Полная версия

Полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

These people were once the most fierce and untractable savages, and the scourge of the Greek empire. They were, and are still called Bulgarians, or Volgarians, from the river Volga, from whose shores they originally migrated to this place; and for centuries they threatened the very existence of the enfeebled state. In the reign of Justinian, they approached the city of Constantinople with fire and sword, but were repulsed by the great Belisarius. After various defeats, they were converted to Christianity, and their subdued and broken spirits, aided by the mild influence of the new religion, produced such an effect, that, instead of the once rude and ferocious mountaineers reported by historians, they are now, though the same race and in the same locality, distinguished for industry, for mildness of disposition among themselves, and kindness and hospitality to strangers. They have extended their population to the plains below, on each side: on the north to the Danube, and on the south nearly to the Propontis; and their manners form a strong contrast to those of the rude and inhospitable Turks, with whom they here mingle.

When a traveller enters a cottage, he is received with smiles and cheerfulness, as if he were one of the family returned home after an absence. The females treat him with that unsuspecting confidence which they would show to a brother, and with a good-will which those who have experienced their hospitality will never forget. The young women are particularly distinguished by their dress. They wear in some parts a blue, and in other a white cloth gown, wide and open at the sleeve and bosom, displaying a snow-white chemise of cotton or linen, tastefully embroidered. This gown is sometimes cinctured with a band and buckle of dressed leather, or bound by a red girdle, to which the cloth skirts are tucked up when dancing, or in other active motions. But that which most distinguishes them is the ornament of the head: it is fancifully dressed, and braided with a great variety of coins of different metals, sometimes so densely strung together, that they form a thick metallic cord of considerable weight, and presenting the edges of the coins. These are esteemed the retecules in which a young lady preserves her marriage portion; and when the pendent purse is broken up, these perforated coins, first used as ornaments, are seen in constant circulation. When a traveller enters a cottage, and demands the rites of hospitality, it is swept and garnished for him, and the carpets laid; and, while he reclines upon it, the belle of the village enters with a white handkerchief in her hand, leading a train of her companions: they form a dance of pleasing movement, and a chorus of sweet voices expressive of welcome. When it is concluded, the fair conductress approaches, and casts her handkerchief into his bosom; this implies a request for a few paras, which is never denied, and “the village train” depart with cheerfulness and modesty.

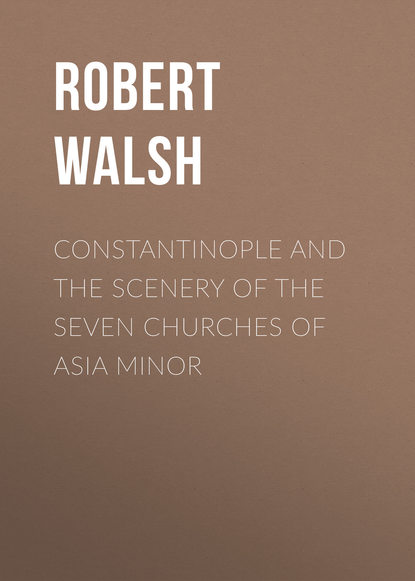

PASS IN THE BALKAN MOUNTAINS.

BY HAIDHOS

C. Bentley. T. Jeavons.

In this great and apparently impenetrable chain, five passes have been discovered, each at a considerable distance, by Haidhos, Karabat, Jamboli or Selimno, Kersaulik, and Tâtar-bazaar. Of these, the passes by Haidhos and Tâtar-bazaar are the most picturesque—the one at the east, and the other at the western extremity of the mountains.

From Haidhos the traveller begins to ascend, and, after surmounting the Low Balkans, and passing the lovely valleys between them, finds himself in a deep sequestered vale, surrounded on all sides by mountains. Directly before him is the vast wall of rock, extending interminably both ways, and presenting a perpendicular form ascending to the skies. When close under it, the flank seems suddenly, as it were, torn open by some rupture, presenting a dark chasm, which before was not seen. This he enters beside a rivulet, and for some time descends with it towards the very bowels of the mountain, involved in dim twilight below, and seeing, at an immeasurable distance above, a scarcely describable stripe of blue sky. Ascending, and winding his way, up one side of the chasm, he at length emerges on the summit, and stands on the ridge of the High Balkans, enjoying a prospect, of unparalleled extent and magnificence, of the less elevated hills and plains below. From hence the road proceeds across a kind of table-land, generally enveloped in mist and entangled in morasses, crossed by various ravines and tottering planks, so loosely set as to rise at one end as the traveller presses the other, or by decayed wooden bridges, which frequently break down, and precipitate horse and rider into the abyss below. Reaching the opposite or northern face of the ridge, the way descends to Lopenitza, a Balkan village, after a transit of twenty-seven miles, across the High Balkans, and proceeds to the Danube by Shumla.

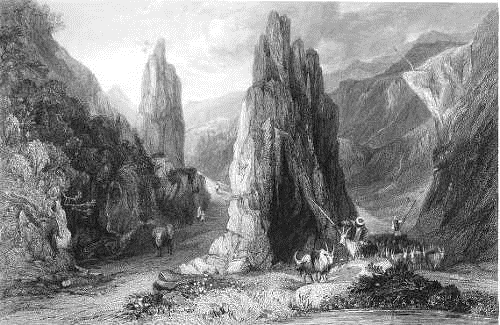

ROUTE THROUGH THE BALKAN MOUNTAINS, BY TÂTAR-BAZAAR.

ON THE FRONTIERS OF BULGARIA & ROUMELIA

Drawn from Nature by F. Hervé. Esq. Engraved by J. Tingle.

The western pass, by Tâtar-bazaar, presented in the Illustration, is not approached by a chasm so singular and wild as that by Haidhos, but the passage on the summit is of a much more grand and romantic character. The distinct mountains rise into immense cones of splintered schist or granite, indented into clefts and fissures. Sometimes masses of rock rise perpendicularly beside the traveller, between which the road passes, with sharp-pointed tops, of a pyramidal form, and outline so regular, as to make it doubtful whether they are not artificial constructions. The road runs between them, and they stand like “mountain sentinels” placed to guard the pass. The delusion is increased when he arrives in this wild and lofty region at the remains of a great arch of Roman brick, which apparently was one of those pylæ, or mountain-gates, raised, to guard against the incursions of the barbarous hordes from Dalmatia, Dacia, and other places beyond the mountains, who for centuries continued to press and harass the declining Roman empire. Such is the use to which it is at present applied. Here is stationed a Dervenni, or guard of Albanian soldiers, which form part of the cordon of posts, planted in various parts of the ramparts of the chain, when the Russians prepared to ascend and pass it. The Turks, in several parts of their vast empire, both in Europe and Asia, select those points for defence which the Greeks and Romans also appear, by their remains, to have chosen, but they never think of repairing the old gate, or strengthening the pass by new fortifications.

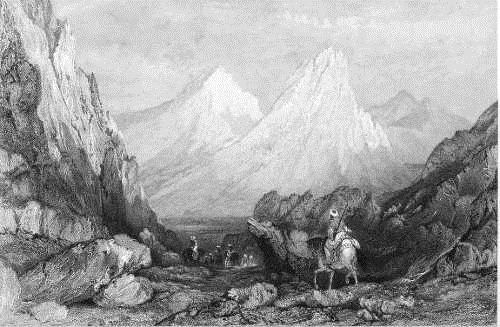

THE BABYSES, OR, SWEET WATERS OF EUROPE

T. Allom. P. Lightfoot.

Only two rivers flow within many leagues of the great city of Constantinople; they rise at a short distance between it and the Black sea, and wind their way along a valley at the head of the Golden Horn. One of them was formerly called the Cydaris, and now the Bey Low; the other the Babyses, now changed to the Kyatkana Low, or “Water of the Paper Manufactory.” Where they fall into the harbour, the soil is alluvial and marshy, and the quantity of slime collected there induced the ancients to designate it “Marcidem Mare,” “the Putrid Sea.” The French, however, called it, les Eaux Doux, because the water was not salt; and the English now denominate it the “Sweet Waters.”

Notwithstanding that the waters are impure, and the high grounds around sterile and denuded, the place possesses many attractions. Higher up the stream, the valley improves, and circumstances have given the locality much celebrity. The paper factory having fallen into ruins, Sultan Selim built a kiosk in its place, in imitation of the palace of Versailles. A mound has been thrown across the river, and the stream detained, so as to form a large and tranquil sheet of water. On its banks stands the kiosk, one side of which is supported by pillars rising out of the water. It was once a favourite residence of Mahmoud II., but a slave, to whom he was greatly attached, died here in the prime of life; and her master having erected a tomb to her memory on the bank, abandoned the place for many years. Time, however, has worn out the impression, and it is again a favourite retreat. At the head of the valley is the Ocmeidan, or “Place of the Arrow,” the royal archery-ground; and marble pillars, erected at different distances, attest the Sultan’s skill, and the almost incredible distance to which he can send a shaft. On these occasions, he is attended by his officers, and sometimes the females of his family, in arrhubas: the valley is then shut up with guards, and no stranger permitted to intrude: at other times, it is open to all classes, who come here to rusticate, particularly Greeks, on Sundays and festivals.

There is one period, however, in which it is the thronged resort of every person seeking amusement; and the Golden Horn is covered with caïques from all parts of Pera and Constantinople. This occurs on St. George’s day in the month of May, when the splendid stud of the sultan is brought out from the stables of the seraglio, for the first time in the season, to graze on the rich herbage of this place. The horses are in the care of Bulgarians, and crowds of peasants accompany their countrymen. They come down from the Balkan mountains at this season of the year, to dress the vineyards about the city; and groups of them, with their honest, good-natured faces, are seen everywhere dancing through the streets. Their dress is a jacket of brown cloth, caps of brown sheep-skin with the wool on, and sandals of raw hide, drawn under the sole, and bound over the instep. But what particularly distinguishes them is an enormous bagpipe. The minstrel draws after him a crowd of his countrymen, capering through the streets of Pera and Constantinople, on their way to the Sweet Waters, to amuse the company assembled there. The banks at this season are covered with a rich verdure, and enamelled with a profusion of flowers of all hues: the very humidity of the soil confers a luxuriance on the sward which is nowhere else to be seen. The soil round the city is a poor and sterile gravel, and for nine months in the year presents a parched and arid surface of irksome brown; it is only in the cool, humid valleys, that a blade of verdure is to be seen. This spot, therefore, is much frequented by the Franks; and there is no stranger on a visit to the capital, who is not invited to see the Sweet Waters. The Illustration represents one of these festive meetings. On the right of the foreground is a group of Greek girls, dancing through the graceful mazes of the romaika, their unveiled faces and necks, and their neatly sandalled feet, forming a striking contrast to the yasmaks and slippered-boots of other Oriental females of the capital. In the background are companies engaged in various festivities, and embosomed in the trees; behind is seen the sultan’s kiosk, with a never-failing minaret peeping through the foliage.

INTERIOR OF A TURKISH CAFFINET.

CONSTANTINOPLE

T. Allom. W. H. Capone.

Many circumstances strike a stranger on entering Constantinople, and many objects different from those to which he has been accustomed in European Christian cities. Here are no straight spacious avenues, thronged with foot-passengers on the wide flags, and with carriages on the level centre; no names to the streets, to direct his way; no advertisements on walls; no women behind counters; no public places, for walking or amusement; no monuments displaying taste, or recording great men or actions; no libraries or news-rooms; no club-houses; no theatres, or public exhibitions; no hackney-coaches, cabs, omnibuses, sedan-chairs, or equipages of any kind, either public or private; no clocks on steeples or public buildings, indicating the hour of the day, nor bells announcing festivals or public rejoicings; no lamps to illume the city by night; no shops blazing with the glare of gas; no companies flocking to or from balls; or parties or public assemblies, of any kind, thronging the streets after night-fall, and making them as popular as at noon-day. On the contrary, he gets entangled in crooked, narrow, steep lanes, where the pavement is so imperfect that he is every minute in danger of breaking his leg between the loose angular stones. During the sunlight, the busy throng is nowhere to be seen but in the bazaars, or the avenues leading to them; and every other place seems totally deserted, except by dogs, who howl when he appears, and attack him in whole packs. The only equipage he sees is the sultan’s, going to some mosque on Friday, when the people congregate in the street through which he passes. The only carriages are women’s arrhubas, or kotches, which, generally speaking, cannot climb the steep and narrow streets. When they do appear, they are conveying, closely shut up, the harem of the sultan or some pasha, and then they are accompanied by black eunuchs with drawn sabres. Their approach is announced by the dead silence that suddenly pervades the busy din of a crowded thoroughfare: the moving mass of the people is suddenly arrested, and every man stands closely wrapped up in his beniche, with his arms folded on his breast, and his head cast down and turned away. The unfortunate person who neglects this, is liable to be cut down, and forfeit his life upon the spot for his negligence. At sunset all the shops are shut up, and their owners hurry to their respective residences; and when the evening closes in, the streets are as dark and as silent as the grave. If a Frank, following the usages of his country, remain at the house of a friend beyond the limited hour, he is liable to be arrested by the Coolah guard, unless he be attended by some lights. He often lights himself. He goes into a Baccùe, or huckster’s shop, while it is open, and purchases for a few paras a circular fold of paper. This is a lantern compressed into a flat surface, which may be elongated to the extent of half a yard. He draws it out, places a light outside, attaches it to the end of his long chibouk, and smoking in this way, with the light thrust out before him, is protected, on returning home through the streets, at any hour of the night.

The only places of public resort that seem in any way to remind him of the social habits of a European city, are the taverns and coffee-houses. Even these are distinguished by customs peculiarly Oriental. The tavern is an open shop, where cooks are employed in preparing different kinds of refreshment over small counters filled with red-hot charcoal. Having passed these, he is shown into a dark room behind, or above, through a narrow staircase. Here he sits down on a tattered straw mat, and a joint stool is placed before him, on which is laid a clumsy metal tray; presently an attendant comes with two dishes, of coarse brown earthenware, one containing a mess of thick, heavy, greasy pancake, made of flour, and the other a skewer of kabobs. Kabobs are small pieces of mutton, about the size of penny pieces, which they much resemble in shape and colour, roasted on an iron needle, which is served up with them. There is no napkin, no knife, fork, or spoon, no wine, beer, or spirits. The entertainment concludes in about ten minutes with a glass of plain water, or, in extreme cases, a cup of sherbet.

The caffinet, or coffee-house, is something more splendid, and the Turk expends all his notions of finery and elegance on this, his favourite place of indulgence. The edifice is generally decorated in a very gorgeous manner, supported on pillars, and open in front. It is surrounded on the inside by a raised platform, covered with mats or cushions, on which the Turks sit cross-legged. On one side are musicians, generally Greeks, with mandolins and tambourines, accompanying singers, whose melody consists in vociferation; and the loud and obstreperous concert forms a strong contrast to the stillness and taciturnity of Turkish meetings. On the opposite side are men, generally of a respectable class, some of whom are found here every day, and all day long, dozing under the double influence of coffee and tobacco. The coffee is served in very small cups, not larger than egg-cups, grounds and all, without cream or sugar, and so black, thick, and bitter, that it has been aptly compared to “stewed soot.” Besides the ordinary chibouk for tobacco, there is another implement, called narghillai, used for smoking in a caffinet, of a more elaborate construction. It consists of a glass vase, filled with water, and often scented with distilled rose or other flowers. This is surmounted with a silver or brazen head, from which issues a long flexible tube; a pipe-bowl is placed on the top, and so constructed that the smoke is drawn, and comes bubbling up through the water, cool and fragrant to the mouth. A peculiar kind of tobacco, grown at Shiraz in Persia, and resembling small pieces of cut leather, is used with this instrument. The pipe is lighted either by a fragment of ignited charcoal, or amadhoo; this last is an inflammable spark prepared from decayed wood, or a particular kind of fungus, and a Turk never goes without a portion of it, with a flint and steel, in his tobacco-bag. In the centre of the room is generally an artificial fountain, bubbling and playing in summer, and round it vases of flowers, with piles of the sweet-scented melons of Cassaba, to keep them cool, and add, by their odour, to the fragrance of the flowers.

A frequent addition to the enjoyments of the caffinet, is the medac, or story-teller. There are several of these public characters at Constantinople, who, at festival seasons, are engaged by the caffinet-ghees to entertain their guests. On these occasions, to accommodate the increased company, stools are placed in semicircles in the streets before the caffinet, and refreshment sent from the house. A small platform is laid on the open window, so that the audience within and without may hear and see. On this the story-teller mounts, and continues his narrative sometimes till midnight. The excellence of some of these men in their department, is surprising, and altogether out of keeping with the dull and phlegmatic character of a Turk. In humour and detail, they are equal to the best European actors; and sustain singly, and without any aid, a whole drama of various characters. Their tact is equally clever. When the attention of their audience is excited to the highest degree at the approach of some interesting catastrophe, the medac suddenly steps down from his platform, and going round with a coffee-cup in his hand, the audience soon fill it with paras, to induce him to resume his place; and then, and not till then, does he mount, and go on with his story. One of these medacs, called Kiz Achmet, or “Achmet the Maid,” was particularly famous. He has been engaged during the Bairam at a salary of eight hundred piastres; and the sultan often sent for him, to entertain the ladies of the harem, though his stories on ordinary occasions were of a very coarse and indelicate character.

THE VILLAGE OF BABEC,

ON THE BOSPHORUS

T. Allom. J. Sands.

In a very deep recess, formed by the expansion of the Bosphorus, immediately above the Buyuk Akendisi, or “Great Rapid,” and between it and the Roumeli Hissar, or Castle of Europe, are the bay and village of Babec. The latter extends along one side of it, having a level quay in front, and generally exhibits a scene of busy population, with its caïques and fishery. Beyond it rise the wooded hills which skirt the shores of the Bosphorus. Here the steep ascent is clothed with a very dense growth of trees, casting their dark shadows on the waters below, which wash the margin of the deep recess of the bay, and give it a peculiarly sequestered and solitary appearance. Here, in the darkest shade, is seen a lonely kiosk, which strikes the traveller passing in a caïque, as having something more than ordinary connected with it. The kiosk is shut in with walls, the entrance entirely closed up, and no human being is ever seen to enter or depart from it. The jealous precaution usually visible about a Turkish house always has a desolate and repulsive aspect; but this kiosk, it has been remarked, has a solitude even more than Turkish, and, without the usual marks of desertion, decay, and dilapidation, it looks as if abandoned by inhabitants, or devoted to some secret or mysterious purpose. It is the retreat of Turkish diplomacy−the appointed spot for secret negociations.

Mystery and deception, the wheels on which it usually moves, are here practically exemplified. The bureaus of the Porte are appointed for the transaction of ordinary business, but on extraordinary occasions it is transferred to this place; and this solitary recess of the Bosphorus is resorted to in order to prevent any possibility of the secret transpiring. When it is necessary to meet a foreign minister, on any affair of importance, he is directed to repair to this place. Hither he comes in his caïque, divested of pomp or parade, and endeavouring to pass without any notice. He climbs the rapid, and creeps along the shore of this sequestered bay, to the mysterious kiosk, and is, with due precaution, admitted. He finds, within, the reis effendi, or minister for foreign affairs, who has approached by land with similar precaution. The doors are closed, and the conference commences. When the affair is arranged, the diplomatists separate, and the kiosk is abandoned, and closed up till another mysterious affair renders another mysterious conference at this place necessary. This attempt at concealment is highly characteristic of the court and the people; but it is altogether defeated. The prying jealousy of the ministers of the European powers resident at Constantinople, is continually on the alert: the chief dragoman of one mission makes a daily report to his ambassador of what every other is doing, or about to do: he visits the bureaus of the Porte, and worms out the most secret intentions; and while the principals are shut up at Babec, as they suppose, unknown to all the world, the tattling dragomans are every where disclosing the subject they are discussing, and the conference at Babec is no more secret than the news of a public coffee-house.

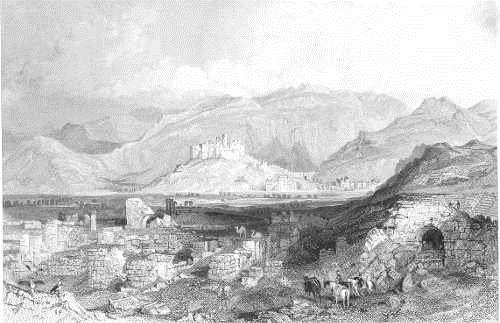

THE RUINS OF EPHESUS.

THE CASTLE OF AIASALUK ON THE DISTANCE.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. W. J. Cook.

This city is not only celebrated in profane history, which ascribes its foundation to the Amazons, but is rendered interesting to mankind, for being commemorated in the Sacred Scriptures by many important recollections. When Christianity began to expand itself in Asia, seven churches were founded, eminently distinguished among the early Christians, as fountains, whence the light of the gospel should flow upon a benighted world. The first and chief of these was the great city of Ephesus. When St. John in his Apocalypse addresses these seven churches, the first he named was that of Ephesus. To the professors of Christianity there, he gives a high character, intimating the reformation which the infant gospel had already effected among the Gentiles. “I know thy works, and thy labour, and thy patience, and how thou canst not bear those that are evil.” To this church, St. Paul addressed his epistle when in bonds at Rome, to guard them against that false doctrine that was even then beginning to taint the purity of the gospel. This city he visited in his travels, and adds the testimony of sacred history to that of profane, to the estimation in which the great heathen temple was held; and from this city he took his final departure at that affecting moment, when they kneeled down, and prayed on the sea-shore, “and wept sore for the words which he spake−that they should see his face no more.” This city once had a bishop, the angel of the church, Timothy, the beloved disciple of St. John; and tradition reports that it was honoured with the last days of both these great men, and of the Mother of our Lord.