Полная версия:

Economics

dependent variable a variable that is affected by some other variable in a model. For example, the demand for a product (the dependent variable) will be influenced by its price (the INDEPENDENT VARIABLE). It is conventional to place the dependent variable on the left-hand side of an EQUATION. See DEMAND FUNCTION, SUPPLY FUNCTION.

deposit account or time account or savings account an individual’s or company’s account at a COMMERCIAL BANK into which the customer can deposit cash or cheques and from which he or she can draw out money subject to giving notice to the bank. Deposit accounts (unlike CURRENT ACCOUNTS, which are used to finance day-to-day transactions) are mainly held as a form of personal and corporate SAVING and used to finance irregular ‘one-off’ payments. INTEREST is payable on deposit accounts, normally at rates above those paid on current accounts, in order to encourage clients to deposit money for longer periods of time. Unlike with a current account, cheques cannot generally be drawn against deposit accounts. See BANK DEPOSIT.

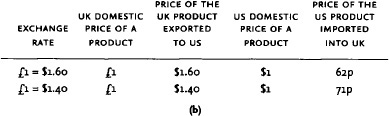

Fig. 43 Depreciation. (a) A depreciation of the pound against the dollar. (b)The effect of depreciation on export and import prices.

depreciation

1 a fall in the value of a CURRENCY against other currencies under a FLOATING EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM, as shown in Fig. 43 (a). A depreciation of a currency’s value makes IMPORTS (in the local currency) more expensive and EXPORTS (in the local currency) cheaper, thereby reducing imports and increasing exports, and so assisting in the removal of a BALANCE OF PAYMENTS deficit. For example, as shown in Fig. 43 (b), if the pound-dollar exchange rate depreciates from £1.60 to £1.40, then this would allow British exporters to reduce their prices by a similar amount, thus increasing their price competitiveness in the American market (although they may choose not to reduce their prices by the full amount of the depreciation in order to boost profitability or devote more funds to sales promotion, etc.) By the same token, the depreciation serves to raise the sterling price of American products imported into Britain, thereby making them less price-competitive than British products in the home market.

In order for a currency depreciation to ‘work’, four basic conditions must be satisfied:

(a) how successful the depreciation is depends on the reactions of export and import volumes to the change in relative prices, i.e. the PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND for exports and imports. If these volumes are low, i.e. demand is inelastic, trade volumes will not change much and the depreciation may in fact worsen the situation. On the other hand, if export and import demand is elastic then the change in trade volume will improve the payments position. Balance-of-payments equilibrium will be restored if the sum of export and import elasticities is greater than unity (the MARSHALL-LERNER CONDITION);

(b) on the supply side, resources must be available, and sufficiently mobile, to be switched from other sectors of the economy into industries producing exports and products that will substitute for imports. If the economy is fully employed already, domestic demand will have to be reduced and/or switched by deflationary policies to accommodate the required resource transference;

(c) over the longer term, ‘offsetting’ domestic price, rises must be contained. A depreciation increases the cost of essential imports of raw materials and foodstuffs, which can push up domestic manufacturing costs and the cost of living. This in turn can serve to increase domestic prices and money wages, thereby necessitating further depreciations to maintain price competitiveness;

(d) finally, a crucial requirement in underpinning the ‘success’ of the above factors and in maintaining long-run equilibrium is for there to be a real improvement in the country’s industrial efficiency and international competitiveness. (See ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM entry for further discussion.) See BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM, INTERNAL-EXTERNAL BALANCE MODEL, PRICE ELASTICITY OF SUPPLY. Compare APPRECIATION 1.

2 the fall in the value of an ASSET during the course of its working life. Also called amortization. The condition of plant and equipment used in production deteriorates over time, and these items will eventually have to be replaced. Accordingly, a firm is required to make financial provision for the depreciation of its assets.

Depreciation is an accounting means of dividing up the historic cost of a FIXED ASSET over a number of accounting periods that correspond with the asset’s estimated life. The depreciation charged against the revenue of successive time periods in the PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT serves to spread the original cost of a fixed asset, which yields benefits to the firm over several trading periods. In the period end BALANCE SHEET, such an asset would be included at its cost less depreciation deducted to date. This depreciation charge does not attempt to calculate the reducing market value of fixed assets, so that balance sheets do not show realization values.

Depreciation formulas base the depreciation charge on the HISTORIC COST of fixed assets. During a period of INFLATION, however, it is likely that the REPLACEMENT COST of an asset is likely to be higher than its original cost. Thus, prudent companies need to make provision for higher replacement costs of fixed assets. See INFLATION ACCOUNTING, CAPITAL CONSUMPTION, APPRECIATION 2.

depressed area an area of a country suffering from industrial decline, resulting in an UNEMPLOYMENT rate that is significantly higher, and a level of INCOME PER HEAD that is significantly lower, than the national average. This situation can be tackled by REGIONAL POLICIES aimed at encouraging new firms and industries to locate in the area by offering them financial and other assistance. See ASSISTED AREA.

depression a phase of the BUSINESS CYCLE characterized by a severe decline (slump) in the level of economic activity (ACTUAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT). Real output and INVESTMENT are at very low levels and there is a high rate of UNEMPLOYMENT. A depression is caused mainly by a fall in AGGREGATE DEMAND and can be reversed provided that the authorities evoke expansionary FISCAL POLICY and MONETARY POLICY. See DEFLATIONARY GAP, DEMAND MANAGEMENT.

deregulation the removal of controls over economic activity that have been imposed by the government or some other regulatory body (for example, an industry trade association). Deregulation may be initiated either because the controls are no longer seen as necessary (for example, the ending of PRICE CONTROLS to combat inflation) or because they are overly restrictive, preventing companies from taking advantage of business opportunities; for example, the ending of most FOREIGN EXCHANGE CONTROLS by the UK in 1979 was designed to liberalize overseas physical and portfolio investment.

Deregulation has assumed particular significance in the context of recent initiatives by the UK government to stimulate greater competition by, for example, allowing private companies to compete for business in areas (such as local bus and parcel services) hitherto confined to central government or local authority operators. See COMPETITIVE TENDERING.

Conversely, government initiatives can be seen to have promoted regulation insofar as, for example, the PRIVATIZATION of nationalized industries has in some cases led to greater regulation of their activities via the creation of regulatory agencies (such as Ofgas in the case of the gas industry and Oftel in the case of the telecommunications industry) to ensure that the interests of consumers are protected.

derivative a financial instrument such as an OPTION or SWAP the value of which is derived from some other financial asset (for example, a STOCK or SHARE) or indices (for example, a price index for a commodity such as cocoa). Derivatives are traded on the FUTURES MARKETS and are used by businesses and dealers to ‘hedge’ against future movements in share, commodity, etc., prices and by speculators seeking to secure windfall profits. See LONDON INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL FUTURES EXCHANGE (LIFFE), STOCK EXCHANGE.

derived demand the DEMAND for a particular FACTOR INPUT or PRODUCT that is dependent on there being a demand for some other product. For example, the demand for labour to produce motor cars is dependent on there being a demand for motor cars in the first place; the demand for tea cups is dependent on there being a demand for tea. See MARGINAL REVENUE PRODUCT, FACTOR MARKETS, COMPLEMENTARY PRODUCTS.

deseasonalized data see TIME SERIES ANALYSIS.

design rights the legal ownership by persons or businesses of original designs of the shape or configuration of industrial products. In the UK, the COPYRIGHT, DESIGNS AND PATENTS ACT 1988 gives protection to the creators of industrial designs against unauthorized copying for a period of ten years after the first marketing of the product.

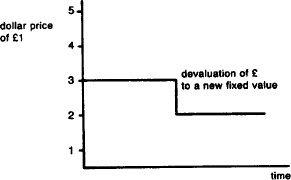

Fig. 44 Devaluation. A devaluation of the pound against the dollar.

devaluation an administered reduction in the EXCHANGE RATE of a currency against other currencies under a FIXED EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM; for example, the lowering of the UK pound (£) against the US dollar ($) from one fixed or ‘pegged’ level to a lower level, say from £1 = $3 to £1 = $2, as shown in Fig. 44. Devaluations are resorted to by governments to assist in the removal of a BALANCE OF PAYMENTS DEFICIT. The effect of a devaluation is to make IMPORTS (in the local currency) more expensive, thereby reducing import demand, and EXPORTS (in the local currency) cheaper, thereby acting as a stimulus to export demand. Whether or not a devaluation ‘works’ in achieving balance of payments equilibrium, however, depends on a number of factors, including: the sensitivity of import and export demand to price changes, the availability of resources to expand export volumes and replace imports and, critically over the long term, the control of inflation to ensure that domestic price rises are kept in line with or below other countries’ inflation rates. (See DEPRECIATION 1 for further discussion of these matters.) Devaluations can affect the business climate in a number of ways but in particular provide firms with an opportunity to expand sales and boost profitability. A devaluation increases import prices, making imports less competitive against domestic products, encouraging domestic buyers to switch to locally produced substitutes. Likewise, a fall in export prices is likely to cause overseas customers to increase their demand for the country’s exported products in preference to locally produced items and the exports of other overseas producers. If the pound, as in our example above, is devalued by one-third, then this would allow British exporters to reduce their prices by a similar amount, thus increasing their price competitiveness in the American market. Alternatively, they may choose not to reduce their prices by the full amount of the devaluation in order to increase unit profit margins and provide additional funds for advertising and sales promotion, etc. Compare REVALUATION. See INTERNAL-EXTERNAL BALANCE MODEL.

developed country an economically advanced country the economy of which is characterized by large industrial and service sectors, high levels of gross national product and INCOME PER HEAD. See Fig. 51. See STRUCTURE OF INDUSTRY, DEVELOPING COUNTRY, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT.

developing country or less developed country or underdeveloped country or emerging country or Third World country a country characterized by low levels of GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT and INCOME PER HEAD. See Fig. 51. Such countries are typically dominated by a large PRIMARY SECTOR thatproduces a limited range of agricultural and mineral products and in which the majority of the POPULATION exists at or near subsistence levels, producing barely enough for their immediate needs, thus being unable to release the resources required to support a large urbanized industrial population. The term ‘developing’ indicates that, as seen by most such countries, the way to improve their economic fortunes is to diversify the industrial base of the economy by, in particular, establishing new manufacturing industries and by adopting the PRICE SYSTEM. To facilitate an increase in urban population necessary for INDUSTRIALIZATION, a nation may either IMPORT the necessary commodities from abroad with the FOREIGN EXCHANGE earned from the EXPORT of the (predominantly) primary goods, or it can attempt to improve its own agriculture. With appropriate ECONOMIC AID from industrialized countries and the ability and willingness on the part of a developing country, the transition into a NEWLY INDUSTRIALIZED COUNTRY could be made.

Certain problems do exist, however. For instance, increases in real income that are achieved need to be maintained, which means keeping population numbers in check. Illiteracy and social customs for large families tend to work against governmental efforts to increase the STANDARD OF LIVING of its citizens. Also, most of the foreign exchange earned by such countries is by exporting, mainly commodities (see INTERNATIONAL TRADE). See ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, STRUCTURE OF INDUSTRY, DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION, POPULATION TRAP, INTERNATIONAL COMMODITY AGREEMENTS, UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT, INTERNATIONAL DEBT.

development area an area of the country formerly designated under UK REGIONAL POLICY (for example, the Northeast and South Wales) as qualifying for financial and other assistance in order to promote industrial regeneration. Development Areas reconfigured (in 2002) as ‘Tier 1 ASSISTED AREAS’ under a joint UK/EUROPEAN UNION regional policy programme. Development/Tier 1 areas are characterized by UNEMPLOYMENT rates that are significantly higher, and levels of INCOME PER HEAD that are significantly lower, than the national average. To remedy this situation, the usual practice is to encourage the establishment of new firms, the expansion of existing firms and the establishment of new industries by offering a variety of investment incentives: investment grants and allowances, tax write-offs, rent- and rate-free (or reduced) factories, etc.

In the UK, firms investing in the assisted areas are offered REGIONAL SELECTIVE ASSISTANCE, which is given on a discretionary basis to cover capital and training costs for projects that meet specified job-creation criteria.

development economics the branch of economics that seeks to explain the processes by which a DEVELOPING COUNTRY increases in productive capacity, both agricultural and industrial, in order to achieve sustained ECONOMIC GROWTH.

Much work in development economics has focused on the way in which such growth can be achieved, for instance, the question of whether agriculture ought to be developed in tandem with industry, or whether leading industries should be allowed to move forward independently, so encouraging all other sectors of society. Another controversial question is whether less developed countries are utilizing the most appropriate technology. Many economists argue for intermediate technology as most appropriate rather than very modern plants initially requiring Western technologists and managers to run them. Socio-cultural factors are also influential in attempting to achieve take-off into sustained economic growth. See ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, INFANT INDUSTRY.

differentiated product see PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION.

differentiation competition strategy see COMPETITIVE STRATEGY.

diffusion the process whereby INNOVATIONS are accepted and used by firms and consumers through imitation, licensing agreements or sale of products and patents.

diminishing average returns see DIMINISHING RETURNS.

diminishing marginal rate of substitution see MARGINAL RATE OF SUBSTITUTION.

diminishing marginal returns see DIMINISHING RETURNS.

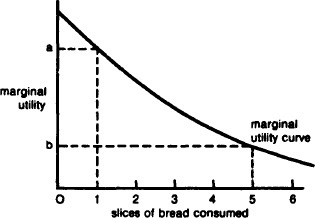

diminishing marginal utility a principle that states that as an individual consumes a greater quantity of a product in a particular time period, the extra satisfaction (UTILITY) derived from each additional unit will progressively fall as the individual becomes satiated with the product. See Fig. 45.

The principle of diminishing MARGINAL UTILITY can be used to explain why DEMAND CURVES for most products are downward sloping, since if individuals derive less satisfaction from successive units of the product they will only be prepared to pay a lower price for each unit.

Demand analysis can be conducted only in terms of diminishing marginal utility if CARDINAL UTILITY measurement is possible. In practice, it is not possible to measure utility precisely in this way, so demand curves are now generally constructed from INDIFFERENCE CURVES, which are based upon ORDINAL UTILITY. See CONSUMER EQUILIBRIUM, REVEALED PREFERENCE.

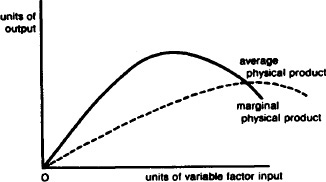

diminishing returns the law in the SHORT-RUN theory of supply of diminishing marginal returns or variable factor proportions that states that as equal quantities of one VARIABLE FACTOR INPUT are added into the production function (the quantities of all other factor inputs remaining fixed), a point will be reached beyond which the resulting addition to output (that is, the MARGINAL PHYSICAL PRODUCT of the variable input) will begin to decrease, as shown in Fig. 46.

As the marginal physical product declines, this will eventually cause AVERAGE PHYSICAL PRODUCT to decline as well (diminishing average returns). The marginal physical product changes because additional units of the variable factor input do not add equally readily to units of the fixed factor input.

Fig. 45 Diminishing marginal utility. To a hungry man the utility of the first slice of bread consumed will be high (O2) but as his appetite becomes satiated, successive slices of bread yield smaller and smaller amounts of satisfaction; for example, the fifth slice of bread yields only Ob of additional utility.

At a low level of output, marginal physical product rises with the addition of more variable inputs to the (underworked) fixed input, the extra variable inputs bringing about a more intensive use of the fixed input.

Fig. 46 Diminishing returns. The rise and fall of units of output as units of variable factor input are added to the production function.

Eventually, as output is increased, an optimal factor combination is attained at which the variable and fixed inputs are mixed in the most appropriate proportions to maximize marginal physical product. Thereafter, further additions of variable inputs to the (now overworked) fixed input leads to a less than proportionate increase in output so that marginal physical product declines. See RETURNS TO THE VARIABLE FACTOR INPUT.

direct cost the sum of the DIRECT MATERIALS COST and DIRECT LABOUR COST of a product. Direct cost tends to vary proportionately with the level of output. See VARIABLE COST.

direct debit see COMMERCIAL BANK.

direct investment any expenditure on physical ASSETS such as plant, machinery and stocks. See INVESTMENT.

directive (bank) an instrument of MONETARY POLICY involving the control of bank lending as a means of regulating the MONEY SUPPLY. If, for example, the monetary authorities wish to lower the money supply, they can ‘direct’ the banks to reduce the total amount of loan finance made available to personal and corporate borrowers. A reduction in bank lending can be expected to lead to a multiple contraction of bank deposits and, hence, a fall in the money supply. See BANK DEPOSIT CREATION.

direct labour 1 that part of the labour force in a firm that is directly concerned with the manufacture of a good or the provision of a service. Contrast INDIRECT LABOUR.

2 workers employed directly by local or central government to perform tasks rather than contracting out such tasks to private-sector companies. For example, a local authority might employ its own permanent construction workers to repair council houses rather than putting such repair work out to local firms. See VARIABLE COST, PRIVATIZATION.

direct marketing see DIRECT SELLING.

direct materials raw materials that are incorporated in a product. Compare INDIRECT MATERIALS. See VARIABLE COST.

direct selling/marketing a method of selling and buying goods and services that enables a supplier to sell direct to the final customer without the need for traditional ‘middlemen’ – wholesalers and retailers. Direct selling can be undertaken through catalogues (see MAIL ORDER) or by ‘clip-out’ coupons in newspapers, but increasingly it is being undertaken by telephone sales (e.g. telephone banking and insurance) and through e-commerce (INTERNET sales). Direct selling can provide firms with an effective means of tapping into a mass market; it can reduce BARRIERS TO ENTRY so that some small firms can offer their products alongside big-name companies; and by eliminating the ‘middleman’, selling costs and prices can be lowered, conferring COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE. Apart from lower prices, another attraction for customers is the convenience of being able to ‘shop’ from home rather than having to visit a retail outlet.

direct tax a TAX levied by the government on the income and wealth received by individuals (households) and businesses in order to raise revenue and as an instrument of FISCAL POLICY. Examples of a direct tax are INCOME TAX, NATIONAL INSURANCE CONTRIBUTIONS, CORPORATION TAX and WEALTH TAX.

Direct taxes are incurred on income received, unlike indirect taxes, such as value-added taxes, that are incurred when income is spent. Direct taxes are progressive, insofar as the amount paid varies according to the income and wealth of the taxpayer. By contrast, INDIRECT TAX is regressive, insofar as the same amount is paid by each tax-paying consumer regardless of his or her income. See TAXATION, PROGRESSIVE TAXATION, REGRESSIVE TAXATION.

dirty float the manipulation by the monetary authorities of a country’s EXCHANGE RATE under a FLOATING EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM, primarily in order to gain a competitive advantage over trade partners. Thus, the authorities could intervene in the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET to stop the exchange rate from otherwise appreciating (see APPRECIATION 1) in the face of market forces or, alternatively, they could deliberately engineer a DEPRECIATION of the exchange rate. See BEGGAR-MY-NEIGHBOUR POLICY.

discount 1 a deduction from the published LIST PRICE of a good or service allowed by a supplier to a customer. The discount could be offered for prompt payment in cash (cash discount) or for bulk purchases (trade discount). Trade discounts may be given to enable suppliers to achieve large sales volumes, and thus ECONOMICS OF SCALE, or may be used as a competitive stratagem to secure customer loyalty, or may be given under duress to large, powerful buyers. See AGGREGATED REBATE, BULK BUYING.