Полная версия:

Economics

INFLATION has the effect of eroding the real burden of debts, which are denominated in NOMINAL VALUES. See PUBLIC SECTOR BORROWING REQUIREMENT.

burden of dependency the non-economically active POPULATION of a country in relation to the employed and self-employed LABOUR FORCE. Dependants include very young, very old and disabled members of the community, their unpaid carers and the unemployed who must rely on the efforts of the labour force to provide them with goods and services. Countries with a proportionately large dependent population need to levy high taxes upon the labour force to finance the provision of TRANSFER PAYMENTS such as pensions, child benefit and unemployment benefit.

burden of taxation see TAX BURDEN.

business a supplier of goods and services. The term can also denote a FIRM. In economic theory, businesses perform two roles. On the one hand, they enter the market place as producers of goods and services bought by HOUSEHOLDS; on the other hand, they buy factor inputs from households in order to produce those goods and services. The term ‘businesses’ is used primarily in macro (national income) analysis, while the term ‘firms’ is used in micro (supply and demand) analysis. See also CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME MODEL.

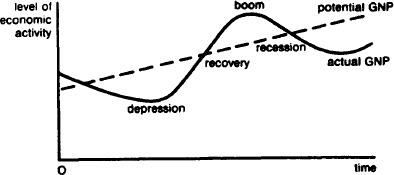

business cycle or trade cycle fluctuations in the level of economic activity (ACTUAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT), alternating between periods of depression and boom conditions.

The business cycle is characterized by four phases (see Fig. 20):

Fig. 20 Business cycle. Fluctuations in the level of economic activity.

(a) DEPRESSION, a period of rapidly falling AGGREGATE DEMAND accompanied by very low levels of output and heavy UNEMPLOYMENT, which eventually reaches the bottom of the trough;

(b) RECOVERY, an upturn in aggregate demand accompanied by rising output and a reduction in unemployment;

(c) BOOM, aggregate demand reaches and then exceeds sustainable output levels (POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT) as the peak of the cycle is reached. Full employment is reached and the emergence of excess demand causes the general price level to increase (see INFLATION);

(d) RECESSION, the boom comes to an end and is followed by recession. Aggregate demand falls, bringing with it, initially, modest falls in output and employment but then, as demand continues to contract, the onset of depression.

What causes the economy to fluctuate in this way? One prominent factor is the volatility of FIXED INVESTMENT and INVENTORY INVESTMENT expenditures (the investment cycle), which are themselves a function of businesses’ EXPECTATIONS about future demand. At the top of the cycle, income begins to level off and investment in new supply capacity finally ‘catches up’ with demand (see ACCELERATOR). This causes a reduction in INDUCED INVESTMENT and, via contracting MULTIPLIER effects, leads to a fall in national income, which reduces investment even further. At the bottom of the depression, investment may rise exogenously (because, for example, of the introduction of new technologies) or through the revival of REPLACEMENT INVESTMENT. In this case, the increase in investment spending will, via expansionary multiplier effects, lead to an increase in national income and a greater volume of induced investment. See also DEMAND MANAGEMENT, KONDRATIEF CYCLE, SECULAR STAGNATION.

Business Link a nationwide network of agencies that brings together the business support activities of many chambers of commerce, enterprise agencies, learning and skills councils and local authorities to provide a single local point of access for business information and advisory services to small and medium-sized businesses. The Business Link operates under the auspices of the SMALL BUSINESS SERVICE (SBS), an arm of the DEPARTMENT FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY (DTI). See INDUSTRIAL POLICY.

business strategy the formulation of long-term plans and policies by a firm which interlock its various production and marketing activities in order to achieve its business objectives. See FIRM OBJECTIVES, COMPETITIVE STRATEGY, HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION, VERTICAL INTEGRATION, DIVERSIFICATION.

buyer a purchaser of a GOOD or SERVICE. A broad distinction can be made between purchasers of items such as raw materials, components, plant and equipment that are used to produce other products (referred to as ‘industrial buyers’) and purchasers of products for personal consumption (referred to as ‘consumers’).

In general, industrial buyers (in the main purchasing/procurement officers) are involved in the purchase of ‘functional’ inputs to the production process, usually in large quantities and often involving the outlay of thousands of pounds. Their particular concern is to obtain input supplies that are of an appropriate quality and possess the technical attributes necessary to ensure that the production process goes ahead smoothly and efficiently. In selling to industrial buyers, personal contacts, the provision of technical advice and back-up services are important.

Buyers of consumer goods, by contrast, typically buy a much wider range of products, mainly in small quantities. Purchases are made to satisfy some ‘physical’ or ‘psychological’ need of the consumer. Thus, it is important for suppliers to understand the basis of these needs and to produce and promote BRANDS that satisfy identifiable consumer demands. In this context, ADVERTISING and SALES PROMOTION are important tools for shaping consumers’ perceptions of a brand and establishing BRAND LOYALTY. See PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION.

buyer concentration an element of MARKET STRUCTURE that refers to the number and size distribution of buyers in a market. In most markets, buyers are numerous, each purchasing only a tiny fraction of total supply. In some markets, however, most notably in INTERMEDIATE GOODS industries, a few large buyers purchase a significant proportion of total supply. Such situations are described as OLIGOPSONY, or, in the case of a single buyer, MONOPSONY.

Market theory predicts that MARKET PERFORMANCE will differ according to whether there are many buyers in the market, each accounting for only a minute fraction of total purchases, (PERFECT COMPETITION), or only a few buyers, each accounting for a substantial proportion of total purchases (oligopsony), or a single buyer (monopsony). See COUNTERVAILING POWER, MARKET CONCENTRATION, SELLER CONCENTRATION, BULK-BUYING.

buyer’s market a SHORT-RUN market situation in which there is EXCESS SUPPLY of goods or services at current prices, which forces prices down to the advantage of the buyer. Compare SELLER’S MARKET.

buy-in see MANAGEMENT BUY-IN.

buy-out see MANAGEMENT BUY-OUT.

by-product a product that is secondary to the main product emerging from a production process. For example, the refining of crude oil to produce petroleum generates a range of by-products like bitumen, naptha and creosote.

c

Cadbury Committee Report see CORPORATE GOVERNANCE.

called-up capital the amount of ISSUED SHARED CAPITAL that shareholders have been called upon to subscribe to date where a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY issues SHARES with phased payment terms. Called-up capital is usually equal to PAID-UP CAPITAL except where some shareholders have failed to pay instalments due (CALLS IN ARREARS). See SHARE ISSUE.

call money or money at call and short notice CURRENCY (notes and coins) loaned by the COMMERCIAL BANKS to DISCOUNT HOUSES. These can be overnight (24-hour) loans or one-week loans. Call money is included as part of the commercial banks’ RESERVE ASSET RATIO.

call option see OPTION.

calls in arrears the difference that arises between CALLED-UP CAPITAL and PAID-UP CAPITAL where a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY issues SHARES with phased payment terms and shareholders fail to pay an instalment. See SHARE ISSUE.

Cambridge equation see QUANTITY THEORY OF MONEY.

CAP see COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLICY.

capacity 1 the maximum amount of output that a firm or industry is physically capable of producing given the fullest and most efficient use of its existing plant. In microeconomic theory, the concept of full capacity is specifically related to the cost structures of firms and industries. Industry output is maximized (i.e. full capacity is attained) when all firms produce at the minimum point on their long-run average total cost curves (see PERFECT COMPETITION). If firms fail to produce at this point, then the result is EXCESS CAPACITY.

2 in macroeconomics, capacity refers to POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT. The percentage relationship of actual output in the economy to capacity (i.e. potential national income) shows capacity utilization. See also MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION.

capital the contribution to productive activity made by INVESTMENT in physical capital (for example, factories, offices, machinery, tools) and in HUMAN CAPITAL (for example, general education, vocational training). Capital is one of the three main FACTORS OF PRODUCTION, the other two being LABOUR and NATURAL RESOURCES. Physical (and human) capital make a significant contribution towards ECONOMIC GROWTH. See CAPITAL FORMATION, CAPITAL STOCK, CAPITAL WIDENING, CAPITAL DEEPENING, GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION, CAPITAL ACCUMULATION.

capital account 1 the section of the NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS that records INVESTMENT expenditure by government on infrastructure such as roads, hospitals and schools; and investment expenditure by the private sector on plant and machinery.

2 the section of the BALANCE OF PAYMENTS accounts that records movements of funds associated with the purchase or sale of long-term assets and borrowing or lending by the private sector.

capital accumulation or capital formation 1 the process of adding to the net physical CAPITAL STOCK of an economy in an attempt to achieve greater total output. The accumulation of CAPITAL GOODS represents foregone CONSUMPTION, which necessitates a reward to capital in the form of INTEREST, greater PROFITS or social benefit derived. The rate of accumulation of an economy’s physical stock of capital is an important determinant of the rate of growth of an economy and is represented in various PRODUCTION FUNCTIONS and ECONOMIC GROWTH models. A branch of economics, called DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS, devotes much of its analysis to determining appropriate rates of capital accumulation, type of capital required and types of investment project to maximize ‘development’ in underdeveloped countries (see DEVELOPING COUNTRY). In developed countries, the INTEREST RATE influences SAVINGS and INVESTMENT (capital accumulation) decisions, to a greater or lesser degree, in the private sector (see KEYNESIAN ECONOMICS) and can therefore be indirectly influenced by government. Government itself invests in the economy’s INFRASTRUCTURE. This direct control over capital accumulation, and the indirect control over private investment, puts the onus of achieving the economy’s optimal growth path on to the government. The nature of capital accumulation (whether CAPITAL WIDENING or CAPITAL DEEPENING) is also of considerable importance. See also CAPITAL CONSUMPTION, INVENTION, INNOVATION, CAPITAL-OUTPUT RATIO. 2 the process of increasing the internally available CAPITAL of a particular firm by retaining earnings to add to RESERVES.

capital allowances ‘write-offs’ against CORPORATION TAX when a FIRM invests in new plant and equipment. In the UK currently (as at 2004/05) a 25% ‘writing-down allowance’ against tax is available for firms that invest in new plant and equipment. Additionally, in the case of small and medium-sized firms, a 40% ‘first-year allowance’ is available for investment in new plant and equipment and a 100% tax write-off for investment in computers and e-commerce.

Capital allowances are aimed at stimulating investment, thereby increasing the supply-side capabilities of the economy and the rate of ECONOMIC GROWTH. See CAPITAL GOODS, DEPRECIATION 2.

capital appreciation see APPRECIATION 2.

capital asset pricing model a model that relates the expected return on an ASSET or INVESTMENT to its risk. Assets that show greater variability in their annual returns generally need to earn higher expected average returns to compensate investors for the variability of returns. See RISK AND UNCERTAINTY.

capital budgeting the planning and control of CAPITAL expenditure within a firm. Capital budgeting involves the search for suitable INVESTMENT opportunities; evaluating particular investment projects; raising LONG-TERM CAPITAL to finance investments; assessing the COST OF CAPITAL; applying suitable expenditure controls to ensure that investment outlays conform with the expenditures authorized; and ensuring that adequate cash is available when required for investments. See INVESTMENT APPRAISAL, DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW, PAYBACK PERIOD, MARGINAL EFFICIENCY OF CAPITAL/INVESTMENT.

capital consumption the reduction in a country’s CAPITAL STOCK incurred in producing this year’s GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT (GNP). In order to maintain (or increase) next year’s GNP, a proportion of new INVESTMENT must be devoted to replacing worn-out and obsolete capital stock. Effectively, capital consumption represents the aggregate of firms’ DEPRECIATION charges for the year.

capital deepening an increase in the CAPITAL input in the economy (see ECONOMIC GROWTH) at a faster rate than the increase in the LABOUR input so that proportionally more capital to labour is used to produce national output. See CAPITAL WIDENING, CAPITAL-LABOUR RATIO, PRODUCTIVITY.

capital employed see SHAREHOLDERS’ CAPITAL EMPLOYED, LONG-TERM CAPITAL EMPLOYED.

capital expenditure see INVESTMENT.

capital formation see CAPITAL ACCUMULATION.

capital gain the surplus realized when an ASSET (house, SHARE, etc.) is sold at a higher price than was originally paid for it. Because of INFLATION, however, it is important to distinguish between NOMINAL VALUES and REAL VALUES. Thus what appears to be a large nominal gain may, after allowing for the effects of inflation, turn out to be a very small real gain. Furthermore, in an ongoing business, provision has to be made for the REPLACEMENT COST of assets, which can be much higher than the HISTORIC COST of the assets being sold. See CAPITAL GAINS TAX, CAPITAL LOSS, REVALUATION PROVISION, APPRECIATION 2.

capital gains tax a TAX on the surplus obtained from the sale of an ASSET for more than was originally paid for it. In the UK, CAPITAL GAINS tax for business assets is based (as at 2005/06) on a sliding scale, falling from 40% on gains from assets held for under one year to 10% on gains realised after four years. For persons, capital gains on ‘chargeable’ assets (e.g. shares) up to £8,500 per year are exempt from tax; above this they are taxed at 40%.

capital gearing or leverage the proportion of fixed-interest LOAN CAPITAL to SHARE CAPITAL employed in financing a company. Where a company raises most of the funds that it requires by issuing shares and uses very few fixed-interest loans, it has a low capital gearing; where a company raises most of the funds that it needs from fixed-interest loans and few funds from SHAREHOLDERS, it is highly geared. Capital gearing is important to company shareholders because fixed-interest charges on loans have the effect of gearing up or down the eventual residual return to shareholders from trading profits. When the trading return on total funds invested exceeds the interest rate on loans, any residual surplus accrues to shareholders, enhancing their return. On the other hand, when the average return on total funds invested is less than interest rates, then interest still has to be paid, and this has the effect of reducing the residual return to shareholders. Thus, returns to shareholders vary more violently when highly geared.

The extent to which a company can employ fixed-interest capital as a source of long-term funds depends to a large extent upon the stability of its profits over time. For example, large retailing companies whose profits tend to vary little from year to year tend to be more highly geared than, say, mining companies whose profit record is more volatile.

capital goods the long-lasting durable goods, such as machine tools and furnaces, that are used as FACTOR INPUTS in the production of other products, as opposed to being sold directly to consumers. See CAPITAL, CONSUMER GOODS, PRODUCER GOODS.

capital inflow a movement of funds into the domestic economy from abroad, representing either the purchase of domestic FINANCIAL SECURITIES and physical ASSETS by foreigners, or the borrowing (see BORROWER) of foreign funds by domestic residents.

Capital inflows involve the receipt of money by one country, the host, from one or more foreign countries, the source countries. There are many reasons for the transfer of funds between nations:

(a) FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT by MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES in physical assets such as the establishment of local manufacturing plant;

(b) the purchase of financial securities in the host country which are considered to be attractive PORTFOLIO investments;

(c) host-government borrowing from other governments or international banks to alleviate short-term BALANCE OF PAYMENTS deficits;

(d) SPECULATION about the future EXCHANGE RATE of the host country currency and interest rates, expectation of an appreciation of the currency leading to a capital inflow as speculators hope to make a capital gain after the APPRECIATION of the currency.

By contrast, a CAPITAL OUTFLOW is the payment of money from one country to another for the sort of reasons already outlined. See also FOREIGN INVESTMENT, HOT MONEY.

capital-intensive firm/industry a firm or industry that produces its output of goods or services using proportionately large inputs of CAPITAL equipment and relatively small amounts of LABOUR. The proportions of capital and labour that a firm uses in production depend mainly on the relative prices of labour and capital inputs and their relative productivities. This in turn depends upon the degree of standardization of the product. Where standardized products are sold in large quantities, it is possible to employ large-scale capital-intensive production methods that facilitate ECONOMICS OF SCALE. Aluminium smelting, oil refining and steelworks are examples of capital-intensive industries. See MASS PRODUCTION, CAPITAL-LABOUR RATIO.

capitalism see PRIVATE-ENTERPRISE ECONOMY.

capitalization issue or scrip issue the issue by a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY of additional SHARES to existing SHAREHOLDERS without any further payment being required. Capitalization issues are usually made where a company has ploughed back profits over several years, so accumulating substantial RESERVES, or has revalued its fixed assets and accumulated capital reserves. If the company wishes to capitalize the reserves, it can do so by creating extra shares to match the reserves and issue them as BONUS SHARES to existing shareholders in proportion to their existing shareholdings. See also RETAINED PROFIT.

capital-labour ratio the proportion of CAPITAL to LABOUR inputs in an economy. If capital inputs in the economy increase over time at the same rate as the labour input, then the capital-labour ratio remains unchanged (see CAPITAL WIDENING). If capital inputs increase at a faster rate than the labour input, then CAPITAL DEEPENING takes place. The capital-labour ratio is one element in the process of ECONOMIC GROWTH. See CAPITAL-INTENSIVE FIRM/INDUSTRY, LABOUR-INTENSIVE FIRM/INDUSTRY, AUTOMATION.

capital loss the deficit realized when an ASSET (house, SHARE, etc.) is sold at a lower price than was originally paid for it. Compare CAPITAL GAIN.

capital market the market for long-term company LOAN CAPITAL and SHARE CAPITAL and government BONDS. The capital market together with the MONEY MARKET (which provides short-term funds) are the main sources of external finance to industry and government. The financial institutions involved in the capital market include the CENTRAL BANK, COMMERCIAL BANKS, the saving-investing institutions (INSURANCE COMPANIES, PENSION FUNDS, UNIT TRUSTS and INVESTMENT TRUST COMPANIES), ISSUING HOUSES and MERCHANT BANKS.

New share capital is most frequently raised through issuing houses or merchant banks, which arrange for the sale of shares on behalf of client companies. Shares can be issued in a variety of ways, including: directly to the general public by way of an ‘offer for sale’ (or an ‘introduction’) at a prearranged fixed price; an ‘offer for sale by TENDER’, where the issue price is determined by averaging out the bid prices offered by prospective purchasers of the share subject to a minimum price bid; a RIGHTS ISSUE of shares to existing shareholders at a fixed price; a placing of the shares at an arranged price with selected investors, often institutional investors. See STOCK EXCHANGE.

capital movements the flows of FOREIGN CURRENCY between countries representing both short-term and long-term INVESTMENT in physical ASSETS and FINANCIAL SECURITIES and BORROWINGS. See CAPITAL INFLOW, CAPITAL OUTFLOW, BALANCE OF PAYMENTS, FOREIGN INVESTMENTS.

capital outflow a movement of domestic funds abroad, representing either the purchase of foreign FINANCIAL SECURITIES and physical ASSETS by domestic residents or the BORROWING of domestic funds by foreigners. See CAPITAL INFLOW, BALANCE OF PAYMENTS, FOREIGN INVESTMENT, HOT MONEY.

capital-output ratio a measure of how much additional CAPITAL is required to produce each extra unit of OUTPUT, or, put the other way round, the amount of extra output produced by each unit of added capital. The capital-output ratio indicates how ‘efficient’ new INVESTMENT is in contributing to ECONOMIC GROWTH. Assuming, for example, a 4:1 capital-output ratio, each four units of extra investment enables national output to grow by one unit. If the capital-output ratio is 2:1, however, then each two units of extra investment expands national income by one unit. See CAPITAL ACCUMULATION, PRODUCTIVITY. See also SOLOW ECONOMIC-GROWTH MODEL.

capital stock the net accumulation of a physical stock of CAPITAL GOODS (buildings, plant, machinery, etc.) by a firm, industry or economy at any one point in time (see POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT).

The measurements most frequently used for the value of a country’s capital stock are from the NATIONAL INCOME and expenditure statistics. These statistics take private and public expenditure on capital goods and deduct CAPITAL CONSUMPTION (see DEPRECIATION 2) to arrive at net accumulation (which may be positive or negative). The more relevant value of capital stock, from the economist’s point of view, is the present value of the stream of income such stock can generate. More broadly, the size of a country’s capital stock has an important influence on its rate of ECONOMIC GROWTH. See CAPITAL ACCUMULATION, CAPITAL WIDENING, CAPITAL DEEPENING, DEPRECIATION METHODS, PRODUCTIVITY, CAPITAL-OUTPUT RATIO.

capital transfer tax see WEALTH TAX.

capital widening an increase in the CAPITAL input in the economy (see ECONOMIC GROWTH) at the same rate as the increase in the LABOUR input so that the proportion in which capital and labour are combined to produce national output remains unchanged. See CAPITAL DEEPENING, CAPITAL-LABOUR RATIO, PRODUCTIVITY.