Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Ten Thousand a-Year. Volume 3

"To the Right Hon. Lord Drelincourt, My Lord—

"Natrally situated In The Way which I Am With yr lordship Most Unpleasantly Addressing you On A Matter of that Nature most Painful To My feelings Considering My surprising Forlorn Condition, And So Sudden Which Who cd Have A Little While Ago suppos'd. Yr Lordship (of Course) Is Aware That There Is No fault of Mine, But rather My Cursed Parents wh Ought To be Ashamed of Themselves For Their Improper Conduct wh Was never made Acquainted with till Lately with Great Greif. Alas. I Only Wish I Had Never Been Born, or Was Dead and Cumfortable in An Erly Grave. I Humbly, My Lord, Endevoured To Do My Duty when In the Upper Circles and Especially to the People, which I Always voted for, Steady, in The House, And Never Injured Any One, Much less you, My Lord, if You Will Believe Me, For I surely wd. Not Have Come Upon You In the Way I did My Lord But Was obliged, And Regret, &c. I Am Most Truly Miserable, Being (Betwixt You and Me, my Lord) over Head and Years in debt, And Have Nothing To pay With and out of The House So Have No Protection and Fear am Going Very Fast To ye. Dogs, my Lord, Swindle O'Gibbet, Esq. M.P. Owes me £500 (borrowed Money) and Will not Pay and is a Shocking Scamp, but (depend upon it) I will stick To Him Like a Leach. Of Course Now your Lordship Is Got into ye Estate &c. you Will Have ye Rents, &c., but Is Not Half The Last Quarter Mine Seeing I Was in possession wh is 9-10ths of ye law. But gave it All up To you willingly Now For what can't Be cur'd, Must Be Indur'd can yr lordship Get me Some Foreign Appointment Abroad wh shd be much obliged for and Would Get Me out of the Way of Troubling yr lordship about the Rents wh freely give Up.

You Being Got To that High Rank wh was to Have Been mine can do What You please doubtless. Am Sorry To Say I am Most Uncommon Hard Up Since I Have Broke up. And am nearly Run Out. Consider my Lord How Easy I Let You Win ye Property. When might Have Given Your Lordship Trouble. If you will Remember this And Be So obliging to Lend me a £10 Note (For ye Present) Will much oblige

"Your Lordship's to Command,"Most obedt"Tittlebat Titmouse."P.S.—I Leave This with my Own Hand That you May be Sure and get it. Remember me to Miss A. and Lady D."

Mr. Titmouse contented himself with telling his new friend merely the substance of the above epistle, and, having sealed it up, he asked his companion if he were disposed for a walk to the West End; and on being answered in the affirmative, they both set off for Lord Drelincourt's house in Dover Street. When they had reached it, his friend stepped to a little distance; while Titmouse, endeavoring to assume a confident air, hemmed, twitched up his shirt-collar, and knocked and rang with all the boldness of a gentleman coming to dinner. Open flew the door in a moment; and—

"My Lord Drelincourt's—isn't it?" inquired Titmouse, holding his letter in his hand, and tapping his ebony cane pretty loudly against his legs.

"Of course it is! What d'ye want?" quoth the porter, sternly, enraged at being disturbed at such an hour by such a puppy of a fellow as then stood before him—for the bloom was off the finery of Titmouse; and who that knew the world would call, and with such a knock, at seven o'clock with a letter? Titmouse would have answered the fellow pretty sharply, but was afraid of endangering the success of his application: so, with considerable calmness, he replied—

"Oh—Then have the goodness to deliver this into his Lordship's own hand—it's of great importance."

"Very well," said the porter, stiffly, not dreaming what a remarkable personage was the individual whom he was addressing, and the next instant shut the door in his face.

"Dem impudent blackguard!" said he, as he rejoined his friend—his heart almost bursting with mortification and fury; "I've a great mind to call to-morrow, 'pon my soul—and get him discharged!"

He had dated his letter from his lodgings, where, about ten o'clock on the ensuing morning, a gentleman—in fact, Lord Drelincourt's man of business—called, and asking to see Mr. Titmouse, gave into his hands a letter, of which the following is a copy:—

"Dover Street, Wednesday Morning."Lord Drelincourt, in answer to Mr. Titmouse's letter, requests his acceptance of the enclosed Bank of England Note for Ten Pounds.

"Lord D. wishes Mr. Titmouse to furnish him with an address, to which any further communications on the part of Lord D. may be addressed."

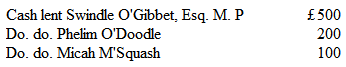

On repairing to the adjoining tavern, soon after receiving the above most welcome note, Mr. Titmouse fortunately (!) fell in with his friend, and, with somewhat of an air of easy triumph, showed him Lord Drelincourt's note, and its enclosure. Some time afterwards, having smoked each a couple of cigars and drank a couple of tumblers of brandy and water, Mr. Titmouse's companion got very confidential, and in a low whisper said, that he had been thinking over Mr. Titmouse's case ever since they were talking together the night before; and for five pounds would put him in the way of escaping all danger immediately, provided no questions were asked by Mr. Titmouse; for he, the speaker, was running a great risk in what he was doing. Titmouse placed his hand over his heart, exclaiming, "Honor—honor!" and having called for change from the landlord, gave a five-pound note into the hand of his companion, who thereupon, in a mysterious undertone, told him that by ten o'clock the next morning he would have a hackney-coach at the door of his lodgings, and would at once convey him safely to a vessel then in the river, and bound for the south of France; where Mr. Titmouse might remain till he had in some measure settled his affairs with his creditors. Sure enough, at the appointed time, the promised vehicle drew up at the door of the house where Titmouse lodged; and within a few moments' time he came down-stairs with a small portmanteau, and entered the coach where sat his friend, evidently not wishing to be recognized or seen by anybody passing. They talked together earnestly and eagerly as they journeyed eastward; and just as they arrived opposite a huge dismal-looking building, with a large door, and immensely high walls, the coach stopped. Three or four persons were standing, as if they had been in expectation of an arrival; and, requesting Mr. Titmouse to alight for a moment, his friend opened the coach door from within, and let down the steps. The moment that poor Titmouse had got out, he was instantly surrounded, and seized by the collar by those who were standing by; his perfidious "friend" had disappeared; and almost petrified with amazement and fright, and taken quite off his guard by the suddenness of the movement, poor Titmouse was hurried through the doorway of the King's Bench Prison, the three Jews following close at his heels, and conducted into a very gloomy room. There he seemed first to awake to the horrors of his situation, and went into a paroxysm of despair and fury. He sprang madly towards the door, and on being repulsed by those standing beside him, stamped violently about the room, shouting, "Murder, murder! thieves!" Then he pulled his hair, shook his head with frantic vehemence, and presently sank into a seat, from which, after a few moments, he sprang wildly, and broke his cane into a number of pieces, scattering them about the room like a madman. Then he cried passionately; more, in fact, like a frantic school-girl, than a man; and struck his head violently with his fists. All this while the three Jews were looking on with a grin of devilish gratification at the little wretch's agony. His frenzy lasted so long that he was removed to a strong room, and threatened with being put into a strait waistcoat if he continued to conduct himself so outrageously. The fact of his being thus safely housed, soon became known, and within a day or two's time, the miserable little fellow was completely overwhelmed by his creditors; who, absurd and unavailing as were their proceedings, came rushing down upon him, one after another, with as breathless an impetuosity as if they had thought him a mass of solid gold, which was to become the spoil of him who could first seize it. The next day his fate was announced to the world by paragraphs in all the morning newspapers, which informed their readers that "yesterday Mr. Titmouse, late M.P. for Yatton, was secured by a skilful stratagem, just as he was on the point of quitting this country for America, and lodged in the King's Bench Prison, at the suit of three creditors, to the extent of upwards of sixty thousand pounds. It is understood that his debts considerably exceed the sum of one hundred and fifty thousand pounds." As soon as he had become calm enough to do so—viz. three or four days after his incarceration—he wrote a long, dismal epistle to Lord Drelincourt, and also one to Miss Aubrey, passionately reminding them both that he was, after all, of the same blood with themselves, only luck had gone for them and against him, and therefore he hoped they would "remember him, and do something to get him out of his trouble." He seemed to cling to them as though he had a claim upon them—instead of being himself Lord Drelincourt's debtor to the amount of, at least, twenty thousand pounds, had his Lordship, instead of inclining a compassionate ear to his entreaties, chosen to fling his heavy claim, too, into the scale against him. This, however, was a view of the case which never occurred to poor Titmouse. Partly of their own accord, and partly at Miss Aubrey's earnest entreaty, Lord Drelincourt and Mr. Delamere went to the King's Bench Prison, and had a long interview with him—his Lordship being specially anxious to ascertain, if possible, whether Titmouse had been originally privy to the monstrous fraud by means of which he had succeeded in possessing himself of Yatton, at so fearful a cost of suffering to those whom he had deprived of it. While he was chattering away, more after the fashion of a newly-caged ape, than a MAN, with eager and impassioned tone and gesticulation—with a profuse usage of his favorite phraseology—"'Pon my soul!" "'Pon my life!" "By Jove!" and of several shocking oaths, for which he was repeatedly and sternly rebuked by Lord Drelincourt, with what profound and melancholy interest did the latter regard the strange being before him, and think of the innumerable extraordinary things which he had heard concerning him! Here was the widowed husband of the Lady Cecilia, and son-in-law of the Earl of Dreddlington—that broken pillar of pride!—broken, alas! in the very moment of imaginary magnificence! Here was the late member of Parliament for the borough of Yatton, whose constituency had deliberately declared him possessed of their complete confidence!—on whose individual vote had several times depended the existence of the king's ministry, and the passing of measures of the greatest possible magnitude! This was he whom all society—even the most brilliant—had courted as a great lion.—This was the sometime owner of Yatton! who had aspired to the hand of Miss Aubrey! who had for two years revelled in every conceivable species of luxury, splendor, and profligacy! Here was the individual at whose instance—at whose nod—Lord Drelincourt had been deprived of his liberty, ruthlessly torn from the bleeding bosom of his family, and he and they, for many, many weary months, subjected to the most harassing and heart-breaking privations and distresses! On quitting him, Lord Drelincourt put into his hand a ten-pound note, with which Titmouse seemed—though he dared not say so—not a little disappointed. His Lordship and Mr. Delamere were inclined, upon the whole—for Titmouse had displayed some little cunning—to believe that he had not been aware of his illegitimacy till the issue of the ecclesiastical proceedings had been published; but from many remarks he let fall, they were satisfied that Mr. Gammon must have known the fact from a very early period—for Titmouse spoke freely of the constant mysterious threats he was in the habit of receiving from Mr. Gammon. Lord Drelincourt had promised Titmouse to consider in what way he could serve him; and during the course of the day instructed Mr. Runnington to put the case into the hands of some attorney of the Insolvent Debtors' Court, with a view of endeavoring to obtain for the unfortunate little wretch the "benefit of the Act." As soon as the course of practice would admit of it, he was brought up in the ordinary way before the court, which was quite crowded by persons either interested as creditors, or curious to see so celebrated a person as Tittlebat Titmouse. The commissioners were astounded at the sight of the number and magnitude of his liabilities—a hundred thousand pounds at least!—against which he had nothing to set except the following items:—

—together with some other similar but lesser sums; but for none of them could he produce any vouchers, except for the sum lent to the Hon. Empty Belly, who had been imprudent enough to give him his I. O. U. Poor Titmouse's discharge was most vehemently opposed on the part of his creditors—particularly the three Jews—whose frantic and indecorous conduct in open court occasioned the chief commissioner to order them to be twice removed. They would have had Titmouse remanded to the day of his death! After several adjourned and lengthened hearings, the court pronounced him not to be entitled to his discharge till he should have remained in prison for the space of eighteen calendar months; on hearing which he burst into a fit of loud and bitter weeping, and was removed from court, wringing his hands and shaking his head in perfect despair. As soon as this result had been communicated to Lord Drelincourt, (who had taken special care that his name should not be among those of Mr. Titmouse's creditors,) he came to the humane determination of allowing him a hundred and fifty pounds a-year for his life, payable weekly, to commence from the date of his being remanded to prison.—For the first month or so he spent all his weekly allowance in brandy and water and cigars, within three days after receiving it. Then he took to gambling with his fellow-prisoners; but, all of a sudden, he turned over quite a new leaf. The fact was, that he had become intimate with an unfortunate literary hack, who used to procure small sums by writing articles for inferior newspapers and magazines; and at his suggestion, Titmouse fell to work upon several quires of foolscap: the following being the title given to his projected work by his new friend—

"Ups and Downs:BeingMemoirs of My Life,byTittlebat Titmouse, Esq.,Late M. P. for Yatton."He got so far on with his task as to fill three quires of paper; and it is a fact that a fashionable publisher got scent of the undertaking, came to the prison, and offered him three hundred pounds for his manuscript, provided only he would undertake that it should fill three volumes. This greatly stimulated Titmouse; but unfortunately he fell ill before he had completed the first volume, and never, during the remainder of his confinement, recovered himself sufficiently to proceed further with his labors. I once had an opportunity of glancing over what he had written, which was really very curious, but I do not know what has since become of it. During the last month of his imprisonment he became intimate with a villanous young Jew attorney, who, under the pretence of commencing proceedings in the House of Lords (!) for the recovering of the Yatton property once more from Lord Drelincourt, contrived to get into his own pockets more than one-half of the weekly sum allowed by that nobleman to his grateful pensioner! On the very day of his discharge, Titmouse—not comprehending the nature of his own position—went off straight to the lodgings of Mr. Swindle O'Gibbet to demand payment of the five hundred pounds due to him from that honorable gentleman, to whom he became a source of inconceivable vexation and torment. Following him about with a sort of insane and miserable pertinacity, Titmouse lay in wait for him now at his lodgings—then at the door of the House of Commons; dogged him from the one point to the other; assailed him with passionate entreaties and reproaches in the open street: went to the public meetings over which Mr. O'Gibbet presided, or where he spoke, (always on behalf of the rights of conscience and the liberty of the subject,) and would call out—"Pay me my five hundred pounds! I want my money! Where's my five hundred pounds?" on which Mr. O'Gibbet would point to him, call him an "impostor! a liar!" furiously adding that he was only hired by the enemies of the people to come and disturb their proceedings: whereupon (which was surely a new way of paying old debts) Titmouse was always shuffled about—his hat knocked over his eyes—and he was finally kicked out, and once or twice pushed down from the top to the bottom of the stairs. The last time that this happened, poor Titmouse's head struck with dreadful force against the banisters; and he lay for some time stunned and bleeding. On being carried to a doctor's shop, he was shortly afterwards seized with a fit of epilepsy. This seemed to have given the finishing stroke to his shattered intellects; for he sank soon afterwards into a state of idiocy. Through the kindness and at the expense of Lord Drelincourt, he was admitted an inmate of a private lunatic asylum, in the Curtain Road, near Hoxton, where he still continues. He is very harmless; and after dressing himself in the morning with extraordinary pains—never failing to have a glimpse visible of his white pocket-handkerchief out of the pocket in the breast of his surtout—nor to have his boots very brightly polished—he generally sits down with a glass of strong and warm toast and water, and a colored straw, which he imagines to be brandy and water, and a cigar. He complained, at first, that the brandy and water was very weak; but he is now reconciled to it, and sips his two tumblers daily with an air of tranquil enjoyment. When I last saw him he was thus occupied. On my approaching him, he hastily stuck his quizzing-glass into his eye, where it was retained by the force of muscular contraction, while he stared at me with all his former expression of rudeness and presumption. 'Twas at once a ridiculous and a mournful sight.

I should have been very glad, if, consistently with my duty as an impartial historian, I could have concealed some discreditable features in the conduct of Mr. Tag-rag, subsequently to his unfortunate bankruptcy. I shall not, however, dwell upon them at greater length than is necessary. His creditors were so much dissatisfied with his conduct, that not one of them could be prevailed upon to sign his certificate,23 by which means he was prevented from re-establishing himself in business, even had he been able to find the means of so doing; since, in the eye of our law, any business carried on by an uncertificated bankrupt, is so carried on by him only as a trustee for his creditors.—His temper getting more and more soured, he became at length quite intolerable to his wife, whom he had married only for her fortune, (£800, and the good-will of her late husband's business, as a retail draper and hosier, in Little Turn-stile, Holborn.) When he found that Mrs. Tag-rag would not forsake her unhappy daughter, he snapped his fingers at her, and, I regret to say, told her that she and her daughter, and her respectable husband, might all go to the devil together—but he must shift for himself; and, in plain English, he took himself off. Mr. Dismal Horror found that he had made a sad business of it, in marrying Miss Tag-rag, who brought him two children in the first nineteen months, and seemed likely to go on at that rate for a long time to come, which made Mr. Horror think very seriously of following the example of his excellent father-in-law—viz. deserting his wife. They had contrived to scrape together a bit of a day-school for young children, in Goswell Street; but which was inadequate to the support of themselves, and also of Mrs. Tag-rag, who had failed in obtaining the situation of pew-opener to a neighboring dissenting chapel. The scheme he had conceived, he soon afterwards carried into effect; for, whereas he went out one day saying he should return in an hour's time, he nevertheless came not back at all. Burning with zeal to display his pulpit talents, he took to street-preaching, and at length succeeded in getting around him a group of hearers, many of them most serious and attentive pickpockets, with dexterous fingers and devout faces, wherever he held forth, which was principally in the neighborhood of the Tower and Smithfield—till he was driven away by the police, who never interfered with his little farce till he had sent his hat round; when, to preserve the peace, they would rush in, disperse the crowd, and taking him into custody, convey him to the police-office, where, in spite of his eloquent defences, he several times got sentenced to three months' imprisonment, as an incorrigible disturber of the peace, and in league with the questionable characters, who—the police declared—were invariably members of every congregation he addressed. One occasion of his being thus taken into custody was rather a singular one:—Mr. Tag-rag happened to be passing while he was holding forth, and, unable to control his fury, made his way immediately in front of the impassioned preacher; and, sticking his fists in his side a-kimbo, exclaimed, "Aren't you a nice young man now?"—which quite disconcerted his pious son-in-law, who threw his hymn-book in his father-in-law's face, which bred such a disturbance that the police rushed in, and took them both off to the police-office; where such a scene ensued as beggars all description. What has since become of Mr. Horror, I do not know; but the next thing I heard of Mr. Tag-rag was his entering into the employ of no other a person than Mr. Huckaback, who had been for some time settled in a little shop in the neighborhood of Leicester Square. Having, however, inadvertently shown in to Mr. Huckaback one of the creditors to whom he had given special orders to be denied, that gentleman instantly turned him out of the shop, in a fury, without character or wages; which latter, nevertheless, Tag-rag soon compelled him, by the process of the Court of Bequests, to pay him; being one week's entire salary. In passing one day a mock auction, on the left-hand side of the Poultry, I could not help pausing to admire the cool effrontery with which the Jew in the box was putting up showy but worthless articles to sale to four patient puffers—his entire audience—and who bid against one another in a very business-like way for everything which was thus proposed for their consideration. Guess my astonishment and concern, when one of the aforesaid puffers, who stood with his back towards me, happened to look round for a moment, to discover in him my friend Mr. Tag-rag!! His hat was nicely brushed, but all the "nap" was off; his coat was clean, threadbare, and evidently had been made for some other person; under his arm was an old cotton umbrella; and in his hands, which were clasped behind him, were a pair of antiquated black gloves, doubled up, only for show, evidently not for use. Notwithstanding, however, he had sunk thus low, there happened to him, some time afterwards, one or two surprising strokes of good fortune. First of all, he contrived to get a sum of three hundred pounds from one of his former debtors, who imagined that Tag-rag was authorized by his assignees to receive it. Nothing, however, of the kind; and Tag-rag quietly opened a small shop in the neighborhood of St. George's in the East, and began to scrape together a tolerable business. Reading one day a flourishing speech in Parliament, on the atrocious enormity of calling upon Dissenters to pay Church-rates—it occurred to Mr. Tag-rag as likely to turn out a good speculation, and greatly increase his business, if he were to become a martyr for conscience sake; and after turning the thing about a good deal in his mind, he determined on refusing to pay the sum of twopence-halfpenny, due in respect of a rate which had been recently made for the repair of the church steeple, then very nearly falling down. In a very civil and unctuous manner, he announced to the collector his determination to refuse the payment on strictly conscientious grounds. The collector expostulated—but in vain. Then came the amazed churchwardens—Tag-rag, however, was inflexible. The thing began to get wind, and the rector, an amiable and learned man—and an earnest lover of peace in his parish—came to try his powers of persuasion—but he might have saved himself the trouble; 'twas impossible to divert Mr. Tag-rag's eye from the glorious crown of martyrdom he had resolved upon earning. Then he called on the minister of the congregation where he "worshipped," and with tears and agitation unbosomed himself upon the subject, and besought his counsel. The intelligent and pious pastor got excited; so did his leading people. A meeting was called at his chapel, the result of which was a declaration that Mr. Tag-rag's conduct was most praiseworthy and noble—that he had taken his stand upon a great principle—and deserved to be supported. Several leading members of the congregation, who had never dealt with him before, suddenly became customers of his. The upshot of the matter was, that after a prodigious stir, Mr. Tag-rag became a victim in right earnest; and was taken into custody by virtue of a writ De Contumace Capiendo, amid the indignant sympathy and admiration of all those enlightened persons who shared his opinions. In a twinkling he shot up, as it were, into the air like a rocket, and became popular, beyond his most sanguine expectations. The name of the first Church-rate martyr went the round of every paper in the United Kingdom; and at length came out a lithographed likeness of his odious face, with his precious autograph appended, so—