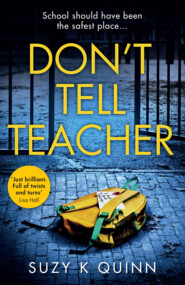

скачать книгу бесплатно

I can barely believe this is happening. A nobody chalet girl like me, being chatted up by this confident, tanned athlete. I guess I should enjoy it while it lasts. When he works out what a nothing I am, he’ll run a mile.

I laugh. ‘Are you always so forward with your wedding plans?’

‘Only with my future wife.’

‘You don’t even know me.’

‘Yes, but I’ve been watching you and your purple puffer jacket for ages, wondering how you don’t freeze to death in those DM boots.’

‘Where have you noticed me?’

‘Drinking black coffee in the café, buying a ginger cookie and giving crumbs to the birds on your way out. Always carrying a pile of books under your arm. Are you a student?’

‘I’m training to be a nurse.’

‘A nurse? Well, Lizzie Nightingale, you’ll have to put your career aside when you have my five children.’

‘Five children?’

‘At least five. And I hope they all look just like you.’

Our eyes meet, and in that second I feel totally, utterly alive.

I’ve never been noticed like this.

It’s electrifying.

And I feel myself hoping, like I’ve never hoped before, that this man feels the same sparks in his chest as I do.

Kate (#ulink_69c8d610-5336-5b92-abdd-53453f35476f)

8 a.m.

I’m eating Kellogg’s All-Bran at my desk, silently chanting my morning mantra: Be grateful, Kate. Be grateful. This is the job you wanted.

Apparently, social workers suffer more nervous breakdowns than any other profession.

I already have stress-related eczema, insomnia and an unhealthy relationship with the office vending machine – specifically the coils holding the KitKats and Mars bars.

Last night I got home at 9 p.m., and this morning I was called in at 7.30 a.m. I have a huge caseload and I’m firefighting. There isn’t time to help anyone. Just prevent disaster.

Be grateful, Kate.

My computer screen displays my caseload: thirty children.

This morning, I’ve had to add one more. A transfer case from Hammersmith and Fulham: Tom Kinnock.

I click update and watch my screen change: thirty-one children.

Then I put my head in my hands, already exhausted by what I won’t manage to do today.

Be grateful, Kate. You have a proper grown-up job. You’re one of the lucky ones.

My husband Col is a qualified occupational therapist, but he’s working at the Odeon cinema. It could be worse. At least he gets free popcorn.

‘Well, you’re bright and shiny, aren’t you?’ Tessa Warwick, my manager, strides into the office, clicking on her Nespresso machine – a personal cappuccino maker she won’t let anyone else use.

I jolt upright and start tapping keys.

‘And what’s that, a new hairdo?’ Tessa is a big, shouty lady with high blood pressure and red cheeks. Her brown hair is wiry and cut into a slightly wonky bob. She wears a lot of polyester.

‘I’ve just tied it back, that’s all,’ I say, pulling my curly black hair tighter in its hairband. ‘I’m not really a new hairdo sort of person.’

I’ve had the same hair since I was eight years old – long and curly, sometimes up, sometimes down. No layers. Just long.

‘I might have known. Yes, you’re very, very sensible, aren’t you?’

This is a dig at me, but I don’t mind because Tessa is absolutely right. I wear plain, functional trouser suits and no makeup. My glasses are from the twenty-pound range at Specsavers. I’ve never signed up for monthly contact lenses – I’d rather put money in my savings account.

‘I’m glad you’re in early anyway,’ Tessa continues. ‘There is a lot to do this week.’

‘I know,’ I say. ‘Leanne Neilson is in hospital again. Gary and I were up until nine on Friday trying to get her boys into bed. I just need time to get going.’

Gary is a family support worker and absolutely should have finished at 5 p.m. So should I, actually. But two out-of-hours team members were off sick and we were swamped.

Tessa inserts a cappuccino tablet into her Nespresso machine. ‘So you were babysitting the three Neilson scallywags?’ She gives a snort of laughter. ‘They’re like child versions of the Gallagher brothers, those boys. All that black hair, fighting all the time. You never know – maybe they’ll be famous musicians. But you shouldn’t have been putting them to bed. You should be in the pub of an evening, like a normal twenty-something.’

It’s a bone of contention between us – the fact I rarely drink alcohol. Also, that I married at twenty years old and go to church twice a week.

‘Jesus drank, didn’t he?’ Tessa continues. ‘I thought it would be okay for you lot.’

‘Us lot?’

‘You young churchy types. You’ll be drinking soon,’ Tessa predicts. ‘Just you wait. You’re new to this, but everyone ends up on the lunchtime wine eventually. Now listen – have you done the home visit for that transfer case yet? From Hammersmith and Fulham, Tom Kinnock? The one with the angry dad.’

‘No. I sent a letter on Friday. She’ll get it today.’

‘Get on to that one as soon as you can, Kate. The transfer was weeks late. There’ll already be some catching up to do. Have they got him a school place?’

‘Yes. At Steelfield School.’

‘I bet the headmaster is furious,’ laughs Tessa. ‘“More social services children thrust upon us … we already have the Neilson boys to deal with.’”

‘I’m not sure a high-achieving school is the right environment for Tom Kinnock,’ I say. ‘Very strict and results obsessed. After what this boy has been through, maybe he needs somewhere more nurturing.’

‘Don’t worry about the school,’ says Tessa. ‘Steelfield is a godsend. They keep the kids in line. No chair throwing or teacher nervous breakdowns. Just worry about getting that case shut down ASAP. The father is a risk factor, but all the dirty work is done.’

‘I’m pretty overwhelmed here, Tessa.’

‘Welcome to social work.’ Tessa gives her Nespresso machine a brief thump with a closed fist.

Lizzie (#ulink_56162e55-cd5e-5352-9d3b-c94bcbd60afd)

A brown envelope, addressed formally to Elizabeth Kinnock. The mottled paper has a muddy shoeprint from where I stepped on it.

I study the postmark. It’s from the county council, i.e. social services. I know these sorts of letters from when we lived with Olly. We’d like to meet to discuss your son …

I should have known social services would want to meet us. Check we’re settling into our new life. But we don’t need any of that official stuff now. Olly is gone.

My fingers want to scrunch the brown paper into a tight ball, then push the letter deep down into the paper recycling, under the organic ready-meal sleeves and junk mail. Stuff away bad memories of an old life, now gone.

But instead I shelve the letter by the bread bin, resolving to open it after a cup of tea. There are other letters to read first.

I sit on the Chesterfield sofa-arm and slide my fingers under paper folds, tearing and pulling free replies to my many job applications. They’re all rejections – I’d guessed as much, given the timing of the letters. If you get the job, they mail you straight away.

I look around the growing chaos that is our new house. There are toys everywhere, children’s books, a blanket and pillow for when Tom dozes on the sofa. Really, it’s hard enough keeping on top of all this, let alone finding a job too.

The house was beautiful when we moved in over the summer – varnished floorboards, cosy living room with a real fireplace, huge, light kitchen and roaming garden full of fruit trees.

But all too quickly it got messy, like my life.

I have that feeling again.

The ‘I can’t manage alone’ feeling.

I squash it down.

I am strong. Capable. Tom and I can have a life without Olly. More importantly, we must have a life without him.

There’s no way back.

A memory unzips itself – me, crying and shaking, cowering in a bathtub as Olly’s knuckles pound on the door. Sharp and brutal.

Tears come. It will be different here.

I head up to the bathroom with its tasteful butler sink and free-standing Victorian bathtub on little wrought-iron legs. From the porcelain toothbrush holder I take hairdressing scissors – the ones I use to trim Tom’s fine, blond hair.

I pick up a long strand of my mousy old life and cut. Then I take another, and another. Turning to the side, I strip strands from my crown, shearing randomly.

Before I know it, half my hair lies in the bathroom sink.

Now I have something approaching a pixie cut – short hair, clipped close to my head. I do a little shaping around the ears and find myself surprised and pleased with the result.

Maybe I should be a hairdresser instead of a nurse, I think.

I fought so hard to finish my nurse’s training, but never did. Olly was jealous from the start. He hated me having any sort of identity.

Turning my head again in the mirror, I see myself smile. I really do like what I see. My hair is much more interesting than before, that mousy woman with non-descript brown hair.

I’m somebody who stands out.

Gets things done.

No more living in the shadows.

It won’t be how things were with Olly, when I was meek little Lizzie, shrinking at his temper.

Things will be different.

As I start tidying the house, my phone rings its generic tone. I should change that too. Get a ring tone that represents who I am. It’s time to find myself. Be someone. Not invisible, part of someone else.

My mother’s name glows on the phone screen.

Ruth Riley.

Such a formal way to store a mother’s number. I’m sure most people use ‘Mum’ or ‘Mummy’ or something.

I grab the phone. ‘Hi, Mum.’

There’s a pause, and a rickety intake of breath. ‘Did you get Tom to school on time?’

‘Of course.’

‘Because it’s important, Elizabeth. On his first day. To make a good impression.’

‘I don’t care what other people think,’ I say. ‘I care about Tom.’

‘Well, you should care, Elizabeth. You’ve moved to a nice area. The families around there will have their eyes on you. It’s not like that pokey little apartment you had in London.’

‘It was a penthouse apartment and no smaller than the house we had growing up,’ I point out. ‘We lived in a two-bed terrace with Dad. Remember?’

‘Oh, what nonsense, Elizabeth. We had a conservatory.’

Actually, it was a corrugated plastic lean-to. But my mother has never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

‘I was planning to visit you again this weekend,’ says Mum. ‘To help out.’

I want to laugh. Mum does the opposite of help out. She demands that a meal is cooked, then criticises my organisational skills.

‘You don’t have to,’ I say.

‘I want to.’

‘Why this sudden interest in us, Mum? You never visited when we lived with Olly.’

‘Don’t be silly, Elizabeth,’ Mum snaps. ‘You’re a single parent now. You need my help.’ A pause. ‘I read in the Sunday Times that Steelfield School is one of the top fifty state schools.’

‘Is it?’