Полная версия:

Ghostland: In Search of a Haunted Country

As the woman leaves, she steps on a weak spot on the bank and falls into the water directly above the tunnel. She doesn’t surface and the man stands half-heartedly poking a stick into the depths below – like one of the lads in Lonely Water – before fleeing across a neighbouring field. Peter concludes that the woman must have swum further along the river and emerged while he was watching the man’s cursory search. Pleased the equilibrium of his exclusive waterway has been restored, Peter makes a final dive. Reaching the entrance to the cave-like feature he finds it blocked: ‘His fingers slid on something soft; his dive carried him violently against a heavy mass. The impact swung it a little away, but then, as he crumpled on the bottom, it bore down on him from above with dreadful, leisurely motion.’ Kicking hard he manages to free himself: ‘The mystery of how the woman left the river without a trace was solved. She had never left it, she was down at the bottom, out of sight.’

Peter returns home and mentions nothing about the incident to his parents or friends, even when weeks later it’s revealed that a blacksmith from a nearby village has been found in connection with the woman’s murder and is likely to hang. He realises a miscarriage of justice is about to occur but still doesn’t say anything. We are left with the chilling image of his corrupted waterway: ‘Those two had done something to the river. He couldn’t swim there any more, his skin crept at the thought of the brown water, the soft, pulpy mud. And the underwater tunnel – it belonged to the fat woman now.’

Peter abandons his former haunt, in future joining the other boys who swim in the nearby quarry. He has developed a vital childhood coping mechanism, one that most of us, at some point I think, have employed: ‘He had the weapon of youth, the power to bury deep that which was more profitably forgotten.’

Certainly, I have.

I follow the Welland the few miles to where it runs into the bird-rich basin of the Wash. Today there are well-appointed nature reserves nearby at Frampton and Freiston, complete with proper hides and even a visitor centre. However, when I was growing up ‘the Marsh’ meant the esoterically named Shep Whites – the lonesome southern stretch of shore that stretches from the mouth of the river to just north of the village of Holbeach St Matthew. (Rather mundanely, ‘Shep’ White was a local shepherd who ended up making his home beside the sea wall.) Occasionally, we used to go to the marsh at weekends when I was small, though I could never memorise the labyrinthine set of narrow single-track roads that Dad plotted a course through to get us there – they seemed to change each time we visited.

Locating a route remains as difficult but, fittingly, for the final winding stretch Lou Reed’s ‘Halloween Parade’ shuffles into play on my phone through the speakers of my radio – my brother’s cassette tape of the 1989 album New York on which the song appears was an ever-present fixture in the car we shared at the start of the 1990s. This track, with its elegiac roll-call of those lost to Aids, seems particularly poignant today, putting me in mind of earlier visits and faces I too will never see again. Finally, assisted by the sight of a particular Second World War pillbox, and finding the familiar crucial left turn, I arrive at the makeshift parking area behind the sea wall. It’s tattier than I remember, a fly-tipper’s paradise with a broken-open piano littering the scrub, its redundant loose keys strewn among the long grass.

I used to love the anticipation before you ran up the grassy bank: would the tide be in so that you’d feel yourself standing at the seaside, or would you be confronted with a green-and-brown expanse of mud and saltmarsh, the distant water barely visible at the edge of your vision? In the summer the landscape seemed kinder, its harsh edges softened by the pale blooms of cow parsley that grew rampantly along the dykes. My grandad called it ‘kek’, and one of his sluice-keeping tasks would be to burn off it and the other weeds that would clog the drainage ditches later in the season; in his eighties and early nineties, when I drove him around his old stamping ground, he would wistfully point out tinder-dry stands of dyke-side grasses he’d like to put a match to.

Peering into the distance you could see the shimmer – a sort of Fata Morgana – of ghostly half-real structures further round the coast. Like the ugly squat slab of the Pilgrim Hospital, the name honouring the group of Christian separatists who, in 1607, attempted to sail from the port of Boston to find religious freedom in the Netherlands (and later the New World), only to be betrayed by their skipper and end up imprisoned in the town’s guildhall. Or the 272 foot ‘Stump’ of Boston’s towering church, where in September 1860 an ominous-seeming cormorant alighted, its arrival presaging the simultaneous sinking a continent away in Lake Michigan of the Lady Elgin and the loss of 279 souls, including the town’s MP, Herbert Ingram (who also happened to be the founder of The Illustrated London News), and his fifteen-year-old son.¶

The unfortunate, portentous bird was shot the next morning, the badly stuffed specimen spending the following forty years on display in a local pub before being mislaid and vanishing from view.

One time, as a teenager, I came here late at night with my friend Piete – the spelling of his name reflecting the area’s Dutch history – after we’d liberated ourselves from the constraints of small-town existence by passing our driving tests. The parking area was empty, illuminated by the full moon, but we didn’t linger long after stepping from the car because the cacophony coming over the sea wall from the roosting curlews and oystercatchers seemed amplified to an unnatural degree, like the ‘strange cries as of lost and despairing wanderers’ that M. R. James describes in ‘Lost Hearts’. Later, while at university, I visited with my girlfriend at dusk and we became spooked by the weird greenish tone that the sky over the Wash had taken on: the vista lends itself to such fancies. Now I think it must have been the northern lights pushed far to the south due to an unusually high level of solar activity.

Today, as on most of my impromptu visits, the water is way out. The sky is ashen, the panorama drab. A few brent geese, small dark-bellied wildfowl that winter in East Anglia and breed in western Siberia, are flying over the far mudflats; their name is thought to be derived from the Old Norse word brandgas, denoting ‘burnt’ – a reference to the species’ dusky colouring. I follow the sweep of the sea bank around to my left. On the inland side the amorphousness of the marsh gives way to an artificial angularity: vast arable fields punctuated by ragged hedges and occasional coverts, bisected by wide drainage ditches. It’s quiet, the only sound the familiar piping whistle of a lone redshank that flicks up from a creek.

As well as being a childhood Sunday afternoon ride out, this place was later to become a regular hangout for my brother and me, though by then we’d learnt to try and time our visits to coincide with the rising waters, arriving an hour or so before the waves were at their height, when the birds would be pushed up onto the small artificial spit of land that extends out from the pumping house. Once a tame common seal lolled in the water a few feet away, eyeing us curiously, while on other fortunate occasions we sat entranced as whirlwinds of waders newly arrived from their Scandinavian and Arctic breeding grounds, settled close by in the late-summer sunshine.

Surprisingly, this very spot was also chosen as a location for the somewhat underwhelming 1992 adaptation of Waterland. The nondescript brick pumping station was temporarily transformed into a Victorian two-storey, tile-roofed sluice-keeper’s cottage. Chris and I pushed Mum, now in a wheelchair like her mother before her, along this same stretch of bank soon after filming had finished in the autumn of 1991, the three of us impressed by the sham house in our midst; on the way back to the car, we paused to look at a fresh-in fieldfare – a wintering migrant thrush from northern Europe, its name literally meaning ‘the traveller over the field’ – that landed, cackling, on the barren ploughed ground across the dyke. Watching the film at the cinema the following year – though Mum was not with us to see it – it was hard to suspend disbelief at the Cricks in their illusory cottage, or when Jeremy Irons ascended in a few steps from what was obviously the inland Cambridgeshire Fens to these desolate coastal saltmarshes.

I stand on the bank contemplating my own history, studying the curve of two parallel creeks that meander towards the promise of the sea. I came here with my cousin a day after my dad died, to try to kill some of the empty, dragging time before the funeral. In the edgeland adjacent to the car park, a migrant grasshopper warbler – for once not skulking at the back of some reedbed – was balanced on top of a bramble, from where it delivered its song with gusto: a high-frequency staccato my ears would now strain to hear, the sound like a fishing line being reeled in. Across the mud shimmered the brooding, blocky mirage of the Pilgrim Hospital, which my father had entered a few weeks before and never left.

For me this is a melancholy place, haunted by the ebbs and flows of its past associations.

In the final paragraph of Waterland, as Tom Crick scans the surface of the Great Ouse for his lost brother, Swift surely alludes – ‘We row back against the current …’ – to one of the great last lines of literature, and a book, The Great Gatsby, I was to study a few months after wheeling my mother in her chair along the bank, all those memories ago: ‘So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.’

Out on the Wash a group of shrimp trawlers cluster together in what is left of the dying daylight.

I shall not rush to return.

Seven miles as the brent goose flies, though a winding eighteen by car, and I am between a white lighthouse and the canal-straight channel of the Nene. ‘Down here the river has a surging life of its own, compensating (for those attuned) for the flatness of the surrounding country,’ states Robert Aickman, author of forty-eight hard-to-classify ‘strange tales’ and also, perhaps somewhat incongruously, the co-founder of the Inland Waterways Association.** The building before me is Sutton Bridge’s East Lighthouse; its near-identical twin is located on the opposite bank. Built between 1829 and 1833 and designed by John Rennie, the architect of Waterloo Bridge, to delineate the river’s mouth, the East Lighthouse was an early home of the conservationist Peter Scott, son of the ill-fated Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Aged twenty-four, Scott arrived at this secluded stretch of river in 1933 to find a purpose for himself; he was to live here, on and off, for the next six years. It was the place where he honed his wildlife painting and wrote his first two books, and where he kept his original collection of wildfowl on the expansive pools that used to be found on the saltings between the lighthouse and the Wash.

Those tidal lagoons have long gone, reclaimed in the 1960s and 70s into arable fields that stretch as far as you can see. My father brought me here one Sunday afternoon to an open day being held by the local farmer, and often we would detour along the top of the Nene’s east bank on the way back from visiting my grandmother in Norfolk. Later Dad got me a summer job alongside my brother at a nearby, dusty vegetable-canning factory; we looked out over the wavering wheat towards Scott’s erstwhile home as we stacked boxes of tinned baked beans bound for Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, while the shed’s sole soft-rock cassette compilation, Leather and Lace, played in a never-ending loop. That summer was among my best times, I sometimes think, even though the work was tedious and physically challenging – I was sixteen and my world was awash with possibilities, had yet to start coming apart.

Despite the transformation of Scott’s marshland, there are still a couple of ponds behind the lighthouse that hold a remnant selection of exotic waterbirds, including a pair of beautiful red-breasted geese and a sextet of sneering snow geese (a line of black that contrasts with the pink of the rest of the bill – the so-called ‘grinning patch’ – really does give the snow goose a contemptuous expression). This latter North American species gave the title to the bestselling novel by Paul Gallico, who loosely based his story of a reclusive lighthouse-dwelling painter on Scott and a wild pink-footed goose that, in 1936, took up residence among the lighthouse’s fledgling bird collection, returning again in following winters.††

Robert Aickman’s guide to boating holidays, Know Your Waterways, also namechecks Scott’s lighthouse as a notable landmark. Aickman knew Scott – who happened, in addition, to write the introduction to Aickman’s barge book – and the two men, surprisingly, remained friends after Scott’s first wife, the writer Elizabeth Jane Howard, left the conservationist in August 1947 for the thickly bespectacled and besotted Aickman. The couple’s relationship itself ended a little over four years later (in Howard’s memoir Aickman comes across as a rather jealous and controlling figure), though not before the couple had collaborated on a debut 1951 collection of supernatural stories, We Are for the Dark. Each of them contributed three tales, including Howard’s supremely ominous ‘Three Miles Up’, my favourite in the slim volume, which displays the enigmatic qualities we now regard as key characteristics of an ‘Aickman-esque’ story – pointing perhaps to the uncredited influence that Howard’s writing was to have on her lover as, mainly during the 1960s and 70s, he wrote the majority of his critically lauded work. ‘Three Miles Up’ seems autobiographical in its depiction of a narrowboat journey gone awry, and possibly prefigures the rivalries and eventual falling out between Aickman and Tom Rolt, as well as Howard and Aickman’s own parting soon after the publication of their joint collection. The story’s ending offers a purgatorial, nightmare-inducing vision that’s hard to beat:

The canal immediately broadened, until no longer a canal but a sheet, an infinity, of water stretched ahead; oily, silent, and still, as far as the eye could see, with no country edging it, nothing but water to the low grey sky above it.

The unspecified inland English canal setting of ‘Three Miles Up’ was relocated to the Fens in an effective, though loose BBC adaptation of Howard’s story, with the transformation of the central male characters into a pair of estranged brothers, and the addition of a supernatural whistle that could be straight out of M. R. James’s ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’. The drama’s final scenes were shot at the mouth of my own River Welland, the waterway that flowed along the top of my street and which I crossed each day on my walk to school. The crew had only a risky two-hour window, the director Lesley Manning tells me, filming where the river enters the Wash downstream of my grandfather’s Seas End bungalow and adjacent to the marshes of Shep Whites. Those inundated mudflats make a good match for the ‘infinity’ of water that opens out before the reader at the story’s grim conclusion.‡‡

The Nene flowing hurriedly before me now, which has dropped precipitously on the retreating deluge to reveal sludgy cliff-like banks, has its source in Northamptonshire, and runs through an artificially straightened channel past Peterborough, where it becomes tidal. The river’s outfall was completed around 1830, with 900 men and 250 horses labouring to dig out the last seven-mile stretch that replaced the meandering former route. And although in Waterland’s final act Graham Swift has Tom Crick and his father scanning the waters of the Great Ouse – located a few miles away at King’s Lynn – for a sign of his drowned brother Dick, the adaptation of Swift’s novel shot the scene here on the Nene, with Scott’s old lighthouse appearing briefly in frame. The mud of the river and the marshes around Sutton Bridge is often also cited as a possible resting place of King John’s fabled lost treasure. The story finds its way into a book partly set around these same creeks and channels that is regarded by many M. R. James devotees as one of the few great novels in his tradition: The House on the Brink.

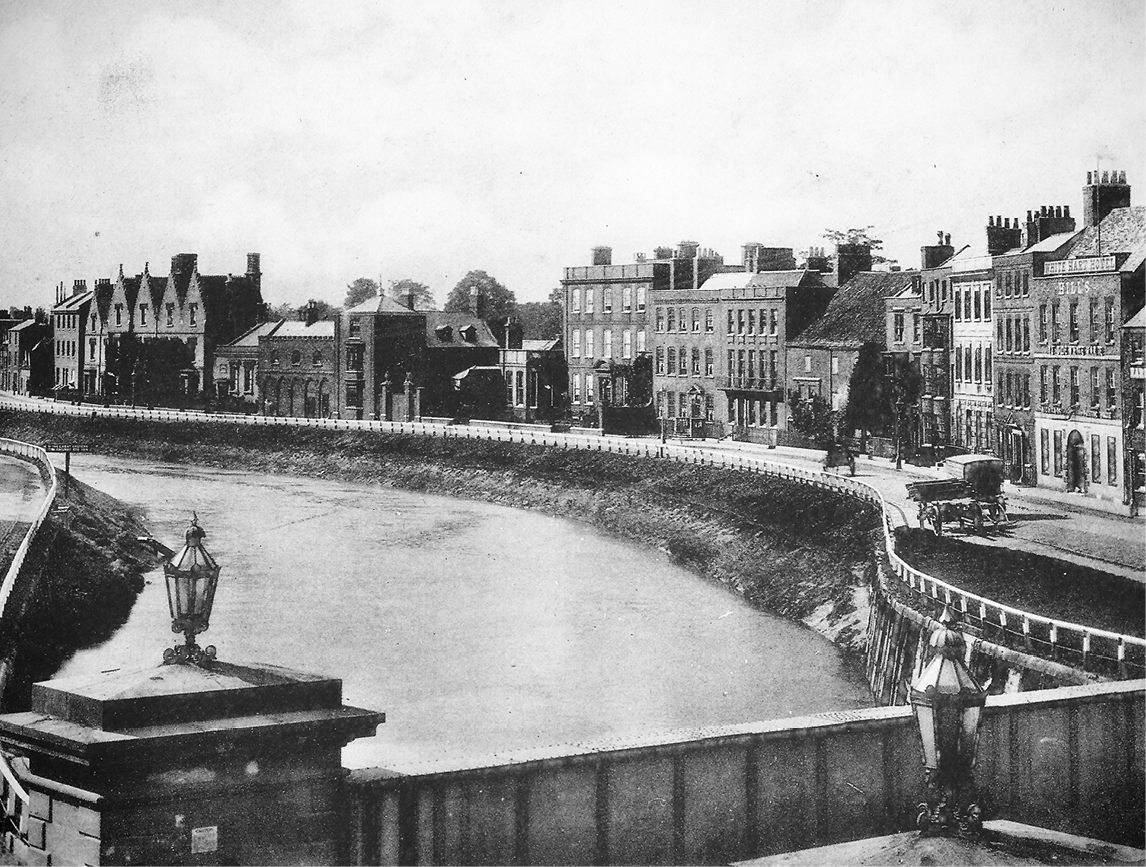

In November 2017 I noticed an obituary in my local paper, the Eastern Daily Press, announcing the death of John Gordon – a 92-year-old Norfolk-based children’s author of whom I was unaware. Jack Gordon, as he was known to his friends and family, was born in Jarrow, Tyne and Wear, in the industrial heartland of England’s north-east, before moving in 1937 as a twelve-year-old outsider to Wisbech, with its antithetical landscape of apple orchards and its boundless fields of sugar beet and potatoes. In his memoir he recalled his Tolly-esque arrival in the Fenland town: ‘A full tide from the Wash had lifted the river’s face to within a foot or two of the roadway and we seemed to be riding through a flood.’ In many regards the place seemed magical to the young Jack, far removed from the abject poverty of post-Depression Jarrow. Later, after a stint in the navy at the end of the Second World War, he returned and became a newspaper reporter for the Isle of Ely and Wisbech Advertiser, where he furthered his knowledge of the town and its surroundings. This familiarity shows in his fiction, in which the unsettling flatness of the landscape is virtually omnipresent. ‘It’s the loneliness and absolute clarity of the line between the land and the sky where you can see for miles that always strikes me with a feeling of magic and mystery,’ he said in a 2009 interview about his last novel, Fen Runners.

The House on the Brink was his second work of fiction, following on two years after 1968’s The Giant Under the Snow, a highly regarded children’s fantasy that centres on the legend of the Green Man. Both were written in Norwich, where Jack had moved in 1962. He wrote his early novels while working on the Evening News, having made the same journalistic journey – junior reporter to sub-editor – that my brother would also go on to make.

I ordered a copy of the out-of-print The House on the Brink from Norwich Library – except for one loan in 2003, its previous excursions from the reserve stores had been in the late seventies and early eighties. This isn’t, it seems, a title in high demand, which strikes me as a real injustice, because Gordon’s second book is a wonderful novel. It does indeed contain strong M. R. James-esque elements within its chapters, drawing most notably on ‘A Warning to the Curious’. But, away from its cautions not to meddle with old secrets – and the arcane forces tasked with making sure any such foolish meddlers are punished – the novel is a world apart from James’s comfort zones. At its core stands a burgeoning first romance between its two protagonists, Dick and Helen, aged sixteen and living in Wisbech (and a nearby marshland village, modelled on Upwell), with a supporting affair between a fragile young widow – the mysterious Mrs Knowles – and her new lover Tom Miller.

M. R. James may well not have found the focus of Gordon’s novel on the emotional interaction of these characters – and the deliberate psychological ambiguity of the uncanny events – to his taste. In ‘Some Remarks on Ghost Stories’ he pointed out what he saw as one of the cardinal errors ruining some modern examples of the genre: ‘They drag in sex too, which is a fatal mistake; sex is tiresome enough in the novels; in a ghost story, or as the backbone of a ghost story, I have no patience with it.’§§

Given that The House on the Brink was published in 1970 and aimed at teenagers there isn’t any sex involved, just a few stolen kisses. But there is a tenderness between the young lovers unlike anything we see in James’s stories. The novel reminds me more of the work of Alan Garner and, in particular, The Owl Service, which has similarly snappy dialogue and a clever, working-class teenage protagonist feeling his way towards a different life. (Indeed, on its release Garner wrote warmly of Gordon’s first book.)

I wish I’d read The House on the Brink as a teenager, as it would have appealed to my then whimsical romanticism and I would’ve identified with the brooding writer-to-be Dick as he biked around the vividly rendered, scorched summer Fens: ‘They went out over the flat land, knowing they dwindled until they were unseen, but still he saw the haze of soft hair on her arms.’ But beyond The House on the Brink’s appreciation of my native landscape and its timeless portrayal of adolescent angst, the novel would have thrilled me with its sense of dread, which threatens at times to overcome its characters. This fixes on a rotting ancient log (which at the story’s denouement reveals its true identity) unearthed from the saltmarsh: ‘The stump was almost black. It lay at an angle, only partly above the mud, and dark weed clung to it like sparse hair. Like hair.’

The teenagers and Mrs Knowles, encouraged by a local wise woman who possesses a feeling for such things (and an ability to divine water that’s shared by Dick and Helen), come to believe that this figure-like fragment of wood is the guardian of King John’s treasure, and has crawled out of the ooze of the marshes to protect its master’s hoard from Tom Miller’s over-curious pursuit. The wooden relic also seems to pre-empt the discovery in late 1998, just around the north-eastern corner of the Wash at Holme-next-the-Sea, of the so-called Seahenge, a Bronze Age circle of timber trunks uncovered beneath the transient sands by the vagaries of the tide.

Jack Gordon infuses an unhinging sense of horror into this stump, on the face of it an unlikely object of terror that seems to offer little threat. Yet the blackened wood’s menace is real, as shown in one of the book’s key scenes where Helen and Dick happen upon it along an overgrown marshland drove: ‘And then, where the hedge clutched the gate-post, half-obscuring it, a round head was leaning from the leaves looking at them.’ What is striking is how much of the action takes place during daylight hours and, given that, how effectively the reader, too, is frightened. Terror does not have to be restricted to the darkness: ‘He let the yell of his lungs hit the black head. Black. Wet. It shone in the sun. And he knew what he should have known before. It had come from the mud.’

Although Wisbech itself, where most of the novel’s action takes place, remains unfamiliar to me, some of its present landmarks are easily recognisable in The House on the Brink. They include the Institute Clock Tower and the Georgian residence of the book’s title, a thinly disguised version of Peckover House, now a National Trust property sited, appropriately enough, on a real (and not just metaphorical) road called North Brink, which runs above the dirty, tidal Nene. The young Jack used to walk for miles along its banks, his younger brother Frank later tells me. The old lighthouse that’s mentioned early on in the book as guarding the saltmarshes at the confluence of the river and the Wash must refer to Peter Scott’s former home – perhaps Jack ended up there on one of his long rambles.

It’s a location that can’t stop itself from appearing in different stories and adaptations, and which, now I think about it, has acted throughout my own life as a strangely unblinking marker that stands on the brink of my vision.