Полная версия:

Wagnerism

Wagner blended readily with the mystical milieu. Édouard Schuré, a leading French explicator of arcane practices and non-Western religions, acclaimed him as “a fallen Lucifer” and “the greatest unconscious occultist who ever lived.” Gérard Encausse, who took the pseudonym Papus and co-founded the modern Martinist order, said that “the world of enchantments has confided all of its secrets” to Wagner. Rudolf Steiner, the leader of Anthroposophy, declared: “That there is in Wagner and in his works a very large measure of occult power, is something that mankind is gradually learning to realize.” In 1901, Aleister Crowley, the British magus, addressed the composer thus:

O MASTER of the ring of love, O lord

Of all desires, and king of all the stars,

O strong magician …

Crowley asserted that Parsifal had been created at the bidding of the German occultist Theodor Reuss, the Outer Head of the Ordo Templi Orientis, or Order of Oriental Templars. Wagner’s name appears on a fantastical list of members of the order, alongside Siddartha, Osiris, Orpheus, Mohammed, Merlin, Dante, Goethe, and Nietzsche.

The quest for mystical truth produced reams of nonsense, but it also inspired thrilling imaginative leaps—indeed, some of the earliest feats of artistic modernism. Michelle Facos and Thor Mednick, in The Symbolist Roots of Modern Art, describe how the Symbolists undermined conventional modes of representation in an effort to “access the divine directly.” John Bramble, in Modernism and the Occult, notes that artistic avant-gardes often patterned themselves on the esoteric orders of the day, sometimes becoming indistinguishable from them. Art in the cultic mode, which would persist deep into the twentieth century, had no greater exemplar than the Sorcerer of Bayreuth.

ROSE + CROIX

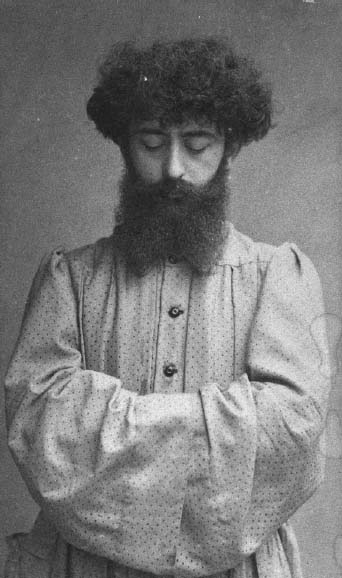

Joséphin Péladan

After Wagner’s death, Bayreuth faced an uncertain future. Parsifal drew less than full houses in 1883 and 1884—a sign the festival could not subsist on one work alone. When Cosima Wagner assumed control, she expanded the repertory, adding Tristan in 1886 and Meistersinger in 1888. By the end of the decade, the festival had found a steady footing. Cosima, an Italian-born French-Hungarian who spoke fluent German and English, knew that Bayreuth’s future depended on an international audience, and she proved adept at obtaining one. The guest lists for 1888 included the composers Giacomo Puccini, Ferruccio Busoni, Max Reger, and Johann Strauss, Jr.; the rising musical revolutionary Claude Debussy, who occasionally visited occult circles; a raft of eminent Bostonians, including Isabella Stewart Gardner and Bernard Berenson; Édouard Dujardin and Houston Stewart Chamberlain, of the Revue wagnérienne; the photographer Alfred Stieglitz; the architect and stage designer Adolphe Appia; and the Symbolist painter Fernand Khnopff.

Conspicuous in the crowd that summer was Joséphin Péladan—novelist, playwright, art critic, and performance artist avant la lettre. Péladan habitually went about in a flowing white robe, an azure or black velvet jacket, a lace ruff, and an Astrakhan hat, which, in conjunction with his bushy head of hair and double-pointed beard, gave him the look of a Middle Eastern potentate. Perhaps on account of that costume, he failed to gain admittance to Wahnfried, but he became a fervent Wagnerite all the same. Three hearings of Parsifal, he later said, led him to his calling as a Rosicrucian mage: “The renovation of the Rose + Croix was born at Bayreuth, was born of Bayreuth!” Although he had doubts about the festival, he cherished it as a place free of cynicism, where “one goes in search of emotions and not epigrams.” If not for the German language, he said, it would be the loveliest place on earth.

Péladan was born in Lyon, in 1858, into a family steeped in esoterica. His father, Louis-Adrien, was a conservative Catholic who tried to establish a Cult of the Wound of the Left Shoulder of Our Savior Jesus Christ. Péladan’s older brother, Adrien, wrote a medical text describing how the brain subsists on unused sperm that takes the form of vital fluid. When Adrien died prematurely, of accidental strychnine poisoning, his brother propagated his ideas, arguing that the intellect can thrive only when the sexual impulse is suppressed. The Péladans were reactionary in their politics, detesting democracy and demanding the restoration of the monarchy. Péladan differed from many other occultists in couching his Rosicrucian rhetoric as an extension of authentic Catholic doctrine.

He made his name first as an art critic, inveighing against naturalism and Impressionism, both of which he considered banal. “I believe in the Ideal, in Tradition, in Hierarchy,” he said. His model painter was Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who, in a manner akin to Pre-Raphaelitism, rendered neoclassical subjects in archaic style, flattening perspectives and whitening colors. “What he paints has neither place nor date,” Péladan wrote of Puvis. “It is from everywhere and always.” At the same time, he had a taste for the lurid, enjoying the nastily glittering Salomé pictures of Gustave Moreau and the gruesome caricatures of Félicien Rops. Péladan singled out for praise Rops’s Les Sataniques, etchings of visibly aroused demons penetrating and killing women. Such pendulum swings between piety and depravity were typical of the fin-de-siècle milieu.

In 1884, Péladan published his first novel, Supreme Vice—the initial installment in what turned out to be a twenty-one-volume cycle titled La Décadence latine. A magician named Magus Mérodack is pitted against embodiments of decadent society, notably the domineering, sphinxlike Princess Leonora d’Este. A flagrant misogynist, Péladan often saw women as vessels of satanic energy. He attributed to Rops the saying “Man puppet of woman, woman puppet of the devil.” Supreme Vice had a considerable success, despite its obscure and inconclusive narrative. Crucially, it caught the eye of the poet Stanislas de Guaita, who began exchanging ideas with Péladan about the restorative capacity of magic. By the time Péladan arrived in Bayreuth, in 1888, he had joined forces with Guaita to form a Rosicrucian society called the Kabbalistic Order of the Rose + Cross.

Mystical circles were prone to constant internecine warfare, and even the smallest sects found ways to subdivide into still tinier ones. By 1890, Péladan and Guaita were parting ways, mainly over Catholic doctrine: the one adhered to strict beliefs, the other inclined more toward Kabbalism, Buddhism, and paganism. (Guaita’s thinking was actually closer to the syncretism of Parsifal, though he showed little interest in Wagner.) Péladan proceeded to found the Order of the Catholic Rose + Croix of the Temple and the Grail, dubbing himself Le Sâr Péladan, after the Akkadian word for “king.” He published a book titled How One Becomes a Mage, and let it be known that he had completed the syllabus. He informed Félix Faure, the president of the Republic, that he had the gift of “seeing and hearing at the greatest distance, applicable to enemy councils and suppressing espionage.” To the Minister of Public Instruction and Beaux Arts, he wrote that he had “reforged Nothung.” He began one lecture by saying, “People of Nîmes, I have only to pronounce a certain formula for the earth to open and swallow you.”

Péladan’s trip to Bayreuth yielded a novel titled The Victory of the Husband, the sixth book in the Décadence cycle. The preface offers “greetings and glory to you, Richard Wagner, thaumaturge and discoverer of the third mode, conqueror and emperor of the Western Theater!” The plot concerns the love of Izel and Adar: she, the adopted daughter of a wealthy Avignon priest; he, a young genius aghast at the stupidity of his time. They speak “in Wagner,” styling themselves Siegmund and Sieglinde. When they honeymoon at Bayreuth, one of the more stupefying Wagner Scenes in literature ensues. During a performance of Tristan, the newlyweds cannot restrain themselves and begin making love. “Tristan! Isolde!” the lovers cry onstage. “Adar! Izel!” the lovers murmur in the audience, possibly to the irritation of their neighbors. As their lips lock together, there is a salty taste of blood.

On the question of Parsifal, however, the lovers diverge. For Izel, the opera is too “chaste, sweet, and calm.” For Adar, it opens the door to a new mystic consciousness. He goes to study with a sinister Nuremberg sorcerer named Doctor Sexthental and drifts away from his bride. Sexthental, sensing an opportunity, projects himself astrally into Izel’s chambers, in the form of an incubus. The initiate defeats this incursion, but marital strife persists. Adar must renounce his magic—“I resign the august pentacle of the Macrocosm”—to regain Izel’s love.

Wagner figures in various other Péladan novels. In Le Panthée, a starving composer stoops to playing piano at a resort; when he is told that his choice of Tristan is agitating the clientele, he defiantly launches into Siegfried’s Funeral Music. In The Androgyne, an angelically feminine thirteen-year-old boy improvises on Beethoven and Wagner, “sounding the bells of the Grail after a phrase from the Pathétique Sonata.” And in The Gynander, another androgyne, Tammuz, makes it his mission to convert “gynanders”—Péladan’s term for lesbians—to heterosexuality. His final triumph comes when he performs the feat of generating replicas of himself, each of whom seduces and marries a wayward lesbian. As an orchestra plays the wedding march from Lohengrin and music from Walküre, the brides fall to worshipping a giant phallus. Thus summarized, Péladan’s writing sounds daft. But it is impressively daft, and had many admirers in its day. Anatole France, Paul Valéry, André Gide, and André Breton read him with pleasure. Verlaine called him “bizarre but of great distinction.”

In 1892, Péladan found a new identity as an artistic impresario, inaugurating the Salons de la Rose + Croix. The intermingling of the arts at these annual affairs—painting, sculpture, theater, music—anticipated the mixed-media happenings of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. John Bramble goes so far as to say that the Salon pioneered the “religion of modern art.” What Péladan took from the “superhuman Wagner” was, above all, the idea that the artist should be “a priest, a king, a magus.” At the Salon, Péladan wrote, “there will unfold intellectual rites as noble as the celebrated ones at Bayreuth … The Ideal will have its temple and its knights.” The opening ceremony was to have taken the form of a Solemn Mass of the Holy Spirit at St.-Germain l’Auxerrois, with excerpts from Parsifal sounding on the organ. Wary clerics withheld permission, on the grounds that Wagner was Protestant. So Péladan and his cohort repaired to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, where they held aloft a rose crossed with a dagger, to the bafflement of ordinary parishioners. At the exhibition itself, which occupied the Galerie Durand-Ruel, brass players intoned the Parsifal prelude.

The Salons continued annually until 1897, attracting large crowds and voluminous commentary. Such luminaries as Mallarmé and Verlaine paid their respects. Yet Péladan never won the confidence of the artistic community at large. He alienated several leading figures, including Puvis, by prematurely advertising their participation. The end result was a somewhat indiscriminate mix of stylistic schools and levels of accomplishment. Péladan complicated his task by issuing strenuous restrictions and regulations. He forbade history paintings, still lifes, seascapes, “everything humorous,” and “all representations of contemporary life, whether private or public.” (Lest anyone miss the anti-naturalist agenda, a poster for a later Salon showed a Perseus-like hero holding up the severed head of Émile Zola.) Architectural entries were discouraged, “that art having died in 1789.” Female artists were ostensibly excluded, “following Magical law,” although at least five women exhibited under pseudonyms—including the arch-Wagnériste Judith Gautier, who contributed a relief sculpture titled “Kundry, Rose of Hell.”

In the midst of the first Salon, Péladan feuded with his chief financial supporter, Antoine de La Rochefoucauld, who held the title of Archonte des Beaux-Arts. The point of contention was Péladan’s play The Son of the Stars, which told of a shepherd-poet being initiated as a magus. The Montmartre composer Erik Satie wrote astonishing, borderline-atonal music for the premiere—another instance of mystical impulses leading into uncharted regions. When La Rochefoucauld decided to cut back on Salon events, including two performances of The Son of the Stars, Péladan proclaimed a schism and arranged a disruption of a concert that remained on the schedule—a Wagner program conducted by Charles Lamoureux. During the Siegfried Idyll, an ally of Péladan’s, ineffectively disguised by a thick beard, began shouting imprecations, calling the Archonte “a felon, a coward, a thief.” The heckler was ejected, causing a glass door to shatter and the musicians to fall silent. Cries of “Vive Péladan!” were drowned out by “Vive La Rochefoucauld!” Somehow, the concert proceeded to its close—the final scene of Parsifal.

Péladan’s notoriety dwindled as the nineties went on. Satirists reduced him to caricature: Jean de Tinan’s 1897 novel Mistress of Aesthetes features a Grand Master Sotaukrack, author of The Sphinx with Mauve Eyes. By the time of his death, in 1918, Péladan seemed a perfumed relic. Still, he was never forgotten, his influence surfacing in unexpected places. Ezra Pound consulted Péladan’s The Secret of the Troubadours; Wassily Kandinsky cited Le Sâr’s dictum that “the artist is a ‘king’ … not only because he has great power, but also because his responsibility is great.” Later in the century, Joseph Beuys read Péladan with interest. What caught these artists’ attention was Péladan’s faith in the alchemy of the creative act. In 2017, the much-mocked magus received belated vindication in New York, as the Guggenheim Museum, housed in Frank Lloyd Wright’s upward-spiraling modernist temple, presented a re-creation of the Salons de la Rose + Croix. Fittingly, Parsifal emanated from the loudspeakers.

BRUGES-LA-MORTE

In his headiest moments, Le Sâr imagined that he could make the world of the Grail real. He spoke of a “Monsalvat restored”—some solitary, ruined abbey that would be consecrated for his order, its walls ringing with strains of Aeschylus, the Ninth Symphony, and Titurel’s funeral music. During a visit to Belgium, where his ideas intrigued local artists and writers, Péladan was told that a wealthy American had offered to donate an old church as the site for a new Grail Temple. If his account is to be believed, and most likely it is not, Péladan was returning from Brussels to Paris to meet with the supporter, Parsifal resounding in his head, when customs inspectors confronted him at the border. They sized up his exotic dress—the hat, the boots, the cloak—and deemed him unhygienic. When an undeclared package of Egyptian cigarettes was found in his luggage, Péladan was detained for some hours, missing the assignation with the mysterious American. “Wagner alone suffered such hatred,” he wrote.

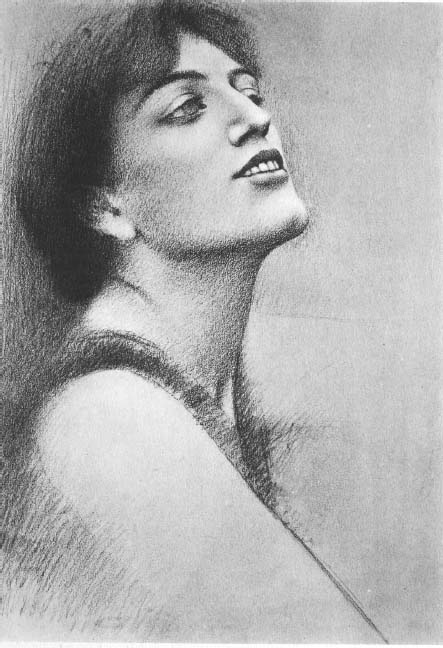

Fernand Khnopff, Isolde, 1905

Belgium would have been a logical place for a new Monsalvat, since the nation was to some extent an operatic creation. In the summer of 1830, the revolutionary overtones of Daniel Auber’s opera La Muette de Portici, a work that Wagner appreciated, incited riots during and after a performance at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, the venerable opera house of Brussels; those riots are credited with setting off the Belgian Revolution, which led to independence from Dutch rule. La Monnaie was later the site of one of Europe’s staunchest Wagner cults. Performances of Lohengrin held particular attraction, since that opera is set in the vicinity of Antwerp. It received its Belgian premiere in 1870, long before it arrived in Paris. In the years when Wagner was still scarce in France—only in the nineties did his operas begin to enter the repertory—intellectuals often traveled to Brussels to hear what they were missing.

As the sinuous lines of Art Nouveau mingled with centuries-old Gothic and Baroque architecture, Belgian cities took on a dreamlike air. By night, they could be mistaken for opera sets. Such is the mood of Georges Rodenbach’s 1892 novel Bruges-la-morte, or Bruges the Dead, in which the paralyzed sorrow of the widowed protagonist is of a piece with the town’s ascetic, brooding atmosphere. The Belgian architects and designers who helped to invent Art Nouveau often mined Wagner for ideas. Henry van de Velde, a harbinger of modernist design, set himself the goal of making a Gesamtkunstwerk out of the domestic sphere. The art historian Katherine Kuenzli writes that van de Velde’s fastidiously harmonized Bloemenwerf villa, on the outskirts of Brussels, “shifted the setting for aesthetic experience from the mythical stage of Wagner’s festival theater at Bayreuth to the realm of everyday life.”

An atmosphere of withered medieval romance pervades the work of Maurice Maeterlinck, the most renowned Belgian writer of the period. Although Maeterlinck was confessedly ignorant of music, he knew Wagner’s librettos and took Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s Axël as a model. Maeterlinck’s 1892 play Pelléas et Mélisande, immortalized in operatic form by Debussy, shares traits with Tristan and Parsifal. It is a tale of forbidden love set in a decaying kingdom, with the enigmatic, Kundry-like Mélisande emerging from a Symbolist forest. Maeterlinck’s people, in contrast to Wagner’s, are aggressively depersonalized, at the mercy of nameless fates. Maeterlinck once wrote: “It may be necessary to remove the living being entirely from the scene.”

The leading Belgian art journals, like their French counterparts, named Wagner as a fellow combatant in the war against bourgeois taste. The progressive periodical L’Art moderne wrote of a “valiant Wagnerian army” doing battle with ignorance, indifference, and routine. In 1883, the critic Octave Maus, co-founder of L’Art moderne, took the lead in organizing Les XX, or the Twenty, an artistic alliance whose original roster included Fernand Khnopff and James Ensor. They were later joined by Rops, van de Velde, and two sympathetic Frenchmen, Paul Signac and Odilon Redon. With the exception of Rops, all were Wagnerites, and Khnopff was the most avid of the lot.

A child of the haute bourgeoisie, Khnopff spent part of his youth in Bruges, absorbing the city’s timeless atmosphere. He later provided the frontispiece for Bruges-la-morte—an Ophelia-like figure floating amid weeds on a canal. Having made his name as a society portraitist, Khnopff ventured into the Péladan circle in the mid-eighties. Supreme Vice enjoyed a Belgian vogue, and Khnopff was one of several XX painters who responded to it. An 1885 drawing based on the novel showed a female nude, representing Leonora d’Este, in the company of a sphinx. This caused a commotion, because Khnopff transposed the face of the soprano Rose Caron—then preparing to sing in Meistersinger at La Monnaie—onto the naked figure. When Caron protested, Khnopff destroyed the work, although he later made another on the same theme. The artist went on to illustrate several of Péladan’s novels; in the frontispiece of Istar, vegetation is entwined around the crotch of a Venus whose hands appear to be bound above her head.

Khnopff first visited Bayreuth in 1888, the same season that gave Péladan his Eureka moment. He later assisted in the design of opera productions at La Monnaie, including its 1914 production of Parsifal. The young Austrian composer and pianist Alma Schindler, later to find fame as Alma Mahler-Werfel, met Khnopff in Vienna in 1900 and wrote in her diary that the painter “knows and loves every note of Tristan.” After Schindler played the “Prelude and Liebestod” at the piano, Khnopff picked up the vocal score of the opera and pointed to his favorite passages. “He dug his fingernails forcefully into the vocal score and shouted like a man possessed,” Schindler wrote. “Suddenly he said: ‘I must stop, otherwise I’ll get depressed.’”

The chief Wagnerian work in Khnopff’s catalogue is a 1905 drawing titled Isolde, in which the Irish princess tilts her head back and looks out with vacant, lustrous eyes. Alma Schindler’s diary affords a clue to its meaning. The passage in Tristan that Khnopff raved about occurs just after the lovers have drunk the potion. As it takes hold, in a recapitulation of the prelude, Isolde utters the word “Tristan,” over a descending minor-seventh interval. “Khnopff wants to make a free translation of these two notes into color,” Schindler writes. “Of Tristan only an arm—of her perhaps just the face—but all expression concentrated in that face—all the torment, pride, love, hate, every nerve-fibre a-tremble.” Isolde might realize that idea, except that the torment and fury are absent. The heroine is oddly serene, her arched eyebrows and faint smile conveying the hauteur of a woman who knows how men will act. There is something startlingly modern about her: Isolde surveying an urban salon.

If Khnopff partook of Wagnerian esoterica with aristocratic detachment, his younger contemporary Jean Delville, a brash spirit from a poor background, plunged into the thick of the occult, executing hallucinatory visions with almost neoclassical clarity. In 1896, Delville inaugurated the Salons d’Art idéaliste, which he modeled on Péladan’s Rosicrucian salons and on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The first exhibition featured his own Treasures of Satan, in which a muscular Lucifer equipped with a massive head of red hair and elongated tentacles hovers over a writhing mass of nude male and female bodies, their faces more ecstatic than agonized. While Delville, like Péladan, warned of the dangers of uninhibited lust, his version of Hell hints at the Venusian pleasures savored by Baudelaire.

Delville not only idolized the Meister but enlisted him in the battle against naturalism. “The destiny of the Wagnerian work,” he wrote, “will be to annihilate once and for all the naturalist muck where Zola has sat for nearly a half-century.” Like Péladan, Delville felt that realist art foreclosed the possibility of spiritual growth and locked the viewer in the industrial present. Delville’s 1887 drawing Tristan et Yseult is more mystical than erotic—an “animastic union of male and female,” according to the art historian Brendan Cole. Tristan lies on his back, his body in shadow. Isolde is draped over him, one hand holding aloft an empty cup. The bodies together form an upward-arching, triangular mass. Light streams from behind the chalice. This tableau captures the drinking of the potion in Act I, though it also prefigures the opera’s ending: Tristan has a lifeless look, Isolde seems transported. The luminous cup could be mistaken for the Grail.

Odilon Redon, Brünnhilde, 1885

It fell to Odilon Redon to summon on canvas the sublime menace of Parsifal—Delville having fallen short with a kitschy picture of a fleshy youth in curly blond locks. Redon belonged to the Paris vanguard, but he found early recognition among les XX in Brussels. Confronted with the serene severed heads of Redon’s lithographic series In the Dream, the Belgian critic Jules Destrée, later a leading socialist politician, made reference to certain phrases in Wagner that “leave you shivering and troubled for a long time.” In a similar vein, Redon’s bouquets, with their seductive explosions of color against vacant backgrounds, reminded the French decadent author Jean Lorrain of the Flower Maidens in Parsifal, blooming in oblivion.