Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Ten Thousand a-Year. Volume 3

A day or two after Lord Drelincourt's return to town, Messrs. Mudflint and Bloodsuck received a very pressing invitation to York Castle, whose hospitable owners would receive no refusal. In plain English, they were both taken in execution on the same day, by virtue of two writs of capias ad satisfaciendum, for the damages and costs due to Mr. Wigley; viz. £2,960, 16s. 4d. from Smirk Mudflint, and £2,760, 19s. from Barnabas Bloodsuck, junior. Poor Mr. Mudflint! In vain—in vain had been his Sunday evenings' lectures for the last three months, on the errors which pervaded all systems of jurisprudence which annexed any pecuniary liabilities to political offences, instead of leaving the evil to be redressed by the spontaneous good sense of society. A single tap of the sheriff's officer on the eloquent lecturer's shoulder, upset all his fine speculations; just as Corporal Trim said, that one shove of the bayonet was worth all Dr. Slop's fine metaphysical discourses upon the art of war!

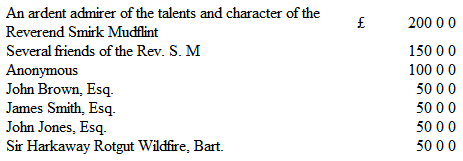

In the next Yorkshire Stingo, (which, alas! between ourselves, was very nearly on its last legs,) there appeared one of, I must own, the most magnificent articles of the kind which I ever read, upon the atrocious and unparalleled outrage on the liberties of the subject, which had been committed in the incarceration of the two patriots—the martyr-patriots—Mudflint and Bloodsuck. On that day, it said, the sun of liberty had set on England forever—in fact, for it was a time for speaking out—it had gone down in blood. The enlightened patriot, Mudflint, had at length fallen before the combined forces of bigotry and tyranny, which were now, in the shape of the Church of England and the aristocracy, riding rough-shod over the necks of Englishmen. In his person lay prostrate the sacred rights of conscience, and the inalienable liberty of Englishmen. He had stood forth, nobly foremost, in the fray between the people and their oppressors; and he had fallen!—but he felt how dulce et decorum it was, pro patriâ mori! He felt prouder and happier in his bonds than could ever feel the splendid fiend at F–m, in all his blood-stained magnificence! It then called upon the people, in vivid and spirit-stirring language, to rise against their tyrants like one man, and the days of their oppressors were numbered; and stated that the first blow was already struck against the black and monstrous fabric of priestcraft and tyranny; for that a SUBSCRIPTION had been already opened on behalf of Mr. Mudflint and Mr. Bloodsuck, for the purpose of discharging the amount of debt and costs for which they had been so infamously deprived of their liberty. An unprecedented sensation had—it seemed—been already excited; and a reference to the advertising columns of their paper would show that the work went bravely on. The friends of religious and civil liberty all over the country were roused; they had but to continue their exertions, and the majesty of the people would be heard in a voice of thunder. This article produced an immense sensation in that part of York Castle where the patriots were confined, and in the immediate neighborhood of the office of the Yorkshire Stingo, (in fact, it had emanated from the masterly pen of Mudflint himself.) Sure enough, on referring to the advertising columns of the Stingo, the following did appear fully to warrant the tone of indignant exultation indulged in by the editor:—

Subscriptions already received (through C. Woodlouse) towards raising a fund for the liberation of the Reverend Smirk Mudflint and Barnabas Bloodsuck, junior, Esq., at present confined in York Castle.

Now, to conceal nothing from the reader, I regret being obliged to inform him that, with the exception of Sir H. R. Wildfire, Bart., the above noble-spirited individuals, whom no one had ever heard of in or near to Grilston, or, in fact, anywhere else, had their local habitation and their name only in the fertile brain of the Rev. Mr. Mudflint; who had hit upon this device as an effectual one for getting up the steam, (to use a modern and significant expression,) and giving that mighty impulse which was requisite to burst the bonds of the two imprisoned patriots.

Sir Harkaway's name was in the list, to be sure, but that was on the distinct understanding that he was not to be called on to pay one farthing; the bargain being, that if he would give the sanction of his name to Messrs. Mudflint and Bloodsuck, they would allow him to have the credit, gratis, of so nobly supporting the Liberal cause.

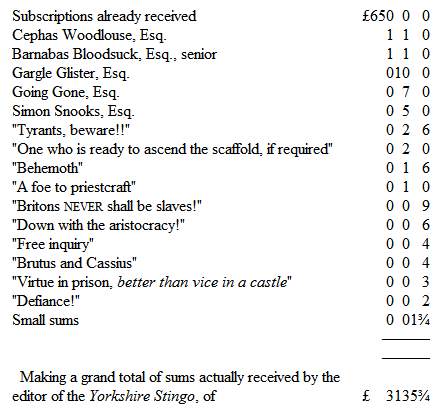

The following, however, were real and bonâ fide names and subscriptions collected, with immense exertion, during the ensuing three weeks; and though, when annexed to the foregoing flourishing commencement of the list, they give it, I must own, a somewhat tadpole appearance, yet here they are:—

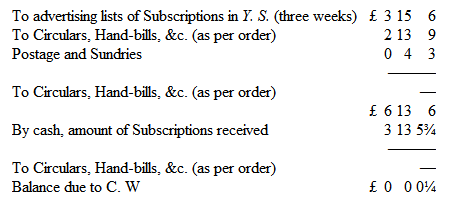

Certainly this was "not as good as had been anticipated"—as the editor subsequently owned in his leading article—and asked, with sorrowful indignation, how the people could expect any one to be true to them if they were not true to themselves! "Our cheeks," said he, "tingle with shame on looking at the paltry list of additional contributions—'Oh, lame and impotent conclusion' to so auspicious a commencement!"—This was very fine indeed. It came very well from Mr. Woodlouse in his editorial capacity; but Mr. Woodlouse, in his capacity as a man of business, was a very different person. Alas! that it should fell to my lot to inquire, in my turn, with sorrowful indignation—was there NO honor among thieves? But, to come to the point, it fell out in this wise. Patriots must live, even in prison; and Mr. Mudflint, being sorely pressed, wrote a letter to his "Dear Woodlouse," asking for the amount of subscriptions received up to that date. He received, in return, a most friendly note, addressed "My dear Mudflint," full of civilities and friendly anxieties—hoping the air of the Castle agreed with him—assuring him how he was missed from the Liberal circle, and that he would be welcomed with open arms if ever he got out—and—enclosing a nicely drawn out debtor and creditor account!! headed—

The Rev. Smirk Mudflint and Barnabas Bloodsuck, Esq., in account with Cephas Woodlouse, [in which every farthing of the above sum of £3, 13s. 5¾d. was faithfully set down to the credit side, to be sure; but, alas!—on the DEBIT side stood the following!]—

On perusing the above document, so pregnant with perfidy and extortion, Mr. Mudflint put it into his pocket, and, slipping off to his sleeping-room, closed the door, took off his garters, and, with very deadly intentions towards himself was tying them together—casting a ghastly glance, occasionally, at a great hook in the wall, which he could just reach by standing on a stool—when he was discovered, and removed with his hands fastened behind him, "to the strong room," where he was firmly attached to a heavy wooden bench, and left to his meditations. Solitude and reflection restored the afflicted captive to something like composure and resignation; and after meditating long and deeply on the selfishness and worthlessness of worldly friendship, his thoughts gradually turned towards a better place—a haven of rest—viz. the Insolvent Debtors' Court.

The effect of this infamous treatment upon his fellow-captive, Bloodsuck, was quite different. Having sworn one single prodigious oath, he enclosed the above account, and sent it off to his father, in the following pithy letter:—

"York Castle, Dec. 29, 18— "Dear Father,—Read the enclosed! and then sell up Woodlouse.—Your dutiful Son, B. Bloodsuck, Jun."

The old gentleman, on reading this laconic epistle, and its enclosure, immediately issued execution against Woodlouse, on a cognovit of his for £150, which he had given to the firm of Bloodsuck and Son for the balance of a bill of theirs for defending him unsuccessfully against an action for an infamous libel. Nobody would bid anything for his moribund "Stingo;" he had no other effects, and was immediately taken in execution, and sent to York Castle, where he, Bloodsuck, and Mudflint, whenever they met, could hardly be restrained from tearing one another's eyes out.

'Tis thus that reptiles of this sort prey upon each other!—To "begin nothing of which you have not well considered the end," is a saying, the propriety of which every one recognizes when he hears it enunciated, but no one thinks of in the conduct of actual life; and what follows, will illustrate the truth of my reflection. It seemed a capital notion of Mudflint's to send forth such a splendid list of sham subscribers, and it was natural enough for Mr. Bloodsuck to assent to it, and Mr. Woodlouse to become the party to it which he did—but who could have foreseen the consequences? A quarrel among rogues is almost always attended with ugly and unexpected consequences to themselves. Now, here was a mortal feud between Mr. Woodlouse on the one side, and Messrs. Mudflint and Bloodsuck on the other; and in due time they all applied, as a matter of course, for relief under the Insolvent Debtors' Act. Before they got to the question concerning the nature of the debt—viz. the penalties in an action for the odious offence of bribery—in the case of Mr. Mudflint, he had to encounter a very serious and truly unexpected obstacle—viz. he had given in, with the minutest accuracy, the items of the subscription, amounting to £3, 13s. 5¾d., but had observed the most mysterious and (as he might have supposed) politic silence concerning the greater sum of £650, and which had been brought under the notice of the creditors of Messrs. Mudflint and Bloodsuck by Mr. Woodlouse. On the newspaper acknowledging the receipt of that large sum being produced in court, Mr. Mudflint made very light of the matter, simply smiling and shrugging his shoulders; but when Mr. Woodlouse was called as a witness, you may guess the consternation of Mr. Mudflint, on hearing him swear that he had certainly never himself received the money, but had no doubt of Mr. Mudflint having done so—which, in fact, had always been his impression; for when Mr. Mudflint had furnished him with the list, which he handed up to court, in Mudflint's handwriting, he inserted it in his paper as a matter of course—taking it to be a bonâ fide and matter-of-fact transaction. The evident consternation of Mudflint satisfied all who heard him of his villany, and of the truth and honesty of Woodlouse, who stuck to this new version of the affair manfully. But this opened quite a new view of his position to Mr. Bloodsuck; who, on finding that he must needs adopt either Mudflint's or Woodlouse's account of the matter, began to reflect upon the disagreeable effect it would have, thereafter, upon the connection and character of the respectable firm of Bloodsuck and Son, for him to appear to have been a party to such a shocking fraud upon the public, as a sham list of subscribers, and to so large an amount. He therefore swore stoutly that he, too, had always been under the impression that Mr. Mudflint had received the £650!! and very much regretted to find that that gentleman must have been appropriating so large a sum to himself, instead of being now ready to divide it between their respective creditors. This tallied with Woodlouse's account of the matter; and infinitely disgusted was that gentleman at finding himself so cleverly outwitted by Bloodsuck. On this Mudflint turned with fury upon Bloodsuck, and he upon Mudflint, who abused Woodlouse; and eventually the commissioners, unable to believe any of them, remanded them all, as a pack of rogues, till the next court day; addressing a very stern warning to Mr. Mudflint, concerning the serious consequences of his persisting in fraudulently concealing his property from his creditors. By the time of his being next brought up, the persecuted Mudflint had bethought himself of a bold mode of corroborating the truth of his explanation of that accursed first list of subscribers—viz. summoning Sir Harkaway Rotgut Wildfire as a witness in his behalf; whom he confidently asked whether, for all his name appeared in the subscription list, he had really ever given one farthing of the £50 there mentioned? Now, had our friend Mudflint been a long-headed man, he would not have taken this step; for Sir Harkaway could never be supposed capable of bringing himself to admit that he had been a party to such a dirty deceit upon the public as he was now charged with. On a careful consideration of the circumstances, therefore, Sir Harkaway, having an eye solely to his own credit, first said, with a somewhat haughty, but at the same time embarrassed air, that he was not in the habit of allowing his name to appear in such lists without his having actually paid the sum named, then, on being pressed, he swore that he thought he must have paid it; then, that he had very little doubt on the subject; then, that he had no doubt on the matter at all; then, that he knew that in point of fact he had advanced the money; and finally, that he then recollected all the circumstances most distinctly!—On this complete confirmation of the roguery of Mudflint, he was instantly reprimanded severely, and remanded indefinitely; the whole court believing that he had appropriated to his own use every farthing of the £650, defrauding even his fellow-prisoner, Mr. Bloodsuck. It was a good while before Mudflint recovered from the effects of this astounding conduct of Sir Harkaway. When his wits had returned to him, he felt certain that, somewhere or other, he had a letter from Sir Harkaway which would satisfy everybody of the very peculiarly unpleasant position in which the worthy baronet had placed himself. And sure enough, on desiring his wife to institute a rigorous search among his papers, she succeeded in discovering the following remarkable document, which she at once forwarded to her disconsolate husband:—

"View-Hallo Hall, 27th Dec. 18—."Sir,"I have a considerable regard for your services to liberty, (civil and religious,) and am willing to serve you in the way you wish. You may put me down, therefore, in the list for anything you please, as my name carries weight in the county—but, of course, you know better than to kill your decoy duck."

"Sir, your obedient servant,"H. R. Wildfire."The Rev. S. Mudflint, &c., &c."

This unfortunate letter, in the first frenzy of his rage and exultation, Mudflint instantly forwarded, with a statement of facts, to the editor of the True Blue newspaper, which carried it into every corner of the county on the very next morning; and undoubtedly gave thereby a heavy blow and a great discouragement to the Liberal cause all over Yorkshire; for Sir Harkaway had always been looked upon as one of its very stanchest and most powerful supporters.

CHAPTER XII

Very shortly after Messrs. Mudflint and Bloodsuck had gone to pay this, their long-expected visit, to the governor of York Castle, Mr. Parkinson required possession of the residence of each of them, in Yatton, to be delivered up to him on behalf of Lord Drelincourt, allowing a week's time for the removal of the few effects of each; after which period had elapsed, the premises in question were completely cleared of everything belonging to their late odious occupants—who, in all human probability, would, infinitely to the delight of Dr. Tatham and all the better sort of the inhabitants, never again be there seen or heard of. In a similar manner another crying nuisance—viz. the public-house known by the name of The Toper's Arms—was got rid of; it having been resolved upon by Lord Drelincourt, that there should be thenceforth but one in Yatton, viz.,—the quiet, old, original Aubrey Arms, and which was quite sufficient for the purposes of the inhabitants. Two or three other persons who had crept into the village during the Titmouse dynasty were similarly dealt with, infinitely to the satisfaction of those left behind; and by Christmas-day the village was beginning to show signs of a return to its former condition. The works going on at the Hall gave an air of cheerful bustle and animation to the whole neighborhood, and afforded extensive employment at a season of the year when it was most wanted. The chapel and residence of the Rev. Mr. Mudflint underwent a rapid and remarkable alteration. The fact was, that Mr. Delamere had conceived the idea, which, with Lord Drelincourt's consent, he proceeded to carry immediately into execution, of pulling down the existing structure, and raising in its stead a very beautiful school, and filling it with scholars, and providing a matron for it, by way of giving a pleasant surprise to Kate on her return to Yatton. He engaged a well-known architect, who submitted to him a plan of a very beautiful little Gothic structure, adapted for receiving some eighteen or twenty scholars, and also affording a permanent residence for the mistress. The scheme being heartily approved of by Mr. Delamere and Dr. Tatham, whom he had taken into his counsels in the affair, they received a pledge that the school should be completed and fit for occupation within three months' time. There was to be, in the front, a small and tasteful tablet, bearing the inscription—

C. AFundatrix18—The mistress of Kate's former school gladly relinquished a similar situation which she held in another part of the county, in order to return to her old one at Yatton; and Dr. Tatham was, in the first instance, to select the scholars, who were to be clothed at Delamere's expense, in the former neat and simple attire which had been adopted by Miss Aubrey. How he delighted to think of the charming surprise which he was thus preparing for his lovely mistress, and by which, at the same time, he was securing for her a permanent and interesting memento in the neighborhood!

About this time there came a general election; the nation being thoroughly disgusted with the character and conduct of a great number of those who had, in the direful hubbub of the last election, contrived to creep into the House of Commons. Public affairs were, moreover, getting daily into a more deranged and dangerous condition: in fact, the Ministers might have been compared to a parcel of little mischievous and venturesome boys, who had found their way into the vast and complicated machinery of some steam-engine, and set it into a fearful motion, which they could neither understand nor govern; and from which they were only too glad to escape safely—if possible—and make way for those whose proper business it was to attend to it. All I have to do, however, at present, with that most important political movement, is to state its effect upon the representation of the borough of Yatton. Its late member, Mr. Tittlebat Titmouse, it completely annihilated. Of course, he made no attempt to stand again; nor, in fact, did any one in the same interest. The Yorkshire Stingo, in its very last number, (of which twelve only were sold,) tried desperately to get up a contest, but in vain. Mr. Going Gone—and even Mr. Glister—were quite willing to have stood—but, in the first place, neither of them could afford to pay his share of the expenses of erecting the hustings; and, secondly, there were insurmountable difficulties in the way of either of them procuring even a pseudo qualification.20 Besides, the more sensible of even the strong Liberal electors had become alive to the exquisite absurdity of returning such persons as Titmouse, or any one of his class. Then the Quaint Club had ceased to exist, partly through the change of political feeling which was rapidly gaining ground in the borough, and partly through terror of the consequences of bribery, of which the miserable fate of Mudflint and Bloodsuck was a fearful instance. In fact, the disasters which had befallen those gentlemen, and Mr. Titmouse, had completely paralyzed and crushed the Liberal party at Yatton, and disabled it from ever attempting to contend against the paramount and legitimate influence of Lord Drelincourt. The result of all this was, the return, without a contest, of the Honorable Geoffrey Lovel Delamere as the representative of the borough of Yatton in the new Parliament; an event, which he penned his first frank21 in communicating to a certain young lady then in London. Nothing, doubtless, could be more delightful for Mr. Delamere; but in what a direful predicament did the loss of his seat place the late member, Mr. Titmouse! Just consider for a moment. Mr. Flummery's promise to him of a "place," had vanished, of course, into thin air—having answered its purpose of securing Mr. Titmouse's vote up to the very moment of the dissolution; an event which Mr. Flummery feared would tend to deprive himself of the honor of serving his country in any official capacity for some twenty years to come—if he should so long live, and the country so long survive his exclusion from office. Foiled thus miserably in this quarter, Mr. Titmouse applied himself with redoubled energy to render available his other resources, and made repeated and most impassioned applications to Mr. O'Gibbet—who never took, however, the slightest notice of any of them: considering very justly that Mr. Titmouse was no more entitled to receive back, than he had originally been to lend, the £500 in question. As for Mr. O'Doodle and Mr. M'Squash they, like himself, were thrown out of Parliament; and no one upon earth seemed able to tell whither they had gone, or what had become of them, though there were a good many people who made it their business to inquire into the matter very anxiously. That quarter, therefore, seemed at present quite hopeless. Then there was an Honorable youngster, who owed him a hundred pounds; but he, the moment that he had lost his election, caused it to be given out to any one interested in his welfare—and there suddenly appeared to be a great many such—that he was gone on a scientific expedition to the South Pole, from which he trusted, though he was not very sanguine, that he should, one day, come back.—All these things drove Mr. Titmouse very nearly beside himself—and certainly his position was a little precarious. When Parliament was dissolved, he had in his pocket a couple of sovereigns, the residue of a five-pound note, out of which, mirabile dictu, he had actually succeeded in teasing Mr. Flummery on the evening of the last division; and these two sovereigns, a shirt or two, the articles actually on his person, and a copy of Boxiana, were all his assets to meet liabilities of about a hundred thousand pounds; and the panoply of Parliamentary "privilege" was dropping off, as it were, hourly. In a very few days' time, in fact, he would be at the mercy of a terrific host of creditors, who were waiting to spring upon his little carcass like so many famished wolves. Every one of them had gone on with his action up to judgment for both debt and costs—and had his Ca. Sa. and Fi. Fa.22 ready for use at an instant's notice. There were three of these injured gentlemen—the three Jews, Israel Fang, Mordecai Gripe, and Mephibosheth Mahar-shalal-hash-baz—who had entered into a solemn vow with one another that they would never lose sight of Titmouse for one moment, by day or by night, whatever pains or expense it might cost them—until, the period of privilege having expired, they should be at liberty to plunge their talons into the body of their little debtor. There were, in fact, at least a hundred of his creditors ready to pounce upon him the instant that he should make the slightest attempt to quit the country. His lodgings consisted, at this time, of a miserable little room in a garret at the back of a small house in Westminster, not far from the Houses of Parliament, and of the two, inferior to the room in Closet Court, Oxford Street, in which he was first presented to the reader. Here he would often lie in bed half the day, drinking weak—because he could not afford strong—brandy and water, and endeavoring to consider "what the devil" he had done with the immense sums of money which had been at his disposal—how he would act, if by some lucky chance he should again become wealthy—and, in short, "what the plague was now to become of him." What was he to do? Whither should he go?—To sea?—Then it must be as a common sailor—if any one would now take him! Or suppose he were to enlist? "Glorious war, and all that," et cetera; but both these schemes pre-supposed his being able to escape from his creditors, who, he had a vehement suspicion, were on the look-out for him in all directions. Every review that he thus took of his hopeless position and prospects, ended in a fiendish degree of abhorrence of his parents, whose fault alone it was—in having brought him into the world—that he had been thus turned out of a splendid estate of ten thousand a-year, and made worse than a beggar. He would sometimes spring out of bed, convulsively clutching his hands together, and wishing himself beside their grave, to tear them out of it. He thought of Mr. Quirk, Mr. Snap, and Mr. Tag-rag, with fury; but whenever he adverted to Mr. Gammon, he shuddered all over, as if in the presence of a baleful spectre. For all this, he preserved the same impudent strut and swagger in the street which had ever distinguished him. Every day of his life he walked towards the scenes of his recent splendor, which seemed to attract him irresistibly. He would pass the late Earl of Dreddlington's house, in Grosvenor Square, staring at it, and at the hatchment suspended in front of it. Then he would wander on to Park Lane, and gaze with unutterable feelings—poor little wretch!—at the house which once had been his and Lady Cecilia's, but was then occupied by a nobleman, whose tasteful equipage and servants were often standing at and before the door. He would, on some of those occasions, feel as though he should like to drop down dead, and be out of all his misery. If ever he met and nodded, or spoke to those with whom he had till recently been on the most familiar terms, he was encountered by a steady stare, and sometimes a smile, which withered his very heart within him, and made the last three years of his life appear to have been but a dream. The little dinner that he ate—for he had almost entirely lost his appetite through long addiction to drinking—was at a small tavern, at only a few doors' distance from his lodgings, and where he generally spent his evenings, for want of any other place to go to; and he formed at length a sort of intimacy with a good-natured and very respectable gentleman, who came nearly as often thither as Titmouse himself, and would sit conversing with him very pleasantly over his cigar and a glass of spirits and water. The oftener Titmouse saw him, the more he liked him; and at length, taking him entirely into his confidence, unbosomed himself concerning his unhappy present circumstances, and still more unhappy prospects. This man was a brother of Mahar-shalal-hash-baz the Jew, and a sheriff's officer, keeping watch upon his movements, night and day, alternately with another who had not attracted Titmouse's notice. After having canvassed several modes of disposing of himself, none of which were satisfactory to either Titmouse or his friend, he hinted that he was aware that there were lots of the enemy on the look-out for him, and who would be glad to get at him; but he knew, he said, that he was as safe as in a castle for some time yet to come; and he also mentioned a scheme which had occurred to him—but this was all in the strictest confidence—viz. to write to Lord Drelincourt, (who was, after all, his relation of some sort or other, and ought to be devilish glad to get into all his, Titmouse's, property so easily,) and ask him for some situation under government, either in France, India, or America, and give him a trifle to set him up at starting, and help him to "nick the bums!" His friend listened attentively, and then protested that he thought it an excellent idea, and Mr. Titmouse had better write the letter and take it at once. Upon this Titmouse sent for pen, ink, and paper; and while his friend leaned back calmly smoking his cigar, and sipping his gin and water, poor Titmouse wrote the following epistle to Lord Drelincourt—the very last which I shall be able to lay before the reader:—