Полная версия:

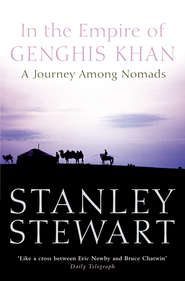

In the Empire of Genghis Khan: A Journey Among Nomads

I took the tram to Mother Russia. Her statue overlooks the Volga on the northern outskirts of the city. Long before I reached her, I could see her sword raised above a block of tenements. It vanished for a time then her vast head came floating into view beyond the smokestacks of a derelict factory. Her size confused my sense of distance and scale, and I got down from the tram three stops too soon.

Long slow steps climbed through a succession of stone terraces framed by stone reliefs of grieving citizens. On the last, where a granite soldier with a sub-machine-gun symbolizes the defence of the city, sounds of battle are piped between the trees and a remnant of ruined city wall. To one side stands a rotunda where 7200 names, picked at random from the lists of dead, are inscribed in gold on curving walls of red marble. A tape-loop plays Schumann’s Traümerei; the choice is meant to indicate that Russians held no grudge against ordinary Germans.

On the hill above, Mother Russia bestrides the sky. As tall as Nelson’s Column, and weighing 8000 tonnes, the statue depicts a young woman, a Russian version of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, striding into a new world, in too much of a hurry to notice she was still in her nightdress. Her upraised sword is the length of a tennis court. Her feet are the size of a London bus. She is striding eastward, across the Volga, glancing over her shoulder to check that Russia is following.

I reclined on her big toe, warm in the afternoon sun, and gazed across the Volga at an empty lion-coloured prairie beneath a fathomless sky. The city stretches for some 40 miles along the western bank without ever daring to cross the river, as if recognizing that the far bank was another country. There are no bridges. If the Black Sea was the nomadic frontier to the Greeks in antiquity, in modern times in Russia the focus for that uneasy boundary has been the Volga. Within its long embrace lies Mother Russia; beyond was the Wild East, the untamed land of the Tartars. Volgograd was founded in the sixteenth century as a fortress, built to protect Russians settlers from their nomadic incursions. If the Volga is the quintessential Russian river, it is due in part to its character as a frontier, poised between the national contradictions of West and East, of Slav and Tartar.

Scratch a Russian, the old proverb goes, and you will find a Tartar. Over the centuries the Mongol Golden Horde which dominated the Russian princes from their tented capitals here on the Volga became absorbed into Russia’s complex ethnicities. The Tatar Autonomous Region lies north along the Volga around its capital Kazan. The Kalmyks, a Mongolian people, have their own region to the south. The Cossacks, another Tartar band, are part of Russian folklore. In these parts every Russian town has its Tartar district where the lanes become narrower, the people louder and life less ordered. Beneath the feet of Mother Russia, brandishing her sword at the eastern steppes, is a Tartar tomb, the Mamaev Kurgan, centuries older than the city.

From Mother Russia’s big toe, one is reminded of the political context of the ambivalent relationship between Russian and Tartar. The statue striding towards the Volga is a symbol of the reverse of a historic tide. By the eighteenth century the balance of power had tilted irrevocably away from the peoples who had migrated from Central Asia and who had sapped Russia for centuries with their demands for tribute. By the age of Peter the Great, Russia was coming to dominate the nomadic hordes of the steppes, and had embarked upon an eastward expansion that would eventually reach even distant Mongolia. They built towns, roads, schools and factories; they sought to bring settled civilization to the regions beyond the Volga. Only by controlling these turbulent regions could they feel secure. Marching toward eastern horizons, the colossal statue seeks to mask the scale of Russian anxieties. Their imperial ambitions were a plea for order, for the safe predictability of sedentary life.

Friar William reached the Volga in the middle of August. The problem with his mission was that no one knew what to do with him. Mongol princes to whom he presented himself invariably resorted to handing him on to their superiors. In the Crimea he had been given an audience at the camp of the Mongol governor, Scacatai. When asked what message he brought to the Mongols William replied simply, ‘Words of Christian faith.’ The governor ‘remained silent, but wagged his head’, then said he had better speak to Sartaq, a senior figure, camped beyond the River Don.

While William waited on arrangements for his onward travel he had a brief breakthrough on the evangelical front when he persuaded a resident Muslim to convert to Christianity. Apparently the fellow was much taken with the idea of the cleansing of his sins and William’s promise of Resurrection from the Dead. The scheme came unstuck at the last moment however when the man insisted on first speaking to his wife who informed him that Christians were not allowed to drink koumiss, the fermented mare’s milk that is the chief tipple in nomad tents. In spite of William’s assurances that this was not the case, the fellow decided he wouldn’t risk it.

Sadly the belief, then current in the West, that Sartaq was a Christian turned out to be an ill-founded rumour. He was happy to receive gifts from Christian envoys, William reports on reaching his camp, but when the Muslims turned up with better gifts, they were immediately given precedence. ‘In fact,’ William confesses, ‘my impression is that he makes sport of Christians.’ Unsure how to deal with his visitors, Sartaq sent the friars on to his father, Batu, who was encamped on the Volga.

Batu was already migrating toward his winter pastures in the steppes to the east of the Volga, when the friars caught up with him. ‘I was struck with awe,’ William wrote on seeing his encampment. The vast sea of tents had ‘the appearance of a large city … with inhabitants scattered around in every direction for a distance of three or four leagues.’ At its heart stood the great pavilion of Batu, its tent flaps open to the sunny and auspicious south.

William’s first audience with Batu proved an interesting moment in east-west relations. When they were led inside the tent by their escort they found the grandson of Genghis Khan seated on a broad couch, inlaid with gold, amidst an assembly of attendants and wives. For a moment no one spoke. The friars stood, slightly intimidated by the grandeur of the pavilion, while the Mongols stared. Here were the envoys of the King of the Franks: two fat monks, barefoot, bareheaded, clothed in dusty robes. Itinerant peddlers would have presented a more respectable appearance.

William was not in the best of moods. This was his third Mongol audience in less than three months; each was as inconclusive as the one before. Further irritated by being obliged to kneel before Batu, he waded straight in with the hell and damnation. He would pray for his host, the friar said, but there was really little he could do for him. They were heathens, unbaptized in the Christian Church, and God would condemn them to everlasting fire.

When William had finished his introduction, you could presumably have heard a pin drop. At this point the friar carefully edits his own account and does not record Batu’s response. But the reply of the barbarian khan, the harbinger of chaos and darkness, has passed into folklore. We find it in the records of one Giacomo d’Iseo, another Franciscan, who relates the story of the encounter as described by the King of Armenia. It was a lesson to the westerners in a civilized discourse.

Surprised by William’s aggressive manner, Batu replied with a parable. ‘The nurse,’ he said, ‘begins first to let drops of milk fall into the infant’s mouth, so that the sweet taste may encourage the child to suck; only next does she offer him the nipple. Thus you should first persuade us in simple and reasonable fashion, as (your) teaching seems to us to be altogether foreign. Instead you threaten us at once with everlasting punishment.’ His words were greeted with a slow hand-clap by the assembled Mongols.

Despite Batu’s disapproval, he invited William to sit by him and served him with a bowl of mare’s milk. He wished the friars well and would be happy for them to remain in Mongol territories, he declared, but unfortunately he could not give them the necessary permissions. For this they would have to travel to the court of Mongke Khan, Lord of all the Mongols, who resided at the capital Qaraqorum in Mongolia itself, almost three thousand miles to the east. William’s journey had only just begun.

A month later a guide arrived to escort them eastward. He seemed a trifle tetchy about being assigned two fat foreigners, and was obviously worried that they would not be able to keep up. ‘It is a four months journey,’ the guide warned them. ‘The cold there is so intense that rocks and trees split apart with the frost … If you prove unable to bear it I will abandon you on the way.’

By day some life returned to the lobby of the Hotel Volgograd. The receptionist was awake and the ancient lift operator loitered by the door. All they lacked were guests.

The Intourist office located just off the lobby exuded the solid respectability and feminine good sense of a Women’s Institute, circa 1957. It was staffed by a phalanx of charming middle-aged matrons, dressed in twinsets and pearls. I dropped by in time for afternoon tea.

In the past most tourists to the city came from the former Communist countries of eastern Europe as well as from West Germany where former Panzer officers were curiously keen to revisit the scene of one of their more spectacular defeats. Few of the former could afford the trip now, and the latter were dying off. In the absence of other tourists, travel information had rather dried up. The planetarium, boat trips on the Volga, Kazakh visas, all were a mystery to the women of Intourist. I asked about train tickets; I had spent much of the morning in the railway station trying to purchase a ticket to Kazakhstan. Offering me a scone, Svetlana, the English speaker, admitted that train travel was beyond their remit. In the genteel atmosphere of the tourist office, beneath posters of Volgograd’s factories, my enquiries began to seem impolite, and the conversation turned to a series of Tchaikovsky concerts to which the office had subscribed.

Into this civilized circle Olga descended like a one-woman barbarian horde. I heard my name, a head-turning shriek from the lobby, and suddenly there she was pushing through the glass doors of the office and limping towards us, still in the heels and hooker’s uniform of the previous evening.

‘Master Stanley,’ she called, waving and smiling with the excitement of a fond reunion. Looking up from their tea, the Intourist women gazed at this advancing apparition with horror. Then, as one, they turned their shocked expressions to me. I felt myself blushing, compounding the impression of guilt. There was a moment of dreadful silence as the irrepressible Olga stood before us.

‘Hellooo,’ I said feebly.

‘Master Stanley, I am looking everywhere for you,’ Olga said. ‘You are not in your room.’

The wide eyes of the Intourist women narrowed as they swung back from my red face to a closer inspection, from the feet up, of Olga – the torn fishnets, the bulging figure in the cheap tight dress, the fat cleavage, the heavy erratic make-up. Then they turned their gaze to one another, a circle of smug disapproval framed by raised eyebrows and pursed lips.

Amidst their condescending censure some instinct for civility finally surfaced in me, and I rose to offer Olga my seat. She did not take it. A change in the set of her shoulders signalled her recognition of the women’s disdain.

In the lobby Olga said, ‘You want train tickets?’ The hotel grapevine had already informed her of my visit to the railway station.

‘I am trying to get a ticket on the Kazakhstan Express,’ I said.

‘I can get for you,’ she announced. ‘No problem. Don’t waste time with Intourist peoples.’ She made a face towards the glass doors. She didn’t seem to like the company I kept.

Volgograd was the unlikely setting for an international festival of contemporary dance which coincided with my visit, and in the evening I went along to a performance by the Be Van Vark Kollektivtanz from Berlin. The principal piece, Orgon II + III, was based on the work of Willem Reich, the Austrian psychoanalyst, whose guiding principle was that mental health depended upon the frequency of sexual congress. He went so far as to recommend the abolition of the nuclear family which he identified as a deterrent to regular orgasms.

The Berlin avant-garde held no surprises for me since the evening I had taken my mother to a performance of a Handel opera at the Riverside Studios in London. My mother was very fond of Handel and I had booked seats in the front row which at the Riverside meant that you were more or less part of the action. I had not registered that the visiting company came from the cutting edge of German performance art. It was Handel all right, but not as we knew it. When the cast fluttered onto the stage after a lilting overture I was startled to see that they wore nothing more than one or two strategic fig leaves. The performance was in the Reichian mode and for the next two hours and forty-three minutes, unrelieved by anything so old-fashioned as an interval, the cast members cavorted carnally and orgasmically in our laps. I remember it as one of the worst evenings of my life, and cursed myself for balking at the ticket prices at Covent Garden. My mother however was delighted, and never tired of telling people about the production. ‘Such energetic performances,’ she would say.

The soundtrack of Orgon II + III, so far as one could tell, was of frogs mating. The dance itself was a frenzied affair with some brilliant and very physical performances. The dancers kept their clothes on and the orgasms, if there were any, were difficult to distinguish from the triple pirouettes. The audience however seemed rather stunned. Presumably Orgon II + III was a bit much for people emerging from seventy years of social realism, when culture was devoted to happy peasants striding into a golden future of social justice, international peace and good harvests.

I walked back to the hotel through a park where orgasmically dysfunctional families were sharing ice-creams. Young people loitered around the ubiquitous kiosks which sold beer and snacks, and shoals of drunks floated between the park benches. Someone suggested after the war that the smouldering ruins of Stalingrad should be left as a monument to the defeat of Fascism. But Stalin understandably did not like the idea of his name being associated with a pile of rubble, so large sums were diverted to the city’s reconstruction. The results are pleasant if uninspiring. The town is given to wide avenues interrupted by parks and war memorials. There are red sandstone apartments with balustraded balconies, built in the fifties as a reconstruction of the past, which look like they will last for ever, and yellow concrete tenements with damp stains, built in the sixties as a vision of the future, which look like they might not see the weekend.

I went for dinner in the grandiose restaurant in the hotel. In Stalin’s day it had presumably hosted power lunches of the Party hierarchy. These days it is as spectacular and as empty as a mausoleum. I sat by a tall window overlooking the square. The service left plenty of time to admire the marble columns, the gilt chandeliers, the vast ornate mirrors, and the tables laid with silver and fine linen. The waiter appeared to be the lift operator’s elder brother. It took him five minutes to cross the vast hardwood floor with a glass of rust-coloured water on a silver tray. He was deaf and I had to write the order in large letters on a napkin. He scrutinized this for some time, then, turning away without a word, embarked on the long journey towards the kitchen.

I was savouring the pleasure of dining alone when Olga appeared from beyond a fat pillar and sank into the seat opposite.

‘I have ticket,’ she said, lifting the precious article from her bag. ‘You go Saratov on the morning train, then changing for Almaty train.’

I thanked her enthusiastically but she waved her hand.

‘I wish I was going with you,’ she said, propping her elbows on the table and searching her molars, with a toothpick, for some remnant of her dinner.

‘To Kazakhstan?’ I asked. It was not a destination beloved of many Russians.

‘To Saratov. My village is there. On the other side of the river.’

I had not thought of her as coming from elsewhere, especially a village. She seemed so ingrained in this city with its opportunities for compromise and anonymity.

‘What is it like, your village?’ I asked.

‘Krasivoje,’ she said. ‘Beautiful. The apple trees have the flowers now. There is the Volga. It is like a …’ she searched for the word, pointing at the ceiling.

‘A chandelier?’ I suggested.

She shook her head impatiently.

‘A tobacco-stained ceiling?’

She frowned. ‘No, no.’ She flipped her hand to indicate something further.

‘The sky? Ah-ha. Paradise.’

‘Like paradise,’ she said. Her face had softened. ‘My son is there, with his babushka.’

She looked at me and I realized I had been promoted. A son was not an admission for potential clients.

‘How old is he? I asked.

‘Eight,’ she said. ‘I send money. But I will not bring him to Volgograd. Never to this city.’ She shook her head emphatically as if it was the city and not the human heart that was responsible for her downfall.

The advance notices for the Kazakhstan Express had not been encouraging. Everything I had heard or read about this train described it as a nightmare. The Intourist women in the Hotel Volgograd politely changed the subject when I mentioned it. The guidebook to Russian railways pleaded with readers to avoid it altogether. Even Olga was uneasy about the Kazakhstan Express.

Prostitutes, pimps, drug-pushers and thieves were said to have all the best seats; the sixty-hour journey to Almaty was standing room only for those without underworld connections. The passengers were described as drunk and belligerent, and the conductors locked themselves in the guard vans to avoid the knife fights. Robbery apparently was more common than ticket collecting. Passengers, it was said, were regularly gassed in their sleep and stripped of their possessions. Reports of the Mongol hordes in thirteenth-century Europe could hardly compete with the reputation of the Kazakhstan Express.

Arriving from Moscow, the Kazakhstan Express crept into Saratov station a couple of hours late, a shabby exhausted-looking train with windows too grimy to allow any view of the interior. The reassuring women attendants of Russian trains clocked off at the end of their shift and were replaced by Kazakh conductors, short stocky men with tattoos and pencil moustaches.

First impressions were encouraging: I boarded and passed down the corridor without a single confrontation with a knife-wielding thug. Predictably my bunk was already occupied by someone else who had paid a bribe to the conductor but after some negotiation I managed to secure a place in another compartment at the end of the carriage. It had the air of a bordello. Scarves had been hung over the windows flooding the place with a subdued reddish light. Women’s undergarments were strewn about like decoration. There was a heavy odour of cheap scent and the table was crowded with hairpins, combs, make-up, cigarettes and two empty bottles of Georgian wine. Amidst the debris three women lay on the bunks, slumbering odalisques, snoring gently in the sprawling postures of sleep.

I climbed onto one of the upper bunks and set about secreting my valuables about my person. The limited banking facilities on the journey ahead meant that I was carrying bundles of cash. I lashed thick wedges of roubles around my midriff and filled my boxer shorts with American dollars. The reputation of the train and the atmosphere of the compartment reminded me of a story that I had heard recently about the Trans-Siberian Express. A friend had been obliged to share his compartment with a demure-looking woman who was a librarian by day and a hooker by night. From Moscow to Vladivostok, she had entertained a succession of clients on the upper bunk. I peered over the edge of my bunk at my travelling companions. With their scarlet lipstick and false eyelashes, they had obviously dispensed with the librarian disguise. I wondered briefly if Russia was turning me into a deranged puritan, seeing debauchery at every turn.

We rattled across the Volga and rode away into the late afternoon through an endless plain of wild flowers. Lines of telegraph poles shrank to nothing where dirt roads tipped over the edge of the flat horizons. Villages marooned in all this space were shambolic entities. Everything looked home-made. The houses were made from scavenged planks while the tractors appeared to be assembled from wheelbarrows and old sewing machines. A town hove into view, announced by box cars and grain silos. Ancient cars lumbered through its streets, raising slow clouds of dust between concrete tenements and vacant lots. A row of smashed street lamps dangled entrails of loose wires. In these regions public utilities had a short life. Drunks used street lamps for target practice, and young entrepreneurs stole the glass and the bulbs for the black market. Then we were in the country again, turning through bedraggled meadows where brown and white cows lifted their sad heads as the train passed.

The women awoke together at six o’clock as if a bell had rung. Nodding in my direction, they lit cigarettes and set about filing their nails. Precedence among them was denoted by the number of their gold teeth. I wondered if it was the reputation of the train which had persuaded them to deposit their savings in dentistry. The eldest, a butch blonde, had a mouthful while the youngest, a pretty woman in satin trousers and sunglasses, relied on a single gold incisor to ensure her financial security. They settled down to read the Russian tabloids. Devoted to everyday tales of corruption, sex and violence, the gory covers displayed montages of corpses, American dollars, blazing guns, and a man with tattoos thumping a half-naked woman. I glanced over one of their shoulders at an inside page dominated by a photograph of a man’s naked bottom with a spear planted deep in the right buttock. Mercifully this was in blurry black and white.

With evening the Kazakhstan Express settled into a swaying domesticity, the antithesis of the dark criminality that the train was rumoured to represent. Up and down our carriage the compartments had been colonized by their passengers. Bags were unpacked, blankets unrolled, shoes stowed beneath the seats, and food, newspapers and general clutter spread over the tables and the seats. The handrail in the corridor had been commandeered as a communal clothes line for towels and flannels. People changed into slippers and old sweaters, lit pipes and opened brown bottles of beer. Reclining on the lower bunks, unbuttoned and unconcerned, they might have been installed on familiar divans in their own homes. An old-fashioned neighbourliness took hold of the carriage with people popping in and out of one another’s compartments to share stories and sausages, or standing outside in the passageway like villagers at their front gates, gossiping, admiring the view, sharing cups of tea from the samovar.

Reports of barbarism invariably tend to exaggeration. The evil reputation of the Kazakhstan Express dated from the dark years of 1992 and 1993 when crime in the former Soviet Union surged into the vacuum created by the collapse of government authority. But a railway police force and the stubborn resistance of the ordinary passengers, who had set upon thieves like lynch mobs, had brought an end to this lawless period. Though it still has its problems, I can report that the Kazakhstan Express was a good train of decent people. The three women in my compartment were not prostitutes but traders transporting dresses to Almaty. In the evening they arranged a small fashion show for our immediate neighbours who applauded the latest Moscow fashions with innocent enthusiasm.