Полная версия:

Indo-European ornamental complexes and their analogs in the cultures of Eurasia

And, finally, almost any, the most complex and whimsical branched swastika pattern, we can easily find among the samples of weaving and embroidery of Vologda peasant women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It could be assumed that all these ornamental motifs came from Byzantium into facial embroidery, which adorns religious objects associated with Christian rituals and from it to peasant embroidery and weaving. But there are no such compositions in the Byzantine tradition, which is clearly evidenced by the samples of ornaments published by V.V. Stasov in the album “Slavic and Oriental Ornament Based on the Manuscripts of Ancient and Modern Times”. And at the same time, in medieval psalters, gospels, books of hours, etc. Russia, Armenia, Serbia, Croatia, many elements of Andronovo and Koban decor is constantly present, and, in particular, such characteristic motifs as swastikas of various configurations, jibs, meanders, triangles. They are found to this day in folk ornamentation in the North and Central Caucasus, on the western coast of the Caspian Sea, in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

It could be assumed that all these ornamental motifs came from Byzantium into facial embroidery, which adorns religious objects associated with Christian rituals and from it to peasant embroidery and weaving. But there are no such compositions in the Byzantine tradition, which is clearly evidenced by the samples of ornaments published by V.V. Stasov in the album “Slavic and Oriental Ornament Based on the Manuscripts of Ancient and Modern Times”. And at the same time, in medieval psalters, gospels, books of hours, etc. Russia, Armenia, Serbia, Croatia, many elements of Andronovo and Koban decor is constantly present, and, in particular, such characteristic motifs as swastikas of various configurations, jibs, meanders, triangles. They are found to this day in folk ornamentation in the North and Central Caucasus, on the western coast of the Caspian Sea, in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

In practice, the spread of the Andronovo circle ornaments is one of the most important indicators of the ways of promoting the agricultural and cattle breeding tribes of Eastern Europe in the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. So M. N. Pogrebova notes that white-encrusted ceramics, the striking similarity of which with the cut ornament of the Andronov culture has been repeatedly drawn by researchers, appears in the Eastern Transcaucasia in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC “in its current form with very rich and varied motives. She believes that in the addition of the Iranian material culture itself, newcomers from the steppes and forest-steppes of Eastern Europe played, apparently a significant role, as evidenced by archaeological sites of the early 1st millennium BC and, in particular, ceramics from Iran showing Andronovo influence, decorated with triangles and meanders, the meander being the leading ornamental motif (Tables 2, 3).

In practice, the spread of the Andronovo circle ornaments is one of the most important indicators of the ways of promoting the agricultural and cattle breeding tribes of Eastern Europe in the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. So M. N. Pogrebova notes that white-encrusted ceramics, the striking similarity of which with the cut ornament of the Andronov culture has been repeatedly drawn by researchers, appears in the Eastern Transcaucasia in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC “in its current form with very rich and varied motives. She believes that in the addition of the Iranian material culture itself, newcomers from the steppes and forest-steppes of Eastern Europe played, apparently a significant role, as evidenced by archaeological sites of the early 1st millennium BC and, in particular, ceramics from Iran showing Andronovo influence, decorated with triangles and meanders, the meander being the leading ornamental motif (Tables 2, 3).

A similar picture can be traced in the ornamentation of Central Asia in the late 2nd – early 1st millennium BC. M.A. Itina, on the basis of studying the materials of the Khorezm exposition, concluded that complex ethnocultural processes took place here in the Bronze Age. The steppe bronze culture discovered in the South Aral region on the territory of the Akcha-Darya delta of the Amu-Darya, named by S. P. Tolstov as Tazabagyab, and has stucco ware with geometric Andronovo type ornaments. M.A. Itina writes: “The presence of the Timber and Andronovo features in the Tazabagyab culture gives us grounds to speculate about the alien character of the Tazabagyab population of Khorezm.”

She also notes that the similarity of the ceramic material of the Bronze Age from the steppes of the Middle Volga region and Western Kazakhstan with Khorezm was more than once written by I. V. Sinicin. M.A. Itina believes that not only archaeological material makes it possible to record the advancement of pastoralist tribes from the northwest along the channels of the Uzboy, Atrek, Tejen, Murgab, Amu-Darya, Syr-Darya rivers, but also anthropological data record “a broad advance of the so-called Andronovo type to the south”. She subscribes to the opinion of S. P. Tolstov that the tribes of the Tazabagyab culture were “the first significant wave of Indo-European, Indo-Iranian or Iranian tribes that penetrated into Khorezm from the northwest”. I. M. Dyakonov believes that the path of the Aryan tribes from their ancestral home ran along the foothills of the Kopet-Dag, where there is “an ecologically uniform strip connecting Hindustan and the interior regions of Iran with Central Asia”. The same conclusion about the advance to the territory of Central Asia and further to Afghanistan and India of the northwestern pastoralist and agricultural tribes in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC does also V. I. Sarianidi. He notes that defensive fortresses with powerful walls and angular towers appear almost simultaneously in the Murghab basin (Auchin, Gonur), southern Uzbekistan (Sapali-Tepe), northern Afghanistan (Dashly I), “which excludes the element of chance and, on the contrary, acquires the features patterns due to the resettlement of tribes with general cultural unity”.

V. I. Sarianidi compares the seals-amulets of Murghab (Southern Turkmenistan) of the middle of the 2nd millennium BC with the Near East and concludes about their independent origin. Speaking about the ornamental motif in the form of a swastika (“viper knot”), characteristic of Murghab seals, he comes to the following conclusion: " It seems that this specific drawing is more inherent in Iranian than Mesopotamian art: in this case, the Murghab image… most likely of Iranian origin,” and “only in the Iranian world do we meet scenes approaching the drawings of the Murghab seals”. We, in turn, can add to the above that K. Humbert in his album of 1000 ornaments of various peoples of the world defines the braid in the form of a “viper knot” as characteristic of the Iranian and Indian traditions.

But such an ornamental motif is often found in the decor of medieval miniatures of Russia, as evidenced by the materials of V. V. Stasov’s album, for example, the headpiece of the Gospel 1409 of the Pskov work (Table 14), the miniature of the Psalter of the Konevsky Monastery, made in the 14th century in Novgorod (Table.15), a sample of ornaments from Ryazan, Galich, Vologda 14—16th century. In addition, the “viper knot”, which was so characteristic of the Iranian tradition of the mid-to-late 2nd millennium BC, is present in the embroideries of various provinces of Russia until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It decorates, as the main ornamental motif, a fly of the 17th century, embroidered spacers of the late 19th century in the Tambov and Voronezh provinces and Kirillovsky district of Novgorod province.

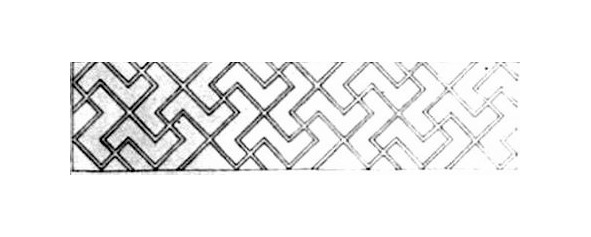

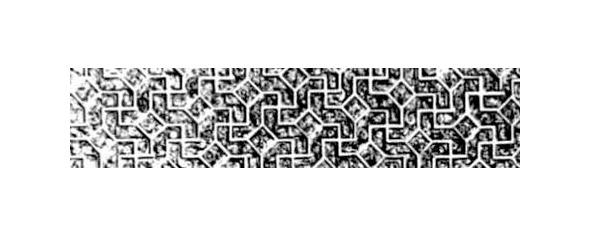

V. I. Sarianidi notes that with the spread of new types of seals, the practice of making anthropomorphic sculptures completely ceases in southern Turkmenistan and the Indus Valley, which indicates changes in the ideological ideas of the local population, and that many authors see new Indo-European tribes in the carriers of the Dzhukar culture Indian subcontinent. This is how R. Heine-Geldern and V. Ferservice identify the Djukarts with the Arias, and G. M. Bongard-Levin believes that: " the emergence of the Djukar reflects the penetration of a small group of tribes associated with Baluchistan into Sindh”. One of the most important proofs of the Aryan invasion is considered the seals from the Chankhu-Daro hill, which are sharply different from the Harappan seals proper and have analogues only in the Indus Valley, Southern Turkmenistan, Northern Afghanistan, Susiana. Of exceptional interest in the light of our problems is the discovery by the Soviet-Afghan expedition (under the leadership of V. I. Sarianidi) in Northwestern Afghanistan, northwest of Balkh, of a monumental complex, defined by V. I. Sarianidi as a “temple city” of the Bronze Age. K. Yettmar suggests that both the circular fortification with nine towers and the surrounding buildings Dashly 3, subordinated to a certain religious idea, were used only during the annual holiday period. He notes that memories of such ritual centers are preserved in both ancient Indian and ancient Iranian texts. In addition, the mythology of Nuristanis (Kafirs of the Hindu Kush) contains indications of the “heavenly castle” where the souls of the dead find shelter. Descriptions of such a castle are in many ways reminiscent of structures in northern Afghanistan. K. Yettmar believes that the analogies of the “temple city” of Dashly 3 in the steppe zone were Koy-Krylgan-Kalu and the Arzhan mound in Tuva. E. V. Antonova, analyzing the layout of the structures of Dashly 3 and Sappalli-Tepe (Southern Uzbekistan) and noting the presence of geometric shapes in their outlines, he writes: “The fact that the planning of structures was given special importance is also evidenced by the amazing closeness of the plans of several buildings of the Late Bronze Age with ornamental motives”. V. I. Sarianidi notes the unusual layout of the so-called “palace” Dashly-3 and considers the T-shaped, extremely narrow corridors, in which it is difficult for even one person to pass, very indicative. “It seems that they had a” false “character, did not carry any functional load, were the architectural and ritual canon that should have been unswervingly present in monumental buildings of this purpose”. We can state that the plan of the “palace” Dashly-3 (Table 16) is traditional, one of the most widespread, along with the swastika, elements of Russian weaving, the so-called. “rhombus with hooks”, the semantics of which is devoted to one of the works of A. K. Ambroz.

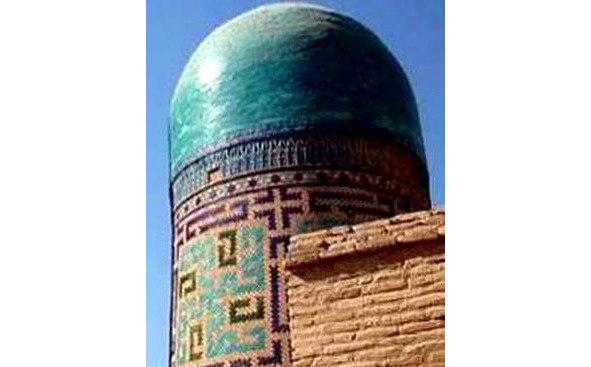

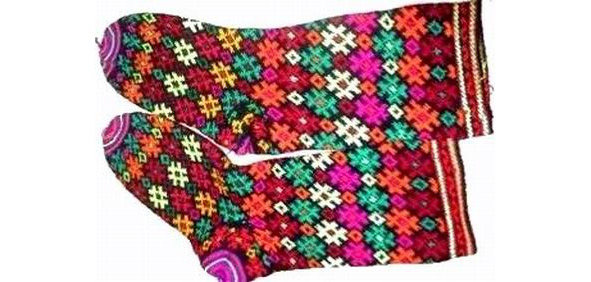

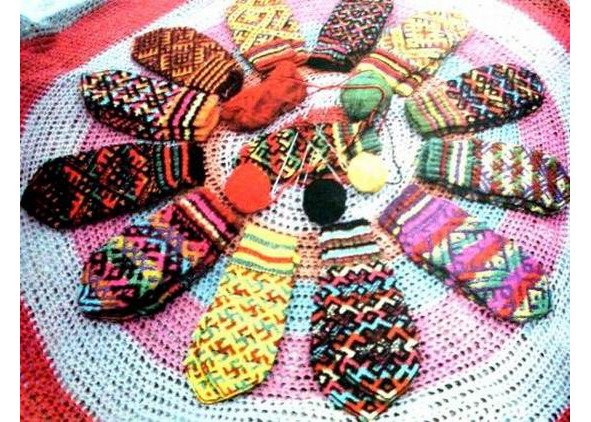

In Dashly-3, the “rhombus with hooks” is supplemented by T-shaped processes on the sides of the rhombus, which are also often found in rhombic compositions of North Russian ornamentation (Table 16). E. V. Antonova notes that the plan for the construction of the central part of Sapalli-Tepe becomes similar to the swastika. But such a swastika also has analogues in weaving and embroidery of the Vologda peasant women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As noted earlier, most researchers associate the appearance of ornaments of the Andronovo complex, and in particular, meanders, swastikas, etc., in Central Asia, Afghanistan and Hindustan in the late 2nd – early 1st millennium BC with the advance of the Aryan groups to these territories from the northwest. About how significant these ethnic shifts were, and what a serious change in ideological ideas they brought with them, is evidenced to a large extent by the fact that many of the archaic ornaments brought to Central Asia, Afghanistan, Hindustan by the northern steppe tribes, survived in this region to our time. So M. Ruziev in his work dedicated to Tajik woodcarving, writes, that in the design of the doors and gates of Bukhara, an important role is played by the geometric ornament that took shape in the pre-Muslim period, consisting of zigzags, rhombuses, squares, swastikas. Moreover, he attributes the swastika to the most ancient and stable motives of a geometric pattern. “It is found in various types of decorative arts – tiled decoration, paintings, embroidery, carpets… In Central Asia, this ornamental motif can also be found on knitted Pamir stockings, in carving on tombstones, carving and painting on ganch and wood, and glazed architectural ceramics. The swastika figured in the decoration of the brick floors of ancient Khuttal and on the ganch panels of the palace from Afrasiab (10—11 century).

Ganch panels of the palace from Afrasiab

Bukhara carved doors

On the carved doors of Bukhara dwellings, it often appears not only as an ornamental motive, but the door frame was also constructed from it…”

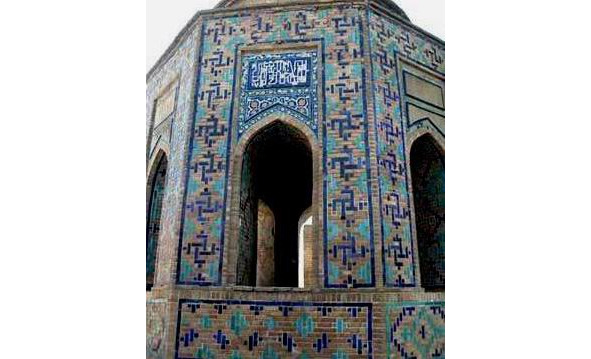

Shahi-Zind

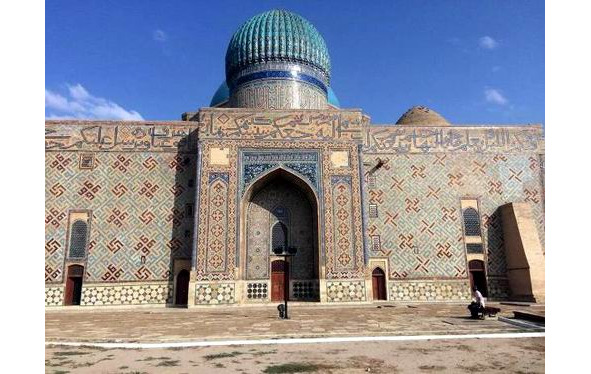

Bibi-Khanum

It should be remembered that the swastika is present in the decor of Shahi-Zinda (14th century), Bibi-Khanum (14th century), El-Registan (15—17th century) in Samarkand.

Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi. Turkestan.

The ancient traditions of Aryan ornamentation were especially stable in the art and architecture of the Pamiris, where they survived to this day, which was facilitated by the disunity and inaccessibility of mountain villages, a patriarchal way of life and the fact that for more than two millennia the population here did not practically change.

Pamir stockings and socks

Mezen mittens (Leshukonye village)

The common origins of both the East Slavic, in particular the North Russian, and the Mountain Tajik (i.e., East Iranian) ornamental tradition are evidenced not only by works of applied art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but also by archaeological materials; so, for example, intricately drawn swastikas on a clay carved mazar Mavlono Muhammad-Ali 10—12 century find an analogy in the drawing of a stamp on the bottom of a vessel from the 11th-12th century from Staraya Ryazan.

As for such archaic, dating back to Andronovo, ornaments on the other side of the Pamirs, on the territory of Hindustan, it is well known what a huge role the swastika plays in the rituals, ceremonies, and decor of India – a symbol of the sun, eternity, and happiness. M. Ruziev, noting that the Central Asian swastika compositions are related to the ancient Indian ones, focuses on the ancient tradition, following which on the day of the Yatra holiday, the brahmans in desert places arranged large sacrificial fires, each of which consisted of four swastikas.

It must be said that such compositions of four swastikas, grouped around a common center, are characteristic not only of ancient Indian, but also of both the South Russian (Tambov, Voronezh, Kursk, Ryazan) and North Russian traditions.

Moreover, in Vologda typesetting weaving and embroidery, combining swastikas into groups of four is one of the most common techniques, as evidenced by such materials from the Vologda Regional Museum, as the 19th century Veliky Ustyug fly embroidered with white thread (Table 17), typesetting spacers of the middle and second half of the 19th century (Table 18), luxurious, almost half-meter typesetting end, towels made in the second half of the 19th century by the Tarnog peasant woman Akulina Yermolina (Table 19), homespun tablecloth decor of the late 19th century, etc. (Tables 20, 21). And, finally, E. E. Kuzmina, noting that home pottery is one of the defining features in traditional cultures and the most important ethnic determinant, writes that, starting from the Neolithic and up to the Iron Age in the steppe, in contrast to Central Asian agricultural centers, not painted, but stamped geometric ornament dominated. She believes that: “the pottery of the Vedic Aryans was akin to the ceramic production of the Iranian-speaking peoples, and the origins of this common tradition can be traced not in the agricultural cultures of Iran and Western Asia, but in the pastoral cultures of the Eurasian steppes, primarily in the Andronovo”. This is all the more obvious that: “the analogies in the technique of Vedic pottery with Andronovo are so numerous and significant, and the technological methods are so specific that this gives grounds to associate the origin of the traditions of home pottery production of the ancestors of the Vedic Aryans with the carriers of the Andronov cultural community”. And although, as noted by E. E. Kuzmin, there is a difference in that the Andronovo ceramics are richly decorated, and there are few such ornaments on the Aryan ceramics of Hindustan, “the presence of a stamped ornament is noted in Vedic sources” and “all elements of the Andronovo ornamental complex are still preserved in the folk art of India”. Following E. E. Kuzmina, we state that all the elements of the Andronovo ornamental complex were preserved until the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century also in typesetting weaving and embroidery of North Russian (Vologda, Arkhangelsk) peasant women. E. E. Kuzmina writes: “A thorough analysis in terms of the tradition of the semantics of images of the fine arts, for which archeology already provides rich material, will apparently be of decisive importance in the study of the complex ethnic history of South Central Asia and Afghanistan.”

It seems that a comprehensive consideration of the development of ornaments common to the North Russian and Indo-Iranian traditions, from ancient times to the present day, testifies to the common, deeply archaic origins of these traditions, to the long process of development and transformation of the ancient archetype, to the joint development of more diverse, new ornamental patterns, about the huge genetic relationship of these peoples. Similar ornaments, of course, can occur among different peoples, but it is difficult to believe that people are separated by thousands of kilometers distances and millennia (unless they are ethnogenetically related), such complex ornamental compositions can appear completely independently of each other, repeating even in the smallest details, moreover, they perform the same sacred functions of amulets and signs of kinship.

Making a conclusion about the indisputable kinship of the archaic East Slavic and Indo-Iranian complexes, we must emphasize that, despite the significant diversity of these ornaments in the Indo-Iranian region, the most archaic types and their greatest diversity are characteristic of East Slavic, specifically North Russian folk art. It is here that practically all links of the millennial ornamental tradition have been preserved intact, starting with the Upper Paleolithic rhombo-meander motifs and up to the most complex Abashev, Pozdnyakov and Andronovo ornamental complexes.

All this allows us to conclude that it was on the territory of Eastern Europe that the most ancient geometric ornamental complexes were formed, which became sacred symbols of the Indo-Iranian peoples, on the one hand, and did not lose their sacred functions of amulets and signs of kinship among the East Slavic peoples, until the beginning of the 20th century, with another.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов