Полная версия:

The Lost Tommies

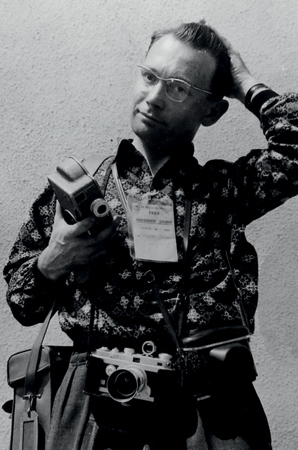

The real hero of this story is Laurent Mirouze, a Loire Valley antiques and furniture dealer as well as a published historian and experienced journalist. Late in the 1980s, one of Laurent’s friends, who knew of his passion for military history, mentioned that he had seen some beautiful photographs of First World War soldiers on the walls of a council building in the small Picardy town of Vignacourt, just north of the city of Amiens. Sensing a good story, Laurent decided to drive the few hours from his home to Vignacourt to take a look. There, hanging on the walls of the tiny council offices, were the most extraordinary pictures featuring Allied soldiers, mainly British and Australians. Only about twenty pictures were exhibited, but Laurent eventually tracked down the photographer who had printed them from the original plates, a Vignacourt resident, Robert Crognier.

PLATE 15 Robert Crognier. (Courtesy Madame Crognier)

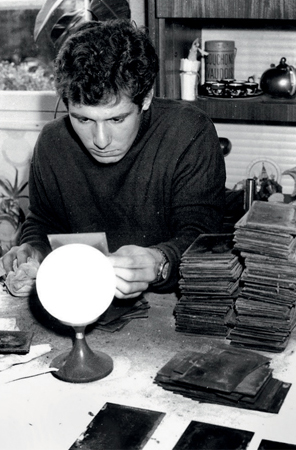

PLATE 16 Laurent Mirouze inspecting some of the Thuillier plates in 1989 before they disappeared. (Courtesy Laurent Mirouze)

When Laurent visited Monsieur Crognier at his home in 1989, he was astonished to discover that the photographs he had seen displayed at the local council offices were just the tip of an iceberg. There were thousands of pictures on photographic glass plates, he was told. He learned of Louis and Antoinette Thuillier and Monsieur Crognier told him the plates were still in the possession of the family. (Monsieur Crognier was a nephew of Louis and Antoinette, and he had reproduced the images from the plates with the permission of Roger Thuillier, one of their sons.) Monsieur Crognier explained to Laurent that the collection was housed at the time in a family home in Vignacourt and, while he let Laurent take photographic prints of several hundred of the plates, he never disclosed the precise location of the full collection. As it turned out, this was an entirely separate collection from the photographs later published by the Independent.

Laurent realized very quickly that the plates were hugely important not only to British but all other First World War Allied countries’ military history. They were also a cracking good story for this aspiring military historian. He had himself photographed reviewing the plates, thinking – not without good reason – that he would have media and military historians beating a path to his door to view the collection. With the permission of Robert Crognier, Laurent wrote an article in France and England, revealing the discovery and publishing some of the images.

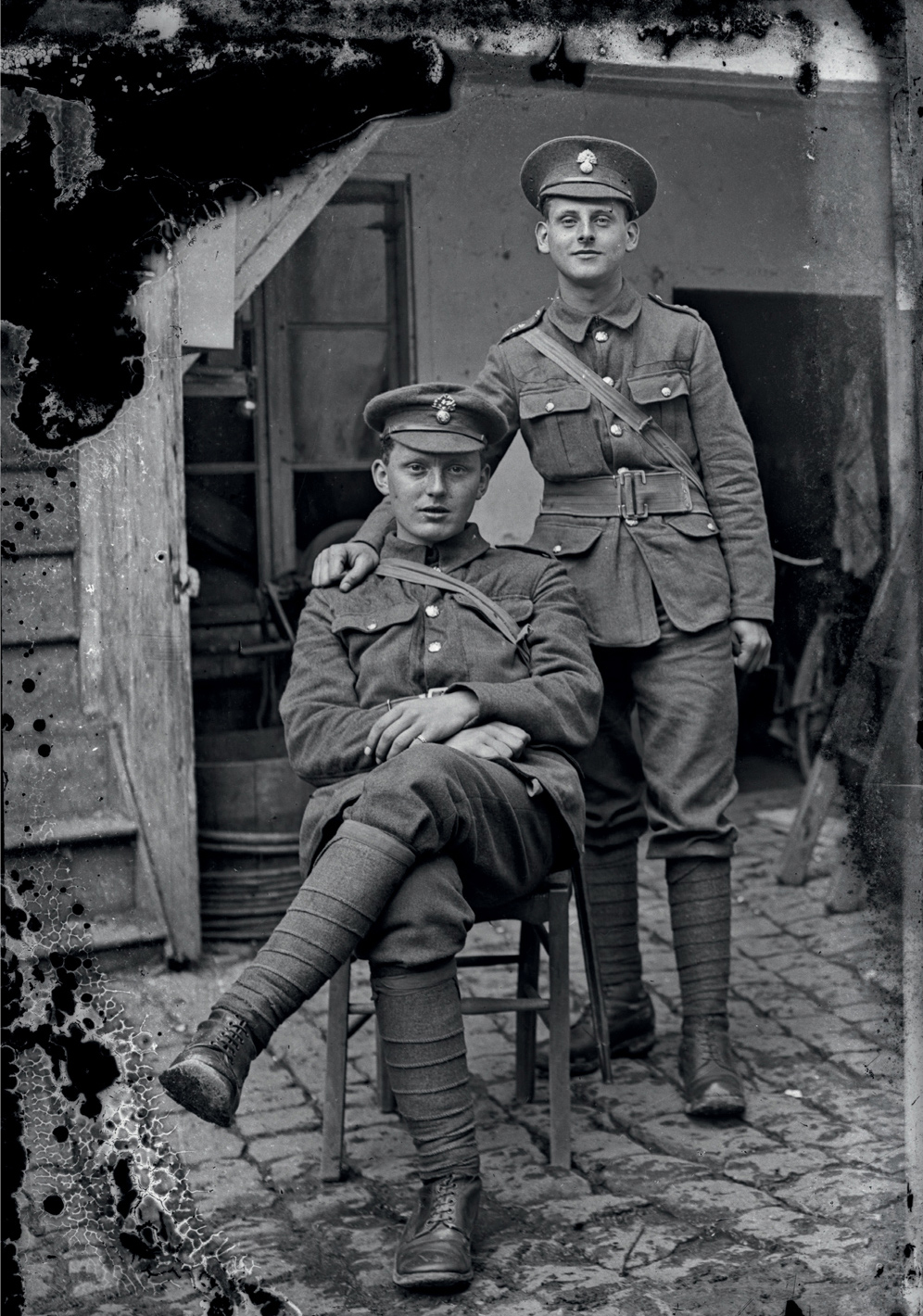

PLATE 17 Two Royal Fusiliers. The soldier standing wears the stiff service cap and the soldier seated the softer cloth cap introduced after the war began.

In the spring of 1990 Laurent also rang the Australian Embassy in Paris, formally writing to them and sending them copies of some of the pictures so they could see for themselves. ‘I said there’s hundreds of them – could this be of any interest to you?’ Laurent recalls. ‘But I could feel very clearly that they were not very interested in the story. A shame!’ Laurent laconically comments today, ‘Maybe these people are not interested in the First World War.’ Laurent never heard back from anyone at the Australian Embassy, nor did he get much interest from British researchers. Despite this, he made one last effort to alert military historians to his discovery by publishing a story about the Thuillier collection in a British military magazine, Military Illustrated, in November 1991. Absurdly, nobody ever contacted Laurent Mirouze. So he got on with his life, thinking no one was interested.

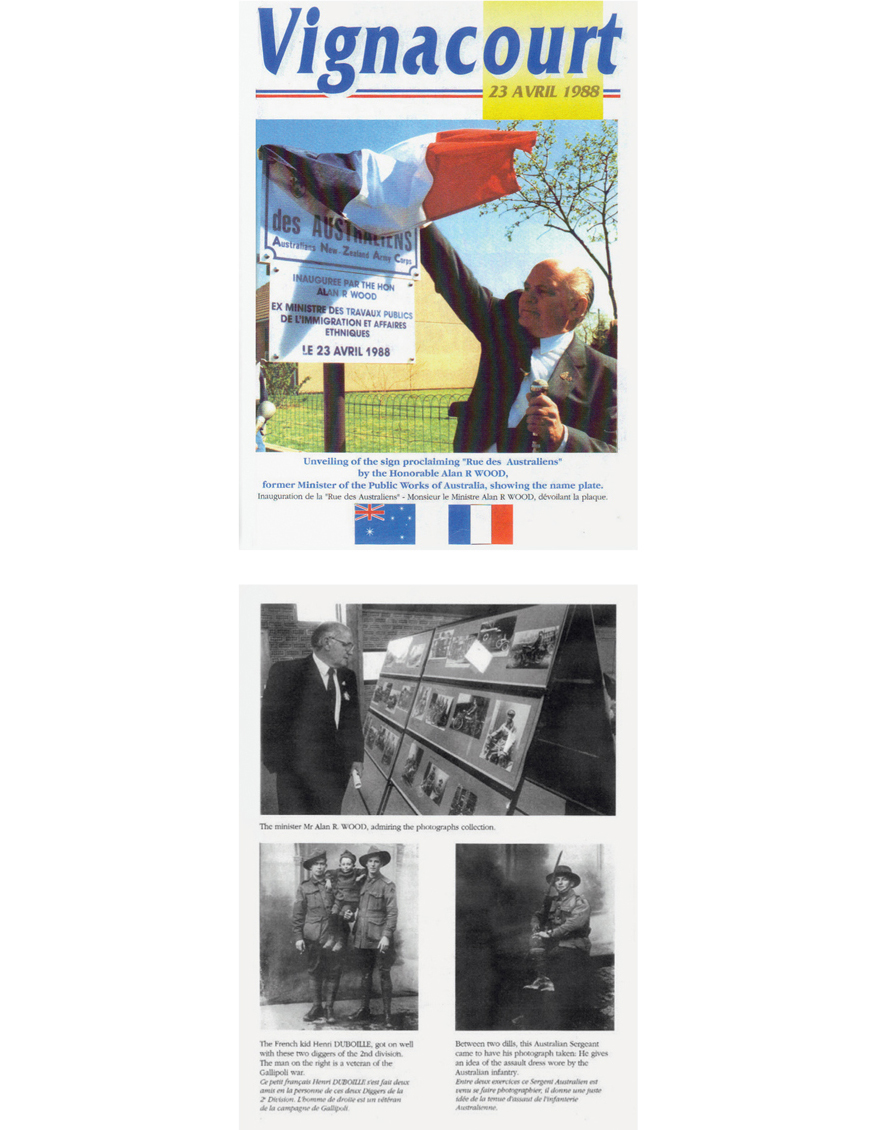

But there was someone else also trying to track down the Thuillier plates. Peter Burness, a historian from the War Memorial in Australia, is a tenacious military history investigator and a passionate First World War buff. In about 1990 a small commemorative pamphlet published in Vignacourt had landed on his desk. It featured a small sample of the prints of Allied soldiers which had been retrieved from the Thuillier plates by Robert Crognier. The pamphlet even helpfully told readers that these pictures were a fraction of the 3,000 or more images taken by Thuillier and his wife. ‘The photographs of this booklet are only samples of the collection,’ the pamphlet reads.

PLATES 18–19 The cover and images from the Vignacourt brochure featuring some of the Thuillier pictures.

The pamphlet had been produced for a commemorative ceremony on 22 April 1988 in Vignacourt. The guests included dignitaries and officials from the Australian Embassy in France. They were there for the dedication of one of the town’s streets to Australia, to be called ‘Rue des Australiens’, a tribute organized by Robert Crognier, the mayor Michel Hubau, and René Gamard, a Vignacourt historian. The Frenchmen were honouring a promise made back in 1918 by the town’s then mayor, Monsieur Thuillier-Buridard, to keep an ‘eternal bond’ with Australia and other Allied nations that had fought for France’s freedom.

For the ceremony, a small number of the Thuillier images were displayed by the proud locals. Like so many French people, the villagers of Vignacourt still honour the Allied soldiers who died for their freedom. Unfortunately the visiting officials seemed to have had no idea of the significance of the photographs and were still ignorant of their importance two years later when Laurent approached the Australian Embassy in Paris. However, gazing at the pamphlet on his desk, Peter Burness recognized the plates’ historical importance and set about trying to track down the source. Sadly, by the mid-1990s, Robert Crognier was ill and in 1997 he passed away. Repeated efforts to contact the remaining Thuillier relatives through the town council offices failed. Despite years of searching, it seemed the more Peter hunted for the elusive Thuillier collection, the more he sensed a deliberate evasiveness by some around Vignacourt. So the whereabouts of these photographic plates remained unknown.

In the course of our investigations, we approached a British historian, Paul Reed, who is well known for his books on the First World War and who also lives part of the year in a house in the Somme countryside. Paul was unable to shed any further light on the provenance of the Warloy-Baillon collection, but he did tell us about Laurent Mirouze, whom he had heard might know something about another collection of photographs.

From the moment we first spoke to Laurent, the Frenchman was overjoyed that somebody had finally contacted him. ‘I’ve been waiting twenty years for this,’ he said to us in our first phone call late in 2010. He told us that his photographer friend Robert Crognier had died in 1997, but Laurent agreed to help in the search for the full collection of plates. It was not an easy task. Each time we rang Vignacourt locals, our efforts to find Thuillier relatives were met with a polite rebuff. The family members with knowledge of the collection seemed to have disappeared. It was only later, when we actually knocked on their door, that we learned of an internal family rift; some members of the Thuillier family did not want the collection to be found. We learned that the Thuillier images had ‘disappeared’, probably because some family members, now dead, resented the way that all First World War memorabilia was being acquired by the French government in order to build up the collections of its war museums – including the large regional museum in nearby Péronne. It would seem the Thuillier plates went underground after the 1988 ceremony because some locals did not want the French government to plunder a piece of Vignacourt heritage without giving adequate compensation in return.

And so it happened that on a cold February morning in early 2011 in Vignacourt, we began where Laurent’s quest had ended twenty years earlier, at Vignacourt’s council building. There in the council chambers we saw the handful of tantalizing pictures hanging on the walls. The Australian War Memorial historian Peter Burness was with us and he was amazed by the quality and clarity of the images on the council chambers’ walls. The big question now was, where was the rest of the collection?

PLATES 20–21 Laurent Mirouze back where the trail started in 1989, and showing Peter Burness what he found on the walls of Vignacourt’s council chambers.

The breakthrough came after a day or so of knocking on doors led us to Madame Henriette Crognier, Robert’s widow, who still lived in the town. We were ushered into her cluttered living room and, as her cat purred under the table, Madame Crognier’s bright eyes scanned ours as we spoke of our search for the pictures. When we explained in detail the enormous historical significance of the pictures, and expressed our hopes that the Australian images at least would be displayed at the War Memorial, Madame finally let a gentle smile lift the corners of her mouth and with a twinkle in her eye she left the room.

Laurent was acting as our translator, and I anxiously asked him if we had said something to upset her. ‘No,’ he replied. ‘She says she has something for you.’ Madame Crognier had decided to trust us. Within a few minutes she returned with a couple of Second World War ammunition boxes under each arm, and a big smile on her face. She slid the metal cases over the table and, with her hand on one of them, said with a Gallic flourish, ‘Pour les Australiens,’ and flicked the lid open.

PLATE 22 Madame Crognier shows Peter Burness and Laurent Mirouze her secret stash of Thuillier plates. (Photo: Ross Coulthart)

After all these years she still had some of the Thuillier glass plates her husband had retrieved from the family’s hiding place. Better still, she believed the remaining thousands of plates were indeed still in Vignacourt in a farmhouse owned by Louis Thuillier’s grandson and granddaughter. We sat there stunned. ‘Thousands of plates?’ I asked. ‘Thousands of plates,’ Laurent confirmed the translation. I stumbled on for confirmation: ‘… that have never been seen before?’ ‘Oui,’ Madame replied, now delighted with our reaction.

Through Madame Crognier we learned of the surviving descendants of Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, among them their granddaughter, Madame Eliane Bacquet, and their grandson, Christian Thuillier. Neither of them lived in Vignacourt any more but they did still jointly own the empty farmhouse where Louis and Antoinette had offered their photographic services to passing soldiers. Finally, after days of intense negotiations, they agreed to take us to the farmhouse. As it happened, our timing was propitious because the family was thinking of selling the old farmhouse and, in a few months, we were told its contents might well have been thrown on to a rubbish heap.

PLATE 23 A wartime photograph of the front of the Thuillier home at the time when many of the photographs were taken. (From the Thuillier collection)

PLATE 24 Exterior of the Thuillier farmhouse, Vignacourt, February 2011. (Photo: Ross Coulthart)

At the old kitchen table in the run-down farmhouse, Madame Bacquet told a sad story from the Great War. Her mother, the daughter-in-law of Louis and Antoinette, had described how as a young woman during the war she had heard the screams of young wounded men passing through the village in horse-drawn ambulances. ‘They were calling for their mothers,’ she said. ‘It was very sad.’

PLATE 25 Soldiers of the Army Services Corps pose with their Dennis troop-carrier truck in the main street of Vignacourt during the war. The buildings behind them still stand today.

Madame Bacquet would have made a good probing military interrogator in another life, questioning us for several hours about our motives. As it became clear to her that our quest was an honourable one and that the proud memory of her ancestors would be fulsomely acknowledged, she brought out a collection of Thuillier family photographs. For the first time we laid eyes on Louis and Antoinette.

PLATE 26 Louis Thuillier. (Courtesy Bacquet family)

PLATE 27 Antoinette Thuillier. (Courtesy Bacquet family)

Christian Thuillier, Louis and Antoinette’s grandson, is a Normandy businessman.

He had been nominated by the family to show us around the farmhouse, and it was Christian who, with a wry smile, conceded that the answer to our quest for the photographs might lie in the attic above the building. We stepped out of the kitchen anteroom into a huge outside courtyard, our hearts missing a beat or two as he led us up several flights of stairs to the attic where the Thuillier photographic plates had been stored for nearly a century. It was as if Louis and Antoinette had just walked away from their massive project and dumped everything upstairs. In the gloom we could discern boxes of unused glass plates and empty bottles that had once no doubt contained the chemicals used to develop the prints. No sign of the original camera. But there, under the light of an attic window … three chests. As soon as we opened the first of them we knew our search was over.

PLATE 28 Antoinette Thuillier poses with her son in the same position where she and her husband photographed thousands of Allied soldiers during the First World War.

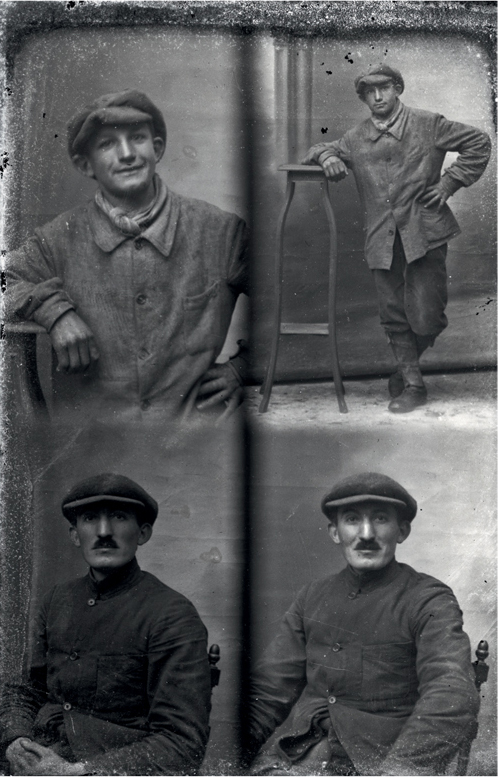

PLATE 29 The man in the bottom of this single four-exposure slide is a young Louis Thuillier, almost certainly taken by his wife, Antoinette – perhaps while she was learning to use the cameras?

PLATE 30 Ross Coulthart looks at the Thuillier plates with, from left, Laurent Mirouze, Christian Thuillier and Peter Burness. (Courtesy Brendan Harvey)

PLATE 31 An original Takiris silver bromide photographic paper box found in the attic. (Photo: Ross Coulthart)

Laurent recognized some boxes immediately. He had helped Robert Crognier sort through them nearly a quarter of a century earlier, but he had never learned of their hiding place. After Robert’s death, the plates had clearly been dumped and forgotten here in the attic. As we excitedly searched through box after box, we could hardly believe what we were seeing. The battered boxes were filled with thousands of glass negative photographic plates, and for hours we held them up to the attic window light, revealing often perfectly preserved ghostly negative images of thousands of British Tommies, Welshmen, Irishmen, Scots, Australian ‘diggers’, turbaned Sikhs, and French, Canadian and American soldiers. There were gasps of awe and excitement from all of us, especially Peter Burness, as he pulled out plate after plate. It seemed scarcely possible that this dusty attic, freezing in winter and no doubt stifling in the French summer, could have preserved the photographs so well. On this especially chilly winter’s day, it was sobering for all of us to think what it must have been like for the young soldiers in a French winter, nearly a hundred years earlier, as they endured the appalling conditions in the open trenches just twenty to thirty kilometres to the north-east.

Our quest for the elusive Thuillier collection was over, but our investigations into the stories behind the thousands of plates had only just begun.

PLATE 32 Labour Corps.

PLATE 33 Royal Army Medical Corps.

PLATE 34 Royal Engineers.

PLATE 35 Dorsetshire Regiment.

Identifying the Tommies

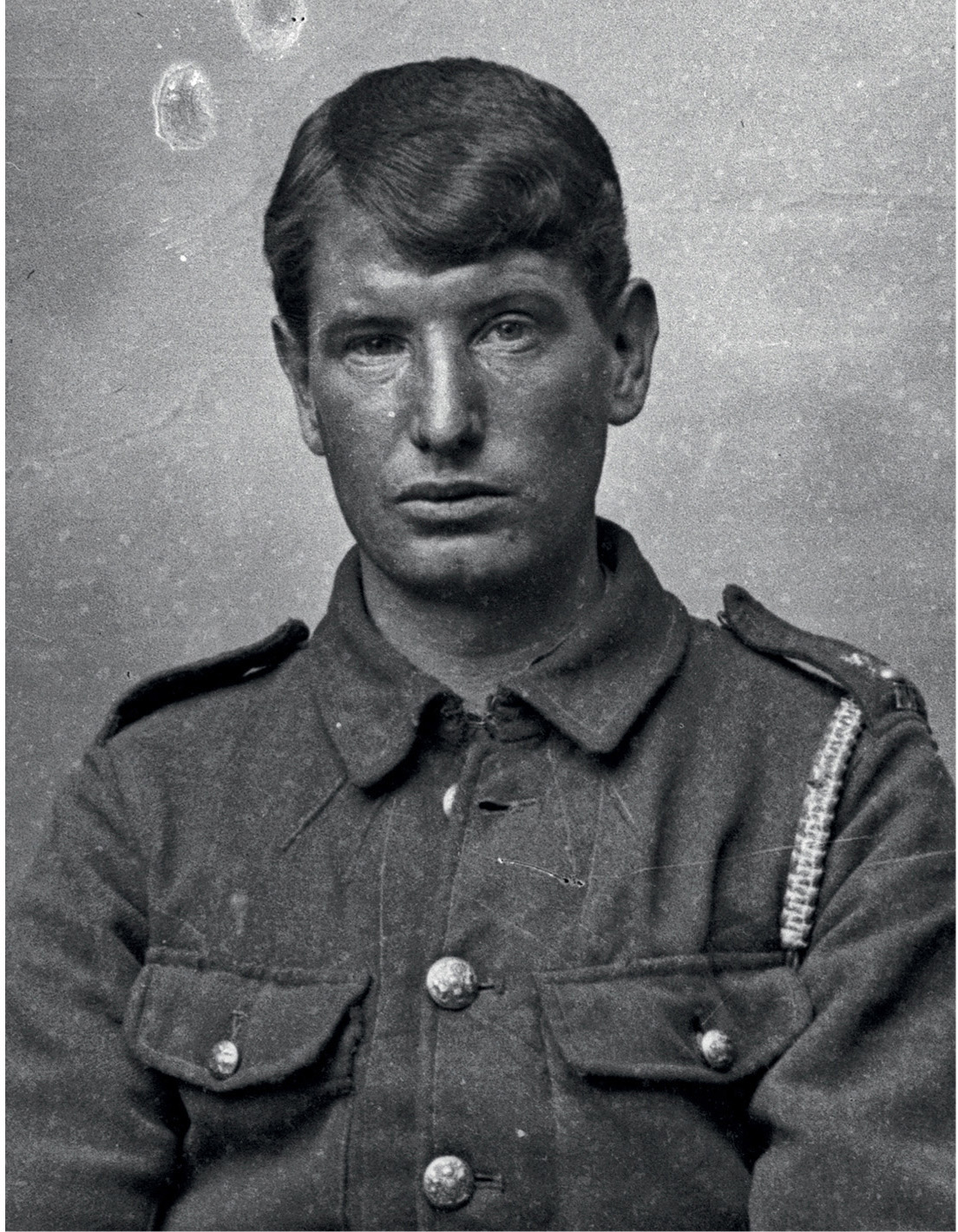

PLATE 36 A sad soldier of the Royal Fusiliers – a close-up from the high-resolution scan of his fatigued face shows him lost in thought. This same soldier also appears in Plate 216.

In February 2011, the Australian Channel Seven TV Network aired a documentary about the discovery of the Thuillier glass plates. Shortly after that ‘Lost Diggers’ story was broadcast, we posted thousands of the Thuillier collection photographs of the Allied soldiers on the programme’s website and also on a specially created Facebook page, which still exists today. It became an unprecedented social media phenomenon for a history archive, with millions viewing the pictures online from all over the world. Within days, the volume of emails, excited phone calls, letters and Facebook messages we were receiving showed just how much the images had touched so many. Hundreds of thousands of viewers wrote us emotional and passionate accounts of their response to the faces of the Australian diggers and British Tommies in particular:

Goose bumps watching the show …

This is so wonderful, I can barely believe it’s true. Many of the faces showed signs of great fatigue and yet they managed to smile and pose for a photo forever preserving the moment in time …

A few tears shed knowing some of these fellows never made it home. What a wonderful discovery for many families around the world.

For so many of the people who have since viewed the photographs online it has become a personal odyssey to find a connection with the as yet unidentified soldiers:

These photos brought tears to my eyes. I had eight great uncles who all fought on the western front. Five of them were brothers. One of them was killed in action five weeks before Armistice Day, after surviving three years of that bloody hell. He is our only Digger out of eight that we have no photographic record of. Maybe he is one of these men.

Thank you so much for making these great photographs available. My mother lost her uncle in France in 1915. We have no info’ on him, not even a photo. We have always tried to find his records but without a regiment number, we are up against a brick wall. I sit here with tears in my eyes, wondering if he is one of these brave men. You have done a wonderful thing.

Our grand uncle … died of wounds … How amazing to think his image could be among these photos.

I carefully examined each and every photo looking for any resemblance to the many family members who fought in WW1, some of whom never returned.

Then began the calls for the Australian images to be brought home:

Don’t let them be forgotten. Bring these historical plates to their rightful home.

These photos … should be treated as national treasures and every single one of them should be brought home immediately.

These young men gave their lives in order to protect and fight for our country; these photos are an amazing part of the history of Aussie diggers in battle and the campaign they were involved in … Lest we forget.

Many relics of these men may remain in France but these treasured photos need to be honoured on Australian soil. It is now our turn to answer the call of duty and return these photos to their home for safekeeping.

Ohh I have tears of pure joy and total sadness after looking through these pics … History in front of our very own eyes … Thank you for sharing. Never forgotten.

In July 2011, with the generous support of the Seven Network’s chairman, Kerry Stokes AC, the entire Thuillier collection of around 4,000 glass photographic plates, including the British images, was purchased from the living descendants of Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, the couple who had supplemented their farming income during the First World War by selling pictures to passing Allied soldiers. If Louis and Antoinette were alive today they would no doubt be chuffed and probably very surprised to see just how much passion their portraits of thousands of young soldiers from a war so long ago has aroused.

PLATE 37 An equally sad-looking soldier – no regimental badge.

In late 2011 the precious glass plates did finally ‘come home’, in a gigantic packing case, purpose-built to carry them, along with the Thuilliers’ canvas backdrop. After months of planning, cataloguing, careful cleaning and scanning, the Australian digger plates were gifted to the Australian War Memorial for permanent display. Many of the more intriguing images and the stories behind them formed the basis of a nationwide touring photographic exhibition organized by the AWM. The remaining thousands of British and other Allied soldier plates have been preserved by the Kerry Stokes Collection in a secure repository in Perth, Australia.

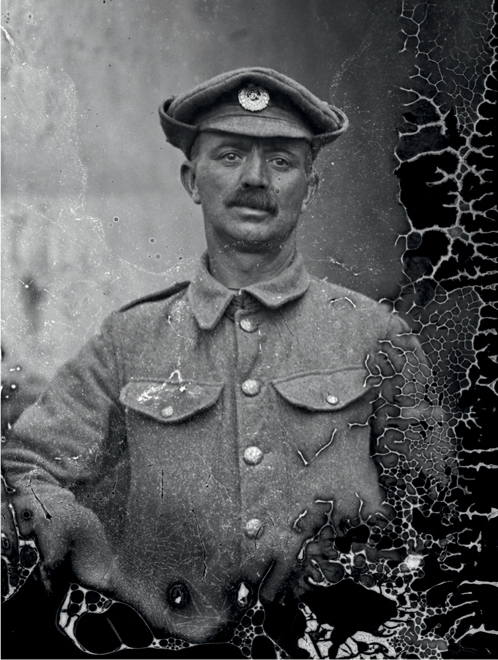

More than once in our research it has struck us how impermanent many of the records that we rely on today are in comparison with the handwritten files, letters, printed photographs and glass photographic plate negatives that have made this such a rich collection. As we began examining the plates, drawing on the expertise of people like Peter Burness, it was a revelation to discover how, in many ways, the photographic plates used by the Thuilliers are actually a superior storage medium to the standard celluloid photographic negative, let alone digital imaging. Not only have they already lasted nearly a century, but so much information is packed into these enormous negative plates that it was often possible for us to zoom in on a colour patch, medal ribbon or cap badge to help identify a soldier. There is something terribly poignant about being able to zoom in to the pained and weary eyes of an individual soldier – actually to see the mud on his boots and the texture of his uniform.

As we applied modern photo-processing software, it was astonishing to see faces emerge from the murk of so many plates – images that could so easily have been lost forever. We have asked ourselves many times how much of today’s history will survive to the same extent. How many personal handwritten letters have we preserved today that will record the thoughts and experiences of our loved ones for future generations to read? What was once recorded in a letter just a few decades ago is now just an electronic impulse stored on magnetic media whose lifespan can still currently only be surmised. Will the digital records of today – the photographs, emails and the writings on other online ephemera such as Facebook, Twitter and websites – allow people in a hundred years to explore the history of our present era with as many resources as remain from the First World War? How much of our heritage and experiences will be lost as contemporary storage media slowly fade or are carelessly deleted?