Полная версия

Полная версияThe Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

How? What is this but flying to the old Supra-lapsarian blasphemy of a right of property in God over all his creatures, and destroying that sacred distinction between person and thing which is the light and the life of all law human and divine? Mercy on us! Is not agony, is not the stone, is not blindness, is not ignorance, are not headstrong, inherent, innate, and connate, passions driving us to sin when reason is least able to withhold us, – are not all these punishments, grievous punishments, and are they not inflicted on the innocent babe? Is not this the result infused into the milk not mingled of St. Peter;70 spotting the immaculate begotten, souring and curdling the innocence without sin or malice?71 And if this be just, and compatible with God's goodness, why all this outcry against St. Austin and the Calvinists and the Lutherans, whose whole addition is a lame attempt to believe guilt, where they cannot find it, in order to justify a punishment which they do find?

Ib. p. 379.

But then for the evil of punishment, that may pass further than the action. If it passes upon the innocent, it is not a punishment to them, but an evil inflicted by right of dominion; but yet by reason of the relation of the afflicted to him that sinned, to him it is a punishment.

Here the snake peeps out, and now takes its tail into its mouth. Right of dominion! Nonsense! Things are not objects of right or wrong. Power of dominion I understand, and right of judgment I understand; but right of dominion can have no immediate, but only a relative, sense. I have a right of dominion over this estate, that is, relatively to all other persons. But if there be a jus dominandi over rational and free agents, then why blame Calvin? For all attributes are then merged in blind power: and God and fate are the same:

Strange Trinity! God, Necessity, and the Devil. But Taylor's scheme has far worse consequences than Calvin's: for it makes the whole scheme of Redemption a theatrical scenery. Just restore our bodies and corporeal passions to a perfect equilibrium and fortunate instinct, and, there being no guilt or defect in the soul, the Son of God, the Logos, and Supreme Reason, might have remained unincarnate, uncrucified. In short, Socinianism is as inevitable a deduction from Taylor's scheme as Deism or Atheism is from Socinianism.

In fine.

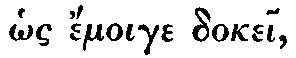

The whole of Taylor's confusion originated in this; – first, that he and his adversaries confound original with hereditary sin; but chiefly that neither he nor his adversaries had considered that guilt must be a noumenon; but that our images, remembrances, and consciousnesses of our actions are phænomena. Now the phænomenon is in time, and an effect: but the noumenon is not in time any more than it is in space. The guilt has been before we are even conscious of the action; therefore an original sin (that is, a sin universal and essential to man as man, and yet guilt, and yet choice, and yet amenable to punishment), may be at once true and yet in direct contradiction to all our reasonings derived from phænomena, that is, facts of time and space. But we ought not to apply the categories of appearance to the

How came it that Taylor did not apply the same process to the congeneric question of the freedom of the will? In half a dozen syllogisms he must have gyved and hand-cuffed himself into blank necessity and mechanic motions. All hangs together. Deny Original Sin, and you will soon deny free will; – then virtue and vice; – and God becomes Abracadabra; a sound, nothing else.

Second Letter to the Bishop of Rochester

Ib. p. 390-1.

To this it is answered as you see, there is a double guilt; a guilt of person, and of nature. That is taken away, this is not: for sacraments are given to persons, not to natures.

I need no other passage but this to convince me that Jeremy Taylor, the angle in which the two apices of logic and rhetoric meet, consummate in both, was yet no metaphysician. Learning, fancy, discursive intellect, tria juncta in uno, and of each enough to have alone immortalized a man, he had; but yet

The Real Presence and Spiritual of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, Proved Against the Doctrine of Transubstantiation.

Perhaps the most wonderful of all Taylor's works. He seems, if I may so say, to have transubstantiated his vast imagination and fancy into subtlety not to be evaded, acuteness to which nothing remains unpierceable, and indefatigable agility of argumentation. Add to these an exhaustive erudition, and that all these are employed in the service of reason and common sense; whereas in some of his Tracts he seems to wield all sorts of wisdom and wit in defence of all sorts of folly and stupidity. But these were ad popellum, and by virtue of the falsitas dispensativa, which he allowed himself.

Epist. dedicatory.

The question of transubstantiation.

I have no doubt that if the Pythagorean bond had successfully established itself, and become a powerful secular hierarchy, there would have been no lack of furious partizans to assert, yea, and to damn and burn such as dared deny, that one was the same as two; two being two in the same sense as one is one; that consequently 2 + 2 = 2 and 1 + 1 = 4. But I should most vehemently doubt that this was the intention of Pythagoras, or the sense in which the mysterious dogma was understood by the thinking part of his disciples, who nevertheless were its professed believers. I should be prepared to find that the true import and purport of the article was no more than this; – that the one in order to its manifestation must appear in and as two; that the act of re-union was simultaneous with that of the self-production, (in the geometrical use of the word 'produce,' as when a point produces, or evolves, itself on each side into a bipolar line), and that the Triad is therefore the necessary form of the Monad.

Even so is the dispute concerning Transubstantiation. I can easily believe that a thousand monks and friars would pretend, as Taylor says, to 'disbelieve their eyes and ears, and defy their own reason,' and to receive the dogma in the sense, or rather in the nonsense, here ascribed to it by him, namely, that the phenomenal bread and wine were the phenomenal flesh and blood. But I likewise know that the respectable Roman Catholic theologians state the article free from a contradiction in terms at least; namely, that in the consecrated elements the noumena of the phenomenal bread and wine are the same with that which was the noumenon of the phenomenal flesh and blood of Christ when on earth.

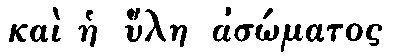

Let M represent a slab or plane of mahogany,

and m its ordinary supporter or under-prop; and

let S represent a slab or plane of silver,

and s its supporter.

Now to affirm that M = S is a contradiction,

or that m = s

but it is no contradiction to say, that on certain occasions

(S having been removed)

s is substituted for m

and that what was M/m

is by the command of the common master changed into M/s

It may be false in fact, but it is not a self-contradiction in the

terms.

The mode in which s subsists in M/s may be inconceivable,

but not more so than the mode in which m subsists in M/m,

or that in which s subsisted in S/s

I honestly confess that I should confine my grounds of opposition to the article thus stated to its unnecessariness, to the want of sufficient proofs from Scripture that I am bound to believe or trouble my head with it. I am sure that Bishop Bull, who really did believe the Trinity, without either Tritheism or Sabellianism, could not consistently have used the argument of Taylor or of Tillotson in proof of the absurdity of Transubstantiation.

Ib. p. ccccxvi.

But for our dear afflicted mother, she is under the portion of a child in the state of discipline, her government indeed hindered, but her worshippings the same, the articles as true, and those of the church of Rome as false as ever.

O how much there is in these few words, – the sweet and comely sophistry, not of Taylor, but of human nature. Mother! child! state of discipline! government hindered! that is to say, in how many instances, scourgings hindered, dungeoning in dens foul as those of hell, mutilation of ears and noses, and flattering the King mad with assertions of his divine right to govern without a Parliament, hindered. The best apology for Laud, Sheldon, and their fellows will ever be that those whom they persecuted were as great persecutors as themselves, and much less excusable.

Ib. s. ii. p. 422.

In Synaxi Transubstantiationem sero definivit Ecclesia; diu satis erat credere, sive sub pane consecrate, sive quocunque modo adesse verum corpus Christi; so said the great Erasmus.

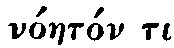

Verum corpus, that is, res ipsissima, or the thing in its actual self, opposed

Ib. s. vi. p. 425.

Now that the spiritual is also a real presence, and that they are hugely consistent, is easily credible to them that believe the gifts of the Holy Ghost are real graces, and a spirit is a proper substance.

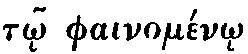

But how the body of Christ, as opposed to his Spirit and to his Godhead, can be taken spiritually, hic labor, hoc opus est. Plotinus says,

Ib. s. vii. p. 426.

So we may say of the blessed Sacrament; Christ is more truly and really present in spiritual presence than in corporal; in the heavenly effect than in the natural being.

But the presence of Christ is not in question, but the presence of Christ's body and blood. Now that Christ effected much for us by coming in the body, which could not or would not have been effected had he not assumed the body, we all, Socinians excepted, believe; but that his body effected it, other than as Christ in the body, where shall we find? how can we understand?

Ib. p. 427.

So when it is said, Flesh and blood shall not inherit the kingdom of God, that is, corruption shall not inherit; and in the resurrection, our bodies are said to be spiritual, that is, not in substance, but in effect and operation.

This is, in the first place, a wilful interpretation, and secondly, it is absurd; for what sort of flesh and blood would incorruptible flesh and blood be? As well might we speak of marble flesh and blood. But in Taylor's mind, as seen throughout, the logician was predominant over the philosopher, and the fancy outbustled the pure intuitive imagination. In the sense of St. Paul, as of Plato and all other dynamic philosophers, flesh and blood is ipso facto corruption, that is, the spirit of life in the mid or balancing state between fixation and reviviscence. Who shall deliver me from the body of this death? is a Hebraism for 'this death which the body is.' For matter itself is but spiritus in coagulo, and organized matter the coagulum in the act of being restored; it is then repotentiating. Stop its self-destruction as matter, and you stop its self-reproduction as a vital organ. In short, Taylor seems to fall into the very fault he reproves in Bellarmine, and with this additional evil, that his reasoning looks more like tricking or explaining away a mystery. For wherein does the Sacrament of the Eucharist differ from that of Baptism, nay, even of grace before meat, when performed fervently and in faith? Here too Christ is present in the hearts of the faithful by blessing and grace. I see at present no other way of interpreting the text so as not to make the Sacrament a mere arbitrary memento, but by an implied negative. In propriety, the word is confined to no portion of corporality in particular. "This (the bread and wine) are as truly my flesh and blood as the phænomena which you now behold and name as such."

Ib. s. ix. p. 429.

From this paragraph I conclude, though not without some perplexity, that by 'the body and blood verily and indeed taken,' we are not to understand body and blood in their limited sense, as contradistinguished from the soul or Godhead of Christ, but as a periphrasis for Christ himself, or at least Christ's humanity. Taylor, however, has misconstrued Phavorinus' meaning though not his words. Spiritualia eterna quoad spiritum. But this is the very depth of the purified Platonic philosophy.

Ib. s. x. p. 430.

But because the words do perfectly declare our sense, and are owned publicly in our doctrine and manner of speaking, it will be in vain to object against us those words of the Fathers, which use the same expressions: for if by virtue of those words 'really,' 'substantially,' 'corporally,' 'verily and indeed,' and 'Christ's body and blood,' the Fathers shall be supposed to speak for Transubstantiation, they may as well suppose it to be our doctrine too; for we use the same words, and therefore those authorities must signify nothing against us, unless these words can be proved in them to signify more than our sense of them does import; and by this truth, many, very many of their pretences are evacuated.

A sophism, dearest Jeremy. We use the words because these early Fathers used them, and have forced our own definitions on them. But should we have chosen these words to express our opinion by, if there had been no controversy on the subject? But the Fathers chose and selected these words as the most obvious and natural.

Ib. s. xi. p. 431.

It is much insisted upou that it be inquired whether, when we say we believe Christ's body to be really in the Sacrament, we mean 'that body, that flesh, that was born of the Virgin Mary, that was crucified, dead, and buried?' I answer, that I know none else that he had or hath: there is but one body of Christ natural and glorified.

This may be true, or at least intelligible, of Christ's humanity or personal identity as

If a re-union of the Lutheran and English Churches with the Roman were desirable and practicable, the best way,

Ib. s. in. p. 434.

The other Schoolman I am to reckon in this account, is Gabriel Biel.

Taylor should have informed the reader that Gabriel Biel is but the echo of Occam, and that both were ante-Lutheran Protestants in heart, and as far as they dared, in word likewise.

Ib. s. vi. p. 436.

So that if, according to the Casuists, especially of the Jesuits' order, it be lawful to follow the opinion of any one probable doctor, here we have five good men and true, besides Occam, Bassolis, and Mechior Camus, to acquit us from our search after this question in Scripture.

Taylor might have added Erasmus, who, in one of his letters, speaking of Œcolampadius's writings on the Eucharist, says "ut seduci posse videantur etiam electi," and adds, that he should have embraced his interpretations, "nisi obstaret consensus Ecclesiæ;" that is, Œcolampadius has convinced me, and I should avow my conviction, but for motives of personal prudence and regard for the public peace.

Of the Sixth Chapter of St. John's Gospel

Ib. p. 436.

I cannot but think that the same mysterious truth, whatever it be, is referred to in the Eucharist and in this chapter of St. John; and I wonder that Taylor, who makes the Eucharist a spiritual sumption of Christ, should object to it. A = C and B = C, therefore A = B.73

Ib. s. iv. p. 440.

The error on both sides, Roman and Protestant, originates in the confusion of sign or figure with symbol, which latter is always an essential part of that, of the whole of which it is the representative. Not seeing this, and therefore seeing no medium between the whole thing and the mere metaphor of the thing, the Romanists took the former or positive pole of the error, the Protestants the latter or negative pole. The Eucharist is a symbolic, or solemnizing and totum in parte acting of an act, which in a true member of Christ's body is supposed to be perpetual. Thus the husband and wife exercise the duties of their marriage contract of love, protection, obedience, and the like, all the year long, and yet solemnize it by a more deliberate and reflecting act of the same love on the anniversary of their marriage.

Ib. s. ix p. 447-8.

That which neither can feel or be felt, see or be seen, move or be moved, change or be changed, neither do or suffer corporally, cannot certainly be eaten corporally; but so they affirm concerning the body of our blessed Lord; it cannot do or suffer corporally in the Sacrament, therefore it cannot be eaten corporally, any more than a man can chew a spirit, or eat a meditation, or swallow a syllogism into his belly.

Absurd as the doctrine of Transubstantiation may thus be made, yet Taylor here evidently confounds a spirit, ens realissimum, with a mere notion or ens logicum. On this ground of the spirituality of all powers

Ib. p. 448.

Besides this, I say this corporal union of our bodies to the body of God incarnate, which these great and witty dreamers dream of, would make man to be God.

But yet not God, nor absolutely. I am in my Father, even so ye are in me.

Ib. s. xxii. p. 456.

By this time I hope I may conclude, that Transubstantiation is not taught by our blessed Lord in the sixth chapter of St. John: Johannes de tertia et Eucharistica cæna nihil quidem scribit, eo quod cæteri tres Evangelistæ ante ilium eam plene descripsissent. They are the words of Stapleton and are good evidence against them.

I cannot satisfy my mind with this reason, though the one commonly assigned both before and since Stapleton: and yet ignorant, when, why, and for whom John wrote his Gospel, I cannot substitute a better or more probable one. That John believed the command of the Eucharist to have ceased with the destruction of the Jewish state, and the obligation of the cup of blessing among the Jews, – or that he wrote it for the Greeks, unacquainted with the Jewish custom, – would be not improbable, did we not know that the Eastern Church, that of Ephesus included, not only continued this Sacrament, but rivalled the Western Church in the superstition thereof.

Ib. s. i. p. 503.

Now I argue thus: if we eat Christ's natural body, we eat it either naturally or spiritually: if it be eaten only spiritually, then it is spiritually digested, &c.

What an absurdity in the word 'it' in this passage and throughout!

Vol. X. s. iii. p. 3.

The accidents, proper to a substance, are for the manifestation, a notice of the substance, not of themselves; for as the man feels, but the means by which he feels is the sensitive faculty, so that which is felt, is the substance, and the means by which it is felt is the accident.

This is the language of common sense, rightly so called, that is, truth without regard or reference to error; thus only differing from the language of genuine philosophy, which is truth intentionally guarded against error. But then in order to have supported it against an acute antagonist, Taylor must, I suspect, have renounced his Gassendis and other Christian Epicuri. His antagonist would tell him; when a man strikes me with a stick, I feel the stick, and infer the man; but pari ratione, I feel the blow, and infer the stick; and this is tantamount to, – I feel, and by a mechanism of my thinking organ attribute causation to precedent or co-existent images; and this no less in states in which you call the images unreal, that is, in dreams, than when they are asserted by you to have an outward reality.