Полная версия:

Wagnerism

Redon once criticized Henri Fantin-Latour for producing “pale and soft sketches on the poems of the musician Wagner.” His own Wagner pictures are cryptic, unearthly, and—as Téodor de Wyzewa said in the Revue wagnérienne—“terrifying.” There are three of Brünnhilde. The first, which appeared in an 1885 issue of the Revue, is a lithograph of a boyish Valkyrie amid the fire of battle, her shield raised, her eyes wide with fierce concentration. The second, from 1894, shows a subdued warrior, her hair streaming in more feminine style, her face drawn into a mask of sadness. (Mallarmé owned a copy of this work.) Around 1905, Redon created a turbulent pastel in which Brünnhilde rides a dark purple horse that is rearing up into a sapphire sky. A mass of gold-brown brushwork could be either earth or fire. If this is the climax of Götterdämmerung, it is a coolly rapt vision of the world to come.

Redon’s two renderings of Parsifal are two decades apart and seem to span a lifetime. In a lithograph from 1891, the hero has large, dark eyes, a long, straight nose, and thin, determined lips, his left hand clutching a spear that looks more like a long arrow. The critic Ernest Verlant elaborated on the image: “His head is anointed, his feet sprayed with perfume; he has been crowned King of the Grail, master of august rites, initiate of Christ. Mystical promise is fulfilled in him; he is ‘the pure one, the holy soul rendered voyant through pity,’ and that is why his eyes widen in a supernatural fever and magnetize towards eternity.” A 1912 pastel of Parsifal provides a jolting contrast. This seems to be the transformed hero of Act III—the black-clad victor over Klingsor’s magic. His face is wrapped in a mass of flattened, brownish hair, with a stringy beard hanging down. There is something misshapen about the visage: the mouth is a sliver across the middle. No spear is visible. The figure seems hunched and tired, as if he is pausing in the middle of an interminable trek. The sky is a skirmish of light above a rocky outcrop. What unites this haunted sage with his younger counterpart is the wide-open sadness of the eyes, staring blankly into the future.

The Symbolists ran up against a quandary that was not unfamiliar to the man who founded the Bayreuth Festival: their excoriation of bourgeois mediocrity did not prevent the bourgeoisie from consuming their art. A vestige of Romantic mystery clung to the work of Khnopff, Delville, and Redon, making it suitable decor for wealthy salons. James Ensor, the chief rebel of Les XX, banished Symbolist aesthetics in favor of a brusque, bristling style that prophesied twentieth-century trends of Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and even Pop Art. Ensor made scathing caricatures of Catholic clergy, military brass, and financiers—the alliance that underpinned the ruthlessly exploitative regime of King Leopold II, the Belgian monarch. As the scholarship of Debora Silverman has made clear, the Art Nouveau splendor of Brussels depended on riches gained from the brutal colonial operation of the Congo Free State.

His habitual nonconformism notwithstanding, Ensor joined in the general veneration of Wagner. “This extraordinary genius influenced and sustained me,” he wrote. “I glimpsed a huge and beautiful world.” La Monnaie’s production of Walküre in 1887 apparently led him to paint a Ride of the Valkyries, in which the maidens ride over a tumultuously abstract landscape. An 1890 work is titled Indignant Bourgeois Whistling at Wagner in 1880 in Brussels. In the 1902 painting At the Conservatory, Ensor trains his ire at the bourgeois culture that consumes Wagner without comprehending his deeper meanings. An elegantly attired singer performs from a score whose cover is imprinted with a garbled version of Brünnhilde’s cry: “HO.Y.HOTOYO / HO Y HO HO / HAUT Y HAUT / TROP HAUT / TROP PEAU …” (“too high, too skin”). She is being pelted with flowers, a cat, a duck, and a pickled herring. In the midst of this fiasco, Wagner himself is seen holding his fingers to his ears.

Ensor’s most celebrated work is the enormous—almost Wagnerian—Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889. It is a phantasmagoric vision of the Savior riding a donkey through a carnivalesque throng, with a wooden-soldier brass band at the center and a bloated bishop at the front. In Patricia Berman’s reading, the painting condemns Leopold’s Belgium for its abuse of Christian iconography in the service of state violence. Originally, Ensor intended to include Wagner in the nightmare procession: a preparatory drawing from 1885 has at its center a banner reading “PHALANGE WAGNER FRACASSANT,” or “Wagner Army Raising a Din.” The same legend appears in a later copper etching. Is this a band of anti-Wagnerians, denigrating the Bayreuth master as a purveyor of mere noise? Or are Belgian Wagnéristes themselves the butt of the satire—revering the composer of Parsifal while travestying the Redeemer’s message? Ensor gave no evidence of his thinking, and in the final painting he omitted the “PHALANGE” banner, probably by painting over it. Wagner is drowned out by the urban din, the savage parade.

SATANIC WAGNER

Péladan spoke of “sathanisme de l’amour.” Baudelaire invoked a “satanic religion.” Huneker beheld a Black Mass in Parsifal. The idea that Wagner’s music tapped into devilish forces had wide purchase, both among the composer’s detractors and among his wilder-eyed disciples. Fin-de-siècle culture granted mighty powers to artists, and by some accounts Wagner was capable of administering a sort of aural potion of death or derangement.

The supernaturally inclined could point to a string of mishaps that befell people close to Wagner. The tenor Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld dropped dead shortly after creating the title role of Tristan, in 1865. His widow, the soprano Malvina Garrigues, who was the first Isolde, received mediumistic messages from Schnorr and accused Cosima of being an “infernal spirit.” Alois Ander, who had earlier rehearsed Tristan in Vienna, died insane in 1864. Felix Mottl suffered a fatal heart attack while conducting Tristan in 1911. Ludwig II died a watery death in 1886. The Russian-Jewish pianist Joseph Rubinstein, a fanatical follower, killed himself in 1884, supposedly in despair over the Meister’s passing. The Polish pianist and composer Carl Tausig, also Jewish, died of typhoid at twenty-nine; some blamed the strain of serving Wagner. Nietzsche crossed the border into madness while raving about Richard and Cosima. On the other hand, Cosima herself lived to the age of ninety-two.

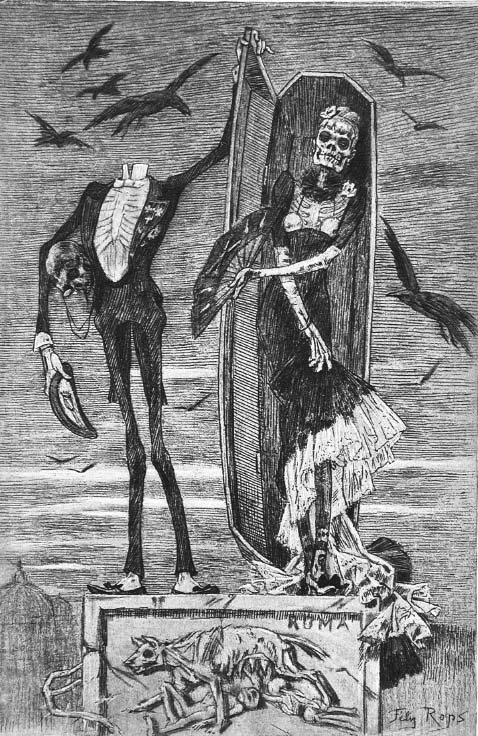

Félicien Rops, frontispiece for Péladan’s Le Vice suprême

Wagner saw himself as an affirmative artist, preparing humanity for a better world. Yet he, too, sensed danger in his music. While composing Tristan, he worried that it would drive people insane. After Schnorr’s death, he wrote in his diary: “My Tristan! My beloved! I pushed you to the abyss!” (The salutation quotes Kurwenal, Tristan’s friend and servant.) Undeniably, there is a romance of evil in Wagner. Venus, in Tannhäuser, bewitches the ears, especially in the Paris version of 1861. Telramund and Ortrud, the malefactors of Lohengrin, hatch their plots over jagged, corkscrewing figures that announce Wagner’s mature style. Alberich and Hagen, in the Ring, stride grandly in the bass regions. Conversely, paeans to goodness in the operas are not always convincing. Siegfried’s Funeral Music is more impressive than the man himself. Parsifal’s wound-closing monologue often sounds a touch hollow. Suffice to say that evil is necessary in Wagner’s world, and the division between evil and good is fluid.

Fin-de-siècle fiction feasted on Wagner’s macabre side. An early instance is Élémir Bourges’s 1884 novel Le Crépuscule des dieux, whose title is the French name for Götterdämmerung. Bourges, a member of Péladan’s Rose + Croix order, tells of a great old family in decline—a popular story arc of the period. A German notable named Charles d’Este, Duke of Blankenbourg, is introduced as the “son of a race of gods.” He is marking his birthday by hosting Wagner in a command performance. During Act I of Walküre, the duke learns that Prussian troops have entered his territory, and he is forced to flee. As he departs, the composer solemnly informs him that the Ring will end with a Twilight of the Gods. Decadence infects the family, sowing death and madness. A scheming Wagner soprano named Giulia Belcredi, having become the duke’s mistress, plots to destroy two of the duke’s children, the half-siblings Hans Ulric and Christiane. Belcredi convinces the duke to host a domestic performance of Walküre, with Hans Ulric and Christiane cast as Siegmund and Sieglinde. She knows, somehow, that Wagner’s drama will trigger incestuous love in the real-life pair. When it does, Hans Ulric kills himself and Christiane enters a convent. At the end, the duke falls ill, attends Götterdämmerung at Bayreuth, and dies.

As the eighties gave way to the nineties, vampiric, necromantic, and satanic themes proliferated in post-Wagnerian, post-Symbolist literature. Joris-Karl Huysmans set the tone with a series of novels that began with À rebours, in 1884, and continued with En Rade (1887) and Là-bas (1891). Against a backdrop of hyper-refined aestheticism, Huysmans exposed his readers to homosexuality, incubi and succubi, sadism, the child murders of Gilles de Rais, the Black Mass, and, most exotically, a Mass of Sperm. Huysmans adroitly placed this ghastly subject matter in the context of a wide-ranging spiritual search; in the end, he and his protagonists return to traditional Catholicism. “From exalted mysticism to raging Satanism is but a step,” a character says in Là-bas. “In the beyond, all extremes meet.”

“The Succubus,” an 1898 story by the Belgian writer Camille Lemonnier, is in the Huysmans mold, and also harks back to Poe and E. T. A. Hoffmann. It opens at a performance of Tristan somewhere in Bohemia. The narrator cannot take his eyes off a deathly pale woman in a neighboring box, who, he senses, has some connection to his past life. The sight of this “satanic perversity” harmonizes with Wagner’s “torrent of love and sadness,” his “symphony of afflictions.” During Act III, the narrator remembers what happened. In his youth, when he was bedridden with a near-fatal illness, a woman had visited him, clad only in red and black ribbons.

This devouring virgin penetrated under my sheets and bit my lips with so fearful a kiss that my blood immediately gushed a large jet. Our bodies immediately convulsed; mine, in my effort to escape her, writhed like a wounded slow-worm; and at the end I stopped repulsing her deadly thirsty lips. While in small strokes she continued to lick my red substance, I myself drank life at her neck, under the black ribbon, as from a fountain … My mother, entering my room in the morning, found me half expired and bathed in my own blood.

When the lights go up, the narrator rushes to the exits, but “the Lady with red headbands, like a lithe phantom, like the vampire that she was, seemed to have dissolved in the air of the street.”

In Latin America, the Modernismo movement, led by the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío, mixed Symbolist, Decadent, and Wagnerian strains, to sometimes creepy effect. Horacio Quiroga, a Uruguayan epigone of Poe, wrote two stories on Wagner subjects: “The Death of Isolde” and “The Flame,” also called “Berenice.” The second is set largely in Paris in 1842, and features Wagner and Baudelaire as characters. Baudelaire introduces the composer to a wealthy patron and her ten-year-old daughter, Berenice, who shows signs of being enraptured by Wagner’s music. The score of Tristan is tried out with orchestra. Wagner feels the child throbbing beside him, and is surprised to discover that she has suddenly grown older: “Those twenty minutes of hurricane-force passion had just converted a child into a woman radiant with youth, eyes darkened in mad fatigue.” As the opera progresses, the aging process advances at terrifying speed, until Berenice has become a decrepit, cataleptic old woman. She remains in that condition until her death, forty years later. In the face of such poetic license, it seems pointless to add that Wagner did not know Baudelaire in 1842, nor did Tristan exist.

The apogee of satanic Wagnerism is, arguably, Marcel Batilliat’s 1897 novel Chair Mystique, or Mystic Flesh. Schooled in Zola and Huysmans, Batilliat adopted a style at once precise and precious. Mystic Flesh, which has a notation from Tristan as its epigraph, tells of a young woman named Marie-Alice, who, trapped in a provincial life, is drawn to the literature and music of high passion. She dreams of “reviving the divine loves of the Wagnerian heroes,” of becoming the “modern Isolde” to a “modern Tristan.” Her mother died of tuberculosis, and she is fated to perish of the same disease. Her knight in black armor is an alienated aesthete named Yves. They form a bond as Marie-Alice plays Tristan at the piano, the odor of death rising around her. Moving to an isolated forest house, they lose themselves in an oblivion of love. Marie-Alice falls sick, and a doctor friend warns Yves of infection. Instead, Yves hurls himself into prolonged bouts of lovemaking, in the hope that he will contract the disease. On breaks, the lovers read the Symbolists and “adore above all the sublime pages of Tristan und Isolde.” A stray cat joins the ménage and acquires the name Klingsor. Eventually, poetry bores them; only music matches their delirium. Marie-Alice dies in Yves’s arms, her last throes resembling orgasm. They remain entangled as rigor mortis sets in.

But this is not all. Marie-Alice is buried, and Yves, now falling ill himself, has a dream in which he sees his lover’s corpse approaching him. Batilliat abruptly switches stylistic gears, using the kind of hyper-clinical language favored by naturalist writers:

She was naked as on their nights of love, and all green amid a swarming of parasitic worms! Everywhere, ocher, amber, and slate-gray emphysemes stretched the integuments; a purulent, brownish fluid exuded through the pores, flowed from natural openings which were full of larvae and worms. On the depressed thorax, whose ribs were bursting the skin, serous vesicles contrasted in their paleness with red plaques that marked the place of the intestines, and the ruptured abdominal walls, scarred by a huge wound, gave out their putrid contents, all twitching with the activity of roundworms. The eyes were black holes, where oozing brain matter turned into pus; bared teeth, stained with purulence, laughed a horrible laugh, between saponified muscles and blueish aponeurosis. Alone among all these horrors, the golden hair, flowing like a scarf as on the day of farewell, had remained resplendent, like a streaming of light.

Even in the wake of this magisterially revolting hallucination, the Tristan fantasy lingers. At the very end, Yves again salutes the operatic pair, “who loved each other as one must love: to the utmost!” Indeed, with his scene of eroticized decomposition, Yves has set a new outer limit of Wagnerian passion—one that will have no serious rival until the 1960s, when Yukio Mishima filmed an act of seppuku to the tune of Tristan.

THEOSOPHY

The Goetheanum, Dornach

Helena Blavatsky, the chief figure in Theosophy, did not care at first for Wagner. In 1883, she had this to say about Parsifal: “Such a handling of the ‘most sacred truths’—for those for whom those things and names are truth—is a sheer debasement, a sacrilege, and a blasphemy.” Four years later, Madame Blavatsky, as she was widely known, suffered a near-fatal medical crisis, and formed a good opinion of the doctor who treated her—William Ashton Ellis, the indefatigable and fatiguing English translator of Wagner’s prose. Ellis had embraced Theosophy in the mid-eighties, around the time he began writing about the composer. Almost at once, Theosophical opinion turned around. In 1888, Blavatsky’s magazine Lucifer—the title denotes the bringing of light, not Satan—warmly greeted Ellis’s Wagner journal, The Meister, saying that Wagner was a “mystic as well as a musician” who “penetrated deeply into the inner realms of life.”

Ellis was right to see common ground between Wagner and Theosophy. Blavatsky’s synthesis of West and East resembles the religious fusion of Parsifal, although she gives stronger emphasis to Eastern thought, especially Buddhism. The daughter of a Russian military officer, Blavatsky traveled widely in her youth, gaining a reputation as a psychic. She claimed to have received telepathic communications from a group calling themselves the Mahatmas, or super-evolved Masters. In 1873, she showed up in New York, where she began to elaborate her Secret Doctrine. Disavowing spiritualism, she defined Theosophy not as a religion but as a rational inquiry into religion, a “purely divine ethics.” She was not above using cheap tricks to soup up her legend. An 1885 investigation by the Society for Psychical Research concluded that Blavatsky was “one of the most accomplished, ingenious, and interesting imposters of history.” She plowed ahead regardless, and by the time of her death, in 1891, Theosophy had become international in scope, its headquarters based in Adyar, India.

In 1888, Lucifer published Ellis’s essay “A Glance at Parsifal?,” which interprets Wagner’s Grail as “the Divine Wisdom of the ages, the Theosophia which has been ever jealously guarded by bands of brothers.” It abides in a place “whence Time and Space have fled away.” The titular hero “unites in his nature the characteristics of Jesus Christ and Gautama Buddha.” Brotherhood heals the world’s discords. The message of the opera, Ellis says, is acutely relevant “in these days when each man’s hand is turned against his brother, when materialism is rife … and each state in Europe, laughing at [religion’s] shrill, unmeaning bleat, adds another fifty thousand paid butchers to its bloated armaments!”

Although Ellis soon withdrew from active involvement in Theosophy, other Wagnerites took his place. In 1896, Basil Crump, a barrister who specialized in maritime law, began publishing pamphlets analyzing the Wagner operas as composites of religious traditions. He was soon joined by Alice Leighton Cleather, a clergyman’s daughter who belonged to Blavatsky’s circle. Together, Crump and Cleather published four studies of the Wagner operas. In Parsifal, they write, “the essential elements of the great religions of the Eastern and Western worlds—Christianity and Buddhism—are blended in a form especially adapted to the Western world of to-day.” Tristan, too, acquires an Eastern tinge. Crump and Cleather label a phrase from the prelude the “Nirvâna motive” and link it to the “redeeming power which shall bring peace and rest in the bosom of the Oversoul.” When Cleather visited Bayreuth, she was pleased to see many Eastern texts in the Wahnfried library.

In the mid-nineties, a group of American Theosophists split from Blavatsky’s heir apparent, the British socialist and anti-imperialist Annie Besant, to form the Theosophical Society in America. They were under the sway of Katherine Tingley, a social worker from an obscure background, possibly theatrical. Grandiose in manner, habitually wrapped in robes and scarves, Tingley announced a World Crusade, in the hope of gaining a global presence for the American wing. In an essay on Theosophical Wagnerism, Christopher Scheer notes that excerpts from the music dramas were often heard at Tingley’s events. In 1897, the Third Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society in America, at the Madison Square Garden concert hall, opened, Péladan-style, with Parsifal on the organ.

For a few years, Crump and Cleather participated in Tingley’s movement, perhaps lured by its Wagnerian trappings. In 1897, they traveled to North America and lectured on Wagner and Theosophy, drawing crowds of up to a thousand people in halls bedecked with the flags of Tingley’s Crusade. Musical examples were played, though in modestly scaled arrangements. In keeping with the Bayreuth idea of the invisible orchestra, the musicians remained hidden behind a screen. Journalists made much of the duo’s penchant for high-tech illustrations: magic-lantern images of Lohengrin, the Flying Dutchman, Parsifal, and other Wagner heroes flickered before audiences’ eyes. Crump happily concluded: “The new aspect of Theosophy presented in these musical lectures has proved very attractive and has interested a new section of the public who are ready for the message but needed touching in a different way.”

The World Crusade had a destination in view: Point Loma, California, a Theosophical utopia outside San Diego, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The complex included a Temple of Peace, the Raja Yoga Academy, and an open-air Greek theater. On seeing it, the actor Helena Modjeska exclaimed, “A second Bayreuth!” Nellie Melba said that the scene reminded her of her first experience of Parsifal. A group of Parsifal paintings by the Theosophical artist Reginald Machell, an Englishman who had settled in Point Loma, exemplified the Tingley vision; in two of them a guru-like figure holds the Grail over his head, his arms forming a sacred geometry with the cup. “Every conqueror of himself conquers also for others,” Machell explained.

Reginald Machell, The Holy Grail

Like the Rosicrucian sects of Paris, branches of Theosophy kept feuding with one another and engaging in doctrinal warfare. When Annie Besant anointed an Indian boy named Jiddu Krishnamurti as a Messiah figure, the German Theosophist leader Rudolf Steiner left the society, taking much of German Theosophy with him. In 1912, he formed his own discipline, Anthroposophy, which has endured longer than most fin-de-siècle spiritual movements. Hundreds of Waldorf schools around the world follow Steiner’s philosophy of holistic education, fostering creativity and independence in children. More intellectually rigorous than many in the Theosophical world, Steiner was well grounded in philosophy, science, and socialism. Intolerant of Theosophy’s Eastern slant, Steiner focused on the Western mystical heritage, with particular attention to tales of the Grail. He directed Munich productions of Édouard Schuré’s spiritual dramas, The Sacred Drama of Eleusis and The Children of Lucifer, and wrote his own mystery plays, which, in the words of one acolyte, represented “the psychic development of man up to the moment when he is able to pierce the veil and see into the beyond.”

Steiner joined Schuré, Ellis, and others in sensing a “strange and deep connection” between Wagner and the new spiritual trends. In the eighties, in Vienna, he encountered rabid young Wagnerites, whom he characterized as “homeless souls,” hungry for an alternative to materialist modernity. In 1905, he gave four lectures on the topic “Richard Wagner in Light of Spiritual Science,” and two years later, having seen Parsifal in Bayreuth, he spoke about Wagner and mysticism. Following Schuré, Steiner framed the operas not as psychological dramas but as treatises on initiation, on the overcoming of mundane reality. Thus, Isolde’s Transfiguration evokes the union of souls in an astral world—a “surging ocean of bliss” removed from ordinary sexual desire, indeed from the division of gender itself. Dwelling on Parsifal, which he sometimes used as entrance music for his lectures, Steiner predicts that the human reproductive organs of the future “will not be infused with desire, but will be pure and chaste, like the plant-calyx that turns itself toward the love-lance, the ray of sunshine.”