Полная версия

Полная версияLife and Lillian Gish

Uncomplainingly, but what must have been going on inside. There was a small studio in New Rochelle, the Fischer studio. It was a poor thing, but at least there were lights. The Mamaroneck electric people promised that if she would work there a few days, everything would be all right when she got back. So they carted themselves and their sets to New Rochelle, and began again.

“It was certainly a poor place,” Lillian remembered; “Damp, the cellar full of water, no heat, and being late November and into December, it was very cold. Often, the actors had to hold their breath so it wouldn’t photograph. The next Sunday we all moved back to Mamaroneck. The lights, they told us, were all right, but that was a mistake. Back we went to the Fischer studio. In all, we moved back and forth three times. I very nearly lost my mind.

“Of course, I was responsible, and spending money—oh, by the thousands. Mr. Epping, our business manager, every night brought me the items of what we had spent that day. I am not much at figures, but I could read the total, which was not cheerful. But everybody stood by me, the ‘boys,’ as we then called the electricians and property men, especially. The actors, too—everybody.

“The last day’s work had to be done on Fifth Avenue, New York. It happened to come on the day before Christmas, and I didn’t want to postpone it. We engaged a bus, from which Dorothy had to look down and see her ‘husband’ ride by in a cab with another woman. To work on the street without a permit laid us open to arrest and fine, with a good chance of spending Christmas in jail. To get a permit would take time, which we could not afford. ‘Will you take a chance?’ I asked those who were going to do the scene. They agreed that they would, but things had a dubious look.

“Nevertheless, we got our bus and our taxicab, and started. I was on the bus with the camera-man—George Hill, now a famous director—Dorothy at the other end, the taxi just below. We had not gone a block when an enormous policeman started over, to see what it was all about. Then he took a good look at me and stopped, placed his fingers at the corners of his mouth and ‘put up’ a smile.

“You remember the scene in ‘Broken Blossoms,’ where the brutal father commands his terrified daughter to smile. I knew right away the big policeman had seen it. He really smiled, then, and so did I. ‘Oh, it’s you, is it?’ he said. ‘Yes, and this is my sister, Dorothy, and we’re trying to finish a picture before Christmas.’ ‘Go right on,’ he said. Farther up the Avenue, another policeman called out: ‘What do you think you’re doing up there?’ I put up the smile myself, that time, hoping he had seen the picture. Evidently he had, for he laughed and waved us along. I thought it safer not to break any new ground, so we turned and made the circuit. We made it several times, and were not troubled again, but helped.

“That night we knew we were done, and everybody was so happy, and so sorry, weeping on one another’s shoulders. By the time Mr. Griffith came home, our picture was nearly all cut, and ready. When he saw and approved of it, I was very happy, but it had nearly killed me.”

Lillian decided that directing was not for women. “Remodeling a Husband,” as the picture was finally called, turned out a financial success. She had spent fifty-eight thousand dollars, and twenty-eight days, making it, but it netted a profit of a hundred and sixty thousand dollars, and doubled Dorothy’s picture value. She was proud of all that, but did not care to try it again. A little while ago David Wark Griffith said:

“Lillian directed Dorothy in the best picture Dorothy ever made. I knew she could do it, for whenever we were making a picture I realized that she knew as much about it as I did—gave me valuable ideas about lights, angles, color, and a hundred things. She had brains, and used them, and she did not lose her head. You see what confidence I had in her to go off to Florida and leave her to direct a picture in a new studio, with all the problems of lights and sets, and a thousand other things a director has to contend with. I know how her lights failed on her, and all the complications that came up, and how she handled them, and how, out of it, she got that fine picture. One of the best. She didn’t tell me, but Carr did.”

XVII

“WAY DOWN EAST”

Griffith now began work on his greatest melodrama. “Way Down East” had been successful as a book and a play, and was precisely the sort of thing he could do best. From William A. Brady, for a large sum, he secured the picture rights, and plunged into production. There were to be two great outdoor scenes: a blizzard, in which the heroine, who has been inveigled into a mock marriage—and is, therefore, under the New England code, fallen and outcast—is lost; and the frozen river, which, blinded and desperate, she reaches, to be carried to the falls on a cake of ice. There was very little that was artificial about such scenes, in that day: the blizzard had to be a real one, the ice, real ice—most of it, at any rate. Griffith began rehearsing some scenes at Claridge’s Hotel, in New York, continuing steadily for eight weeks; but all the time there was an order that in case of a blizzard, night or day, all hands were to report at the Mamaroneck studio. Lillian had taken Stanford White’s house on Orienta Point. Reading the play, she knew it was going to be an endurance test, and went into training for it. Cold baths, walks in the cold against the wind, exercises … she had faith in her body being equal to any emergency, if prepared for it. In a magazine article, a few years later, she wrote:

The memorable day of March 6th arrived, and with it a snow-storm and a ninety-mile-an-hour gale. As I was living at Mamaroneck, near the studio, I quickly reported, and was made up as Anna Moore, ready but not eager for the work to be done. The scene to be taken was the one just after the irate Squire Bartlett turns Anna out of the house into the storm. Dazed and all but frozen, she wanders about through the snow, and finally to the river.

The Griffith studio was on a point or arm well out in Long Island Sound. The wind swept this narrow strip with great fury. The cameras had their backs to the gale. She had to face it.

She had been out only a short time when her face became caked with snow. Around her eyes this would melt—her lashes became small icicles. Griffith wanted this, and brought the cameras up close. Her lids were so heavy she could scarcely keep them open.

No need of spectacular “falls.” The difficulty was to keep her feet. She was beaten back, flung about like a toy. Her face became drawn and twisted, almost out of human semblance. When she could stand no more, and was half-unconscious, they would pull her back to the studio on a little sled and give her hot tea. A brief rest and back to the gale. Griffith had invested a large sum in the picture, and she must make good. One could not count on another blizzard that season. Harry Carr writes:

That blizzard scene in “Way Down East” was real. It was taken in the most God-awful blizzard I ever saw. Three men lay flat to hold the legs of each camera. I went out four times, in order to be a hero, but sneaked back suffocated and half dead. Lillian stuck out there in front of the cameras. D. W. would ask her if she could stand it, and she would nod. The icicles hung from her lashes, and her face was blue. When the last shot was made, they had to carry her to the studio.

A week or two later, they were at White River Junction. Vermont, for the ice scenes. Griffith took a good many of his company, and they put up at an old-fashioned hotel, a place of hospitality and good food.

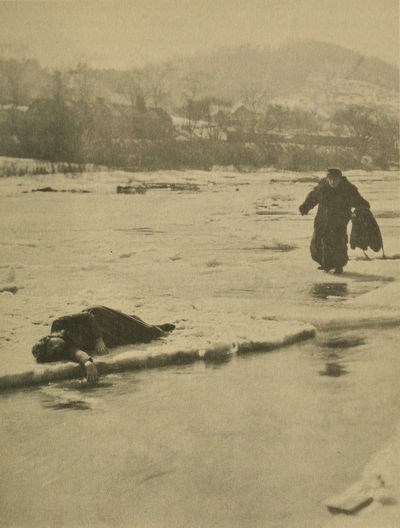

White River Junction is at the confluence of the White and the Connecticut rivers. There is no fall there, but the current moves at the rate of six miles an hour, and the water is deep. The ice was from twelve to sixteen inches thick, and a good-sized piece of it made a fairly safe craft, but it was wet and slippery, and very cold. It was frozen solid when they arrived; had to be sawed and dynamited, to get pieces for the floating scene. Lillian conceived the idea of letting her hand and hair drag in the water. It was effective, but her hand became frosted; the chances of pneumonia increased. To the writer, recently, Richard Barthelmess, who had the star part opposite Lillian, said:

“Not once, but twenty times a day, for two weeks, Lillian floated down on a cake of ice, and I made my way to her, stepping from one cake to another, to rescue her. I had on a heavy fur coat, and if I had slipped, or if one of the cakes had cracked and let me through, my chances would not have been good. As for Lillian, why she did not get pneumonia, I still can’t understand. She has a wonderful constitution. Before we started, Griffith had us insured against accident, and sickness. Lillian, frail as she looked, was the only one of the company who passed one hundred percent perfect—condition and health.

“No accidents happened: The story that I missed a signal and did not reach Lillian in time, and that she came near going over the falls, would indicate that she made the float on the ice-cake but once. As I say, she made it numberless times, and there were no falls. Lillian was never nervous, and never afraid. I don’t think either of us thought of anything serious happening, though when I was carrying her, stepping from one ice-cake to another, we might easily have slipped in. I would not make that picture again for any money that a producer would be willing to pay for it.”

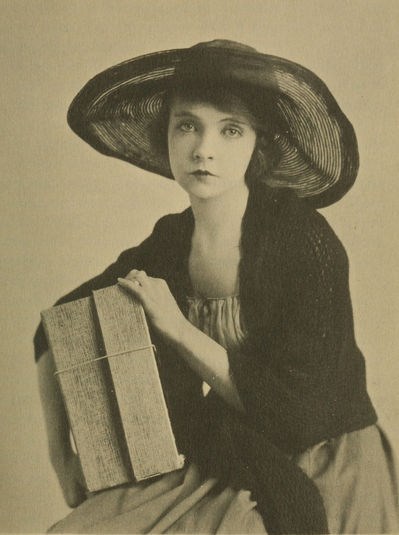

“ANNA MOORE”

At the end of the ice scene, there is an instant when the cake, at the brink of a fall, seems to start over, just as Barthelmess, carrying Lillian, steps from it to another, and another, half slipping in before he reaches the bank.

The critical moment at the brink of the fall was made in summer-time, at Winchell Smith’s farm, near Farmington, Connecticut. The ice-cakes here were painted blocks of wood, or boxes, and were attached to piano wire. There was a real fall of fifteen feet at this place, and once, a carpenter went over and was considerably damaged. In the picture, as shown, Niagara was blended into this fall, with startling effect.

Barthelmess remembers that Lillian kept mostly to herself. She took her work very seriously—too much so, in the opinion of her associates. But once there was a barn-dance at the hotel, in which she joined; and once she and Barthelmess drove over to Dartmouth College, not far distant, with Mr. and Mrs. Elmer Clifton, to a dinner given them by Barthelmess’s fraternity. After dinner, they heard a great tramp, tramp, and someone said to Lillian: “It’s the college boys, coming to kidnap you.” They sometimes did such things, for a lark.

But they only wanted to pay their respects. They gathered outside the window, which Mr. Clifton opened, and both Lillian and Barthelmess spoke to them through it.

The summer scenes of “Way Down East” were made at Farmington and at the Mamaroneck studio. Griffith had selected a fine cast, among them Lowell Sherman, the villain; Burr McIntosh, as Squire Bartlett; Kate Bruce, his wife; Mary Hay, their niece; and Vivia Ogden, the village gossip. The scene where Squire Bartlett drives Anna Moore from his home, was realistic in its harshness, and poor Burr McIntosh, a sweet soul who long before had played Taffy in “Trilby,” and who loved Lillian dearly, could never get over having been obliged to turn her out into the storm. Often, in after years, he begged her to forgive him.

A few minor incidents, connected with the making of “Way Down East,” may be recalled: Griffith had spent a great sum of money for the rights—$275,000, it is said—and was spending a great many more thousands producing it. He was naturally on a good deal of a tension. All were working to the limit of their strength, but they could not hold the pitch indefinitely. When Barthelmess, who is short, had to stand on a two-inch piece of board, to cope on terms of equality with Lowell Sherman, Sherman, who was a trained actor of the stage, could, and did, make invisible side remarks which made Barthelmess laugh. Whereupon, Griffith raged at the waste of time and film, and everybody was sorry, the villain penitent. “Stop that laughing! Turn around and face the camera,” were sharp admonitions perpetuated by a right-about-face in the picture to this day.

It was harsh in form, rather than by intention. They did not resent these scoldings. They believed in Griffith, knew something of his problems, wanted him to make good.

There was one scene during which Griffith had no word to offer—the scene in which Anna Moore (Lillian) baptizes her dying child. Harry Carr writes:

The only time I ever saw a stage-hand cry was in the baptism scene in “Way Down East.” It was made in a boxed-off corner, with only D. W., Lillian, the camera-man, a stage-hand and myself there. Everybody cried. It never made the same impression on the screen, because it was necessary to interrupt the action with the sub-titles. You saw her dripping the water on the baby’s head; then a sub-title flashed on, saying: “In the Name of the Father, etc.,” and the spell was broken.

Carr, Lillian and Griffith would sit far into the night, watching rushes from the scenes made the day before. It was a drowsy occupation—so many of the same thing—and after a day in the open, it was not surprising that Carr should nod. Across a misty plain of sleep, Griffith’s voice would come to him: “Which shot do you like best, Carr?”

It is noticeable in the baptism scene, that Lillian sits relaxed, her knees apart; that when she leaves the house, she walks with a dragging step, as one who had recently experienced the struggle and agonies of child-birth. It has been suggested that she had visited a maternity hospital for these details. When asked, she said:

“No, I did not do that. There was an old woman connected with the studio, who had borne a number of children. She told me all that I needed to know. I learned something, too, from pictures of the Madonna, by old masters. I noticed in all of them that the Madonna sat with her knees apart. I felt that there must be a good reason for painting her in that way.”

She had studied out every detail of the scenes she was to play. Many actors, even among the best, work by another method. They absorb the feeling of the plot, fling themselves into a scene, depending upon an angel to kindle the divine fire. This method never was Lillian’s. To her, the bush never of itself became a burning bush. She lit the fire and tended it. She knew the effect she wanted to produce, and found no research too tedious, no rehearsal too long—no effort too great, to achieve her end.

“Way Down East” was shown in October. Griffith, with Lillian and Barthelmess, were present in person, in the larger cities. It was like a triumphal tour. To present the “world’s darling” in scenes of actual danger, on the screen, and then have her appear in person, was to invite something in the nature of a riot. Reporters indulged in the most extravagant language. And there was a freshet of poetry, and of letters—love-letters, many of them, but letters, also, from persons distinctly worthwhile. David Belasco, whose “most beautiful blonde” verdict had long since gone into the discard, démodé, wrote:

Dear Lillian Gish,

It was a revelation to see the little girl who was with me only a few years ago, moving through the pictured version of “Way Down East” with such perfect acting. In this play, you reach the very highest point in action, charm and delightful expression. It made me happy, too, to see how you and your name appeal to the public.

Congratulations on a splendid piece of work, and good wishes for your continued success.

Faithfully,

David Belasco

John Barrymore went even further, when he wrote:

My dear Mr. Griffith:

I have for the second time seen your picture of “Way Down East.” Any personal praise of yourself or your genius regarding the picture I would naturally consider redundant and a little like carrying coals to Newcastle....

I have not the honor of knowing Miss Gish personally and I am afraid that any expression of feeling addressed to her she might consider impertinent. I merely wish to tell you that her performance seems to me to be the most superlatively exquisite and poignantly enchaining thing that I have ever seen in my life.

I remember seeing Duse in this country many years ago, when I imagine she must have been at the height of her powers—also Madame Bernhardt—and for sheer technical brilliancy and great emotional projection, done with an almost uncanny simplicity and sincerity of method, it is great fun and a great stimulant to see an American artist equal, if not surpass, the finest traditions of the theatre.

I wonder if you would be good enough to thank Miss Gish from all of us who are trying to do the best we know how in the theatre.

Believe me,

Yours very sincerely,

John Barrymore

Mrs. Gish, who was not a motion-picture enthusiast, made a single comment:

“Well, young lady,” she said, “you’ve set quite a high mark for yourself. How are you going to live up to it?”

THE RIVER SCENE IN “WAY DOWN EAST”

“Way Down East” was one of the most popular and profitable pictures ever made. Net returns from it ran into the millions. It has had several revivals, and at the present writing (Winter, 1931), is being shown at the Cameo Theatre, New York, “with sound.” Its day, however, is over. Taste has changed—has become what an older generation might regard as unduly sophisticated, depraved. This, with mechanical advancement—the talking feature, for instance—tells the story. A picture of even ten years ago—five years ago—is without a public.

“Way Down East” is a melodrama, but one that at moments rises to considerable heights. Putting aside the spectacular features of the picture—the blizzard and the ice-drift, where melodrama is raised to the nth degree—the scene where the villain reveals to his victim that their marriage was a mockery, the scene where Anna Moore, about to be turned out into the storm, denounces her betrayer, and the baptismal scene, already mentioned, are drama, and, as Lillian Gish gave them, worthy.

And, after all, what is, and is not, melodrama—and cheap. Cheap—because it is human. That is why we have invented for ourselves a hereafter—a place away from it all—of rest by green fields and running brooks. Very well, let us agree that the play was cheap, especially the comedy, which was low comedy and about the record in that direction. But if Lillian’s acting was cheap, and poor, then there is very little to be said for any acting, which, God knows, may be true enough, after all!

XVIII

SAD, UNPROFITABLE DAYS

Lillian to Nell, June 30, 1920:

Do you know that I am leaving Mr. Griffith? “Way Down East” that we are on, will be my last. I go with the Frohman Amusement Company, between the 1st and 15th of August. I am to make five pictures a year, for two years. If I make successful pictures, I shall make a lot of money. If I don’t, well, kismet—it’s all a gamble, anyway.

It was more of a “gamble” than she knew. Strictly speaking, there was no such thing as the “Frohman Amusement Company.” No Frohman—no amusement Frohman—had anything to do with it. That was just a part of the gamble. Griffith, apparently, thought it all right, and so did his brother, for it was the latter who made the connection. Had Lillian made inquiries on her own account, her eyes might have been opened sooner, and less expensively.

Griffith and Lillian parted on the friendliest terms. Griffith said to her:

“You know the business as well as I do. You should be making more money than you can make with me.” He did not say: “Stay with me and share in the prosperity which you have brought, and will bring me. No one can be more successful than we two together.” To a simple-minded literary person, this would seem to have been the wisest course. Lillian thinks he had perhaps grown tired of seeing her around.

She did not make five pictures for the Frohman company, or even one. She did begin one, “World’s Shadows,” by Madame de Grésac, who claims here a word of introduction:

Somewhat earlier, Lillian had met this gifted French lady, god-daughter of Victorien Sardou, wife of the singer, Victor Maurel, herself a dramatist who had written French, English and Italian plays for Réjane, Duse, Marie Tempest, and others of distinction. Familiar with the best literary and art circles of Paris, considerably older than Lillian, small, red-haired, quick of speech—French, in the best meaning of the term—she was a revelation to the younger woman, who in spite of her years on the stage and screen, was a good deal of a primitive as to world knowledge, and art in its less obvious forms. The two were mutually fascinated: Madame de Grésac, dazed and delighted by Lillian’s gifts and innocence; Lillian, stirred and awakened, and sometimes shocked, by the French-woman’s brilliant mentality, her knowledge of life, her freedom of expression. In a brief time, they were devoted friends, confidantes.

When the so-called Frohman company wanted a picture for Lillian, Madame de Grésac agreed to prepare one. She did so, but about the time rehearsal was under way, Lillian’s first (and only) salary cheque from the company was returned from the bank, unpaid—“No funds.” They explained to her that certain backers had disappointed them. It may be so. At all events, there was a hitch somewhere, in this particular gamble. Lillian carried on, as a number of players had come with her from the Griffith staff, and as they seemed to be getting their money, she could not leave them in the lurch. But, of course, the end came. Their pay, also, stopped. The thing that had never really existed, ceased to function. It was all a fiasco—a tragedy … so many tragedies in the show business.

“World Shadows” was discarded. It made no difference between the two friends. If anything, they were closer than before. The day was coming, not so many years ahead, when they would combine in another play—a success.

Madame’s husband, Victor Maurel, besides being a singer, had a passion for painting, and persuaded Lillian to pose for him. Lillian, with a view of sometime going back to the stage, greatly desired voice culture. They agreed that in exchange for half an hour’s posing, he would devote half an hour to training her voice. She had then finished “Way Down East,” which Maurel seemed to love. He watched it, time and again; then he had her go into a separate room, a dark room, and convey the feeling of it—paint the picture, as it were, with her voice. This was priceless training. It gave her voice a quality and value it had not possessed before. “From Maurel,” she said afterwards, “I got my consonants.”

Except for the triumph of “Way Down East,” a triumph not easy to understand in this more crowded, more inattentive day, that year of 1920 was hardly a cheerful one. For one thing, Mrs. Gish was in poor health. Dorothy had taken her to Italy, which might have been well enough but for the circumstances of their return.

It was the tragedy of Bobby Harron that brought them back. On September first, alone in his hotel room, Bobby shot himself. For years, he had been as one of the family. From the days of the Biograph company, he had taken part in pictures with both Lillian and Dorothy; he had shared the hardships and dangers of those days and nights of bomb and shrapnel, in London and France. He had been a brother to them—to Dorothy, for a time, at least, something more. Now, he was dead.

Exactly what happened will always be a mystery. Lillian, in Philadelphia, where they were opening “Way Down East,” wrote Nell:

These have been terrible days—the worst I have ever known. You have heard about it by this time, I imagine—about Bob: He was in his room, unpacking an old trunk, when a pistol fell out and exploded, the ball going through his lung. That was Sept, 1st, at 10:30 in the morning. He was taken to Bellevue, where he seemed to improve—we all held such high hopes—until Sunday morning, at 7:55, he breathed his last. Mother and Dorothy were some place in Italy—could get no word to them until Wednesday. They are taking the first boat home, which leaves today.