Полная версия:

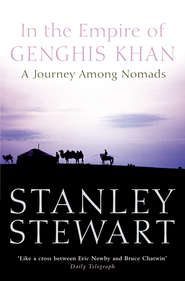

In the Empire of Genghis Khan: A Journey Among Nomads

I looked round at Kolya. The boy was pointing his gun at the singer. He swore at him, under his breath, as if he was speaking to himself.

‘Put the gun down, Kolya,’ I said.

He did not respond. For what seemed like long minutes no one moved. We were transfixed by the gun.

‘Put it down, Kolya.’ I forced myself to stand up. Kolya’s gaze flickered toward me for a second then returned to Rasputin. His face was flushed. I felt my heart pounding and my legs felt watery. I stepped between the two.

‘Get out,’ I said to Rasputin.

The singer seemed about to protest, but Anna silenced him. She stood up and pulled his arm. I herded them out of the door then closed it after them.

Kolya had lowered the gun. He picked at the barrel absentmindedly, childishly, with his middle finger. He pursed his lips, affecting a casual expression, as if the sudden terror that still stiffened the air in the room had nothing to do with him.

‘You’re an idiot,’ I told him. I wanted to shout at him; my own tension needed an outlet. He sat chewing his lip, gazing at the floor, then threw the gun on his bunk.

‘You’ll have to get rid of it,’ I told him. He said nothing. ‘The singer will tell the Ukrainian customs about the gun. They will search you. He might even be telling the captain now. You need to get rid of it. Immediately.’

He sat staring at the floor. Then with the surly grace of a child who had been ordered to clean his room, he picked up the gun, opened the porthole and dropped it into the sea. Then he lay down on his bunk and sobbed into his pillow.

Perched on the southern shores of the old Soviet Union, Sevastopol was a window on more tolerant worlds. There is a Mediterranean feel about the place, some tang of the south, some promise of escape, a lightness borne on the sea air and reflected in the pinkish hue of the stone façades. Built by Black Sea traders who had seen Naples, it has touches of architectural grandeur and a southern desire for colour. Side streets were full of flower boxes and haughty cats. Flights of stone steps connected avenues of plane trees and trolley buses. Vines trailed between the mulberry trees in walled gardens. In the midday sun cafés spilled onto the pavements, and people grew animated and gregarious.

It is easy to understand why the Crimea was the envy of the rest of the Soviet Union. Dour people from Moscow used to come to Sevastopol and Odessa just to look at the vegetables. In those days the Politburo holidayed on the Black Sea. In this easy southern climate it was a simple matter to believe that things were going well. Every other year the first families of the East, leaving their overcoats and their worries at home, gathered at a resort near Yalta just along the coast – the Brezhnevs, the Honeckers, the Zhivkovs, the Ceausescus, and the Tsendbals – to compare growth rates and grandchildren.

Though virtually unknown outside his own country, Tsendbal’s survival eclipsed them all. For forty-four years, as general secretary and then president, this obscure figure ruled the People’s Republic of Mongolia, the world’s second Communist state and the oldest of Russia’s allies. To keep tabs on him, the KGB had managed to marry him off to one of their agents, the boorish Filatova, a Russian from Soviet Central Asia. The Crimea was one of her passions and the Tsendbals came to the Black Sea at least twice a year. If any folk memories of the Mongol Hordes lurked in the Crimean subconscious, Tsendbal must have confused them. The heir to Genghis Khan was a small mousy man, the epitome of the faceless bureaucrat, obsequious to his domineering wife and his masters in the Kremlin.

In the afternoon I wandered through the park where Crimean War monuments were deployed between the flower beds. Todleben, who organized the defence of Sevastopol in 1855, towered serenely over strolling naval cadets in hats so ridiculous they might have been dressed for a children’s party. At the far end of the park a fat man reading a newspaper sold me a ticket for an empty Ferris wheel.

Ten years ago Sevastopol was the most closed of the Soviet Union’s closed cities, and spies in every Western nation would have considered a ride on this Ferris wheel as the pinnacle of their careers. Now the operator hardly cared enough about the presence of the former enemy to look up from the sports pages. With a series of creaking shudders I rose above the city. Beneath me, in the long protected harbour, lay the great Black Sea Fleet. It looked like a vast naval scrap yard full of rusting hulks. Economic collapse appeared to have done for the fleet what the naval strategies of Nato failed to do – keep much of it in harbour. Russia and the Ukraine had argued over the disposition of the ships when the latter declared its independence, though neither of them can afford to maintain its share of the naval loot.

Back at my hotel the lobby was dominated by a flashing sign that read El Dorado. Beneath it a cabal of young venture capitalists in baseball caps worked the slot machines. Upstairs in my room the television offered two Russian channels. On the first, old Russia survived. Rectangular men in grey suits were making interminable speeches. On the other channel, new Russia was in full cry. Encouraged by a deranged game-show host, housewives were performing a striptease. The applause levels of the audience determined which one would win the kind of washing machine I remember my mother throwing out in the 1960s. It was not difficult to guess which channel was winning the ratings war.

The finest part of Sevastopol is the esplanade along the seafront which stages the evening passeggiata. A series of neo-classical buildings – naval academies, customs houses, municipal offices – lines the long promenade where the inhabitants stroll arm in arm taking the sea air as swallows dive between the rooftops. Like the promenaders most of the buildings appeared to have lost the security of state employment and now struggle to make ends meet. Corner rooms in the old academies have been rented out as bars and restaurants. As the soft southern night fell, noisy discos mushroomed between the Corinthian columns where visiting leaders, including the Tsendbals of Outer Mongolia, once reviewed the naval fleet that was the pride of the Soviet Union.

At this season the Crimea was full of poppies. In the winding defile that climbed towards the interior, the kind of treacherous geography that betrayed the Light Brigade, poppies wreathed the outcrops of pink rock. Above on the plateau, ramparts of poppies enclosed fields where armies of stout women were cutting hay with scythes. Then the bus passed into a country of orchards where poppies trickled down the aisles between the trees to gather in pools among apple-green shadows.

I felt relieved to be on the move, to be consuming landscapes. The boat and its complex relationships had engendered a sense of confinement, some cloying and unsuitable feeling of responsibility. Now I was performing the traveller’s trick, the trick of departure, the vanishing act that marks the stages of a journey. For the traveller every encounter is conditioned by departure, by the impending schedule of trains, by the tickets already folded in his pocket, by the promise of new pastures. Departure is the constraint and the liberation of journeys.

On this bright morning fresh landscapes opened in front of me. Gazing out the window of the bus I delighted in the flash of fields and houses, the blur of poppies. I watched whole towns sweep past, adrift among wheat fields, then fall rapidly astern. At Simferopol I would get the train and tomorrow evening I would be on the Volga, seven hundred miles to the east. I felt the elation of movement. On this bus fleeing eastward, I felt I was staging my own disappearance, vanishing into Asia, leaving only a handwritten sign on the window of my former life: ‘Gone to Outer Mongolia, please cancel the papers’.

Since the time of the Scythians, the pastures of the Crimean interior had lured successive waves of Asian nomads onto the peninsula from the southern Russian steppes. When the Mongols arrived here in the thirteenth century it became an important component of the western province of the Mongolian Empire known as the Golden Horde whose capital lay at Sarai on the Volga. The Russians mistakenly called these eastern invaders Tatars, one of the many tribes that had been subdued by Genghis Khan in the early years of conquest, and the name stuck. In the west this became Tartar when Louis IX, William’s benefactor, transformed it by way of a Latin pun on ex tartarus, meaning ‘from the regions of hell’ recorded in classical legend.

Friar William landed at Sudak on the southern shore of the Crimea on 21 May, 1253. His plan was to visit a Mongol prince, Sartaq, rumoured to be a Christian, whose camp lay three days’ ride beyond the River Don. On the advice of the Greek merchants in Sudak he opted to travel by cart, filling one with ‘fruits, muscatel wine and dry biscuits’ as gifts for the Mongol officials that they would encounter along the way. He set off with four companions: his colleague, Friar Bartholomew, a man whose age and bulk made him even less suited to this epic journey than William himself; Gosset, ‘a bearer’; Homo Dei, a Syrian interpreter whose knowledge of any useful language was fairly shaky; and Nicholas, a slave boy that William had rescued in Constantinople.

But William’s journey was to take him a good deal further than he had planned. He was embarking on an odyssey that would lead him eventually to the distant Mongol capital of Qaraqorum, at the other end of Asia, well over four thousand miles away. If he had hoped to be back with his fellow monks in time for Christmas, he was to be disappointed.

At Simferopol I found the train to Volgograd guarded by an army of formidable carriage attendants, big-breasted women who stood by the doors like bouncers. They had beehive hairdos, thick necks and the kind of shoulders born of a career spent wrestling baggage and the heavy windows of Russian trains. Even their make-up was intimidating – scarlet lipstick, blue eyelids, raspberry-rouged cheeks, and malevolent bits of mascara gathered at the corners of their eyes. But once the train started, they underwent a transformation, from security guards to matrons. They abandoned their jackboots for carpet slippers, and began to fuss with the curtains. Taking pity on a hapless foreigner, my carriage attendant brought me a mug of tea from her samovar and I spread out a picnic of bananas, smoked cheese, a sausage, and Ukrainian pastries.

I shared my compartment with a burly Russian with mechanic’s hands and a simian haircut growing low on his forehead. He lay down on the bunk opposite and was asleep before we cleared the industrial suburbs of Simferopol. He slept with one eye slightly ajar. From beneath its lowered lid it followed me round the compartment. As he fell deeper into his slumbers his limbs began to convulse, like a dog dreaming of chasing rabbits.

On the edges of the Azov Sea we crossed out of Crimea on a littoral of islands. For a time the world was poised uneasily between land, water and sky. Causeways linked narrow tongues of marsh where lone houses stood silhouetted against uncertain horizons. A fisherman passed in a boat no bigger than a bathtub, his head bowed over nets, like a man at prayer. Watery planes tapered beneath landscapes of cloud until the sea and the sky began to merge, the same placid grey, the same boundless horizontals.

Beyond Melitopol we sailed over prairies tilting beneath towering skies. This was nomad country, the Don steppe, traversed by winds blowing out of the heart of Asia. The first Greek traders who ventured across the Black Sea were alarmed to find themselves here on the edge of another sea running north and east on waves of grass. The southern reaches of grasslands that stretch intermittently from Hungary to Manchuria, these prairies lent themselves for millennia to a culture of movement.

Maritime metaphors adhere to these landscapes with the tenacity of barnacles. Chekov grew up at Taganrog east of here along the shores of the Sea of Azov. He remembered as a boy lying among sacks of wheat in the back of an oxcart sailing slowly across the great ocean of the steppe. William wrote in a similar vein. ‘When … we finally came across some people,’ he wrote, ‘we rejoiced like shipwrecked sailors coming into harbour.’ Pastoralism survived on these prairies until the beginning of the twentieth century when the fatal combination of the modern age and Communism brought the world of the Scythians to a close. The tents and the horses retreated as lumbering tractors ploughed up the grasslands for wheat, and the prairie was colonized by villages and farmers.

The afternoon was full of country stations and haycocks. Peasant women lined the platforms with metal buckets of fat red cherries which they sold by the bowlful to the passengers through the windows of the train. As we pulled away they slung their buckets on the handlebars of old bicycles and diminished down dirt roads between flat fields of cabbages and banks of cream-coloured blossoms. Pegged like an unruly sheet by a line of telegraph poles, the prairie flapped away into unfathomable distances.

In the early evening I stood in the corridor at an open window, breathing in the country air as we passed through invisible chambers of scent: cut hay, strawberries, wet stagnant ditches, newly-turned earth, wood smoke. In a blue twilight we came to the estuary of the Dneiper, as dark as steel and as wide as a lake. Trails of mist unravelled across its polished surface. Dim yellow lights marked another horizon. It was impossible to tell if they were houses or ships.

All that remains of the great nomadic cultures that once roamed these regions are the tombs of their ancestors. William describes the landscape as being composed of three elements: heaven, earth and tombs. Scythians tombs, known as kurgans, litter these steppes like humpbacked whales riding seas of wheat. Beneath great mounds of stone and earth their chiefs were buried with their horses and their gold, their servants and their wives. The tombs were the only permanent habitation they ever built. Grave robbers have plundered the tall barrows for centuries, carrying off the spectacular loot of Scythian gold – ornaments, jewellery, weapons, horse trappings, all decorated in an ‘animal style’ with parades of ibex and stags, eagles and griffons, lions and serpents. But it was horses not gold that were the most compelling feature of these burials.

Horses attain a mythical status in nomadic cultures, and have always been crucial to their burials and their notions of immortality. Sacrificed at the funerary rites, they joined their masters in order to carry them to the next world. In a famous passage Herodotus described the mounted attendants placed round the Scythian tomb chambers. An entire cavalry of horses and riders had been strangled, disembowelled, stuffed with straw and impaled upon poles in an enclosing circle ready to accompany the dead king on his last ride. For centuries it was treated as just another of Herodotus’ tall tales until the Russian archaeologist N.I. Veselovsky opened the Ulskii mound in the nineteenth century and found the remains of three hundred and sixty horses tethered on stakes in a ring about the mound, their hooves pawing the air in flight.

The nomadic association of horses with immortality had even reached China, beyond the eastern shores of the grass sea, as early as the second century BC. In the mind of the Chinese emperor Wu-ti, military humiliations at the hands of the Xiongnu, the Huns of Western records, and fears about his own immortality had become strangely entwined. He seemed to embrace the convictions of the nomads who threatened his frontiers. From behind the claustrophobic walls of imperial China, he envied them their sudden arrivals, their fleet departures. Their horses, he believed, would be his salvation, and he set his heart on acquiring the fabled steeds of far-off Fergana in Central Asia. Known to the Chinese as the Heavenly Horses, they were said to sweat blood and to be able to carry their riders into the celestial arms of their ancestors.

Throughout his reign, Wu-ti lavished enormous expense and countless lives on expeditions to bring thirty breeding pairs of these divine steeds home to China. Only when they finally arrived was he at peace. He watched them from the windows of his palace like a smitten lover, tall beautiful horses grazing on pastures of alfalfa, their flanks shining, their fine heads lifting in unison to scent the air. ‘They will draw me up’, he wrote in a poem, ‘and carry me to the Holy Mountain. (On their backs) I shall reach the Jade Terrace.’

Chapter Three THE KAZAKHSTAN EXPRESS

In Volgograd the lobby of the hotel was steeped in gloom. A clock ticked somewhere. Blades of blue light from the street lamps outside cut across the Caucasian carpets and struck the faces of the marble pillars. A grand staircase ascended into vaults of darkness. In the square a car passed and the sweep of headlamps illuminated statues of naked figures like startled guests caught unawares between the old sofas and the potted palms. It was only ten o’clock in the evening, but the hotel was so quiet it might have been abandoned.

When I rang the bell at the reception desk, a woman I had not seen lifted her head. She had been asleep. A mark creased her cheek where it had been pressed against a ledger. She gazed at me in silence for a long moment as she disentangled herself from her dreams.

‘Passport?’ she whispered hoarsely, as if that might hold a useful clue to where she was.

My room was on the fifth floor. I was struggling with the gates of the antique lift when an ancient attendant appeared silently from a side doorway. He wore a pair of enormous carpet slippers and a silk scarf which bound his trousers like a belt. From a vast bunch of keys, he unlocked the lift and together we rose through the empty hotel, to the slow clicking of wheels and pulleys, arriving on the fifth floor with a series of violent shudders. When I stepped out into a dark hall, the gates of the lift clanged behind me, and the ghoulish operator floated slowly downwards again in a tiny halo of light, past my feet and out of sight. I stood for a moment listening to the sighs and creaks and mysterious exhalations of the hotel, and wondered if I was the only guest.

My room had once been grand. You could have ridden a horse through the doorway. The ceiling mouldings, twenty feet above my head, were weighted with baroque swags of fruit. The plumbing was baronial. The furnishings, however, appeared to have come from a car-boot sale in Minsk. There was a Formica coffee table with a broken leg and a chest of drawers painted in khaki camouflage. The bed was made of chipboard and chintz; when I sat tentatively on the edge, it swayed alarmingly. A vast refrigerator, standing between the windows, roared like an aeroplane waiting for takeoff.

I was tired, and in want of a bath. There appeared to be no plug but by some miracle of lateral thinking I discovered that the metal weight attached to the room key doubled as the bath plug. As I turned on the water, there was a loud knock at the door.

Outside in the passage stood a stout woman in a low-cut dress, a pair of fishnet stockings, and a tall precarious hairdo. But for her apparel she might have been one of those Russian tractor drivers of the 1960s, a heroine of the collective farm, muscular, square-jawed, willing to lay down her life for a good harvest. In her hand, where one might have expected a spanner, she carried only a dainty white handbag.

She smiled. Her teeth were smeared with lipstick.

‘You want massage?’ she said in English. ‘Sex? Very good.’

Prostitution is the only room service that most Russian hotels provide, and the speed with which it arrives at your door, unsolicited, is startling in a nation where so many essential services involve queuing. There was some lesson here about market forces.

The woman smiled and nodded. I smiled back and shook my head.

‘No thank you,’ I said.

But Olga didn’t get where she was by taking no for an answer. ‘Massage very good. I come back later. I bring other girls.’ She was taking a mobile telephone out of her bag. ‘What you want? Blondes? I have very nice blondes. How many blondes you want?’ She had begun to dial a number, presumably the Blonde Hot Line. I had a vision of fair-haired tractor drivers marching towards us from the four corners of Volgograd.

‘No, no,’ I said. ‘No, thank you. No massage. No sex. No blondes.’

I was closing the door. The woman’s bright commercial manner had slipped like a bad wig. In the gloom of the passage she suddenly looked old and defeated. I felt sorry for her, and for Russia, reduced to selling blondes to cash-rich foreigners.

‘Good luck,’ I said. ‘I hope you find someone else to massage.’

‘Old soldiers.’ She shrugged. ‘Only war veterans come here. It’s not good for business. They are too old for blondes. And they are always with the wives.’

I commiserated with her about this unseemly outbreak of marital fidelity.

‘Where you from?’ she asked. She brightened at the mention of London.

‘Charles Dickens,’ she cried. Her face suddenly shed years. Dickens, with his portrayals of London’s poor, had been a part of every child’s education in Russia under the old regime. ‘David Copperfield. Oliver Twiski, Nikolai Nickelovitch. I am in love with Charles Dickens. Do you know Malinki Nell. Ooooh. So sad.’

Suddenly I heard the sound of the bath-water. I rushed into the bathroom and closed the taps just as the water was reaching the rim.

‘What is your name?’ Olga was inside the vestibule. She seemed disappointed with an unDickensian Stanley. ‘You should be David. David Copperfield. In Russia they make a film of David Copperfield. He look like you. Tall, a little hungry, and the same trouble with the hair.’

‘What’s wrong with my hair?’ I asked.

‘No. Very nice hair. But you should comb.’ She was looking over my shoulder at the room. ‘They give you room with no balcony. Next door, the same price, a better room with balcony. They are lazy. Hotel is empty. What does it matter?’

When I turned to glance at the room myself, she teetered past me on her high heels and sat on the only chair. She seemed relieved to have the weight off her feet.

I stood in the doorway for a moment then decided I didn’t have the heart to throw her out. Dickens had already made us comrades.

‘Have a glass of vodka,’ I said.

I unpacked my food from the train and she took charge of it, pushing aside my Swiss army knife and fetching a switchblade out of her bag. She kicked off her shoes and carved the sausage, the dark bread, and the cheese, peeled the oranges and the hard-boiled eggs and poured out two small glasses of vodka.

We talked about Dickens and Russia. For seventy years Russians had read Dickens as a portrait of the evils of Western capitalism. Now that they had capitalism themselves, the kind of raw nineteenth-century capitalism that the revolution had interrupted, Dickens had come to Russia. The country was awash with urchins, impostors, fast-talking charlatans, scar-faced criminals, rapacious lawyers, deaf judges, browbeaten clerks, ageing prostitutes, impoverished kind-hearted gentility, people with no past, and people with too much past.

‘Russia is a broken country,’ Olga sighed, failing to see the Dickensian ingredients of a sprawling Victorian pot-boiler all about her.

Her mobile rang. She grunted into the mouthpiece a few times then put it away again. ‘Business,’ she said, squeezing her feet back into her scuffed stilettos. She begin to pack up our picnic.

‘Don’t leave the cheese out,’ she said.

She let out a long sigh as she hoisted herself to her feet. ‘I am tired,’ she said, straightening her dress.

‘Goodbye Master Stanley. If there is something you are needing, you see me okay. Ask at reception. They all know me.’

Then she teetered away up the hall into the dark recesses of the hotel.

Russia’s tragedies are on a different scale from other nations’, as if disaster has found room to expand in its vast distances. Of total losses in World War Two, some fifty million people, over half were Russians. One sixth of the population are said to have perished in what Russians call the Great Patriotic War. Volgograd, under its old name of Stalingrad, was the scene of one of the most horrific battles. In 1942 the German Sixth Army laid siege to the city for four months, bombarding it relentlessly, reducing the city to rubble and its population to cannibalism. In a campaign that speaks more about sheer determination than military sophistication, the Russians turned the Germans and drove them back across the Don. But the cost was staggering. A million Russian soldiers were casualties in the defence of Stalingrad, more than twice the population of the city, and more than all the American casualties in the whole of the Second World War. Their memorial is almost as colossal as their tragedy.