Полная версия:

The Lost Tommies

The process of identifying, at least by regiment, as many of the Thuillier images as possible for this book has been a painstaking and often frustrating process. Many of the soldiers were photographed in front of the distinctive painted canvas backdrop and that has been a useful fingerprint in identifying Thuillier pictures which made their way back home into family collections or regimental history books. On rare occasions the identification was easy because a particular soldier features and is actually named in one of the rare Thuillier images reproduced in regimental history books or contained in personal collections. There have been other occasions where photographs taken of soldiers after the war have allowed us to ‘match’ them with a soldier in a Thuillier image (see the Royal Fusiliers). Once identified, it has also been difficult to find out more about a particular soldier because so many of the British service files are incomplete or were destroyed completely in German bombing raids during the Second World War.

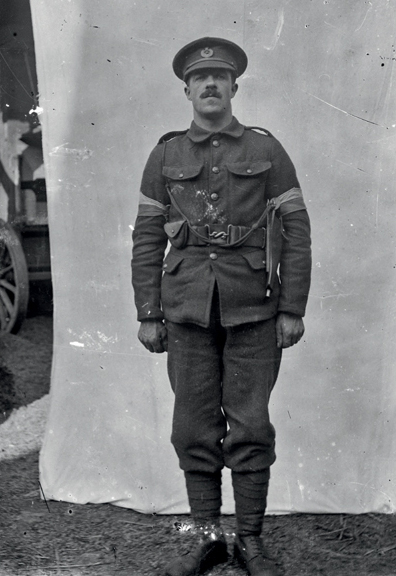

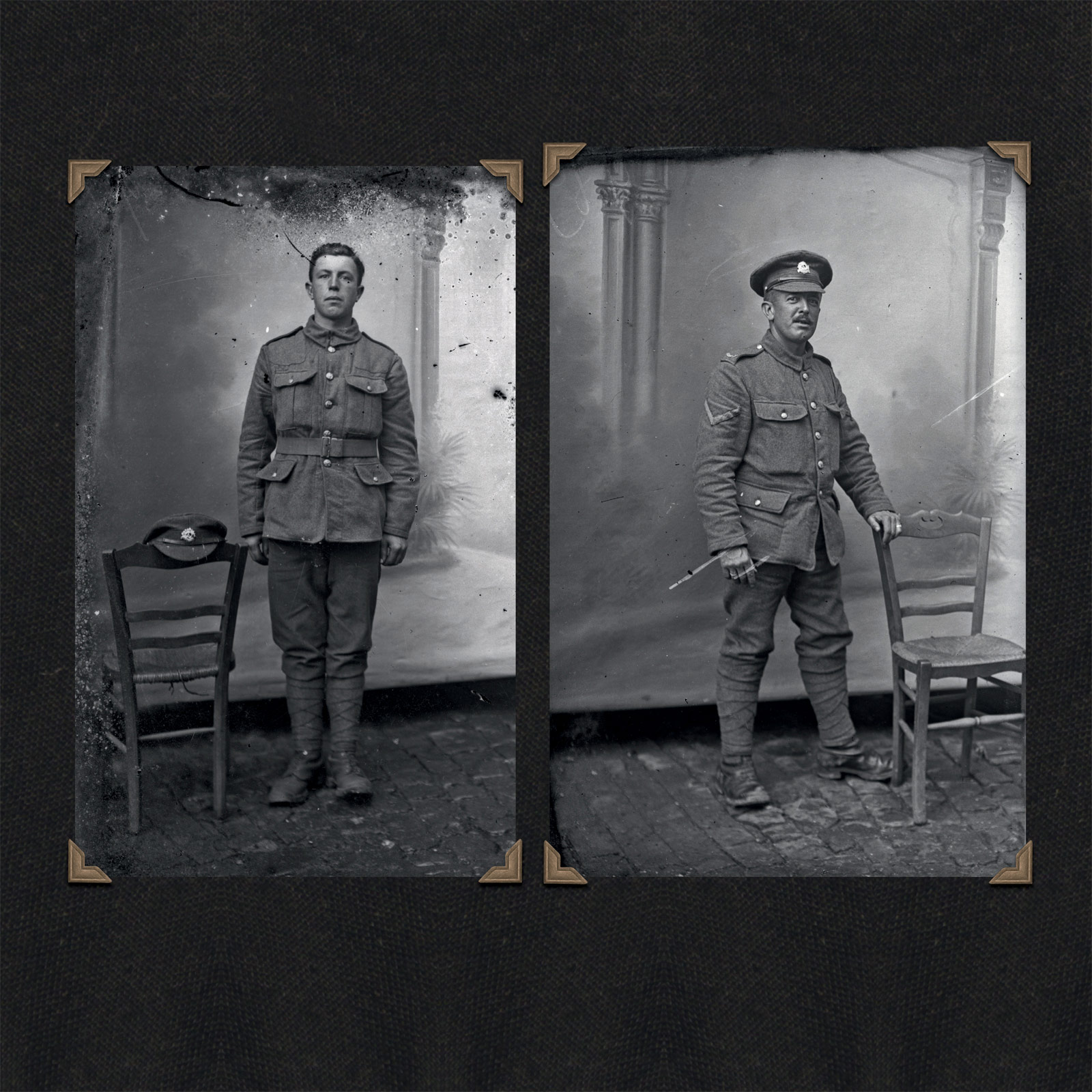

PLATE 38 An unidentified soldier. No clues as to his regiment can be seen in the photograph.

The Backdrop

One of the key clues that helped us track the Thuillier collection was the distinctive backdrop that appears behind soldiers and civilians in many of the pictures. Well before the discovery of the Thuillier portraits, historians at the Australian War Memorial had noticed the length of painted canvas in a handful of images of different soldiers held in its collection, and they were excited by what it implied. If a photographer had taken the trouble to paint a backdrop for posed photographs somewhere behind the front line, maybe there were more to be found than the dozen or so that had made their way into official collections.

PLATE 39 An excellent Thuillier image showing how the backdrop was used – the soldier is probably from the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons.

Never did we think it possible that the backdrop used by Louis and Antoinette Thuillier could have survived nearly a century in a dusty attic. But, as we fumbled around in the eaves of the family attic in Vignacourt back in early 2011, we found, wedged between two roof beams, a tight roll of canvas mounted on a wooden pole. Eager to see what was inside, but anxious not to damage it, we lugged the dusty canvas roll down the three flights of stairs to the courtyard … and gently unrolled it.

PLATE 40 Unfurling the backdrop. (Courtesy Brendan Harvey)

It is a little damaged from its near-century in a draughty attic, but the distinctive double archway seen in many of the photographs is still clearly visible.

PLATE 43 Close-up of the backdrop. (Courtesy Brendan Harvey)

There are hundreds of photographs in the Thuillier collection which clearly predate the painted canvas backdrop – many of them are probably pre-war images of French civilians and then, when war broke out in 1914, they feature the French soldiers who used the town as a staging post before they headed up to the front lines. As business picked up, Louis and Antoinette must have decided that a painted canvas backdrop offered a more professional look for their clients and so the first images using the backdrop began to appear.

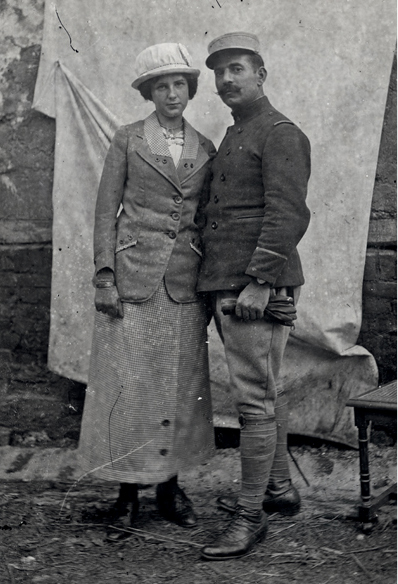

PLATE 41 An early Thuillier photograph of a French second lieutenant, of the 4th Colonial Infantry Regiment, and his wife, without the distinctive backdrop. Likely to have been taken sometime in July 1915 when the French 1st Colonial Corps was billeted in Vignacourt.

PLATE 42 A French soldier and his family in front of the distinctive Thuillier canvas backdrop.

PLATE 44 A soldier poses in front of the Thuillier backdrop, using a chair as a prop. The distinctive high table used in many other photographs can be seen just to the left. This soldier has two good-conduct chevrons on his lower left sleeve, indicating that he has six years with a clean record of service on his army record.

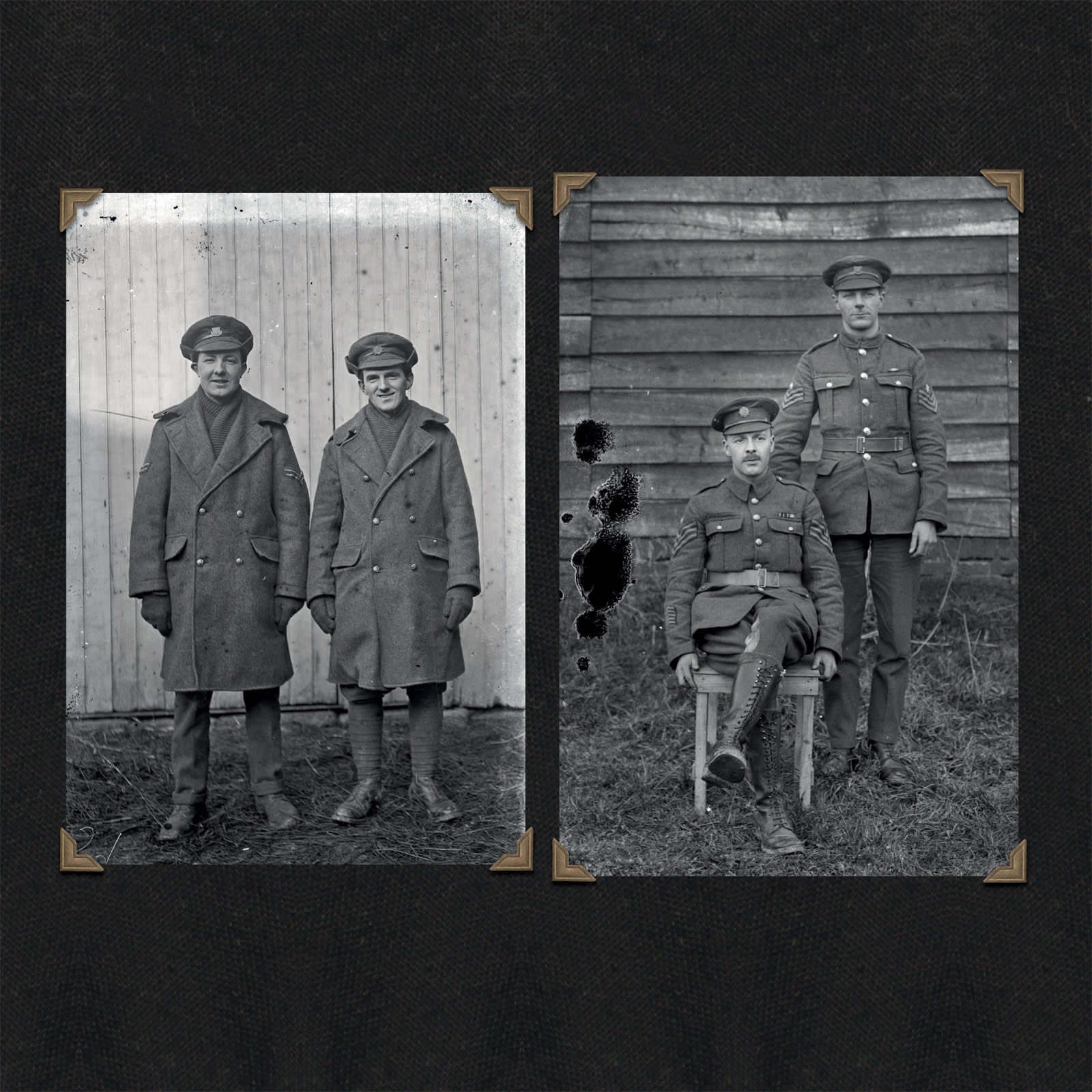

PLATE 45 A soldier from the Royal Engineers. His armbands show he is a qualified signaller. Possibly taken when the engineers were in and around Vignacourt in early 1916 preparing transport links and hospitals for the Somme offensive.

PLATE 46 Soldiers of the Royal Artillery Regiment, two with good-conduct chevrons. Clearly Thuillier moved his backdrop according to the state of the weather. The soldier in Plate 44 stands on a smooth cement floor in a covered area. This image is taken outside on cobblestones. It seems likely the smoother-floored area was used by Thuillier later in the war – hence this image predates Plate 44. However, the tunic worn by the soldier seated left is an ‘economy tunic’ without pleated pockets and without the rifle patches over the shoulders – which was issued only in 1916.

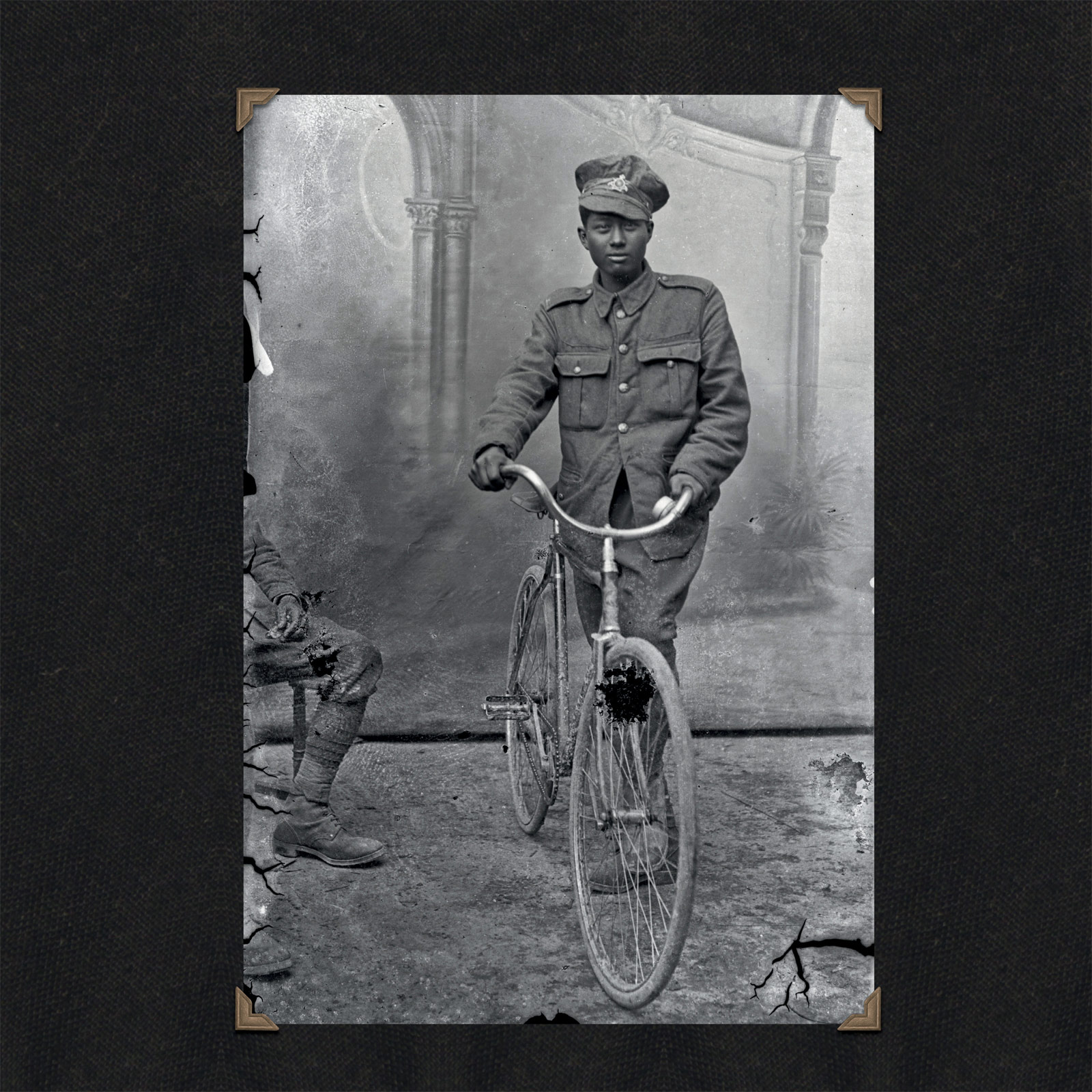

THE VIGNACOURT BREAD BOY

The discovery of the Thuillier glass plate images has been as moving for many of the villagers of Vignacourt as it has been for the numerous families who have searched for their relatives among them. In November 2011 hundreds of townsfolk came to Vignacourt’s town hall to view the two Australian Seven Network television documentaries that had been produced at that time on the ‘Lost Diggers’, subtitled in French for the occasion. For the village it was a chance to learn more about a chapter in the region’s history that only a few of the elderly villagers still recalled. Around the walls of the town hall, many poster-sized prints of some of the iconic Thuillier photographs also drew an excited response. For even after nearly a hundred years, some Vignacourt families were excitedly identifying their loved ones among several of the pictures taken of civilians during the conflict.

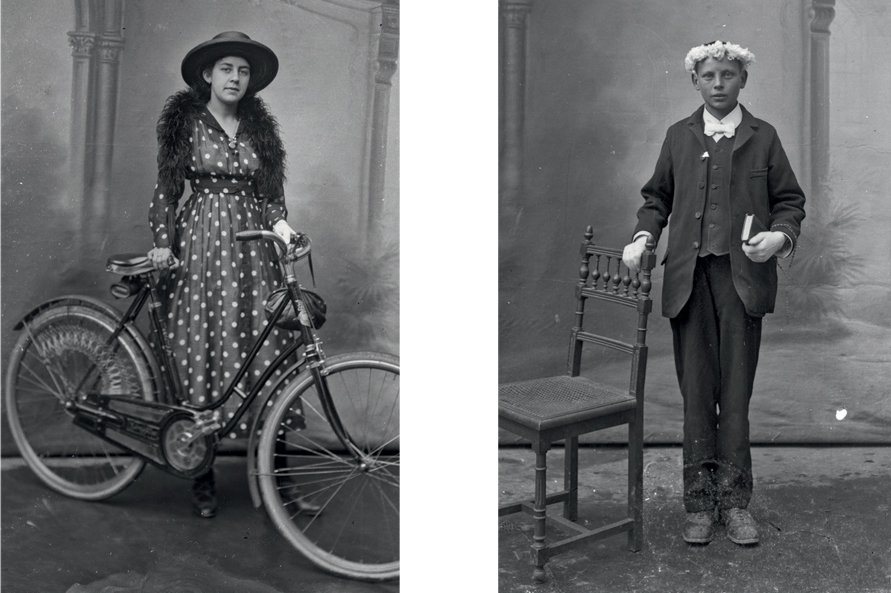

The young lad in Plate 47 was recognized by his family as Abel Théot. At the time this photograph was taken by the Thuilliers, the boy’s life was one of hardship and sadness brought about by the war. Abel was one of five brothers, two of whom died fighting in the French army against the Germans. His father was away at war, too, and Abel sold bread and pastries to Allied troops to bring in extra money to help his mother and family survive. Tragically, after this photograph was taken, Abel learned that his father had also died in the fighting; another of his brothers returned with serious wounds.

PLATE 47 Abel Théot, the Vignacourt bread boy.

How the Thuilliers Took Their Photographs

It was another Frenchman, Louis Daguerre, who had invented one of the most important precursors of modern photography, the daguerreotype, in the 1830s – the Polaroid of its day. The daguerreotype produced a single image, which was not reproducible. In the 1850s, more than sixty years before the outbreak of the First World War, William Henry Talbot devised the negative process in which a glass plate negative allowed any number of prints to be made. But the glass plate technology came under threat from the nascent celluloid film cameras produced by Kodak in the late 1880s. By the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, black and white box brownie cameras were relatively common and it is intriguing to speculate just why Louis and Antoinette Thuillier did not opt for the much cheaper film cameras that were by then available. Perhaps the pair were purist professional photographers – and there were many right up even to the 1970s – who continued to favour glass plates because of concerns that the early celluloid films could not provide the sharp images so beautifully rendered by the older glass plate negative technology. Glass plates are still used for photography today in some scientific applications. The problem of sharpness in the early celluloid film cameras was caused by the poor lenses; and nor could early film camera technology provide a sufficiently reliable flat focal plane compared with that provided by a glass plate camera. This was because the celluloid film, although stretched across the back of the camera, still curved slightly and this made for less crisp images. All the better for amateur historians a century later, because the glass plate negatives used by the Thuilliers allow for an extremely high-quality print in comparison with the old celluloid film negatives, most of which have degraded to the point where they are unusable.

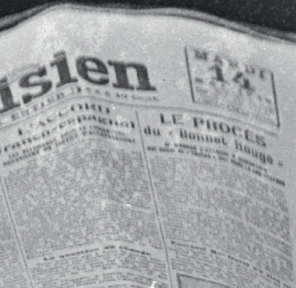

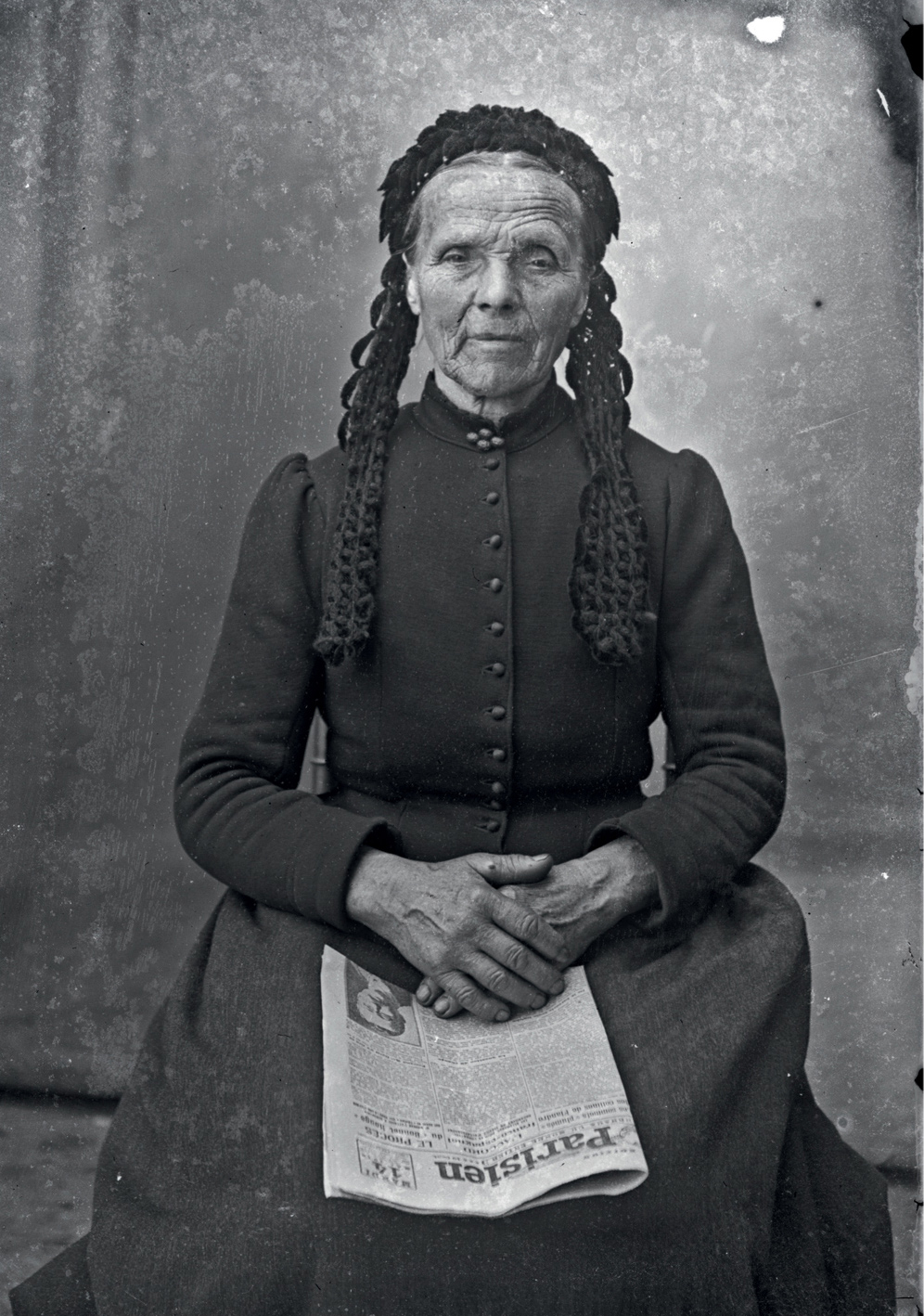

PLATES 48–49 An example of the high resolution possible from modern scanning of the Thuillier plates – the date on the Parisien newspaper in this elderly Frenchwoman’s lap can be read in the close-up image. Translated, it says either ‘Tuesday, 4 May 1915’ or ‘Tuesday, 14 May 1918’.

Another good reason for photographers like Louis and Antoinette Thuillier to use glass plates could have been one of economy: they had the option to reuse the glass plates once they had developed them and sold the positive prints. Reusing a plate would have simply entailed cleaning off the silver image on it. But the Thuilliers clearly kept most, if not all, of the plates they shot. What is exciting about this is what it suggests about their motives for taking the photographs in the first place. For if Louis and Antoinette Thuillier had only cared about their portrait subjects as commercial transactions, they could easily have recycled the plates once they had sold each soldier his picture. For whatever reason, Louis and Antoinette preserved the exposed plates; and, by the look of it, they kept nearly all of them, filling their attic with thousands. It is possible they realized the wartime portraits they were taking would one day be of enormous historical significance and worth. Even today in the Thuillier family attic there are sections of what appear to be old glass window plates from which Louis and Antoinette had cut glass in the size and shape of negatives. Glass was clearly so precious a commodity during the war that they were removing it from windows to fulfil demand.

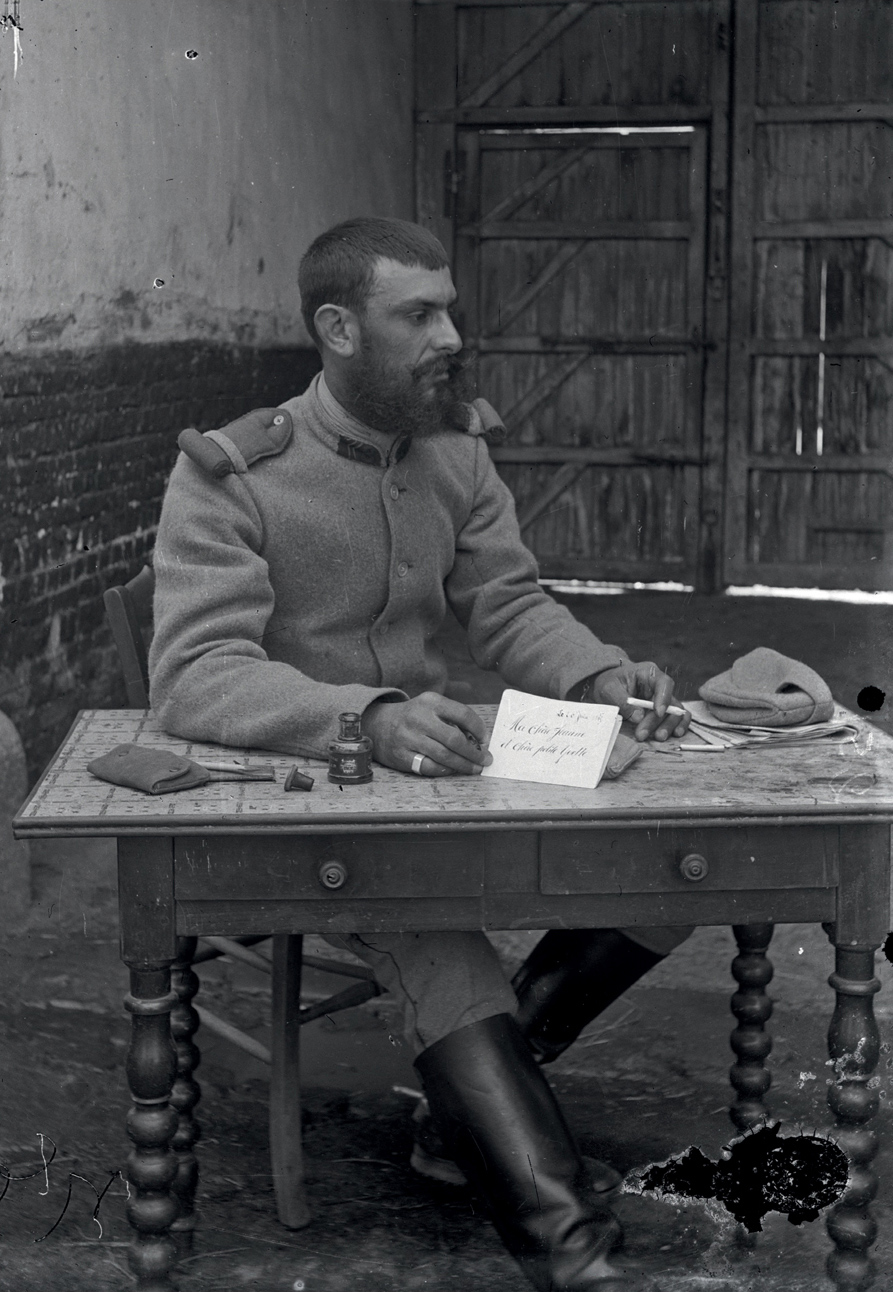

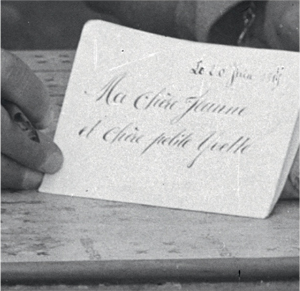

PLATE 50 A French cavalryman of the 1st Cavalry Division writes a letter to his family on 20 June 1915.

PLATE 51The glass plate’s high resolution allows us to read what he has written: ‘My dear Jeanne and my dear little Yvette’. The division was based in Vignacourt from May to June 1915.

There is no information on the Thuilliers’ camera or cameras. Their equipment was stolen by the Nazis in 1940 when Vignacourt was evacuated during the German Somme offensive (many Vignacourt homes were looted at that time). But because there are different-sized glass plates in the surviving collection, the couple probably used a camera that allowed interchangeable sizes of backing so that different sizes of glass plates could be fitted. It was also possible to have one sheet of glass – a ‘single dark’ – or a ‘double dark’, which allowed two glass sheet exposures to be taken using a sliding magazine.

PLATE 52 This Army Services Corps soldier is reading an album called ‘Album P.A.L. 1914–1915’, which means this image must date from 1916 or later.

The basic concept of glass plate photographic cameras is no different from the more modern photographic film and printing papers. All contain an emulsion of silver-halide crystals suspended in gelatin. The plate is exposed to light in the camera as the photograph is taken, then, to ‘develop’ the image, the plate is immersed in a chemical bath to render the exposed silver halides into the metallic silver that makes the image visible. To stop the silver from reacting any further to light, the image on the plate is ‘fixed’ by immersing it in a bath of ‘hypo’ (sodium hyposulphate). Any leftover chemical then has to be washed out of the image to stop the picture from leaching.

To print copies of the plate speedily for their soldier customers, Louis and Antoinette may have used a process that did not require a darkroom to develop the printing paper in a wet bath. Known as ‘POP’ – short for printing-out paper – it allows a photographer to produce a visible image upon exposure to light without using chemicals. The plate was exposed against a sheet of light-sensitive paper, producing an image the same size as the glass sheet – a technique also known as a ‘direct contact print’. One limitation of this POP technology was that the paper print tended to fade, which perhaps explains why so few of the Thuillier prints survived the past century. Those faded pieces of yellowed cardboard sitting in the family archives of old servicemen may well be the speedy postcard snaps produced in Vignacourt by the Thuilliers.

What is even more extraordinary about the images in this book is that they are reproduced at a resolution far higher than their subjects ever saw when they purchased prints around a hundred years ago from the photographers. Methodical cleaning and high-resolution scanning have reproduced digital copies of the plates, which were then optimized using computer software such as Photoshop. The rare Thuillier images that did survive the past century are those that were rephotographed after the war using more stable photographic techniques.

PLATE 53 A sharp image of an Army Services Corps sergeant on a Douglas motorcycle. During the war the Bristol-based Douglas Company supplied more than 70,000 motorcycles. They were used by dispatch riders, signallers and engineers. The ASC sergeant pictured was probably carrying medical supplies in the attached leather cases.

The photographic plate digital scanner used to reproduce the images in this book has a resolution one hundred times better than the print paper used in 1914–18. Even though Plate 55 below is slightly damaged, it is still possible to read this soldier’s map.

PLATES 54-55 An Australian dispatch rider’s map case. A close-up shows he has a map detailing the area north of Amiens.

Louis and Antoinette Thuillier and the Town of Vignacourt

We have little information about Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, the pair behind the camera. What is known is that Louis was born on 29 July 1886 into a modest Picardy farming family, and that as well as working as a farmer he embraced the new technologies of the early twentieth century with zeal. He married a beautiful local girl, Antoinette Thuillier (same family name, but no relation), when he was twenty-six and started up what soon became a thriving farm machinery business.

PLATE 64 The Thuillier family’s farmyard, probably before or very early in the war, one of the earliest photographs in the collection. This is where Thuillier hung his backdrop and photographed thousands of soldiers throughout the war. The backyard still exists today – and still looks much the same.

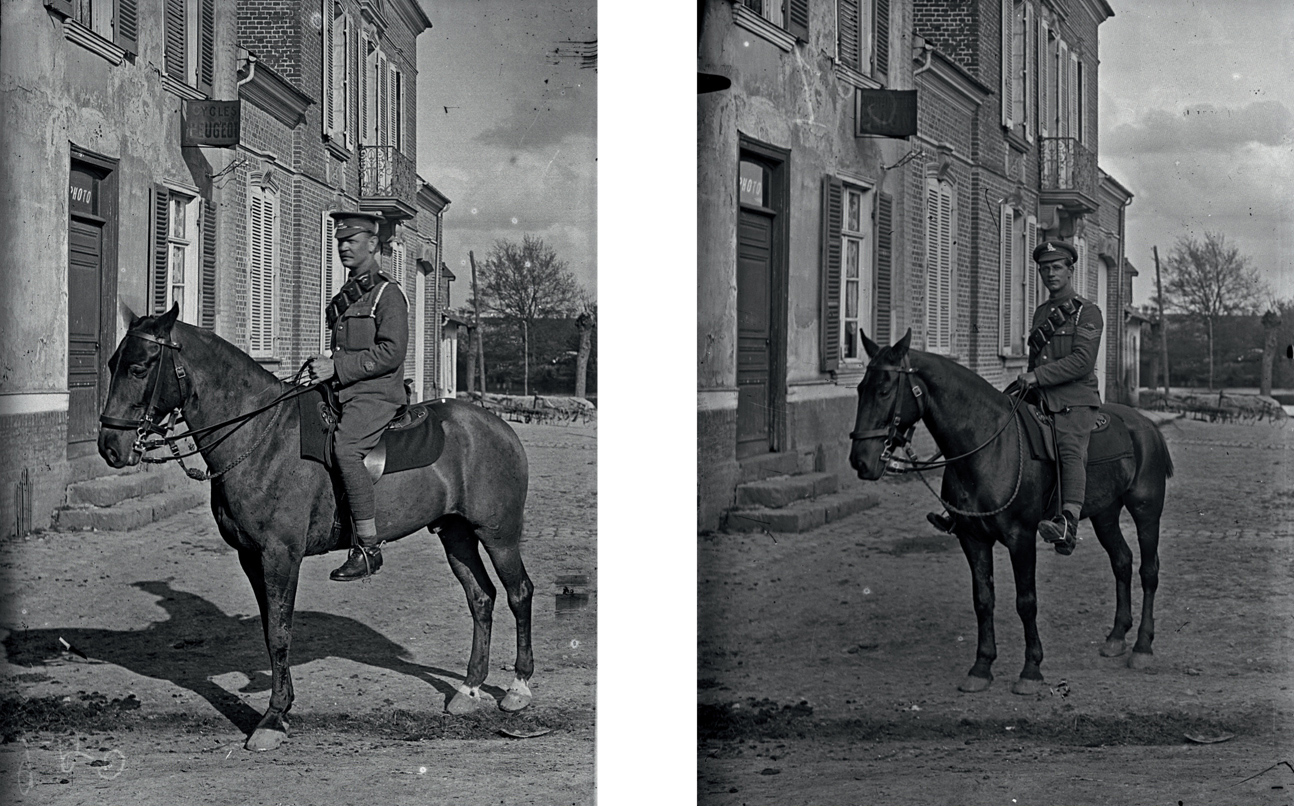

Vignacourt locals knew Louis as ‘Peugeot’ Thuillier because he also set up a Peugeot bicycle repair shop in 1907 in addition to his own agricultural machinery hire firm. To this day the backyard of his old farmhouse complex is cluttered with rusting machinery, old wheels and the well-tooled workshop of an avid machinist who was clearly very good with his hands. At some stage Thuillier taught himself glass plate photography and he began photographing local villagers.

PLATE 56 A British supply wagon outside the Thuillier farmhouse during the First World War. Note the ‘photo’ sign in the window above the front door at the left of the image.

PLATES 57 – 58 A local Vignacourt woman poses in a beautiful polka-dot dress and a boy poses with a garland and communion Bible.

PLATES 59 – 60 Two young lads – one smoking! – pose for the Thuilliers and (right) a sobering illustration of how the war influenced young local children: this boy has a toy machine gun and uniform.

The Peugeot sign he placed on the front of his house as an advertisement to passing cyclists also appears in his images (see Plates 65–66, below).

PLATES 65 – 66 Exteriors of the Thuillier home, with Peugeot sign. Both soldiers are members of the Royal Horse Artillery.

Louis enlisted soon after war broke out, but his war service is something of a mystery because his service file was one of many destroyed in a bombing raid in 1940. He was a dispatch rider, taking signals and documents between positions on the front lines, a job that almost certainly cemented Louis’s lifelong passion for motorcycles (which feature in many of the Thuillier pictures, and explain the piles of motorcycle magazines in the attic). Louis was wounded and after recuperating in a hospital he was demobilized and home in Vignacourt by 1915. The war also took its toll on Antoinette’s family. She had two brothers, Louis (another Louis, to confuse matters) and Gustave. Brother Louis was captured by the Germans and became a prisoner of war, but he survived to return home after the Armistice. Gustave, who served with the 72nd Infantry Regiment, was killed in a German gas attack on 20 March 1918, aged twenty-four.

PLATE 61 Louis Thuillier (from the Thuillier collection), probably taken by his wife, Antoinette.

PLATE 62 Antoinette Thuillier. (Courtesy Bacquet family)

PLATE 63 Louis Thuillier in French army uniform, c. 1915, with an unidentified child (perhaps Robert Thuillier, born 1912). (Courtesy Bacquet family)

By the time Louis Thuillier returned home from his wartime service as a dispatch rider, the town was full of French troops waiting to head up to the front lines, and he began photographing them for extra money. He taught Antoinette how to take photographs as well because he also had to run the family farm. Vignacourt was becoming a key rest and hospital village behind the front lines, and the couple realized they could make good money selling portraits to the passing French and Allied soldiers.

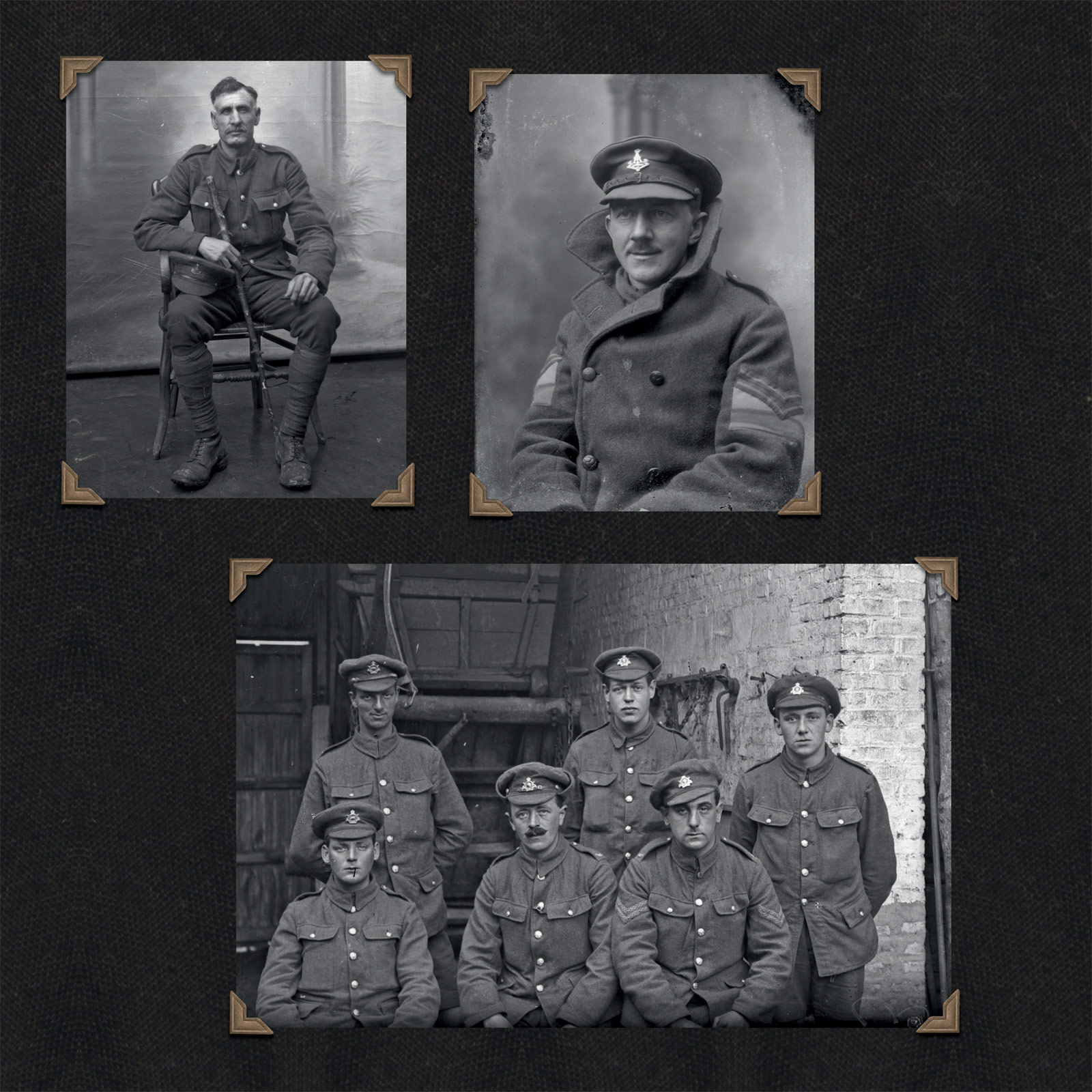

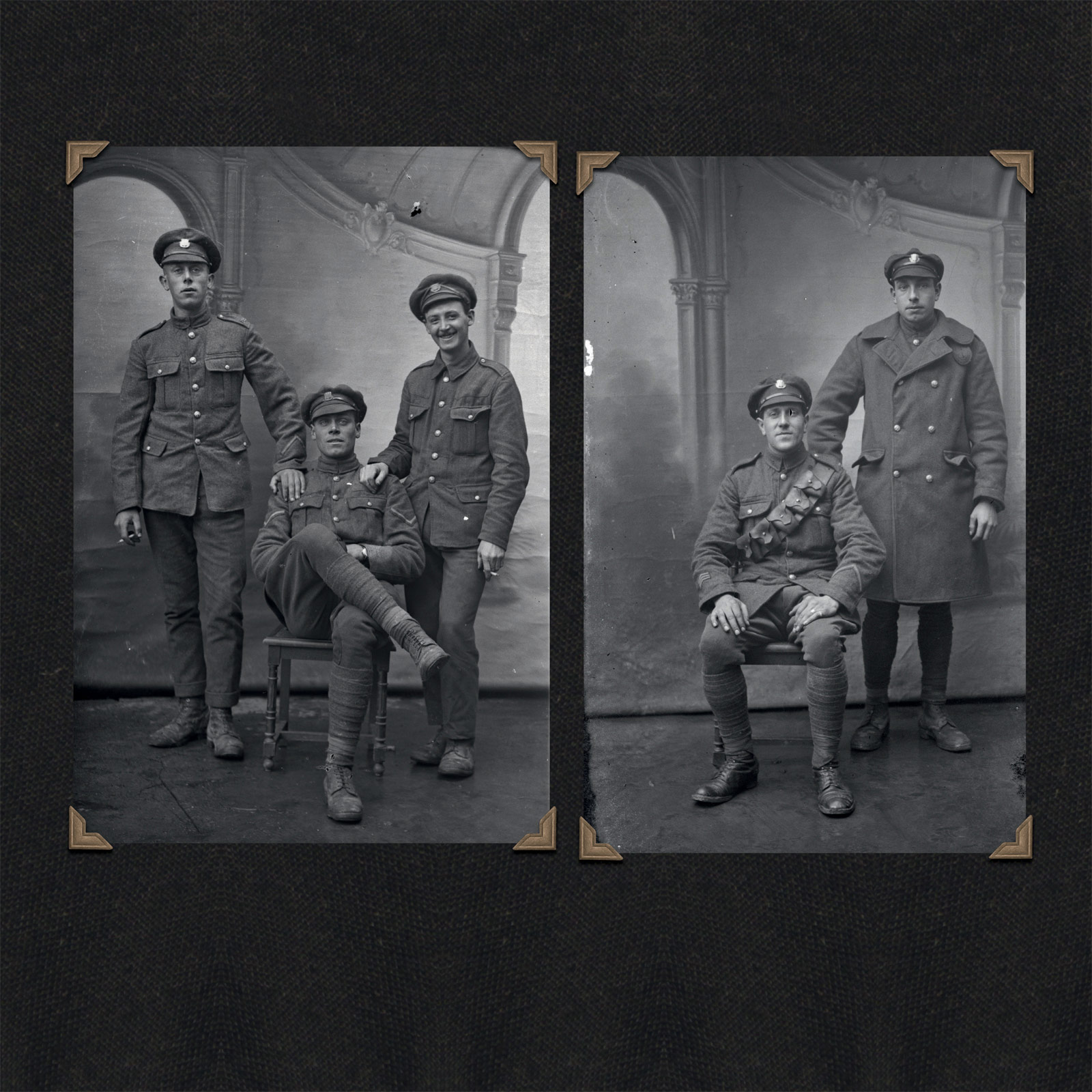

IDENTIFYING BRITISH REGIMENTS

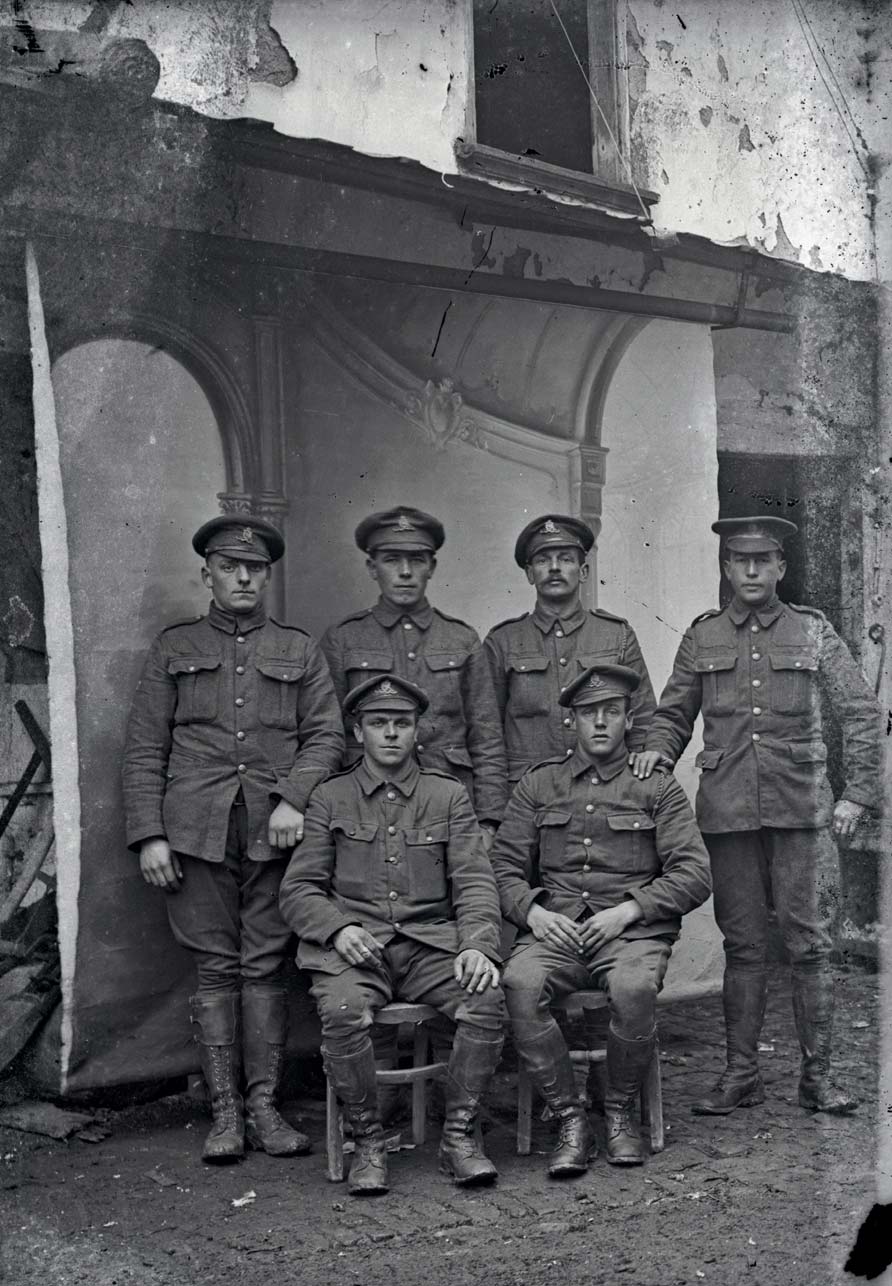

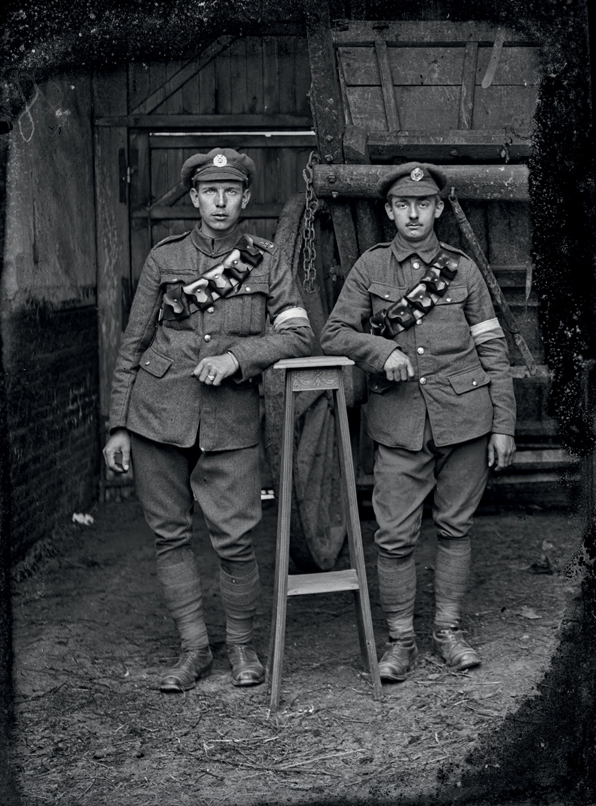

During the First World War every British regiment and corps had its own cap badge and it is these badges, worn on the uniform or caps of soldiers, which have allowed us to identify the individual British Army regiments in the Thuillier collection. For example, close examination of Plates 68 and 69 reveals that all the soldiers featured have the distinctive Royal Welsh Fusiliers cap badge.

PLATE 67 A version of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers cap badge.

PLATES 68 – 69 A corporal and a lance corporal of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (left), and a major (right). The Royal Welsh Fusiliers were probably one of the first British regiments to be based around Vignacourt in late September 1915.

A diary kept by Abbé Leclerq, the Vignacourt village priest at the time,1 reveals that the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, one of the British Army’s oldest regiments, was one of the first regiments to be based in and around Vignacourt during the First World War. On 27 September 1915 he noted the arrival of the first British troops in the area – the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, one of the South Wales Borderers regiments and a platoon of Royal Engineers, who settled in and around Vignacourt in billets and nearby camps. Vignacourt was to become home to the staff of the British 13th Army Corps between January and July of 1916. The Royal Engineers are very nearly the most photographed unit among those in the Thuillier collection, probably because, as Abbé Leclerq recorded, they came to Vignacourt so early in the war, and units of engineers were there for the duration.

PLATE 70 Two soldiers of the Royal Engineers Corps pose in the Thuilliers’ farmyard. Both wear armbands indicating they were in the Royal Engineers Signal Service. The soldier on the left wears the distinctive ‘T’ of the territorial force on his left shoulder.