Полная версия:

Indo-European ornamental complexes and their analogs in the cultures of Eurasia

Ornament of Neolithic settlements of Ukraine

Comparing the Paleolithic bone objects decorated with this ornament with the Neolithic “seals”, he concludes that such stamps were made to tattoo a woman’s body during ritual acts, and that it is the custom of tattooing that is the connecting link that fills the Mesolithic gap between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. But along with the preservation of the ancient ornament in the form of mandatory ritual coloring in the Mesolithic, it can also be assumed that in the Neolithic period the seals were no longer used for tattooing or not only for it, but at some stage they began to apply carpet-meander patterns on fabrics made of plant fibers, which probably already existed in the Neolithic life, as evidenced by the finds of spinning wheels.

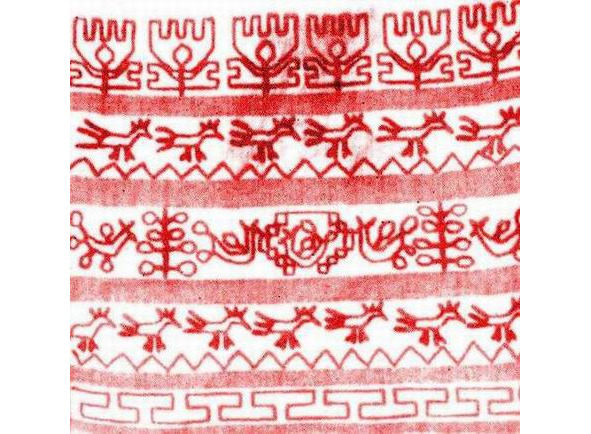

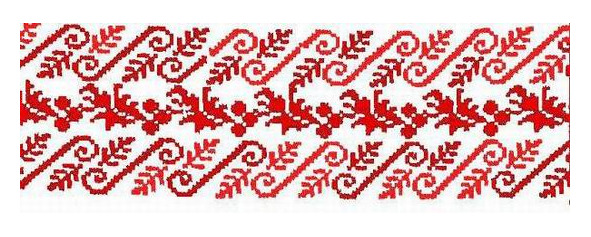

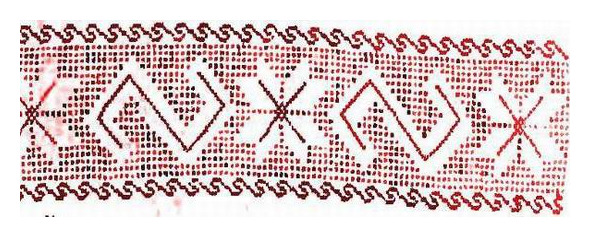

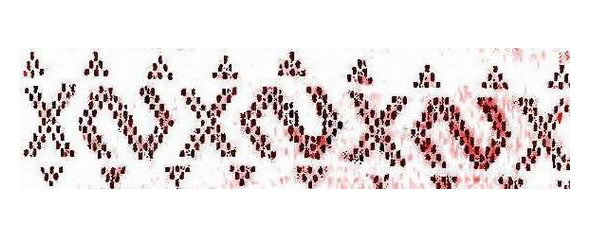

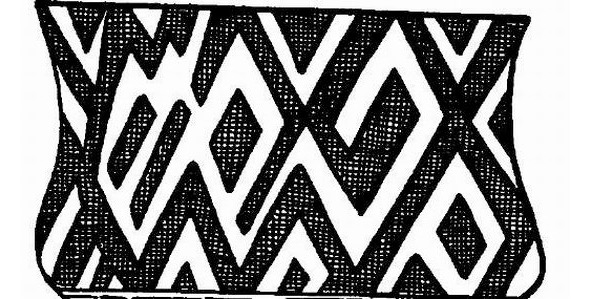

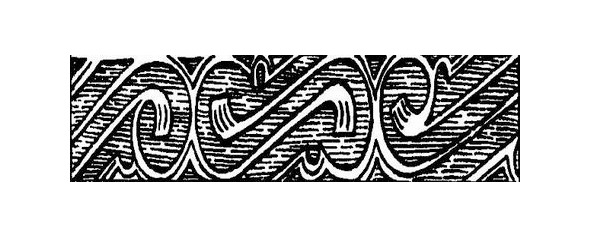

With the development of weaving techniques, the ancient craftswomen of the Neolithic or Eneolithic were able to transfer complex ornaments from rhombuses and meanders directly into the structure of the fabric. Such an ancient carpet-type ornament, almost identical to the Mezin and Early Neolithic, can be easily found on linen canvases that existed in North Russian villages at the beginning of the 20th century. Made in a multi-thread technique, they are all completely covered with a rhombo-meander pattern, obtained with a complex interweaving of warp and weft threads. As a rule, towels, tablecloths, skirts were made of such canvas, to which strips of spacers were sewn, recruited with red threads along a white field. The ornament of these spacers is often very similar to the ancient rhombo-meander, but while the texture of the white canvas repeats the ancient compositions with practically no changes, on the spacers we see, as it were, fragments of an archaic scheme, its parts divided and grouped according to some new principles.

North Russian weaving

Weaving Central Russia

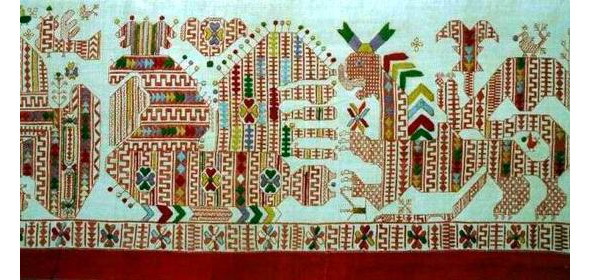

Ukrainian weaving

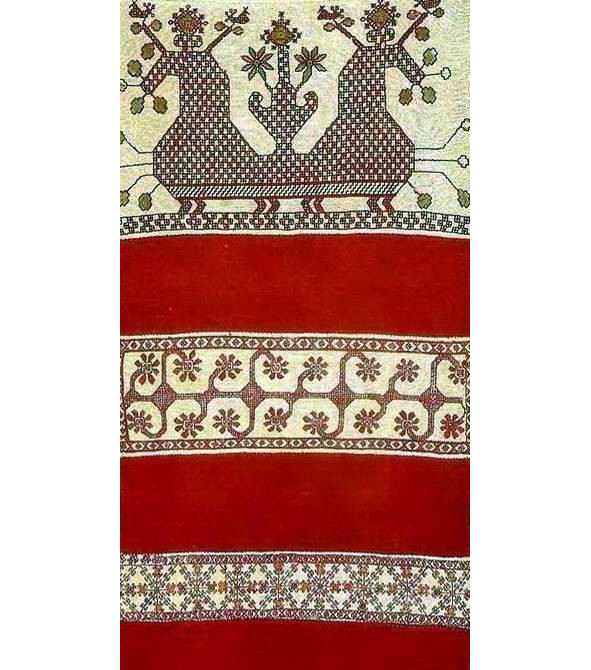

Weaving Hindustan

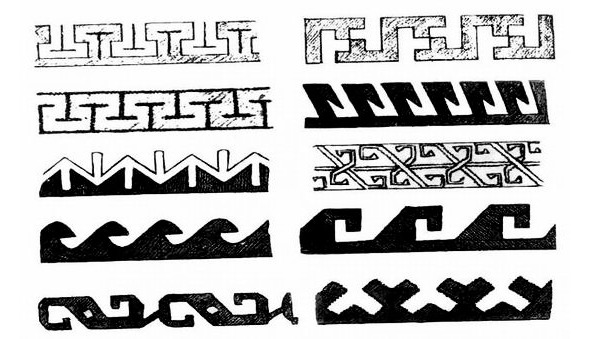

It must be said that the possibility of such variability was laid in the Mezinian ornaments. Despite the outward similarity, the ornaments of items from the Mezin site have a number of differences. So on the bracelet there is a carpet-meander pattern, but on the figurines from the mammoth tusk the pattern is already somewhat different: it is a meander spiral placed among zigzags, parallel meander stripes and a meander, depicted in motion from right to left and left to right, in which the outlines are already quite clearly read one of the most widespread signs during the Eneolithic and copper-bronze on the territory of Eastern Europe – the swastika (Table 4).

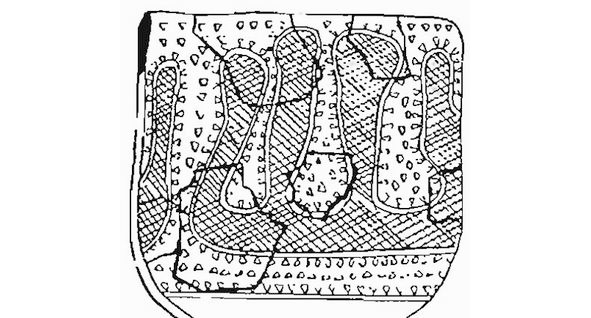

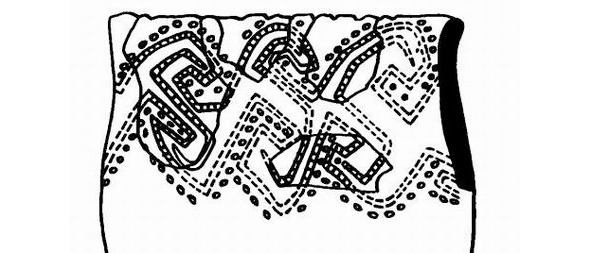

This ornamental differentiation becomes even more evident in the Neolithic. So a large number of different variants of ornaments based on the rhombo-meander Paleolithic composition give us Neolithic “seals” (on which one can find rows of S-shaped meander elements – “jibs”, and meander stripes, and swastika elements) and Neolithic clay statuettes depicting women, covered with all sorts of meander composition motifs. B. A. Rybakov notes that if the meander pattern was widely used in the Neolithic for ornamentation of ceramics in general, then “for ritual dishes and plastics, it was almost mandatory”.

There is an opinion in science that the geometric ornament was transferred to ceramics made of soft materials.

Agreeing with this, we can assume that, probably, the same ornaments were obligatory for clothing, at least for clothing that performs ritual and protective functions. We can assume that already on the border of the Neolithic and Eneolithic, marked by an even more vivid flourishing of geometric ornament in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, clothes were decorated with woven ornaments.

This is all the more likely, since “the second half of the 3rd thousand BC refers to the mass distribution of spinning, i.e. the intensive development of spinning, noted not only for Eastern Europe, especially for the Tripolye circle, but also for Asia Minor”. Naturally, we can only roughly imagine what the fabrics from which the clothes of the Eneolithic people were made, but as for the rhombo-meander pattern in its various modifications, its development and transformations at this time are very well illustrated by the ceramic products of the brightest culture of the Eastern Eneolithic and South-Eastern Europe – Tripoli-Cucuteni. B. A. Rybakov notes that in this culture: “The rhombo-meander ornament is found on dishes (especially on ritual, lavishly decorated vessels), on clay anthropomorphic figurines, too, undoubtedly ritual, on the clay thrones of goddesses and priestesses.” V. N. Danilenko, speaking of the fact that even in the early Neolithic in the territories later occupied by the Tripolye culture, meander compositions almost completely dominated, comes to the conclusion about the substrate nature of the meander ornament of the Tripillya dishes and its deep archaism, which numerous positive-negative compositions.

On the ceramics and cult sculpture of the Eneolithic, we find a steadily repeating scheme of the meander pattern, which already somewhat differs from the Upper Paleolithic Mezinian and Neolithic in its great geometrism and clarity of rhythm. This is evidenced by the decoration of ceramic products found in Moldavia in the settlements of Frumushika I, Hebeshesti, Gura Vey. The meander pattern adorns the sides of the Kernosovsky idol found in the Dnieper region: the central phallic image is, as it were, supplemented by side compositions, one of which is represented by a set of zigzag and meander stripes, on the other such zigzag and meander stripes rise above the fertilization scene and the image of a bull with moon-shaped horns under this scene. The whole complex of plots leaves no doubt about their sacred character. A. A. Formozov writes: “Sometimes ancient things have a magnificent pattern covered with areas hidden from the viewer’s eyes – the bottoms of vessels or the reverse side of the plaques sewn onto clothes. From an aesthetic point of view, this is meaningless”. A lot of such senseless from the point of view of aesthetics, but probably playing a huge ritual role of ornaments, we meet precisely on the bottoms of Tripolye vessels.

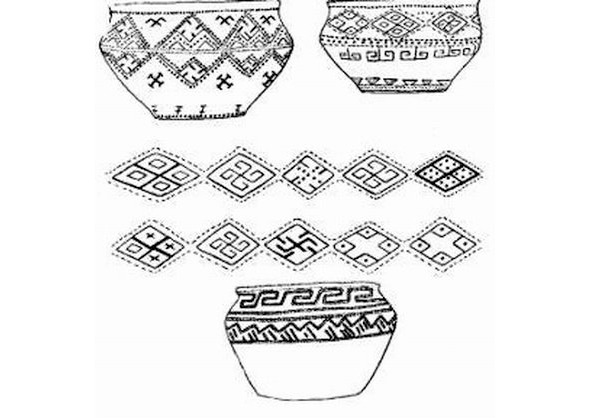

Tripolie ornament

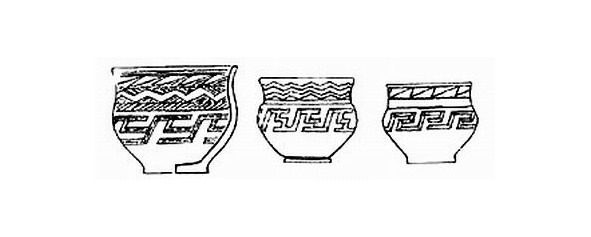

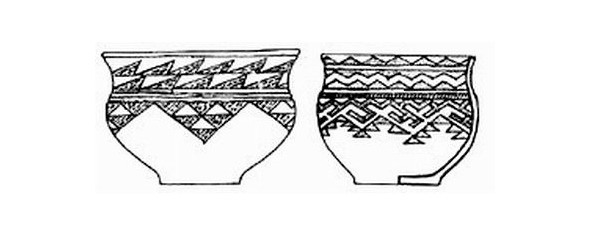

Ornament of Seroglazov ceramics (Neolithic)

Among these sacred signs, first of all, it is worth mentioning the meander spiral, the swastika used in its simplest version or complicated by new composite elements in the form of additional processes on each curved side of the cross, and the peculiar transformation of the meander motif, represented by the S-characteristic ceramic decor next to S- shaped “geese” (tab. 5). It must be said that throughout the history of Tripoli culture, in any case, at its early and middle stages, two main directions in the development of ceramic ornament can be distinguished.

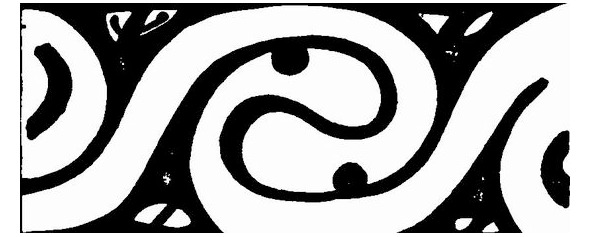

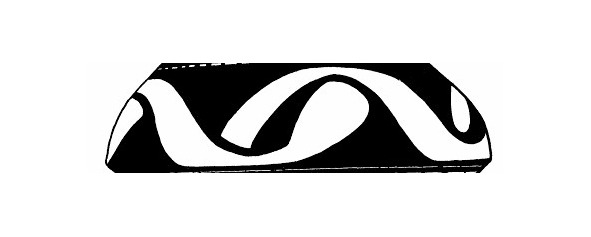

On the one hand, this is a geometric angular style, using various variations of the meander pattern and most clearly developing the archaic rhombus-meander ornament. On the other hand, this is a drawing of smooth, wilted forms, gravitating to a circle.

V. N. Danilenko writes that: “By the time of the spread of the most ancient painted utensils, the beginning of the bifurcation of the development paths of the Trypillian culture was an obvious fact,” but it manifested itself most vividly when in the eastern half of the Trypillian area – on the Middle Dnieper region, in the Bug region and partly in the Middle Dniester region in the ethno-historical process “a powerful eastern component was included – the early links of the ancient pit culture”. It was here that by the time of the beginning of the transformation (in the process of mutual influences) of both the Trypillian and Yamnaya cultures, which served as the basis for many cultures of the Bronze Age, that circle of ornamental motifs was formed, rather limited and not exhaustive, no doubt, of the entire richness of the Tripillian ceramics decor, but nevertheless less characteristic of this culture, with which materials of subsequent historical periods are to be compared in the future. This is a meander and its varieties: meander spiral, intricately drawn cross-swastika, S-shaped figures – “jibs”.

Ornament of Tripolie ceramics (Eneolithic)

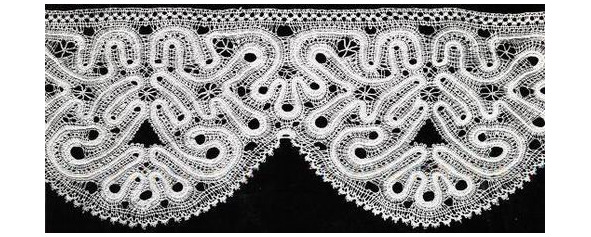

Vologda lace

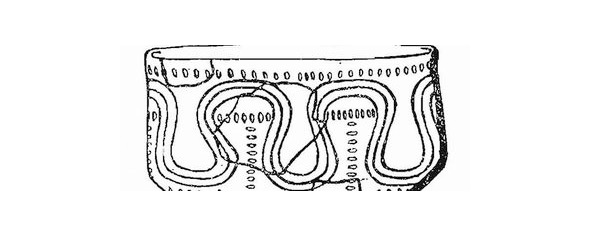

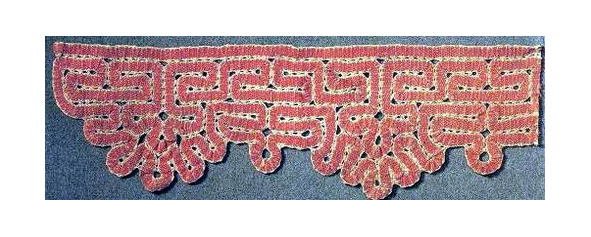

Before we turn to the materials of those cultures that replaced Trypillian and Yamnaya in the Bronze Age, i.e. to the Corded Ware cultures that emerged on the basis of the cultures of Corded Ware: Tshinetsko-Komarovskaya and Abashevskaya, Srubnaya and Andronovskaya, I would like to note that, paradoxically, many ornamental motifs characteristic of Tripillya and disappearing in subsequent genetically related Trypillian cultures survived until the 20th century no changes in the products of the North Russian peasant women. In this respect, the Vologda lace of the 19th century, or rather its peasant version, not designed for urban consumers, is of exceptional interest. In this form of folk art, a geometric layer coexisted at the same time – rhombuses, jibs, swastikas, meanders, and smooth, rounded meander combinations, almost absolutely identical to those of Tripoli.

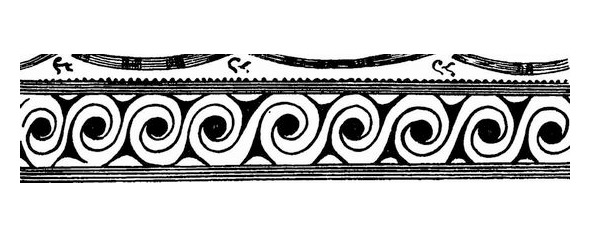

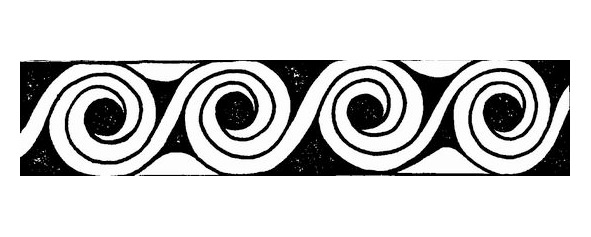

The basis of the ornament in such lace, which is performed to decorate the ends of towels and valances of wedding sheets, is a dense, up to 1 centimeter wide, ribbon, very often saturated red, which, whimsically wriggling, builds a pattern, and, above all, a meander pattern. It is interesting that such a decorative solution is typical only for North Russian, and in particular, for Vologda lace (Table 3).

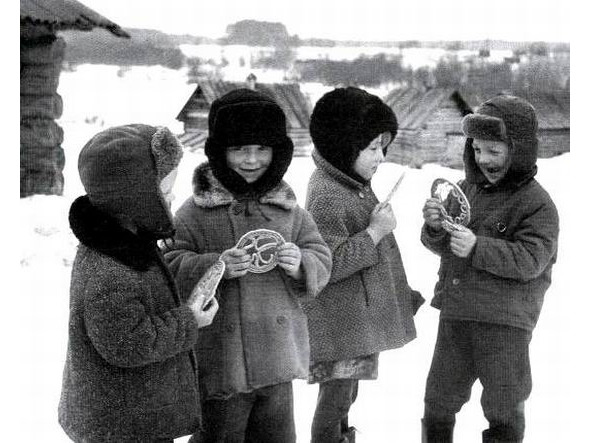

Kargopol gingerbread cookies 1977

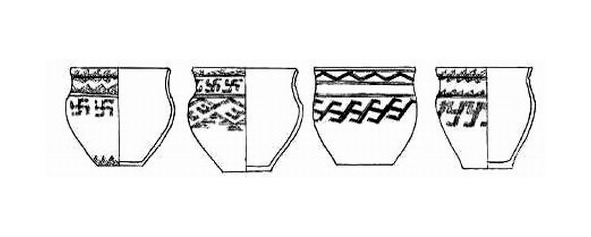

Returning to the monuments of the Bronze Age on the territory of Eastern Europe, I must say that in Trzyniecko-Komarovska; In the ornamental complex, many elements of Tripillya ornamentation are widespread. Thus, on a cult vessel from the village of Pereshchepino, various rhombuses, a meander stripe, a swastika are presented; on ceramics with drawings and signs from Bondarikha there are all kinds of swastika elements, and on items from Vladimirovka rhombuses, swastikas of various shapes, oblique crosses and “jibs” are constantly repeated (Table 6).

S. S. Berezanskaya connects this ornamentation with the ritual, ceremonial side of the life of people of the Bronze Age. She writes: “It is possible that signs placed on them outside the ornamental system (crosses, rosettes, circles, shaded triangles and rhombuses), which were used as various magic symbols, testify to the cult purpose of some vessels”. The researcher notes that on many vessels of the Srubna culture there are signs that are similar in appearance to runes, which have analogues on the obviously cult objects-spinning wheels, “horned spindle wheels” and miniature “vessels” of the Trzhinets, Belogrudov, Milograd and Bondarikha Proto-Slavic cultures. A. A. Formozov connects these signs, among which there are often oblique crosses, swastikas of various configurations, jibs, with the addition of the peoples of these cultures of writing, which arose on a local basis by schematizing the elements of ornament.

Not all researchers agree with such conclusions, but one thing is indisputable; from what we have today, we can nevertheless conclude that in the Slavic Trinecko-Komarov culture the same signs as in Tripoli – meander, rhombus, swastika, jibs – perform the same sacred functions of the sign – amulet or magic spell addressed to gods and spirits. Turning further to the ornamental complexes of the Abashev culture, we can note that here, as in the Tszynets-Komarska culture, and even to an even greater extent, the ornament consists of various meanders, swastikas and jibs. In contrast to the Abashevskaya, in the ornamental complexes of the Srubna culture, the motif of the meander and the intricately drawn cross is rather rare. The main component of the decoration of the Srubna culture ceramics (16—12 centuries BC according to B. Ch. Grakov) are chains of rhombuses, rhombic meshes and rows of triangles on the shoulders of vessels; the body is often decorated with characteristic oblique crosses, sometimes composed of two overlapping S-shaped forms.

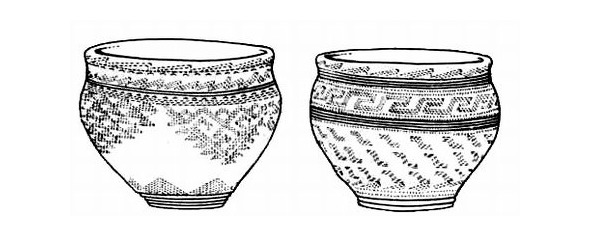

Ornament of archaeological log house culture

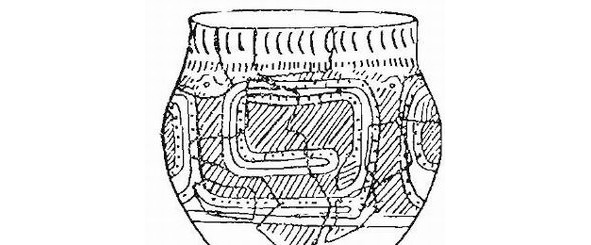

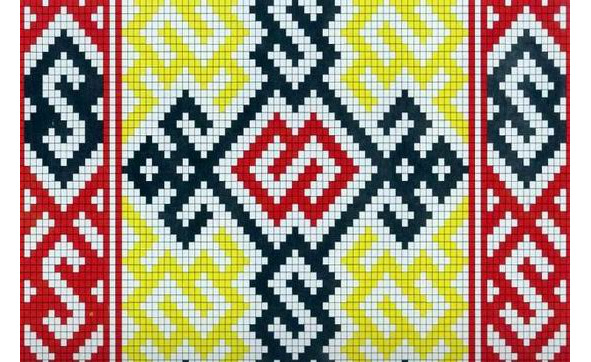

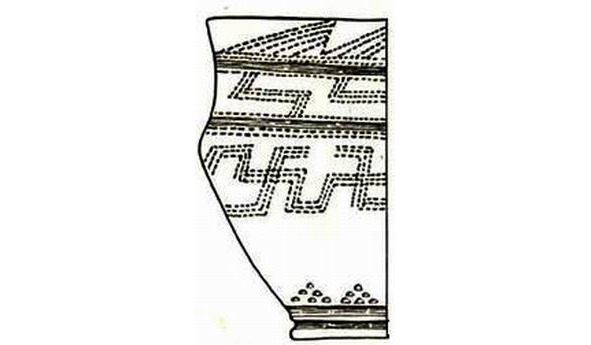

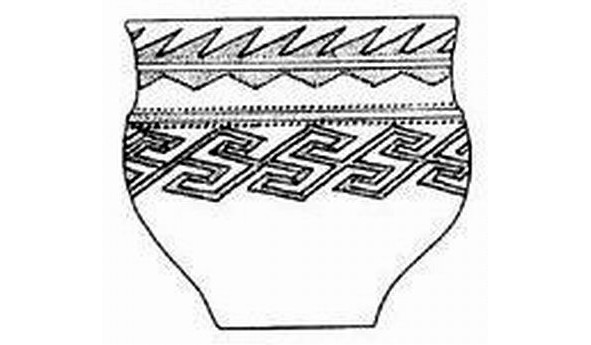

The development of ceramics ornamentation, which includes an amazing variety of different variants of meander and spastic motifs, we see among the closest neighbors of the “Srubniks” – the population of the Andronovo cultural community (17—9 century BC according to E. Ye. Kuzmina). Synchronous in time, these two cultures, as noted earlier, coexisted for a long period in very vast territories of the steppe and forest-steppe zones of our country, spreading in the north up to the Komi-Permyatskiy A.O. (middle course of the Kama River) in its Andronovo-Alakul variant.

In the south, the monuments of the Andronov community go to the deserts and semi-deserts of Central Asia and the highlands of the Tien Shan and Pamirs to the oases of Central South Asia and Afghanistan.

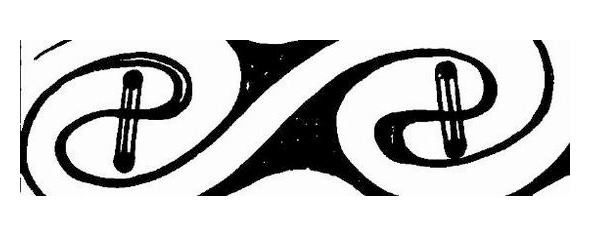

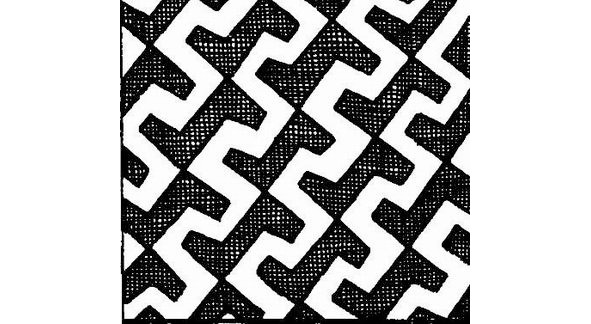

Pottery exhibiting the Andronovo influence was found during excavations in Iran (Tables 2, 3). In the east, the Andronovo culture reaches the Yenisei, and in the north-west, on the territory of Northern Sweden, in the 10—8th century BC. the ceramics of the Andronovo type with a characteristic meander pattern was widespread, which M. Stenberger associates with the Ural-Siberian cultural group. (It is interesting to note that this culture in Scandinavia is replaced by ceramics of the Ananyin appearance, which existed here from the 4th to the 2nd century BC, while the Ananyin culture in the Volga region develops from the 7th to the 2nd century BC). Noting the kinship of ceramic decor among the Timber and Andronovo tribes, S. Z. Kiselev wrote: “…One cannot fail to note the obvious superiority of even the early Andronovo ceramics over its related Timber.” It is impossible to disagree with this; the forms of the Andronovo decor are so rich and varied. The richly ornamented Andronovo crockery in its classic version is known mainly from burial grounds. In connection with this circumstance, M. F. Kosarev makes the following assumption: “Ornate dishes of the classical Andronovo style with rich geometric ornamentation are ritualistic and therefore were especially characteristic in burial grounds and sacrificial sites”. G. B. Zdanovich also believes that the magnificently ornamented dishes were ceremonial, cult. Speaking about ceramics typical for burials, he states that we have before us “a vivid manifestation of cultural traditionalism in the funeral rite”, while in everyday life new dishes have been used for a long time, dishes of old traditional forms are put in burials. “The latter is no longer used for everyday household and household needs, and the very fact of its existence is determined by ritual purposes”. But on the classical (ritual) Andronov dishes, we find the same set of ornamental motifs characteristic of ritual sculpture and vessels in Tripillya – meander, meander spiral, swastika, a number of jibs, etc. While retaining the archetype, they acquire a great variety. Speaking about the specificity of the ornamentation of this ceramics, S. V. Kiselev noted its deep originality, the zonality of the arrangement of various patterns, in which the place of one or another pattern in the zones is usually the same. He said that the complex forms of the Andronovo patterns “were quite likely to be realized with their conditional symbolism… their special meaning, symbolic meaning are emphasized by their special complexity”. M. D. Khlobystina expressed herself even more definitely: “There was, apparently, a kind of communal core, a collective bound by the norms of patriarchal disposition, which, in turn, had certain pictorial symbols of its tribal affiliation, encrypted for the researcher in a complex interweaving of geometric It can be assumed that a kind of leading element of such ornaments is a number of figures located on the shoulders of the vessel: study of the number and combination of these particular patterns, represented by S-shaped signs, meanders, segments of broken lines and their variations, maybe obviously play a role in clarifying the structure of each community.”

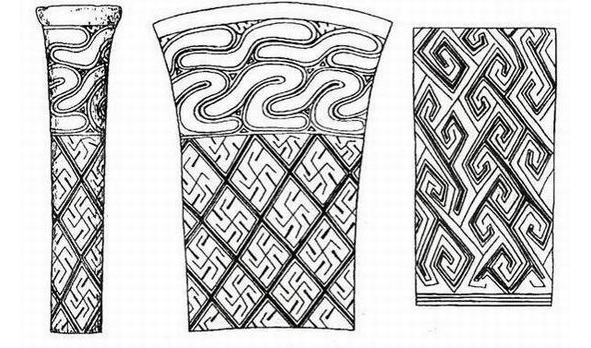

Ornament of Andronovo culture

Karasuk ornament

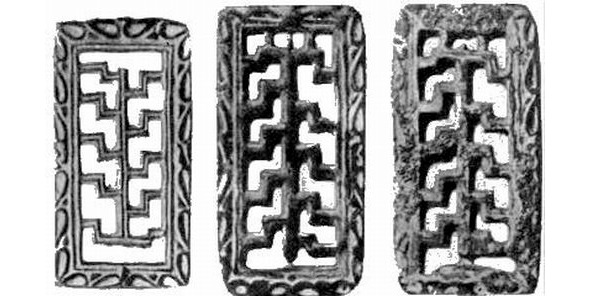

We share the point of view of those researchers who are convinced of the deeply significant content of the Andronovo ornament, consecrated by tradition: after all, it is no coincidence that vessels with just such a decor were placed in the graves, i.e. they probably really performed the functions of a clan or tribal sign, were a kind of “visiting card” in the journey of the deceased to their ancestors, who, by these ornamental “letters”, should have recognized a member of their clan, their tribe. In this sense, the ornament on Andronovo ceramics served as a talisman, protecting its owner on the way to another world or asking the gods for mercy. Thus, we can once again state that the carpet ornament of the Andronov crockery was probably a kind of sign, a symbol of the tribal and ethnic identity of a person whose things were decorated with this particular ornament. In this sense, it, apparently, was preserved in the Karasuk era (12—7 century BC), when the

“Scythian-Siberian animal style” was born, and in the Tagar time (7—1 century BC) BC), since along with the images of animals on the famous Minusinsk openwork belt plates, there is often an ornament typical for the decor of Andronov ceramics, in particular, a lattice of S-shaped elements. Common in the Middle Yenisei in the 3rd – 1st century BC, these plates are found on the territory of Ordos and Inner Mongolia, which was apparently associated with the migration of the population of the southern outskirts of the Western Siberian taiga and more southern and eastern ones that began at the turn of the Bronze and Iron Ages. Areas.

Tagar products

Thus, we can state that the traditional ornament, consisting of meander, swastika and S-shaped forms, characteristic of the decor of Andronov ceramics, existed on the territory of Western Siberia, in particular the Minusinsk Basin, up to the first centuries of our era. Some of these ornamental motifs reach Ordos and Inner Mongolia. In a relict, fragmentary form, many Andronovo compositions continued to live in the art of the peoples of Siberia up to the present day.

Returning to the European part of our country, in this particular case to the North Russian lands, we must say that, contrary to the prevailing belief in science so far, that the North Russian region is characterized, first of all, by plot compositions, both in embroidery and Even before the 20—30s of the 20th century, geometrically, ornament played a huge role in textile decoration. Moreover, on the branched spacers made by the hands of North Russian peasants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not individual elements of the Andronovo ornament, not its later transformations, were preserved, but whole ornamental complexes of the classic carpet pattern, the ritual nature of which was mentioned above. Such ornaments, designed in most cases in the ancient red-and-white color scheme, consisting of meanders, triangles, zigzags, rhombuses, swastikas, “jibs”, decorate the sleeves, hem and shoulder of women’s shirts, the edges of aprons, belts, ends of towels, etc. e. ritual, sacredly marked things that, in addition to purely everyday things, also performed magical and protective functions. As in the entire Andronovo ornament, in North Russian brane weaving, the composition is divided into three horizontal zones, with the upper and lower ones often duplicating each other, and the middle one, as a rule, bears the most important patterns from the point of view of Samantically significant. It is here that you can find the most diverse motifs of meander, “jibs”, swastikas, absolutely identical to Andronov’s, and their convergence is striking.