Полная версия:

Ghostland: In Search of a Haunted Country

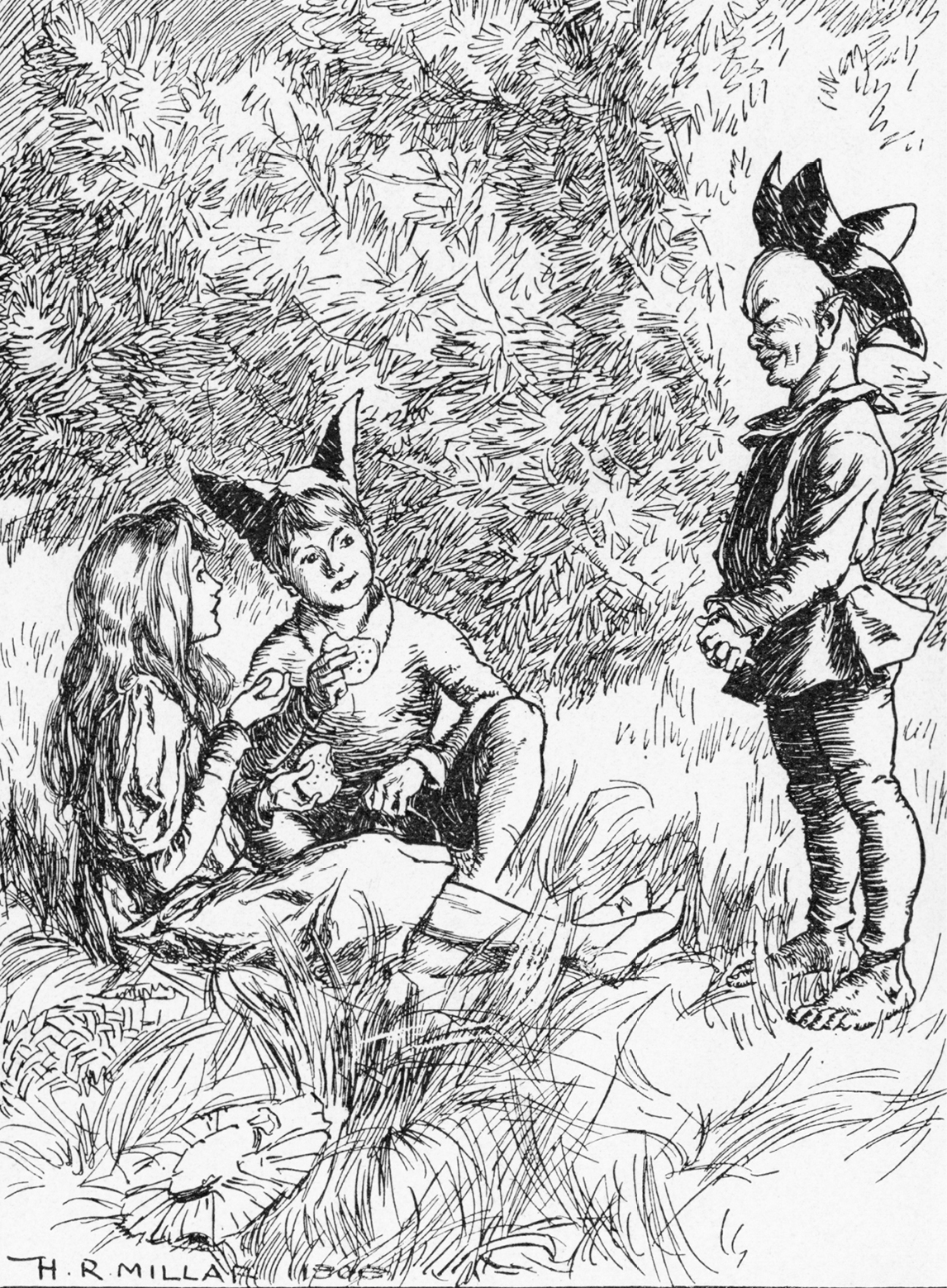

H. R. Millar (1869–1942), illustration from Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906) by Rudyard Kipling (Wikimedia Commons)

Rudyard Kipling was born in Bombay (today Mumbai) in 1862, yet educated back in England, to which he was shipped, at the age of five, by his parents. He spent the next six unhappy years being boarded with a bullying foster family in Southsea, before going on to a military school in Devon, and then returning to India where he worked as a journalist and where his first successes as a writer were to come. This was followed by further spells in London and Vermont where, by this time married, he wrote The Jungle Book. Now famous, he returned once more to Britain, settling in Torquay, and then in Sussex; these wanderings, and his troubled childhood, perhaps go some way to explaining his desire to construct his own mythic version of a history of England, the country in which he was thereafter to remain.

While on a winter visit back to the States in 1899, Kipling, along with his six-year-old daughter, Josephine, contracted pneumonia. Kipling recovered from the illness, though it took him months; his daughter – for whom he had earlier written The Jungle Book and the Just So Stories – was not so lucky. A charming gold-framed pastel drawing of young Josephine hangs in one of the bedrooms of his Jacobean Sussex house, Bateman’s – she looks out of the frame, intent on something unseen – alongside a monochrome photograph that shows the pretty, smiling little girl, then aged three, being held by her doting father.

A hint of this personal tragedy is present, I think, in Kipling’s depiction of the life-affirming Philadelphia in ‘Marklake Witches’. His younger daughter Elsie, the only one of Kipling’s three children to survive him, recalled in her memoir:

There is no doubt the little Josephine had been the greatest joy during her short life. He always adored children, and she was endowed with a charm and personality (as well as an enchanting prettiness) that those who knew her still remember. She belonged to his early, happy days, and his life was never the same after her death; a light had gone out that could never be rekindled.

In common with many other Victorian and Edwardian writers of note, Kipling occasionally turned his hand to supernatural tales, a good number of which reflected the mysticism of India. A few though take place in Kipling’s adopted Sussex, the land of Puck – among them a work of utmost poignancy that reveals the depth of his sorrow following his daughter’s death.

Kipling’s ‘They’ first appeared in the August 1904 edition of Scribner’s Magazine, and was anthologised later the same year in Traffics and Discoveries. An illustrated standalone version was published by Macmillan in 1905, which indicates the story’s popular appeal – George Bernard Shaw, for example, sent a copy of Scribner’s to the leading actress of the age, Ellen Terry, wondering whether she would consider playing the part of its main female character if Shaw could persuade Kipling to adapt the story into a play; she declined, stating that it was ‘wondrously lovely’, but that the ‘stage would be too rough for it I fear’.‡‡

In ‘They’, Kipling writes beautifully about the wooded enclaves of the Sussex countryside. Clues in the text point to the story being set somewhere around the hinterland of the village of Washington, a few miles north of Worthing and forty miles west of Bateman’s. When we are first introduced to the narrator it is very late spring, for – despite the brightness of the sun, at least where it’s able to puncture through the tunnels of hazel, oak and beech – there are reminders of the fleetingness of the seasons and the implacability of time in the already gone-over spring flowers: ‘Here the road changed frankly into a carpeted ride on whose brown velvet spent primrose-clumps showed like jade, and a few sickly, white-stalked bluebells nodded together.’

The narrator freewheels his vehicle along a leaf-strewn track, descending into sunshine and a vision of an archaic house set among a great lawn populated by topiary horsemen and their steeds. Stopping his car in the grounds of this idyll of Old Albion, the protagonist spies two children watching him from one of the house’s upper-floor windows, and hears juvenile laughter coming from behind a nearby yew peacock. The owner of the Tudor mansion appears, a redoubtable blind woman (we learn in passing that she is Miss Florence) who we half-expect to berate the motorist for his noisy intrusion. The narrator expects to be scolded too and begins his excuses about taking a wrong turn, though the lady isn’t at all bothered, and instead hopes an automobile demonstration can be put on for the elusive children.

‘Then you won’t think it foolish if I ask you to take your car through the gardens, once or twice – quite slowly. I’m sure they’d like to see it. They see so little, poor things. One tries to make their life pleasant, but –’ she threw out her hands towards the woods. ‘We’re so out of the world here.’

After driving his host around the grounds the visitor departs. When he returns again a month later, by which time the trees are in verdant full leaf, his car develops a fault in the woodland not far from the house, and he makes a noisy show of repairs, hoping it might entice in and amuse the shy youngsters. The blind proprietress instead appears and the two chat good-naturedly, though the narrator thinks he is being left out of some enormous secret by the lady and the little ones, who have by now gathered stealthily behind a bramble bush with their fingers held to their lips. Any revelation is halted by the arrival of a lady from the village, Mrs Madehurst, the owner of the shop; it transpires her infant grandson is seriously ill, and so the motorist volunteers to use his vehicle to fetch a doctor, before being enlisted on an extended expedition to taxi in a nurse.

When the narrator returns for a third and final time, autumn is beginning to set in on the hills and woods, with a chill fog permeating well inland. Kipling writes of the change that has come upon the natural world: ‘Yet the late flowers – mallow of the wayside, scabious of the field, and dahlia of the garden – showed gay in the mist, and beyond the sea’s breath there was little sign of decay in the leaf.’ En route he calls in to the shop, where he is met with Mrs Madehurst’s tears: young Arthur died two days after the nurse was brought. His mother Jenny, the shopkeeper’s daughter, is out now walking in the wood.

‘Walking in the wood’ – it’s an expression repeated by various locals throughout the story, and whose meaning will soon become clear.

Pressing on, the visitor reaches the house, proceeding within for the first time. There are signs of the recently present children everywhere in their hurriedly discarded toys.§§ His hostess takes him on a tour of the place, which is every bit as beautiful inside as out. The pair of them pass through the attic rooms set aside for the children, who remain out of vision. Finally, he spies them in the hall, hiding behind an old leather screen, and wonders whether today he will be introduced. While he sits in front of the grand, comforting fire (kept always lit for the little ones), there is a diversion as the lady of the house deals with one of her tenant farmers, Mr Turpin – a latter-day highway robber of sorts – who is trying to take advantage of his landlady by getting her to fund him a new cattle shed. In business though she’s far from unsighted, and Turpin, who throughout appears in a state of unbridled anxiety at being in the house, is sent off with nothing. While this is going on the narrator continues to try to attract the attention of the skulking infants:

I ceased to tap the leather – was, indeed, calculating the cost of the shed – when I felt my relaxed hand taken and turned softly between the soft hands of a child. So at last I had triumphed. In a moment I would turn and acquaint myself with those quick-footed wanderers …

The narrator’s patience has been rewarded, though the gift is a dubious one. His utter despair conveys an authenticity that reflects Kipling’s personal and recent familiarity with bereavement. Of the loss of his Josephine.¶¶ ‘Then I knew. And it was as though I had known from the first day when I looked across the lawn at the high window.’

For this, and its studied, unsentimental build-up and beautifully constructed setting, there are few short stories (ghost or otherwise) that come close to so perfectly expressing the kind of sadness and grief that is on display in ‘They’. The visitor ‘from the other side of the county’ finally accepts why the children are there, and what they are – all that has gone before was wilful self-delusion on his part. Yet even though by this point we too have surely worked out their nature, the story’s denouement is still devastatingly sad: our narrator is hit with the certainty that the hand which grasps his own belongs to his late daughter, and that he must never return to this shade-filled house again.

He has learned what the villager meant when she spoke of ‘walking in the wood’. It is what the bereaved do to commune with their departed.

* Deadly nightshade’s Latin name belladonna is thought to have derived from one of the plant’s medicinal properties – extracts employed in eye-drops were historically used by women to dilate their pupils and enhance the attractiveness of their eyes.

† Arkham is a fictional Massachusetts university town that features in a number of H. P. Lovecraft’s tales.

‡ Sir Stafford Northcote served as Chancellor of the Exchequer under Disraeli, between 1874 and 1880.

§ Quite probably in a deliberate nod, Northcote here employs a phrase – ‘infinite distance’ – that is also used memorably in M. R. James’s ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’.

¶ You had to press a button on the top of the phone before making a call, and check that the house across the lane wasn’t on the line at the same time. To me as a sophisticated town-dweller this ‘party line’ seemed hilariously primitive.

** Brooke won a scholarship to study at King’s College, Cambridge in 1906, a year after M. R. James became its provost. Brooke’s death in 1915 was not the result of a bullet fired by a German sniper, but from sepsis caused by an infected mosquito bite while the naively patriotic twenty-seven-year-old waited to see action with the Royal Navy. James spoke warmly about Brooke in that year’s Vice-Chancellor’s oration, his words echoing those he had earlier written about James McBryde. ‘No one, I think, must call that short life a tragedy which was so fully lived, and spent itself so generously upon all who came in contact with it.’

†† Rewards and Fairies is also notable for containing the first appearance of Kipling’s most famous and popular poem ‘If—’, which topped the survey of Britain’s favourites; ‘The Way through the Woods’ came forty-eighth.

‡‡ Terry’s last theatre role – in 1925, a little less than three years before her death at the age of eighty-one – happened to be a non-speaking performance as the ghost of Miss Susan Wildersham in Walter de la Mare’s now-obscure ‘fairy play’ Crossings.

§§ The youngsters have, I think, something about them of the playful shyness of Tolly’s elusive Restoration ancestors in The Children of Green Knowe.

¶¶ Kipling would also go on to lose his son prematurely. Eighteen-year-old John was shot in the head at the end of September 1915, while serving in France; the boy’s poor eyesight would have rendered him ineligible for active service, but he persuaded his father to pull strings to get him enlisted in the Irish Guards. Two days before his death, knowing he was about to be sent to the front, John wrote home: ‘This will be my last letter most likely for some time.’

Chapter 4

THE ROARING OF THE FOREST

A coil of movement down by the path. It’s not easy to pick out, as the leaf-heavy branches of an ancient oak cast the forest floor in shadow, but something is there. Something flesh and blood.

‘A snake,’ whispers my brother to my dad.

‘Don’t get too near, just in case.’

And now it becomes apparent not merely that this is a solitary two-and-a-half-foot grass snake, but that its mouth is crudely clamped around a shape – the back of a still-moving frog – which is gulping and blinking with a resigned calmness as the reptile stretches its jaw the final inch and envelops the amphibian’s head. Saliva bubbles from the taut corners of the snake’s mouth, and the frog lets out a high-pitched squeak.

I imagine this is roughly how it happened, because I was not a first-hand witness to this demonstration of nature’s brutality, but was playing a few hundred yards away with Mum in a New Forest car park as my dad and brother made their discovery. On their return, though, my jealousy was palpable – I’d never even seen a live snake in the English countryside before, let alone one performing a gruesome act resembling something from Life on Earth. We all set back out together into the hazy greenness of the late-summer woods, only to find the Eden beneath the oak empty, the unseen serpent watching us through the undergrowth.

The day before, we’d arrived at the end of a narrow track where our bed-and-breakfast was located – a two-storey cottage hung with weather-bleached deer skulls – just as an enormous pig was ambling around the dusty yard. In my memory, the setting came to resemble something out of an American horror film like The Evil Dead, though I supposed I’d accorded it a far more backwoods-gothic atmosphere than the reality until years later when my brother and I stumbled upon the place, its brickwork unchanged and still antler-ridden, as we searched for rare honey buzzards in the forest’s depths. I’ve been obsessed with these wasp-eating raptors – special feathering on their head helps safeguard them from stings – from the moment a pair I never managed to witness was rumoured to be nesting in a wood close to Nan’s house in Norfolk. At the time it was a species I had yet to see anywhere, but the birds – if they ever existed at all – eluded me for the fortnight I was there, despite a handful of spurious half-sightings that I tried to convince myself might be the real thing.

If the exterior of this lonely farm cottage was somewhat off-putting, then the inside was worse: ramshackle and dirty, so that Dad took the anarchic step of piling us straight back into the car and doing a flit, driving to the tourist office in Lyndhurst where alternative accommodation was found. The new guest house was better in the eyes of my parents – no dead trophy animals at least – but in my opinion (with which my brother agreed) it was spookier. The out-of-time bedroom the two of us shared was inhabited by three antique china dolls; Chris had to get up and twist them towards the wall, because we both found them menacing. It didn’t help that our bedtime reading included Chris’s newly purchased copy of Raymond Briggs’ nuclear Armageddon parable When the Wind Blows, or that it was stiflingly hot – the whole 1983 holiday, which had encompassed a grand tour of England’s south-west, was sun-baked, everywhere the grass dying and brown, like Leo’s fateful summer in The Go-Between. At regular intervals my brother called out ‘cold pillow’, an instruction to turn over our head supports in an attempt to claim temporary relief from the oppressiveness, and an opportunity to check that the staring dolls were still facing the other way. The landlady was frightening too, an old woman with bleached hair and excessive make-up – she had something of the artificial appearance of a porcelain figurine herself – who, my parents joked, looked like Bette Davis in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

I had no idea who they were talking about, though I would have if they’d namechecked The Watcher in the Woods. I’d seen this Disney children’s horror film – set in England, it was filmed largely at Pinewood Studios and in the surrounding Buckinghamshire countryside – the previous year with two of my classmates. To my shame, that night after the cinema I’d had trouble sleeping. My companions felt the same, I was relieved to learn, as we joked with daylight bravado about the movie at school the following Monday, having had the whole weekend to muse over it. The main source of our thankfully short-lived terror did not stem from Bette Davis’s creepy performance, but from the film’s copious use of tracking shots through the branches, captured from the voyeuristic perspective of the watcher and accompanied by a dramatic, jarring orchestral score. As my friends and I watched the film in our local Odeon – a building that was to close soon after, looming empty and abandoned for the next four years like the ominous pavilion in Carnival of Souls – we were left with a genuine fear that something malevolent was in the trees, unobserved yet observing us.

Like that frog-swallowing snake I would later fail to find.

The name ‘New Forest’ is something of a misnomer, as it is clearly anything but new, and large swathes of it consist of wide-open gorse- and heather-filled heathland, rather than the dense fairy-tale forest that is my landscape of memory from that family holiday. The region’s poor soils have supported this mixture of lowland heath and woodland since well before 1079, when William the Conqueror declared the area to be his Nova Foresta, a stretch of land reserved for the pursuit of deer and wild boar by the monarch (the original meaning of the word ‘forest’ is hunting ground, and maiming physical punishments were meted out to commoners caught breaking the rules).

The first Norman king’s successor, his ruddy-faced son William Rufus, was killed in the forest in August 1100, shot through the breast by a rogue arrow supposedly aimed at a stag by one of his companions (though assassination is not out of the question). William Rufus’s older brother Richard had also died some years previously in a hunting accident in his father’s preserve. And three months before, in May 1100, the king’s illegitimate nephew had likewise been slain hereabouts by another arrow gone awry. These two earlier incidents should perhaps have served as a warning to the country’s new ruler about the hazards, if not of the forest itself, then of his chosen pastime. But, even if the memory of how his relatives had met their end no longer weighed upon William II, various contemporary warnings and omens do appear to have had an effect and led the king to postpone the departure of his ill-starred stag hunt. However, this was to delay his doom for just a few short hours.

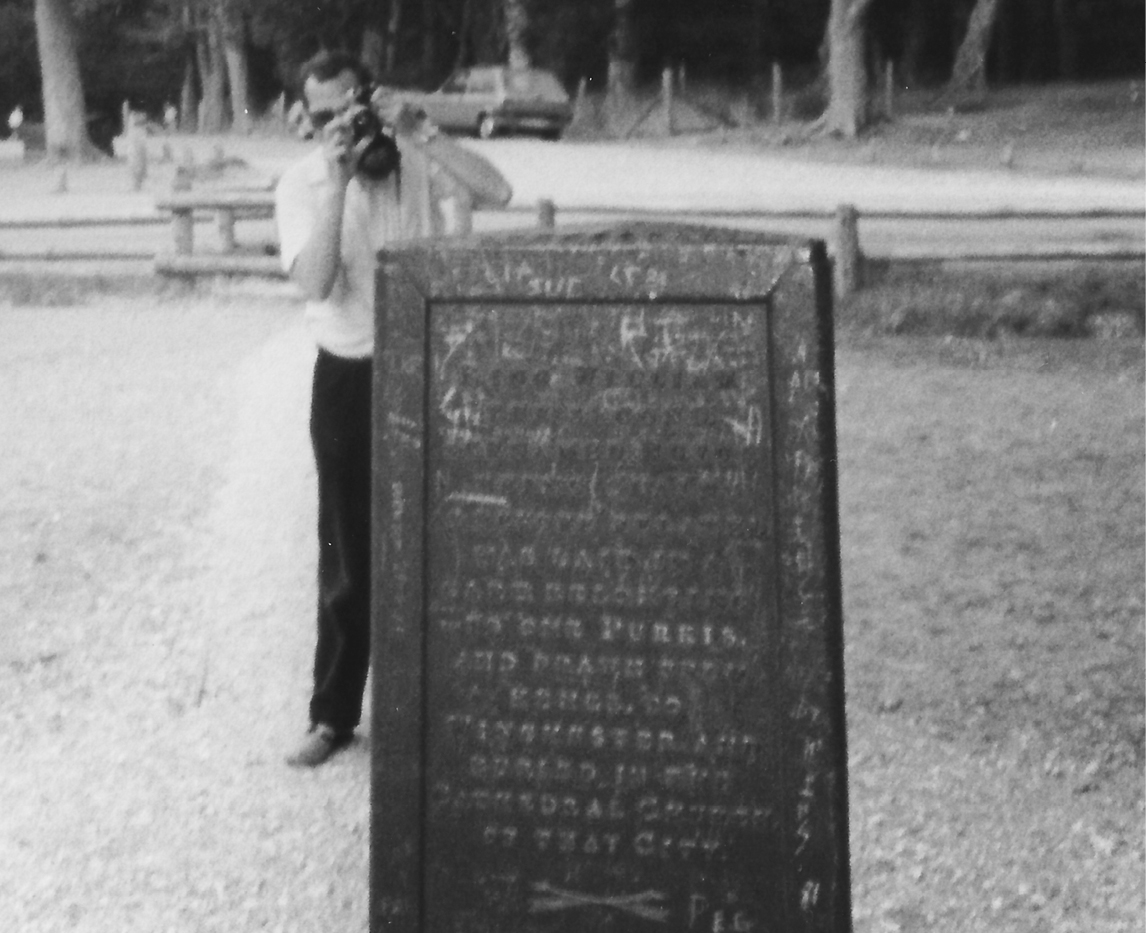

We visited the Rufus Stone, which marks the spot of the regicide, during that same sunburnt summer: the original stone, according to the 1841-erected replacement, was ‘much mutilated, and the inscriptions on each of its three sides defaced’. Among my box of old family photos and slides I can find only a solitary picture of the marker post – an image of my father engaged in the act of capturing the monument on film; the photo possesses a grainy, otherworldly hue that now would have to be digitally fabricated by some Instagram or iPhone filter. In more recent years the unobtrusive turnoff on the A31 has beckoned me to the place every time I’ve passed it on my way to see my brother at his nearby Dorset home.

Today is different – I’m heading in the opposite direction and there is no prospect of the two of us meeting later and searching the skies for twist-tailed honey buzzards. Before, though, I have often given in and broken my long journey, turning across the busy dual carriageway to absorb the atmosphere of the forest around the monument, wondering if this was also where Dad and Chris happened upon their infamous serpent. If so, perhaps another less grand marker would now be appropriate?

That the spot where an event so memorable might not hereafter be forgotten – close to here a man and his son watched a grass snake devour a fully grown frog.

Philip Hoare’s book England’s Lost Eden relates the strange events and portents surrounding the death of William Rufus in wonderful detail, before going on to catalogue the hypnotic attraction that the mysterious, superstition-filled Arcadia offered towards the end of the Victorian age to those who came here seeking a higher plane. He tells of how the forest became host to Mary Ann Girling, a farm labourer’s daughter from Suffolk who claimed to be the stigmata-scarred Messiah, but ended up encamped in increasing squalor with her rag-tag band of followers outside the village of Hordle; their Rapture never did arrive, just starvation and disappointment and, for Mary Ann, the cancer of the womb that would kill her.

At the same time as Mary Ann’s New Forest Shakers were attracting day-tripping tourists to gawk at their sorry spectacle, an eccentric Spiritualist barrister, Andrew Peterson, channelled the ghost of Sir Christopher Wren at séances and built a monument to the lure of the esoteric at nearby Sway. Today, as I walk along the narrow lane at its base, the 218ft folly – believed still to be the tallest non-reinforced concrete structure in the world – seems somewhat forlorn, squeezed in among houses and bungalows and crying out for a grander backdrop. Glimpsed, however, from a distance, jutting above the breeze-blown trees, its incantatory effect remains undiminished.

A mile and a half south-east of the Rufus Stone is Minstead. At the back of the village’s delightfully ramshackle, red-brick All Saints’ Church lies the grave of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, another who found comfort in the forest, drawn to Spiritualism after the death of his eldest son Kingsley, who was wounded at the Somme and died in 1918 from the resulting complications. The originator of Sherlock Holmes had famously been taken in by the fairies photographed by two girls, sixteen-year-old Elsie Wright and her nine-year-old cousin Frances Griffiths, at Cottingley near Bradford. The images came to Doyle’s attention via the Theosophical Society, and he broke the sensational story in a December 1920 article in The Strand magazine; the women finally confessed to the fakery more than sixty years later, long after Doyle had printed his full investigation of the pictures in his book The Coming of the Fairies. Doyle maintained that ‘there is enough already available to convince any reasonable man that the matter is not one which can be readily dismissed’, albeit adding that: ‘I do not myself contend that the proof is as overwhelming as in the case of spiritualistic phenomena.’

Glenn Hill/Contributor via Getty Images

By this late point in his life Doyle’s faith in Spiritualism was seemingly without scepticism. He was by no means alone in his beliefs, as the unprecedented slaughter of European youth that had taken place during the First World War had led to an upsurge of interest from those of the bereaved who wished to attempt communication with their dead loved ones. In 1927 Doyle published Pheneas Speaks, a catalogue of comforting messages received from the other realm at private family séances by his second wife Jean, who acted as medium. Pheneas was their third-century BC Mesopotamian spirit guide, who directed first Jean’s automatic writing (referred to as ‘inspired writing’ by Doyle) and later ‘semi-trance inspirational talking’. Many of these séances were held at their mock-Tudor New Forest retreat, Bignell House, a couple of miles east of the Rufus Stone; Pheneas even requested a room of his own in the cottage, decorated in mauve, which would psychically lend itself to ‘clearer vibrations’. The family conferred with departed relatives including their late, war-wounded son Kingsley, and Doyle’s brother-in-law – the novelist E. W. Hornung (husband of Doyle’s sister Connie), author of the Raffles ‘gentleman thief’ stories and a renowned non-believer in Spiritualism while alive. John Thadeus Delane, a former editor of The Times who had died in 1879 – a person and name, according to Doyle, apparently ‘quite unknown to my wife’ – also appeared in the ether for a chat. When asked whether he still edited a paper in the next world, Delane replied: ‘There is no need here. We know everything. It is like wireless in the air, and all so much bigger and larger and so splendid. It is great, this life.’