Полная версия

Полная версияThe Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

Ib. s. lxxxii. p. 52.

This paragraph, though very characteristic of the Author, is fitter for a comedy than for a grave discourse. It puts one in mind of the play – "More sacks in the mill! Heap, boys, heap!"

Ib. s. lxxxiv. p. 56.

Præposterum est (said Paulus the lawyer) ante nos locupletes dici quam acquisiverimus. We cannot be said to lose what we never had; and our fathers' goods were not to descend upon us, unless they were his at his death.

Take away from me the knowledge that he was my father, dear Bishop, and this will be true. But as it stands, the whole is, "says Paulus the Lawyer;" and, "Well said, Lawyer!" say I.

Ib. p. 57.

Which though it was natural, yet from Adam it began to be a curse; just as the motion of a serpent upon his belly, which was concreated with him, yet upon this story was changed into a malediction and an evil adjunct.

How? I should really like to understand this.

Ib. ch. vii. p. 73 in initio.

In this most eloquent treatise we may detect sundry logical lapses, sometimes in the statement, sometimes in the instances, and once or twice in the conclusions. But the main and pervading error lies in the treatment of the subject in genere by the forms and rules of conceptual logic; which deriving all its material from the senses, and borrowing its forms from the sense

Now Original Sin, that is, sin that has its origin in itself, or in the will of the sinner, but yet in a state or condition of the will not peculiar to the individual agent, but common to the human race, is an idea: and one diagnostic or contra-distinguishing mark appertaining to all ideas, is, that they are not adequately expressible by words. An idea can only be expressed (more correctly suggested) by two contradictory positions; as for example; the soul is all in every part; – nature is a sphere, the centre of which is everywhere, and its circumference no where, and the like.

Hence many of Bishop Taylor's objections, grounded on his expositions of the doctrine, prove nothing more than that the doctrine concerns an idea. But besides this, Taylor everywhere assumes the consequences of Original Sin as superinduced on a pre-existing nature, in no essential respect differing from our present nature; – for instance, on a material body, with its inherent appetites and its passivity to material agents; – in short, on an animal nature in man. But this very nature, as the antagonist of the spirit or supernatural principle in man, is in fact the Original Sin, – the product of the will indivisible from the act producing it; just as in pure geometry the mental construction is indivisible from the constructive act of the intuitive faculty. Original Sin, as the product, is a fact concerning which we know by the light of the idea itself, that it must originate in a self-determination of a will. That which we do not know is how it originates, and this we cannot explain; first, from the necessity of the subject, namely, the will; and secondly, because it is an idea, and all ideas are inconceivable. It is an idea, because it is not a conception.

Ib. s. ii. p. 74, 75.

And they are injurious to Christ, who think that from Adam we might have inherited immortality. Christ was the giver and preacher of it; he brought life and immortality to light through the gospel. It is a singular benefit given by God to mankind through Jesus Christ.

And none inherit it but those who are born of Christ; ergo, bad men and infidels are not immortal. Immortality is one thing, a happy immortality another. St. Paul meant the latter: Taylor either the former, or his words have no meaning at all; for no man ever thought or dreamed that we inherited heaven from Adam, but that as sons of Adam, that is, as men, we have souls that do not perish with the body. I often suspect that Taylor, in abditis fidei

Ib. s. vi. p. 77.

"Lest the tumultuous crowd throw the reason within us over bridge into the gulf of sin." What a vivid figure! It is enough to make any man set to work to read Chrysostom.

Ib.

– – peccantes mente sub una.

Note Prudentius's use of mente sub una for 'in one person.'

Ib. p. 78.

For even now we see, by a sad experience, that the afflicted and the miserable are not only apt to anger and envy, but have many more desires and more weaknesses, and consequently more aptnesses to sin in many instances than those who are less troubled. And this is that which was said by Arnobius; proni ad culpas, et ad libidinis varios appetitos vitio sumus infirmitatis ingenitæ.

No. Arnobius never said so good and wise a thing in his lifetime. His quoted words have no such profound meaning.

Ib. s. vii. p. 78.

That which remained was a reasonable soul, fitted for the actions of life and reason, but not of anything that was supernatural.

What Taylor calls reason I call understanding, and give the name reason to that which Taylor would have called spirit.

Ib. s. xii. p. 84.

And all that evil which is upon us, being not by any positive infliction, but by privative, or the taking away gifts, and blessings, and graces from us, which God, not having promised to give, was neither naturally, nor by covenant, obliged to give, – it is certain he could not be obliged to continue that to the sons of a sinning father, which to an innocent father he was not obliged to give.

Oh! certainly not, if hell were not attached to acts and omissions, which without these very graces it is morally impossible for men to avoid. Why will not Taylor speak out?

Ib. s. xiv. p. 85.

The doctrine of the ancient Fathers was that free will remained in us after the Fall.

Yea! as the locomotive faculty in a man in a strait waistcoat. Neither St. Augustine nor Calvin denied the remanence of the will in the fallen spirit; but they, and Luther as well as they, objected to the flattering epithet 'free' will. In the only Scriptural sense, as concerning the unregenerate, it is implied in the word will, and in this sense, therefore, it is superfluous and tautologic; and, in any other sense, it is the fruit and final end of Redemption, – the glorious liberty of the Gospel.

Ib. s. xvi. p. 92.

For my part I believe this only as certain, that nature alone cannot bring them to heaven, and that Adam left us in a state in which we could not hope for it.

This is likewise my belief, and that man must have had a Christ, even if Adam had continued in Paradise – if indeed the history of Adam be not a mythos; as, but for passages in St. Paul, we should most of us believe; the serpent speaking, the names of the trees, and so on; and the whole account of the creation in the first chapter of Genesis seems to me clearly to say: – "The literal fact you could not comprehend if it were related to you; but you may conceive of it as if it had taken place thus and thus."

Ib. s. 1. p. 166.

That in some things our nature is cross to the divine commandment, is not always imputable to us, because our natures were before the commandment.

This is what I most complain of in Jeremy Taylor's ethics; namely, that he constantly refers us to the deeds or phenomena in time, the effluents from the source, or like the species of Epicurus; while the corrupt nature is declared guiltless and irresponsible; and this too on the pretext that it was prior in time to the commandment, and therefore not against it. But time is no more predicable of eternal reason than of will; but not of will; for if a will be at all, it must be ens spirituale; and this is the first negative definition of spiritual – whatever having true being is not contemplable in the forms of time and space. Now the necessary consequence of Taylor's scheme is a conscience-worrying, casuistical, monkish work-holiness. Deeply do I feel the difficulty and danger that besets the opposite scheme; and never would I preach it, except under such provisos as would render it perfectly compatible with the positions previously established by Taylor in this chapter, s. xliv. p. 158. 'Lastly; the regenerate not only hath received the Spirit of God, but is wholly led by him,' &c.

Ib.

If this Treatise of Repentance contain Bishop Taylor's habitual and final convictions, I am persuaded that in some form or other he believed in a Purgatory. In fact, dreams and apparitions may have been the pretexts, and the immense addition of power and wealth which the belief entailed on the priesthood, may have been their motives for patronizing it; but the efficient cause of its reception by the churches is to be found in the preceding Judaic legality and monk-moral of the Church, according to which the fewer only could hope for the peace of heaven as their next immediate state. The holiness that sufficed for this would evince itself (it was believed) by the power of working miracles.

Ib. s. lii. p. 208.

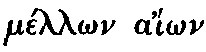

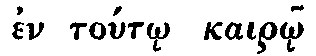

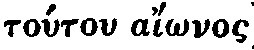

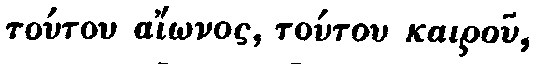

It shall not be pardoned in this world nor in the world to come; that is, neither to the Jews nor to the Gentiles. For sæculum hoc, this world, in Scripture, is the period of the Jews' synagogue, and

This is, I think, a great and grievous mistake. The Rabbis of best name divide into two or three periods, the difference being wholly in the words; for the dividers by three meant the same as those by two.

The first was the dies expectationis, or hoc sæculum,

But many Rabbis made the dies Messiæ part, that is, the consummation of this world, the conclusive Sabbath of the great week, in which they supposed the duration of the earth or world of the senses to be comprised; but all agreed that the dies, or thousand years, of the Messiah was a transitional state, during which the elect were gradually defecated of body, and ripened for the final or spiritual state.

During the millenium the will of God will be done on earth, no less, though in a lower glory, than it will be done hereafter in heaven.

Now it is to be carefully observed that the Jewish doctors or Rabbis (all such at least as remained unconverted) had no conception or belief of a suffering Messiah, or of a period after the birth of the Messiah, previous to the kingdom, and of course included in the time of expectation.

The appearance of the Messiah and his assumption of the throne of David were to be contemporaneous. The Christian doctrine of a suffering Messiah, or of Christ as the high priest and intercessor, has of course introduced a modification of the Jewish scheme.

But though there is a seeming discrepance in different texts in the first three Gospels, yet the Lord's Prayer appears to determine the question in favour of the elder and present Rabbinical belief; that is, it does not date the dies Messiae, or kingdom of the Lord, from his Incarnation, but from a second coming in power and glory, and hence we are taught to pray for it as an event yet future.

Nay, our Lord himself repeatedly speaks of the Son of Man in the third person, as yet to come. Assuredly our Lord ascended the throne and became a King on his final departure from his disciples. But it was the throne of his Father, and he an invisible King, the sovereign Providence to whom all power was committed.

And this celestial kingdom cannot be identified with that under which the divine will will be done on earth as it is in heaven; that is, when on this earth the Church militant shall be one in holiness with the triumphant Church.

The difficulties, I confess, are great; and for those who believe the first Gospel (and this in its present state) to have been composed by the Apostle Matthew, or at worst to be a literal and faithful translation from a Hebrew (Syro-Chaldaic) Gospel written by him, and who furthermore contend for its having been word by word dictated by an infallible Spirit, the necessary duty of reconciling the different passages in the first Gospel with each other, and with others in St. Luke's, is, me saltern judice, a most Herculean one.

The most consistent and rational scheme is, I am persuaded, that which is adopted in the Apocalypse. The new creation, commencing with our Lord's resurrection, and measured as the creation of this world (hujus sæculi,

But as the Jewish doctors made the day (or one thousand years) of Messiah, a part, because the consummation, of this world,

I have no objection; only you cannot pretend that this was the interpretation of the disciples. It may be the right, but it was not the Apostolic belief.

Ib. s. 1. p. 257.

For this was giving them pardon, by virtue of those words of Christ, Whose sins ye remit, they are remitted; that is, if ye, who are the stewards of my family, shall admit any one to the kingdom of Christ on earth, they shall be admitted to the participation of Christ's kingdom in heaven; and what ye bind here shall be bound there; that is, if they be unworthy to partake of Christ here, they shall be accounted unworthy to partake of Christ hereafter.

Then without such a gift of reading the hearts of men, as priests do not now pretend to, this text means almost nothing. A wicked shall not, but a good man shall, be admitted to heaven; for if you have with good reason rejected any one here, I will reject him hereafter, amounts to no more than the rejection or admission of men according to their moral fitness or unfitness, the truth or unsoundness of their faith and repentance. I rather think that the promise, like the miraculous insight which it implies, was given to the Apostles and first disciples exclusively, and that it referred almost wholly to the admission of professed converts to the Church of Christ.

In fine.

I have written but few marginal notes to this long Treatise, for the whole is to my feeling and apprehension so Romish, so anti-Pauline, so unctionless, that it makes my very heart as dry as the desert sands, when I read it. Instead of partial animadversions, I prescribe the chapter on the Law and the Gospel, in Luther's Table Talk, as the general antidote.68

Vindication of the Glory of the Divine Attributes

Ib. Obj. iv. p. 346.

But if Original Sin be not a sin properly, why are children baptized? And what benefit comes to them by Baptism? I answer, as much as they need, and are capable of.

The eloquent man has plucked just prickles enough out of the dogma of Original Sin to make a thick and ample crown of thorns for his opponents; and yet left enough to tear his own clothes off his back, and pierce through the leather jerkin of his closeliest wrought logic. In this answer to this objection he reminds me of the renowned squire, who first scratched out his eyes in a quickset hedge, and then leaped back and scratched them in again. So Jeremy Taylor first pulls out the very eyes of the doctrine, leaves it blind and blank, and then leaps back into it and scratches them in again, but with a most opulent squint that looks a hundred ways at once, and no one can tell which it really looks at.

Ib.

By Baptism children are made partakers of the Holy Ghost and of the grace of God; which I desire to be observed in opposition to the Pelagian heresy, who did suppose nature to be so perfect, that the grace of God was not necessary, and that by nature alone, they could go to heaven; which because I affirm to be impossible, and that Baptism is therefore necessary, because nature is insufficient and Baptism is the great channel of grace, &c.

What then of the poor heathens, that is, of five-sixths of all mankind. Would more go to hell by nature alone? If so: where is God's justice in Taylor's plan more than in Calvin's?

Ib. Obj. v. p. 355.

Although I have shewn the great excess and abundance of grace by Christ over the evil that did descend by Adam; yet the proportion and comparison lies in the main emanation of death from one, and life from the other.

Does Jeremy Taylor then believe that the sentence of death on Adam and his sons extended to the soul; that death was to be absolute cessation of being! Scarcely I hope. But if bodily only, where is the difference between ante and post Christum?

Ib. p. 356.

Not that God could be the author of a sin to any, but that he appointed the evil which is the consequent of sin, to be upon their heads who descended from the sinner.

Rare justice! and this too in a tract written to rescue God's justice from the Supra- and Sub-lapsarians! How quickly would Taylor have detected in an adversary the absurd realization contained in this and the following passages of the abstract notion, sin, from the sinner: as if sin were any thing but a man sinning, or a man who has sinned! As well might a sin committed in Sirius or the planet Saturn justify the infliction of conflagration on the earth and hell-fire on all its rational inhabitants. Sin! the word sin! for abstracted from the sinner it is no more: and if not abstracted from him, it remains separate from all others.

Ib. p. 358.

The consequent of this discourse must needs at least be this; that it is impossible that the greatest part of mankind should be left in the eternal bonds of hell by Adam; for then quite contrary to the discourse of the Apostle, there had been abundance of sin, but a scarcity of grace.

And yet Jeremy Taylor will not be called a Pelagian. Why? Because without grace superadded by Christ no man could be saved: that is, all men must go to hell, and this not for any sin, but from a calamity, the consequences of another man's sin, of which they were even ignorant. God would not condemn them the sons of Adam for sin, but only inflicted on them an evil, the necessary effect of which was that they should all troop to the devil! And this is Jeremy Taylor's defence of God's justice! The truth is Taylor was a Pelagian, believed that without Christ thousands, Jews and heathens, lived wisely and holily, and went to heaven; but this he did not dare say out, probably not even to himself; and hence it is that he flounders backward and forward, now upping and now downing.

In truth, this eloquent Treatise may be compared to a statue of Janus, with one face fixed on certain opponents, full of life and force, a witty scorn on the lip, a brow at once bright and weighty with satisfying reason: the other looking at the something instead of that which had been confuted, maimed, noseless, and weather-bitten into a sort of visionary confusion and indistinctness.69 It looks like this – aye and very like that – but how like it is, too, such another thing!

An Answer To A Letter Written By The Right Rev. The Lord Bishop Of Rochester, Concerning The Chapter Of Original Sin, In The "Unum Necessarium."

Ib. p. 367.

And they who are born eunuchs should be less infected by Adam's pollution, by having less of concupiscence in the great instance of desires.

The fact happens to be false: and then the vulgarity, most unworthy of our dear Jeremy Taylor, of taking the mode of the manifestation of the disobedience of the will to the reason, for the disobedience itself. St. James would have taught him that he who offendeth against one, offendeth against all; and that there is some truth in the Stoic paradox that all crimes are equal. Equal is indeed a false phrase; and therein consists the paradox, which in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred is the same as the falsehood. The truth is they are all the same in kind; but unequal in degree. They are all alike, though not equally, against the conscience.

Ib. p. 369.

So that there is no necessity of a third place; but it concludes only that in the state of separation from God's presence there is great variety of degrees and kinds of evil, and every one is not the extreme.

What is this? If hell be a state, and not a mere place, and a particular state, its meaning must in common sense be a state of the worst sort. If then there be a mere pæna damni, that is, the not being so blest as some others may be; this is a different state in genere from the pæna sensus: ergo, not hell; ergo rather a third state; or else heaven. For every angel must be in it, than whom another angel is happier; that is negatively damned, though positively very happy.

Ib. p. 370-1.

Just so it is in infants: hell was not made for man, but for devils; and therefore it must be something besides mere nature that can bear any man thither: mere nature goes neither to heaven or hell.

And how came the devils there? If it be hard to explain how Adam fell; how much more hard to solve how purely spiritual beings could fall? And nature! What? so much of nature, and no kind of attempt at a definition of the word? Pray what is nature?

Ib. p. 371.

I do not say that we, by that sin (original) deserved that death, neither can death be properly a punishment of us, till we superadd some evil of our own; yet Adam's sin deserved it, so that it was justly left to fall upon us, we, as a consequent and punishment of his sin, being reduced to our natural portion.