Полная версия

Полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

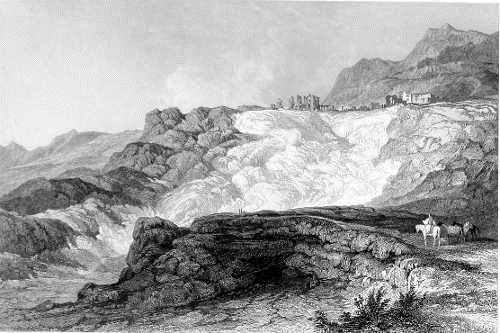

The present state of this “light of Asia,” this “emporium of the world,” forms a sad and striking contrast to its former splendour. The traveller lands on a dismal swamp at the mouth of a river, choked up with sand. Beside this is an extensive jungle of low bushes, the retreat of wolves and jackals, and all the wild animals whose solitary and predatory habits lead them to those haunts, which had once been, but are no longer, the habitations of men. From thence he advances up an extensive and fertile plain, through which the Caÿster winds, exhibiting all the capabilities of culture and abundance, but now a rank marsh, scattered over with muddy pools, the retreat of flocks of aquatic fowls, among which are sometimes seen flights of swans, indicating the permanent character of nature still remaining unchanged, though the habits of man are altered. At some miles from the sea are marble columns, supposed to have formed part of the quay when the river was navigable, and Ephesus the great mart of Asia. Beyond, the plain is skirted by a rising ground, on which appears a succession of ruins for several miles, including a stadium in a more perfect state than the rest; but by far the most interesting are the remains of the temple and the amphitheatre.

On the side of the hill, and partly excavated from it, is a section of a great amphitheatre: the seats have been destroyed or removed, but part of the marble front, many bas-reliefs, and sculptured fragments, attest its primitive splendour. This magnificent area for representing the spectacles of the ancients, gives a high idea of the wealth and population of the city to which it belonged, and the number of spectators it was necessary to accommodate. Immediately below are the supposed ruins of the Artemision, or Temple of Diana, of which Ctesiphon was the chief architect; it was one of the seven wonders of the world: it measured 425 feet in length, 200 in breadth; was adorned with 127 columns, each the gift of a king; occupied 220 years in building; and was eight times reduced to ruins. Its foundations were laid in a swamp, as Pliny says, to guard against the effects of an earthquake. To absorb the damp, wool and charcoal were interspersed, and the arches form a subterranean labyrinth, in which the waters now stagnate. The walls are formed of immense blocks of marble, the faces of which are perforated with cavities; into these were sunk the shanks of the brass and silver plates with which the temple was faced, but they have been long since abstracted. In front are the remains of vast porphyry pillars, which probably formed the portico of the temple. When Constantine the Great issued his decree against heathen worship, this the principal of its temples was finally destroyed, and some of its pillars removed to Constantinople, to adorn the Christian church of the “holy and eternal freedom of God.”—So celebrated was this magnificent pile, that Herostratus, a philosopher, conceived the extraordinary idea of rendering himself immortal by destroying it. He set it on fire on the night Alexander the Great was born, when, as the mythologists say, the goddess to whom it belonged was so engaged in one of her functions at this important birth, that she neglected the care of her temple, and the splendid fabric was burnt to the ground. To defeat the hopes of this incendiary, a decree was issued, rendering it penal to pronounce his name, but this only contributed to preserve it the more.

The vicinity of this ruin to the amphitheatre is an additional and deeply interesting reason for supposing it to be what remains of the ancient temple of Diana. Here was the place where St. Paul excited the disturbance among the silver and brass smiths who worked for the temple; and opposite was the great public resort, where the people were assembling for the exhibition of spectacles, into which they rushed, carrying with them Gaius and Aristarchus, Paul’s companions. Here they had a full view of the magnificent front of the temple “which all Asia worshipped,” and in their enthusiasm they cried out, “Great is Diana of the Ephesians!”

Passing these ruins, the traveller arrives at Aiasaluk, situated on a hill near the upper extremity of the valley. Beside it is the ancient aqueduct which conveyed water to the great city; and near it a church, supposed to be that of St. John, rebuilt by the emperor Justinian, but now converted into a Turkish mosque. All that remains of the habitations of the living is now contained in this Turkish village, whose name still reminds him of its former Christian population. Aiasaluk is a corruption of Ayas Theologos,11 the name by which the Greeks denominate St. John, to whom the neighbouring church was dedicated.

Such is the brief account of the great and interesting city of Ephesus! Its “candlestick has been removed,” as the prophet predicted. All that remains of the Gentile population are, one hundred Turks, enclosed within narrow limits on the summit of a hill; and its numerous Christian congregation is reduced to two individuals, one a Greek gardener, and the other the keeper of a coffee-house,—and these are the representatives of the first great church of the Apocalypse!

The Illustration represents these objects. On the right, in front, are the remains of the theatre, ascending the side of the hill; and before it, extensive ruins are scattered over the surface. Other fragments of edifices are strewed about, and beyond is the humid plain of the Caÿster. In the back ground are the hills which terminate the plain; and under them, on a lower eminence, the town of Aiasaluk, having below all that remains of the church of St. John, and the aqueduct, built by Herodes Atticus from the ruins of the great city.

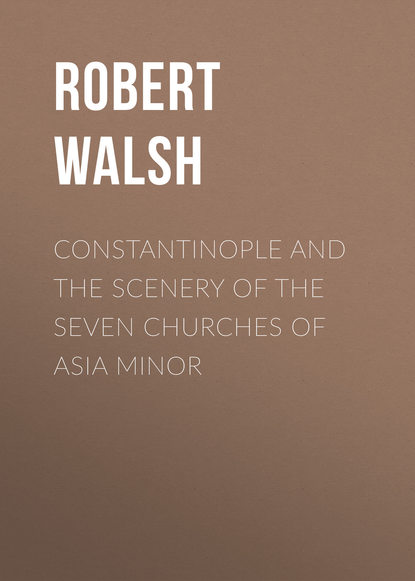

GREEK PRIEST’S HOUSE NEAR YENI KUEY.

ON THE BOSPHORUS

T. Allom. J. Sands.

The various nations that compose the population of Turkey are all distinguished in the metropolis by peculiarities which are not left to their option, but are strictly prescribed to them, that there may be no amalgamation, and the Osmanli may be marked everywhere by separate and distinct characters from their Rayas. Not only the manner of their turban and the colour of their slippers distinguish them from their masters, but the hue of their houses; and while the Turk indulges in every gay and gaudy tint, the mansions of the Jew, Greek, and Armenian are confined to dark and leaden colours, and are at once known by their dull and dismal aspect This is particularly distinguished in sailing along the Bosphorus; and so rigid are the Turks in exacting this distinction, that those who violate it are punished with death. During the progress of the Greek revolution, it set a fatal mark on the devoted inhabitants. The troops, in passing up and down the strait, selected these houses as targets, at which to direct their tophees. Wherever a person appeared at an open window, a volley was discharged at him in very wantonness, till the house was riddled with shot. Nothing could be more dismal than the appearance they presented−their dark and dingy fronts torn and ragged, and the inhabitants frequently hanging out of the windows or against the tattered walls. The rage at one time was particularly directed against the priests. After the execution of their venerable patriarch, all sense of sanctity, which the Turks are willing to allow to the sacred character, whatever be the profession, was converted into hatred and insult. The bishop of Derkon was hung against his own church at Therapia; his clergy were executed whenever they were taken, like common felons, on the shores of the Bosphorus; and the beauty of this fair region was deformed by the most appalling sights. The waters, too, bore frightful testimony of these enormities. The bodies thrown into the current were sometimes carried by the eddies into the little bays and harbours, where they remained putrifying in the still water, tainting the air, and exhibiting to the terrified survivors the decaying remains of their pastors, still wrapped in the vestments in which they died.

Happily this dismal period is passed away, and the constitutional gaiety of the Greeks now evinces its usual hilarity, and their music and dancing again enlivens the shores and villages of the Bosphorus. Their social dispositions, evinced in the structure of their houses, is strongly contrasted with those of the Turks. While the windows of the latter are shut up by impenetrable lattice-work, which is always kept jealously closed, and a human being is never seen in the solitary house, those of the former are distinguished by open casements, at which is generally observed some gay groups of laughing female faces, holding a cheerful and unrestrained communication with any passenger. Nor are the houses of their ecclesiastics prohibited from this social enjoyment. The Greek secular priests are allowed to marry: their religion does not inhibit gaiety, though it prescribes many fasts: they have often a numerous family, and the “priest’s house” has nothing of that ascetic and austere observance that marks the celibacy of the Latin church.

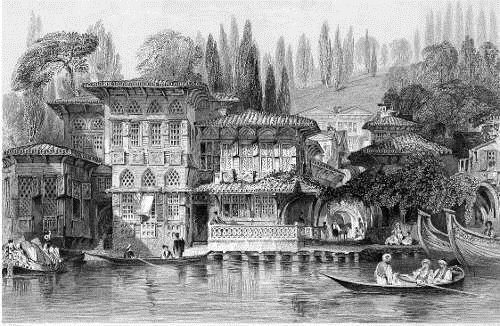

THE ACROPOLIS AT SARDIS.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. W. G. Watkins.

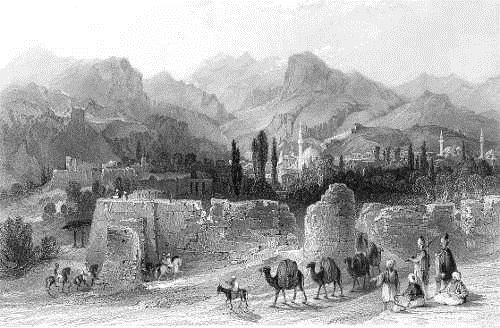

1. Palace of Crœsus, 2. Church Of Panayia, 3. Theatre, 4. Acropolis, 5. The Pactolus, 6. Mount Tmolus.

Sardis, one of the seven churches of the Apocalypse, was anciently the capital of the rich kingdom of Lydia. Here was the court of the splendid Crœsus, the contemporary of Cyrus the Great, to which were invited men distinguished by worth and learning. Here it was that Æsop composed those apologues, which at this day form the rudiments of our education; and here Solon gave that instructive lesson to the monarch on his throne, that riches and prosperity are no protection against the instability of fortune−a truth which the unhappy prince had soon reason bitterly to remember. This city, like others, underwent many vicissitudes. It fell into the hands of Cyrus and the Persians, five hundred and fifty years before the Christian era. It was burnt by the Athenians half a century afterwards; was the occasion of drawing down the resentment of the “Great King” led the Persians to invade Europe; and was the cause of all the celebrated events that followed. It was totally destroyed by an earthquake in the reign of Tiberius, and about the time of the crucifixion of our Lord. Immediately after, the renovated city became distinguished among the seven Christian lights of the world. Sardis was one of those which the prophet, in the Apocalypse, reproves for declension from the Christian faith, and who thus exhorts them: “Be watchful, and strengthen the things which remain, that are ready to die; for I have not found thy works perfect before God:” They despised the admonition; and when Julian attempted to restore paganism, he re-erected in this town all the pagan altars that had been prostrated; and when the Mohammedans invaded Asia Minor, Sardis, like the rest, fell into the power of the inveterate enemies of Christianity.

Sardis, now called Sart by the Turks, has not any collection of human habitations. The only temporary occupants are the hordes of marauding Turcomans, who, with their camels and their flocks, sometimes pitch their tents on the plains, and, when the herbage is exhausted, pass to other places. Ruins scattered over an extensive surface, intimate the existence of a former city, whose name would not be recognized and ascertained, but for the permanent characters of nature which surround it, and still remain unchanged. As Diana was the great deity, and chief object of adoration to the Ephesians, so Cybele was to the Lydians, among whom she was said to be born. Her great temple stood at Sardis. On the plain is still seen the remnant of a noble edifice of which the five columns still standing supported a vast mass of marble, exciting the wonder of the ancients by what power it could be raised so high. It now lies a prostrate fragment, serving only as an indication of the structure to which it belonged. The remains of the Gerusia, or House of Crœsus, are considerable, and consist of brick-work remarkable for its durability. But the objects of greatest interest to the Christian visiter are the ruins of two Churches, those of the Panayia and St. John. Among “the Seven Churches,” these are perhaps the only actual edifices of early Christian worship, that can be distinguished at the present day.

At the extremity of the plain is the hill of the Acropolis, at this day representing, by its shape and position, what the ancient site is described to be. Its front is a triangular inclined plane, not difficult to approach; its rear was an abrupt precipice, supposed to be inaccessible. The view from the summit is commanding, and includes the vast plain of the Hermus, the tomb of Halyattes, and the Gygean lake. When Antiochus besieged the city, he observed that vultures and birds of prey were gathered about offals thrown from the fortress above, and he sagaciously inferred that the wall of this place was low, and negligently watched. It is added, that a Persian soldier, allured by a high reward, attempted to climb the dangerous precipice; and having done so, he descended, and pointed out the way to his companions, who followed him, and entered the citadel. The front aspect of the Acropolis, which is accurately represented in our Illustration, exactly corresponds with this detail. Behind the Acropolis rise the ridges of mount Tmolus, covered with snow, and once celebrated for vines and saffron, odoriferous shrubs, and the longevity of its inhabitants. These properties of nature it retains to this day, and travellers speak of its balmy air, and the rich fragrance that is wafted from its aromatic herbs. In it the celebrated Pactolus took its rise, and, pouring down its auriferous streams, enriched the capital with such abundance of gold, that mythologists accounted for it in their fanciful manner. The mountain has parted with all its auriferous particles, and the golden reservoir is exhausted, but the sands are still of a ruddy hue, and justify the name of the “Golden Pactolus.” The splendid remains of Sardis are calculated to recall early impressions, and excite the most solemn reflections. Once the capital of the richest kingdom on earth, and her name associated with mighty events, she affords now no permanent habitation to any human being, while her whole Christian population is comprised in two servants of a Mohammedan miller in the vicinity.

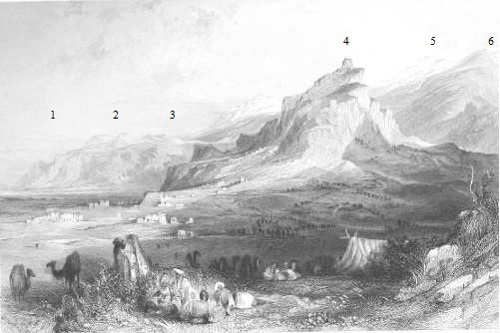

THE PALACE OF SAÏD PASHA.

ON ONE OF THE RAPIDS OF THE BOSPHORUS

T. Allom. J. W. Lowry.

The first objects that present themselves on ascending the Bosphorus, are the palaces of the several female members of the imperial family, hanging, as it were, over the water. They display long fronts, with coarse balconies of wood, having little of architectural beauty to recommend them. Each balcony is supported by sloping beams of timber, the upper projecting beyond the lower, so as to impend over the water, leaving a narrow quay as the public street beneath. The windows are closed up with more than Turkish jealousy. The lattices are dense and impervious to all view, leaving only one minute aperture, to which the inmate of the harem applies her eye when she wishes to contemplate the busy and living picture continually before her.

The first of these palaces is that of the Asmé Sultana, the sister of the present sultan. It is distinguished by its brazen doors, and by the sounds of music continually issuing from it, particularly at night; when concerts attract multitudes of boats, and caïques of all sizes, filled with company of every grade, crowd the Bosphorus before it. Next this is the palace of the sultan’s daughter, the princess Sahilé, and beside it the humbler edifice of her spouse−the difference of rank still scrupulously observed, that the son-in-law may not forget that he is married to the daughter of the sultan. Immediately beyond is the palace of Saïd Pasha, lately united to the princess Mirameh, the youngest marriageable daughter of the imperial family. The pasha has availed himself of the privilege denied to the rayah, by painting his house of “a rosy hue,” alluding, it is said, that emblematic colour, to the happiness of his nuptial state.

Immediately below the palace is one of the rapids called by the Greeks Megalé roë, and by the Turks, Buyuk akindisi, over which the stream tumbles sometimes with the velocity and turbulence of a cataract, and is supposed to be one of the evidences of that awful convulsion which tore open the strait, and sent the waters of the upper ocean down to the lower regions in an eternal current. As no vessel can ascend here by force of oars, it is necessary to tow them. The shore is seen lined with men holding coils of cord: when a vessel arrives, the efforts of the crew are suspended; the coil is cast to the ship, and fastened to the prow; it is then passed over the shoulders of a long line of men, and by main force, and most laborious exertions, the largest and most ponderous ships of the Black sea are thus dragged up the descent, with a bodily strength and perseverance which a Turkish hammal alone can exert. When the lighter caïque arrives, it ascends with little labour. The passenger then wraps a few paras in a morsel of paper, throws them ashore to the robust assistants, the tow is thrown off, and the light caïque, now arrived at the summit, shoots on its way. The introduction of steam-boats was opposed, as depriving so many persons of a means of support, but they are now used for larger vessels, and partly abridge this painful toil.

THE RUINS OF HIERAPOLIS.—NOW CALLED PAMBOUK KALESI.

ON THE WAY FROM LAODICEA.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. E. Benjamin.

Hierapolis, or “the Sacred City,” stands on the confines of ancient Caria and Lydia, in Asia Minor, and a few miles from Laodicea. It is now called Pambouk kalesi, the first part of the name signifies “cotton,” from a very singular phenomenon. On approaching the place, the traveller sees before him the sloping face of a hill, of a pure white, and apparently fleecy texture, swelling into little eminences, and resembling a mass of wool laid upon the surface, and as if slightly agitated by the wind. The soil abounds with hot springs, and this singular appearance is a pure white concrete substance, generated by the water flowing over the steep, and leaving behind a chalky deposit. On being tested with acids, it is found to ferment; and like the dropping-well at Knaresborough, and from the same cause, leaving behind it an incrustated surface of carbonate of lime wherever it flows. The abundance of this concrete deposit was so great formerly, that it performed the function of Amphion’s lyre, and raised spontaneous walls. The water was conducted round edifices and enclosures, and the channels then became long fences of a single stone. When the rill first drips over any surface, it leaves behind it a lurid appearance, resembling wet salt, or half-dissolved snow. Several of the vineyards and gardens are now fenced with this substance.

Over the summit of this chalky cliff appear the remains of Hierapolis. These consist of the ruins of a stadium, and amphitheatre, which no ancient town, yet discovered, has been without; they were the most indispensable, and the most permanently built. The meanest as well as the most insignificant cities seem to have thought them necessary to their well-being. Mixed with these are numerous sarcophagi, with and without covers; the whole occupying a space of one mile in length; and among the inscriptions found are some celebrating this city for its hot springs, declaring it to be revered over Asia for its salubrious rills. It was, therefore, dedicated to Apollo, who, with Æsculapius and Hygeia, appear on the medals which remain. They had another property, that of assisting the tincture extracted from vegetable dyes, and imparting to wool its richest purple.

Besides its hot springs, Hierapolis was distinguished by a very remarkable and deleterious exhalation, called very properly, plutonium, as appertaining to the key of the infernal regions. This was a small excavation in an adjoining mountain, having an area before it of four or five hundred yards in circumference. This space was always filled with a dense vapour, so that the bottom could not be discerned. Like the modern Grotto del Cane, this vapour was mortal to those who breathed it; bulls and other animals were driven into the enclosure, and immediately fell down suffocated; and birds, as at Averno, dropped senseless when attempting to fly across it. The priests of Cybele, availing themselves of this mephitic cavern, pretended to work a miracle. They alone were able to walk through the exhalation unhurt. The imposture is easily detected; the vapour is carbonic acid gas, like that of the grotto in Italy; it is a dense and heavy fluid, which does not rise high above the ground. Animals, whose heads are immersed in it, are immediately suffocated; but those who walk erect, above the surface, pass through it with impunity.

PHILADELPHIA.

CALLED BY TURKS ALLAH SHER, THE CITY OF GOD

T. Allom. W. Floyd.

Of all the churches of the Apocalypse, Philadelphia retains more of its former Christian character than any other. Ephesus and Sardis are not but Philadelphia is; and the profession of Christianity is not only cherished there by a large population, but it is presided over by a Christian bishop; and while the cooing of turtle-doves in every tree, the mansion of the filial stork in every roof, and sundry other objects of nature, of soothing sound and placid aspect, reminds the traveller of its Christian name, Philadelphia, or “brotherly love,” the Turks, as if to mark its former sanctity, now call it Allah Sher, or the “City of God.” The inhabitants, too, are of a most urbane character, and have obtained for themselves, in the barbarism that surrounds them, the eulogy of being a “kind and civil people.”

The city was originally built, like many others that long adorned Asia Minor, by descendants of the enterprising soldiers that followed Alexander the Great in his Persian expedition; who, after carrying war and its destructive train into the countries of the East, compensated their ravages by building cities in the place of those they had destroyed, and leaving behind them the arts and language of Greece. Attalus Philadelphus selected a site at the foot of Mount Tmolus, and called it Philadelphus, after himself. When Christianity expanded, the inhabitants early received the Gospel, and it became one of the churches distinguished by the Evangelist among the seven. He eulogizes it as that which “kept the word of God, and denied not his name.” An impression remained on the minds of the people, derived perhaps from their interpretation of the Apocalypse, that their city never had and never would be taken. When, therefore, the Moslems inflicted ruin and desolation on other Christian communities, the inhabitants of Philadelphia despised them. They had heard that they had “laid waste defenced cities into ruinous heaps,” yet they read that “by the way they came, they should return,” and “not come into this city.” They therefore made a vigorous resistance, and though remote from the sea, and bereft of all maritime aid, they, for near a century, and long after other Christian cities had been destroyed, repelled all the attempts of the Osmanli. At length, exhausted by famine, they could make no further resistance, and fell under the superior power of Ilderim, the Turkish Thunderbolt.

The town stands upon a hill, and, like all Greek cities, ascends to an acropolis. Around the base expands a singularly rich country, even now in a high state of cultivation, divided into gardens and vineyards, and beyond them one of those verdant and fertile plains which distinguish Asia Minor. There are few remains of antiquity which mark the era when Grecian art flourished. Such walls and masses of masonry as now stand, belong to the time of the Lower Empire. Among the barbarous remnants of those times is a wall of human bones, cemented together, near the town, and said to be evidence of the massacre perpetrated by Bajazet, who formed the structure as a monument of the terrible effects of resisting his wrath. It is a companion for the pyramid of human heads which his rival Tamerlane erected on similar occasions.