Полная версия:

Map Addict

The A-list map presents all the places that don’t need to be preceded by an apology: the high and mighty locations that know themselves to be the chosen ones. The map of B-list Britain—where I was born, raised and far prefer to live—covers everywhere else. When I’ve written travel features for the national press, it has always been about places that are firmly on the B-list: Birmingham, the Black Country, the East Midlands, Hull, Glasgow, various parts of Wales and Limerick in Ireland. The pattern has been the same every time. I submit my copy, and get a phone call or email a couple of days later suggesting that the feature needs a new introduction; something along the lines of ‘Well, you thought it was all a bit grim and rubbish, but—surprise!—there’s more to Blah than that these days.’ Sometimes they don’t even bother with the phone call or email, just add it as their own introduction, the generic view of B-list Britain as seen from the desk of a London hack. You see it even more graphically in the newspapers’ property pages: it’s cheap, but—oh dear—it’s Humberside.

Every country has its split, its Mason-Dixon Line; the British equivalent was always held to be one that connected the River Severn south of Gloucester with the Wash on the east coast. South of this diagonal lay the comparatively wealthy, Conservative-voting, whitecollar, Church of England part of the land; to the north, the poorer, Labour-voting, manual-working, nonconformist tribes. The line rippled in places, so that the southern tranche extended to Malvern and Worcester, around Warwick and Leamington Spa, and included the hunting country of Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland.

Growing up, it was a border I was acutely aware of, for I crossed it every day on the way to school. It was only a 25-minute train journey from Kidderminster to Worcester, but they were in different worlds. Worcestershire is an England-in-miniature in this regard: the county’s favoured images of orchards, cricket and Elgar belong entirely to its more upholstered, southern half. We in the northern triumvirate of Kidderminster, Bromsgrove and Redditch clung to the coat tails of the West Midlands and felt like scruffy gatecrashers in our own county. It was painfully evident at school, which drew its pupils from right across Worcestershire. The kids from Malvern and the Vale of Evesham had dads in Jags and strutted around the place as if they owned it, which they quite possibly do by now. There was never any doubt that they were several cuts above the far fewer of us who spilled off the train every day from Kidderminster, Stourbridge and Rowley Regis, with accents to prove it.

We even name our goods and companies keeping to the strict rules of the A- and B-list maps. This was something that hit me with a slap years ago in an airless undertaker’s parlour, where my mother and I were trying to sort out the arrangements for my grandfather’s funeral. With that sickly, faux-somnolent air they wear while thinking gleefully of all the noughts on your bill, the undertaker slid the catalogue of available coffins under our noses. They were all called the Windsor, the Oxford, the Canterbury, the Westminster and so on. Where, I wondered, were the Wolverhampton, the Barnsley or the Wisbech? Were Scots offered a Stirling or a Brechin in which to cart away their dearly departed?

A-list names conjure up the solid, dependable image that companies are desperate to tap into. Men’s products, in particular, mine the same seam repeatedly, whether in colognes called Wellington and Marlborough (but not, definitely not, Wellingborough), or the Crockett & Jones range of fine footwear—pick from, among others, Tetbury, Chepstow, Coniston, Brecon, Welbeck, Bedford, Chalfont, Pembroke or Grasmere. We buy insurance from Hastings Direct, rather than Bexhill Direct, where the company’s actually based, and smoke smooth Richmonds, not dog-rough Rotherhithes.

We map addicts are the oddest patriots. Maps bring out a curious British nationalism even in those of us normally allergic to displays of flag-waving. Wherever we go in the world, we pick up a local map and our very first thought is, ‘Hmmm, not as good as an Ordnance Survey.’ We feel sure, we know, that our maps are the finest the world has ever seen. Sneaking in there, too, is the certainty that the landscape they portray is also up there with the very best. We have neither very high mountains, nor very deep ravines nor very wild wildernesses, but the scale—like our climate—is modest and comforting, and the scenery often extremely lovely. And all of it so beautifully mapped.

It’s a force that mystifies me, while still it engulfs me: in absolutely no other aspect of life do I feel so resolutely, determinedly, proudly British. I’ve never voted Conservative (or, God help us, UKIP), bought the Daily Mail, sung ‘Rule Britannia’, stood in a crowd to wave at royalty, watched The Last Night of the Proms with anything other than incredulity or so much as cracked a smile at Last of the Summer Wine. Nearly a decade of living in Welsh-speaking Wales has brought me to the view that the UK as a nation-state might well have had its day, and the sooner we realise it, the better all round. And yet, open up an OS, a Bartholomew, a Collins or even—if nothing else is available—an AA road atlas that cost £2.99 from the all-night garage, and something deep within me trembles. That familiar layout and colouring, those tantalising names and the histories they hint at, the shape of those cherished coasts, the twisting tracks and roads, the juxtaposition of the great conurbations and the wild, empty spaces: a few minutes staring, once again, at the map of this island, or any part of it, and I’m stoked up with a love and a loyalty that knows no reason and no limit.

You have to be careful, though. Not only are there the siren warnings of the pioneers who have gone before, and ended up as wizened, cranky obsessives, but such certainty about British superiority can manifest itself in some pretty strange attitudes, if allowed to seep off the map shelf and into almost any other area of life. Britons are routinely encouraged to cling to the idea that they are, inherently, the best at anything, and if not the best, then at least the most worthy, noble or underrated. And if we can’t be that, we’d rather be the absolute worst: cosmically hopeless, the Eddie the Eagle among nations, usually coupled with a graceless sneer when we lose: ‘Pfft, well, we never wanted it, anyway.’ Rarely are we either the best or the worst, but it’s our actual position of mid-table mediocrity that we struggle hardest to cope with.

Though not when it comes to our maps: even Johnny Foreigner grudgingly admits that we’re still world-beaters in cartography. There is no other patch of land on the planet that has been as comprehensively, and so stylishly, measured, surveyed, plotted and mapped as the 80,823 square miles of Great Britain. We might have been late starters in the game, but we’ve more than made up for it subsequently, especially over the past four hundred years—ever since, in fact, we started needing maps in order to go and rough up bits of the rest of the world and declare them to be ours. Again, this is the perverse dichotomy of the British map aficionado: were it not for the Empire and our military bravado, we would be a great deal further down the cartographic rankings. It’s a dilemma to wrestle with, for sure, but boy, are we grateful for the maps.

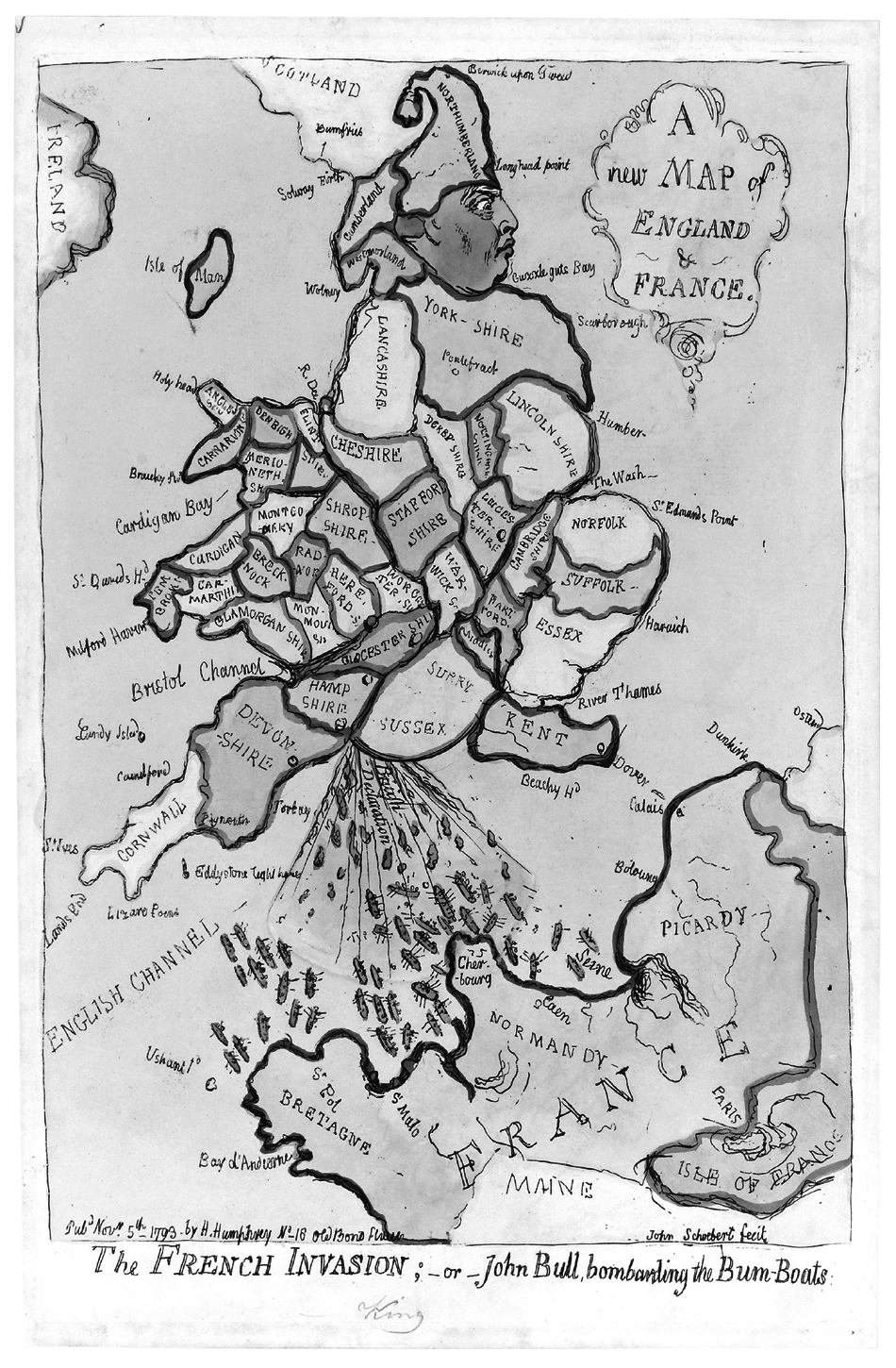

James Gillray’s map of England as King George III, crapping ‘bum boats’ into France’s mouth

2. L’ENTENTE CARTIALE

We always have been, we are, and I hope that we always shall be, detested in France.

˜ The Duke of Wellington

That our cartography is transparently the best in the world is the battle cry of every British map addict. We wave our OS Landrangers in the same spirit that the English longbowmen at Crécy flourished their state-of-the-art weaponry at the French, confident that we are holding the latest, the most accurate, the loveliest maps known to man. And one single fact underpins this whole fabrication, the slender basis for our patriotic fantasy. We must have mapped the world better than anyone, because every measurement, in all its precision, and the whole grid on which every map depends are taken from a base that passes through—and is named after—an otherwise unremarkable suburb of London. Greenwich Mean Time, and the Greenwich Meridian, the world’s cartographic backbone, is ours.

And we don’t have to put our country’s name on our stamps. Same principle. We were first, therefore we were the best and got special privileges.

Take that République Française, with your overly wordy timbrespostes and your redundant meridian, left abandoned and overgrown like a Norfolk branch line closed in the 1960s. And take that USA, for that matter. You may have superseded us in just about every possible aspect of superpower status, but we’ve still got the maps, the clocks and the meridian. It’s a small victory, granted, but it’ll have to do.

To a junior map addict, who gazes at a British map with the fondness of Rod Stewart at a brand new blonde, the certainty that our maps are so good is buried deep within and breaks out in pustules of xenophobic acne. In the 1970s, watching the TV news, I was genuinely and repeatedly surprised to see how developed the rest of the world seemed to be when it flashed past on a nightly basis. Surely, these places couldn’t be as sophisticated as the Land of Hope, Glory and the Ordnance Survey? When, at the age of six, I first visited my mother after she’d moved to France, I couldn’t quite believe that Paris had traffic lights, zebra crossings, decent shops, well-dressed people—people even fully dressed at all. It was Not England; therefore it was supposed to be dusty and primitive. It looked—whisper it quietly—just like home. Only—whisper it even more quietly—rather better.

Ah, la belle France. Our nearest neighbour, archest rival, flirtiest paramour, oldest, bestest friend and bitterest foe, all rolled into one. We and the French are like an ancient, brackish couple locked into what looks from the outside like the stalest of wedlock, but which, behind firmly locked doors, is as doe-eyed as a Charles Aznavour chorus. We sneer at them, but around eleven million of us make our way over the Channel every year to wallow in their wine, cheese and meats of dubious provenance. They sneer at us, but can’t get enough of our culture, either high, in the ample shape of royalty and aristocracy, or low, from punk to getting pissed properly. We look down on them for their pomposity, their flagrantly over-inflated sense of their own importance, their rudeness, their insularity, their ponderous bureaucracy, their clinging to a long-vanished past, their dodgy new best friends, their fiercely centripetal politics, their all-round unwarranted, swaggering arrogance. They look down on us for precisely the same reasons.

It is this intense neighbourly rivalry between Britain and France that has driven most of the advances in mapping over the past four hundred years—or, more specifically, it is the ever-watchful competitiveness between their two capital cities, London and Paris. These citystates in all but name have been peering haughtily at each other across that slender ribbon of water for the past two thousand years. Both are convinced that they are the epitome of all that is civilised and progressive in this world, and both have so much in common—not least their terribly high opinion of themselves.

It’s a rivalry that endures, even constantly reinvents itself, like a family feud that passes down the generations long, long after the original protagonists are cold in the sod. Some of the finest mapping of its age was the by-product, such as the forensically detailed eighteenth-century invasion plans that each side drew up of the other’s nearest coastline during that hundred years or more of semi-permanent war that existed between the two nations until the 1815 full stop—or rather, semicolon—of the Battle of Waterloo. As the nineteenth century progressed, the arena for mutual Anglo-French antagonism was widened, each side having already flexed its muscles in competing for territories in north America. Now, no part of the globe was immune from the colonisers, with each side racing to capture—and, for the first time, map—lands in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and the Caribbean. The tectonic plates of power were shifting in Europe too, and lavish maps, often with home territories boldly exaggerated or shown as definite possessions when they were little more than statements of ambition, were produced by British and French cartographers in each nation’s struggle to be perceived as the continent’s top dog. France and Britain took the idea of the map as one of the boldest, and most swiftly absorbed, tools of political indoctrination and launched it into the modern era.

Even in today’s much reduced times, the snippiness between London and Paris continues to fuel outbreaks of hubristic condescension on both sides, wind-assisted by maps. Londoners will glower over the maps, drawn up by London County Council, of sobering Second World War bomb-damage, showing the city utterly blitzed and razed in hard-won victory, and could be forgiven for comparing them with their Parisian equivalents, depicting only the lightest of grazes to the city’s elegant face, thanks to its people’s early capitulation to the losing side. Parisians in the 1980s and ’90s loved to brandish their metro map in the faces of any passing Brits, showing as it did the splendid new RER (Réseau Express Régional) lines that scorched across the city like high-velocity darts, while muttering darkly about their last visit to London and memories of chaos on the Northern and Central Lines. And how fitting was it that, once the extravagant French plans and maps had been compared with the more down-to-earth British ones, London squeaked its victory to host the 2012 Olympics over Paris, the long-time front runner and bookies’ favourite?

When it comes to comparing the current standard of our respective national maps, it’s a shockingly one-sided contest, and I’m really trying to be impartial. The French equivalent of the Ordnance Survey is the Institut Géographique National (IGN), and its maps are awful. Leaden, lumpy, flimsy and downright ugly, they are often hard to find, and not worth the bother of trying. The 1:25 000 series, the equivalent of the OS Explorer maps, is an assault on the eyes, with its harsh colours, grim typefaces and lousy printing; they look plain cheap and you’d be hard pressed to work out a decent walk from any of them. The 1:50 000 orange series, the equivalent of our OS Landrangers, with the same problems of garish colours and typographic overcrowding, somehow manages to be even worse. France is larger than Britain, granted, about two and a half times the size, but they’ve carved up the country so ineptly that you’d have to buy 1,146 of these dreadful maps, at a cost of nearly €10,000, to cover the whole country—nearly six times the number of OS Landrangers (204, costing less than £1,500), which would get you the whole of Britain at exactly the same scale and in far greater style. IGN maps at 1:100 000 are not quite as bad, but really, at any scale, you’d be better off in France with the Michelin series, for they are always far more elegant than the government jobs. But still nowhere near as good as You-Know-Who.

At least there’s one area of life where you can always rely on the French, and that’s managing to squeeze a bit of soft porn into the most unlikely topic, even cartography. Back in those innocent pre-internet days, when you had to rely on a late BBC2 or Channel 4 film for a glimpse of flesh, I remember catching one night an early 1970s movie by the name of La Vallée. In English, it was called Obscured by Clouds, after the intriguing caption written over a huge blank space on the map of Papua New Guinea. This, they stated in the film, was an unknown mountainous region, the last place on Earth that had yet to be mapped. A gorgeous young French consul’s wife, Viviane, is in the country to find exotic feathers for export to Paris; she joins an expedition into the unmapped mountains, which soon turns into a phantasmagoria of mind-expanding substances, writhing bodies and an accompanying soundtrack by Pink Floyd. Even at the age of seventeen, I found the idea of the map a far bigger turn-on than a few soft-focus French hippies in the buff.

When it comes to mapping Paris, the ‘us versus them’ contest is a little more equal. Despite endless redesigns, they’ve never managed a metro map with quite the same panache and clarity of the equivalent one of the London Underground. Even when they tried to mimic Harry Beck’s design directly, the result was the proverbial dîner du chien and it was quickly scrapped. With the street maps of the city, however, the French have long since hit on a winner. While the London A-Z and its myriad of near equivalents do the job with postman-whistling efficiency, the little red book that can be found in the handbag of any Parisian (except perhaps for the ones that house small dogs) combine utility with élan. Considering how much the French love to make of their superior sense of style, it’s just as well they’ve got at least one map to prove it.

The little red book—by Cartes Taride, Éditions André Leconte and others—fits Paris perfectly: it’s lightly stylish, full of fascinating detail, slightly bewildering and extremely easy just to lose yourself in. Its art deco titling on the cover, like the classic Métropolitain signs, and its format have been pretty constant since the end of the nineteenth century. The main mapping—colourful, cheerful and crowded—is done arrondissement by arrondissement, with the spill over of the suburbs to follow. There are fine fold-out maps of the metro and the RER, but the fun is only just beginning. Every street in the index—which has those handy A-Z dividers you find in address books—is given its nearest metro station, every bus route is represented by a scaled-down version of the classy linear map that you find on board the bus, with every stop clearly marked, and there are map references, addresses, phone numbers and nearest metro stations given for every police and fire station, government office, embassy, hospital, monument, museum, cinema, theatre, cabaret, railway terminus, place of worship and even cemetery. All contained within something measuring just three and half by five and a half inches.

I may well be biased, for the Paris street atlas is something I’ve known intimately and loved unconditionally for over thirty-five years, ever since my mum moved there. Although it was no fun being the first in class to have his parents divorce, there were definite benefits, regular trips to Paris being a pretty obvious one, especially when the other parent is in a Midlands town that can only be called a capital within the very tight confines of carpet manufacturing. The first time my sister and I went over there to visit Mum, I was terrified; convinced that the law in France demanded that everyone speak French all the time, and that I wouldn’t be able to say a word to her, nor understand anything she said to me. Mum would let me go off to get breakfast from the local boulangerie, sending me out with a ten-franc note and the phrase une baguette et trois croissants, s’il vous plaît drilled into my brain. On the second visit, I’d walk a little further to another boulangerie, then a little further still, until, by the time I was about nine, I’d hotfoot it into the nearest metro station (Porte de Champerret, ligne 3), ride a train or two and collect some bread from whichever random part of the city I surfaced in. Fortunately, my mum and my sister weren’t averse to having breakfast at about eleven o’clock.

My hunter-gathering for bread was beyond excitement: armed with my little red book, I felt such an integral part of this sophisticated city, a tiny corpuscle pelting through the arteries of this statuesque grande dame. It was an intoxicating buzz, one which encapsulated so many of the things that I’ve most come to value: freedom, travel, spontaneity, humanity. For I never felt in any danger—quite the opposite, people couldn’t have done more to help. I was reminded of those happy days when, in April 2008, ‘America’s Worst Mom’ (as she was dubbed by Fox News and the shock-jocks), a newspaper columnist, wrote about letting her nine-year-old son ride the New York subway on his own. America divided down the middle, many cheering her for taking on the media-fuelled paranoia of modern parenthood. They didn’t generate quite as much noise, however, as the half of the country who screamed cyber-abuse at her from within their fortress compounds, while their inert, incarcerated children fantasised about the day they’d go beserk in a shopping mall with a handgun. What about the murderers, they ranted, the muggers, the paedophiles, the gropers, the platform-shovers, the terrorists lurking round every corner? Are you out of your mind, lady? But have they been to New York lately? You’re more at risk walking through Ashby-de-la-Zouch on a Saturday night.

So many years of getting to know Paris made me support her instinctively in the eternal duel with London. Our capital seemed angry and chaotic by contrast, a sensation that only deepened when I lived there for four years at the end of the 1980s, initially at university and then trying to commute every day right across the city for my first job. London during that period was a mess: the glistening towers of Docklands rising fast out of the debris around them, a glassy two fingers to the squalor and poverty, the doorway-sleepers and the disenfranchised. It suited me well, though. Being angry and chaotic myself, London couldn’t have matched me more perfectly. From the lofty heights of my college in leafy Hampstead, I joined every campaign, protest and march, finding myself applauding Tony Benn most weekends at some rally or other in Trafalgar Square. What do we want? Er, student grants, no poll tax, freedom for Nicaragua, Nelson Mandela, Thatcher’s head on a pole…what was it this time? When do we want it? NOW! Two days before the dawn of the 1990s, I left London, smug and thankful that I was quitting this seething metropolis for a return to the safety of the Midlands. Paris was still on its elegant little pedestal in my mind, and I ranted at anyone who’d listen about its vast superiority, and that of France as a whole, over our mean-spirited little Tory island and its yuppie capital. Gradually, though, I fell in love with London all over again, seduced by its energy, its caprice, its sheer balls. One up, one down: the lustre of Paris was peeling, its Mitterand era chutzpah shrivelled into a matronly conservatism.

So many of the advances in cartography, as well as practically every other discipline, have stemmed from the ancient grudge and eternal competitiveness between these two great cities; it is a theme that reappears as the steadiest leitmotif through any analysis of modern maps and mapping. The victory in securing the world’s prime meridian for Greenwich was perhaps our literal high noon in the battle, which came at the 1884 International Meridian Conference in Washington, DC. Delegates from twenty-five nations gathered from the first of October, charged with finally settling the question that was dogging the world’s governments, and its transport and export industries.

Up until then, anyone anywhere could, and did, work to their own meridian. While the Equator is a fixed line of latitude—determined by its position at the centre of an oblate (i.e. polar-flattened) spheroid, its particular climate and the fact that its days and nights are of equal length the whole year round—the defining line of longitude, namely a full circle around the globe that connects the two poles vertically, can be placed anywhere. Establishing longitude was essential for navigation, especially at sea, but also for working out relative time zones. When the sun is overhead at noon in one place, 15° (i.e. 1/24 of 360°) west or east it is an hour different. Time was delineated in what might be called the way of the sundial, so that it was noon in any particular place when the sun was highest in the sky. Even in a country as tiny as Britain, this meant that there were numerous different local times in operation. With the advent of the railways, this had to change on a national basis, and soon, thanks to the massive upsurge in oceangoing trade, the need to standardise time zones between countries became acute, especially as there was a plethora of meridian lines being used by different countries.