or that he’d forget about it all over again. ‘February. We could serve hot toddies instead of Cava. I could wear diamantés instead of pearls, a Cossack instead of a veil.’

‘The fourteenth?’ Andy said.

‘Valentine’s Day.’ Ellie sniggered. ‘That’s just tacky.’

‘It’s romantic.’ He clambered on to her body, bunching her wrists together, holding them like a bouquet above her head. Ellie bucked and screamed, the sharp screech breaking into peals of laughter. ‘Get off me,’ she said.

Andy kissed her, his keen tongue pushing into her mouth. After a moment, she started to kiss back hungrily, looking for something that had been there two years ago when they’d met, that had been there six days ago when he’d come back from Glasgow; something that wasn’t there now. All she could taste was the rust that had worked its way between them, months of widening water. His saliva was cold. An abrupt fatigue seeped through Ellie’s body. Her lips froze, her own tongue slumping back into her throat. As Andy pulled away she glimpsed the scar on his neck, four centimetres above his collarbone, a sunken white-blue tear shredding through his wheat-coloured skin.

‘What’s the matter?’ he said, voice doleful, eyes flickering in the last of the sunlight from the window.

‘Nothing,’ Ellie said. ‘Nothing.’ She waved his concern away with a chop of her hand, instructing him to continue. He began to work on her button fly. ‘Stop,’ she said pushing him away. She’d had an idea. She wriggled out of her jeans and then her pink cotton knickers, kicking them across the room. She flipped on to her naked belly and rose up on all fours. ‘I’ve been waiting for this,’ she said. It’s what she always said. Sometimes he beat her to it, and asked the question, especially if he was just home from tour. ‘Have you been waiting for this?’ he’d say. ‘I bet you have.’

She could feel him behind her, on his knees, the heat coming from him. She pressed her face against the arm of the settee, breathing the musty odour from the throw-over deep into her lungs, scrutinizing it for an iota of smoke, petrol; something that smelled like that man whose name was Johnny.

He placed his hand on her hip, getting closer.

‘I’ve been aching for this,’ she said.

6

Rhiannon weaved through the tables in the restaurant, winking at people she recognized. ‘Hiiiyyyaaaa,’ she said, wriggling out of her jacket. She sat down next to Gwynnie.

Gwynnie was a big woman with a permanent expression of terror splashed across her face. Nothing in her life had been easy and she expected her cycle of misfortune to persist until the death. Her skin was mottled with anxiety, her bones arthritic with exertion, her mouth quick with over-zealous counsel. Her demeanour was comical, her head constantly bobbing about in a frantic convulsion, gigantic sweat patches under her arms. Ellie often caught herself laughing at Gwynnie when she wasn’t trying to be funny. ‘We can order now,’ she said, waving at Andy’s father. ‘Where’s the waitress, Collin?’

‘Where’s the waitress, Collin?’ Collin said, mimicking his wife’s panicked voice. ‘How the bloody hell should I know, Gwyneth?’

Eating at the Bell & Cabbage was a relatively new experience for the Hughes family. Gwynnie used to cook Sunday dinner in her own kitchen; pork with roast parsnips and fresh vegetables served in her best bone-china tureens. Collin hurtled from the bedroom to the dining table in one fell swoop, his naked stomach riding out on the chair around him. Afterwards, Gwynnie did the washing-up, the pots falling from the draining board with a clang and echoing into the living room, like smites aimed at the girls’ sloth. ‘Shit!’ she’d say, sharp as a blade. At Easter the girls had booked a table for six in the carvery, encouraged by Gwynnie’s resentful sideways glances whenever they talked about steak they’d eaten at the Bell, or salads at fast-food joints. ‘There’s nice,’ she’d say, ‘there’s lovely,’ as if it was lobster bisque at The Dorchester. Her idea of a day out was a ramble through the car-boot sales in North Cornelly, spending her paltry income on labour-saving junk – old bread-makers and sandwich-toasters, stuff most people saw fit for landfill. When the day came, Collin sat in his reclining armchair, his hands crossed over his belly, as if trying to protect it from anything that wasn’t home-cooked. He refused to leave the house. Rhiannon managed to coax Gwynnie into her car, but at the restaurant she sat in the corner weeping, fretting over Collin’s non-attendance, the waitress staring as she set the gravy boat on the doily.

Collin turned up with the carrots, his comb-over hair blown out of place by the wind. He ate his food in obdurate silence, frowning over every mouthful, Rhiannon and Ellie secretly smirking at one another.

Marc put Rhiannon’s wineglass on the table now.

‘Is it clean?’ she said, twisting it in the light from the window. ‘There was some bugger else’s lipstick all over it last week.’ She was wearing a grey sweater with glittery pink writing across the bust. Her face was made up, her eyelids licked with bold blue eye-shadow.

‘Go down the club last night?’ Marc said, pushing the potatoes towards his father.

‘Aye,’ Collin said.

‘Artist any good, Gwyn?’ Rhiannon was playing with her peas, squashing them to a paste with the base of her fork, her wine held to her mouth, her voice echoing in the glass. Gwynnie quickly chewed a fatty morsel of beef, her head bobbling. ‘Two women,’ she said. ‘They were good but I think they were lezzers. They didn’t have no wedding rings.’

Collin stopped eating and glared at his wife. He commonly regarded women with a mixture of bafflement and trepidation. Ellie often caught him purposely avoiding eye contact, the way someone with a phobia of cats avoided a stray tabby. When he was sure she’d turned away, he’d peep furtively at her, as if ensuring she hadn’t moved any closer, or grown any bigger. He hated women. His only pleasure lay in trying to make their lives as miserable as his was.

For Ellie the feeling was mutual. She abhorred the control he had over Andy. He was absent for his childhood, locked in a prison cell for tax evasion. He missed his first word, his first footstep, and because he hadn’t witnessed these developments with his own eyes, he seemed to believe that they had never occurred. He treated Andy like a two-year-old, a fate Marc had somehow managed to avoid. He’d tell him to order the lamb instead of the beef, buy diesel-powered vehicles instead of petrol; put a patio in the garden instead of a lawn. When Andy and Ellie moved into Gwendolyn Street, Ellie asked Andy if they could go shopping for a couple of knick-knacks to make the place look like a home. Collin took it upon himself to play chaperone. Ellie’d been holding an Angelo Cavalli canvas, a beautiful black-and-white photograph of the Flatiron Building, when Collin swooped on her and plucked it out of her hands. ‘Ugly, isn’t it?’ he said, discarding it. ‘What about this?’ He passed her a Claude Monet print, Bridge over a Pool of Water Lilies. ‘Do you like that?’ he said. Ellie concurred, afraid of offending him. So he nodded and put it into their trolley.

When he was sure Gwynnie’d finished her sentence, Collin turned to look at Marc. ‘Heard about this new yobbo in town then, boy? I was talking to old Dai last night. Said he’s been hangin’ round the House, a scruffy lookin’ one.’

‘Are you talking about Johnny?’ Marc said.

A carrot split and fell from Ellie’s fork. It landed in the watery vegetarian gravy, driving a beige-coloured splatter across her plate. She kept her head down, eyes fixed on the food. The question mark lingered in the air of the restaurant for a time, utilizing her head as its period. She could feel the weight of Rhiannon’s stare.

‘I don’t know ’is name,’ Collin said. ‘Killed a fella, Dai said.’

‘Killed a fella!’ Marc laughed. ‘Honest Dad, you’re like a pair of washerwomen when you get together. Why do you think anyone who comes from somewhere else is a criminal? He can’t afford to live in Cornwall any more, that’s all. Tourists forcing the cost of living up.’

‘What’s his last name?’ Gwynnie said.

‘Frick,’ Rhiannon said, the word bursting proudly from her lips.

‘Frick?’ Gwynnie said. She shook her head, features quivering. ‘I don’t know of any Frick families round by here.’ Gwynnie knew everyone who lived in Aberalaw, all nine hundred and fifty-one of them. She’d lived there her entire life. She’d never dreamt of moving away from the street in which she grew up, or of doing anything more ambitious than raising her children to be honest and hard-working. She was the kind of woman who’d use the word ‘eccentric’ to describe anyone who’d read a book. But there was a fine line between naivety and ignorance. She’d called the Asian shopkeepers ‘a pair of suicide bombers’ when their grandson won the bonny baby competition in the local paper. Behind Rhiannon’s back, she called her ‘half a darky’.

Andy sighed, bored with the conversation. He obviously had no interest in Johnny. ‘I’ve got some news,’ he said squeezing Ellie’s knee. ‘Me ’n’ Ellie,’ he paused for a moment, deliberately duping Gwynnie into thinking that Ellie was pregnant.

Her mouth fell open; her head leant attentively to the side.

‘We’ve agreed on a date for the wedding, Valentine’s Day 2004.’

Gwynnie started rummaging around in her handbag, pulling out a crumpled tissue. Rhiannon slumped against the back of the bench and studied the fringes of the tablecloth, considering the implications. For a day at least she would not be the centre of attention.

‘When?’ Collin said.

‘February,’ Andy said. ‘February the fourteenth.’

‘Bloody strange time to get married – you should do it in October. A marriage licence is cheaper in October. That’s when me and your mother got married.’

‘Ellie wants a winter wedding,’ Andy said. ‘Don’t you, babe?’

Ellie wanted to plunge her knife under the table and puncture Andy’s hand. Everyone was gawping at her, waiting for her to start gibbering on about bridesmaids’ dresses and seating plans. Her muscles solidified, rooting her to the chair. Her cheeks glowed scarlet. ‘That’s okay isn’t it?’ she said. ‘A winter wedding?’ She smiled self-consciously, the skin of her lips cracking as they stretched across her teeth.

‘Your auntie Maggie’s away in her caravan in February,’ Gwynnie said. ‘I’d have to do the sandwiches on my own. And flowers! They’d be extortionate that time of year. Whenever the boys have bought flowers on Valentine’s Day—’

‘Mam!’ Marc said, scolding her.

Gwynnie stopped. She covered her mouth with her shrivelling fingers.

‘I don’t expect you to do all the food,’ Ellie said. She didn’t expect her to do any of it. ‘We’ll get caterers.’

‘But it’s tradition,’ Gwynnie said, starting again.

Rhiannon yawned loudly, half covered her mouth with her hand. She ran her forefinger along the rim of her empty wineglass, waiting for someone to notice her, lipstick still in place.

‘Are you going out somewhere today?’ Ellie said.

Rhiannon realized that her wish had been granted. She fluttered her eyelashes. ‘Out?’ she said.

‘Yeah, out,’ Ellie said. ‘Drinking. It’s just that you’ve got make-up on.’

7

After lunch, Ellie and Andy left Gwynnie and Collin in the carvery. They followed Rhiannon and Marc through the High Street, their bellies stuffed with profiteroles, an ice-cream van playing Für Elise. At the junction, Rhiannon pointed out her new range of professional styling products lined up on the salon windowsill. ‘Fifteen quid for the intensive light-reflecting conditioner, El,’ she said. ‘Only a two per cent mark up for ewe.’ It was the only window in the street not hidden behind a graffitied zinc shutter. Andy tried to catch Ellie’s hand but she brushed him off, reaching into her back pocket for a crumpled packet of ciggies. He watched her as she lit one, his mouth a single chisel-blow in pale flesh, clearly puzzled by her inclination to go out on a Sunday. Usually she sat in bed all afternoon, a magazine on her lap, a bar of chocolate on the bedside cabinet. Sometimes they had sex.

The Pump House picnic tables were set up around the mining statue. Griff was slouched behind a flat pint of lager and lime. Siân was sitting on the kerb, her orange ankle-length gypsy-skirt lying like a sheet over her legs, her hair scraped back from her face. She’d kicked her mules from her feet. One of them was on the pavement in front of the old YMCA, the fish-scale sequins sparkling in the sunlight. When Ellie’d moved to Aberalaw, Siân wore boob-tubes and hot-pants. With every new child, her tastes became more conservative: pastel blouses and woollen twinsets.

It was a shame to think of her smooth skin buried beneath several layers of cotton. A butterfly momentarily hovered at her throat and then danced into the ether, high above America Place.

America Place was a small street, a row of miniature fascias and hanging baskets erupting with tufts of orange pansies; a rare sight in a village marred by broken glass, concrete, used syringes, dog shit. The inhabitants had been having some sort of flower-growing competition for two years on the run. ‘Know why America Place is called America Place?’ Ellie said as she sat down on the kerb. Early in the nineteenth century, the whole street had decided to emigrate en masse. They’d appointed a chairman to book the tickets and collect the savings they’d accumulated over eight years. But he did a moonlight flit. The residents renamed the street, and called the old pub at the entrance to the estate the New York, New York. Siân knew the story. Ellie’d told her umpteen times, and on each occasion wondered why Siân didn’t find it as intriguing as she did. Ellie was besotted with anything to do with America.

‘Yeah, we all fuckin’ know,’ Rhiannon said. ‘Ewe never stop bloody tellin’ us, do ewe?’

‘Have you ever seen a film called In America?’ Siân said, spitting a chewed fingernail out of her mouth. ‘What it is, it’s about an Irish couple who go to New York with dreams of acting on Broadway, but end up in a stinking block of flats. Nobody’s taken it out yet.’ She worked in the video shop and watched each new release when it arrived, sitting at the counter with a packet of chocolate biscuits.

‘Have a good bloody look at it, El,’ Rhiannon said, ‘’cause it’s the closest to America ewe’ll ever get. Like them lot,’ she pointed at America Place. ‘Ewev’e already missed the fuckin’ boat.’

There was another thing that interested Ellie about America Place, something she never talked about: Andy’s ex-girlfriend, Dirtbox. She lived in one of the converted cottages but Ellie’d forgotten which. He’d taken her to a party there once, a few weeks into their courtship, before he’d admitted that Dirtbox was his ex-girlfriend. He introduced her as his ‘friend’, the clumsy air around the word divulging a sense of mischief Ellie couldn’t quite define. The three of them had stood in the kitchen, gazing at her potted herbs. Then Andy pointed through the French doors at the prize-winning Lionhead rabbits leaping around in their pen. ‘That’s Flossy,’ he said, ‘and the other one is Thumper. Shag like bunnies they do.’ Something in that sentence revealed the true nature of his and Dirtbox’s relationship. Ellie hadn’t imagined that Andy’d had a life before she’d arrived, and the realization had hit her like a juggernaut doing ninety. She’d immediately fled, the soles of her motorbike boots bouncing on the cracked pavements of America Place, then Dynevor Street, then the dogtooth tiles of the railway station. Andy’d followed, coins dropping out of his pockets and rolling down on to the track. As he’d reached her, the Ystradyfodwg train appeared, its brakes screeching. Andy fell at her feet, tears streaming down either side of his nose.

‘Don’t leave me,’ he said tugging at the hem of her gingham dress, like a bad actor in a cheap made-for-TV film.

The electronic doors parted with a computerized bleep.

Ellie prised his fingers from her skirt, one digit after the other.

‘I’ll kill myself if you go,’ he said, skin claret.

Ellie stepped on to the train. She didn’t go in for emotional blackmail then; that self-confident, post-Plymouth period of her life which felt like an aeon ago.

‘I’ll get the round in then, shall I?’ Andy said now, ambling into the pub.

Marc picked up a newspaper, opened it to a black-and-white photograph of George Bush. ‘US admit guerrilla warfare,’ the headline said. He quickly flipped the page to a large colour photograph of a topless blonde model with generous, upturned nipples.

Rhiannon sidled closer to Siân, brushing her plump fingers through her long ponytail. ‘Feels a bit dry, love,’ she said. ‘I’ve got some new conditioner. Why don’t ewe pop in the shop this week?’ Her voice the honeyed adaptation she used to flatter people she didn’t really like. Siân pulled her hair away from Rhiannon and smoothed it on to the opposite side of her neck.

Andy came out carrying drinks on an aluminium tray. ‘Dai just told me that Gemma Williams is up the duff,’ he said. ‘Williams the Milk’s daughter. She’s only fourteen.’

Rhiannon opened a compact and stared into the mirror. ‘Stupid likkle slut,’ she said, plucking a hair from her chin with a pair of steel tweezers.

‘Is there anybody else in there?’ Ellie said. She thought Johnny might have been here, smoking his abundant supply of cigarettes, buying beer for his girlfriend, telling the bar-staff that under no circumstances were they allowed to supply her with vodka. She thought he might have been coming here for weeks; that’s why she’d come.

‘No,’ Andy said. He shrugged. ‘Why?’

Ellie ignored him, glanced around the square. The pine trees on Pengoes Mountain stretched up behind the sagging rooftops of the terraces, their branches thick with foliage, their tips piercing a cornflower sky. A car thudded over the cattle-grid, the sound echoing across the valley.

Suddenly Ribs came out of the pub. ‘What the fuck are you doin’ yer?’ he said blinking at Andy. ‘Never see ’im on a Sunday do we?’ Ribs was a closet transvestite. He lived on his own in a house in Dynevor Street. He used to share a flat with Griff in the YMCA. Sometimes he forgot to remove his make-up before he left the house and he’d sit at the bar in the Pump House for two hours, a greasy film of red lipstick staining the rim of his pint glass, cheap blue mascara slithering down his cheekbones. There was some speculation about his sexual orientation because he’d tried to kiss Collin once, after a lock-in on a New Year’s Eve.

‘What songs shall we do, Ribs?’ Griff said, ‘for the John Peel session on the radio?’

Ribs was a big fan of The Boobs. He’d been around since Marc started the band at the age of sixteen, supported them through the garage days when they practised in an abandoned allotment behind the industrial estate. He still went to every local gig, but didn’t know one song from another. He stood in front of the stage, his mouth flapping open and closed like an atheist holding a hymn book at a funeral. He wiped a sheet of sweat from his forehead, a coat of peach-coloured foundation disappearing with it. ‘It’s nearly bank holiday again,’ he said. ‘What are you going as this year?’

Some of the villagers wore fancy dress for the annual August bank holiday pub crawl, because this was Aberalaw and they had to make their own fun. Ribs’s proudest moment came whilst wearing shocking pink stockings and red stilettos, pissing in a litter bin in the High Street, his back to the road. ‘Show us your tits, love,’ a bunch of joyriders had yelled at him through a car window.

‘I’m going as a copper,’ he said, ‘a female copper.’

Ellie was looking at America Place again, and remembering that her grandmother had had wild pansies growing in her front garden, an exquisite purple colour. She had a funny name for them. ‘Johnny Jump-Ups!’ she said, thinking aloud. ‘That’s what my nanna called pansies, Johnny Jump-Ups.’ There, she’d said it. It had been balancing on her lips for a week and now it had slipped out accidentally, like a burp.

‘That’s that English bloke’s name ini?’ Ribs said. ‘Johnny?’

‘He’s a drug dealer he is,’ Griff said. ‘Dai told me, fallen out of favour with some big shot up in England.’

‘Dai’s a prick,’ Marc said.

Ellie was thrilled with the response. If she couldn’t have Johnny there, the next best thing was listening to people talking about him.

She liked the idea of him being some sort of fugitive, escaping Cornwall under the cover of darkness, his passport wedged in his back pocket. That image turned her nipples hard.

Rhiannon snapped her compact shut. She looked at Ellie, brown eyes turning to brass. ‘Very funny, El,’ she said. ‘Johnny Jump-Ups? What did she call carnations?’

‘Carnations,’ Ellie said, playing ignorant, the familiar sting finding its way to the sides of her face. Rhiannon laughed her fat, fake laugh. She dropped her compact into her bag, fastened the zip and pushed the bag aside. ‘Why don’t ewe tell everyone ewer special news, then El?’ she said. She slowly eyed everyone at the table and then after a moment, said, ‘Ellie and Andy are getting married next year, Valentine’s Day. Ain’t that romantic?’

‘No way!’ Siân said, throwing herself at Ellie.