Полная версия

Полная версияRoyal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

There would seem to have been a little pause of calm and comfort in James's life after this victorious expedition. Clouds already bigger than a man's hand were forming on his horizon; the country had begun to be agitated throughout its depths with the rising forces of the reform, and the priests who had always surrounded James were hurrying on in the truculence of terror to sterner and sterner enactments against heretics: while he, probably even yet but moderately interested, thinking of other things, and though adding to the new laws which he was persuaded to originate in this sense, conditions to the effect that corresponding reforms were to be wrought in the behaviour of the priesthood,—had not entered at all into the fierce current of theological strife. He followed the faith in which he had been bred, revolted rather than attracted by the proceedings and pretensions of his uncle of England, willing that the bishops, who probably knew best, and who were, as he complained to the English ambassador, the only men of sense and ability near him, should have their own way in their own concerns; but for himself much more intent on the temporal welfare of his kingdom than on its belief, or the waves of opinion which might blow over it. He had just been very successful in what no doubt seemed to him an enterprise much more kingly and important—the subjugation of the islands. He was happy and prosperous in his private life, his Queen having performed the high duty expected of her in providing the kingdom with an heir, indeed with two sons, to make, as appeared, assurance doubly sure; and though the burning of a heretic was not a pleasant circumstance, Beatoun and the rest of the brotherhood were too clever and helpful as men of the world to be easily dispensed with. James had, there can be no doubt, much reason to be discontented and dissatisfied, as almost all his predecessors had been, with the nobility of his kingdom. Apart from some of those young companions-in-arms who were delightful in the camp and field but useless in the council chamber, his state of mind would seem to have resembled more the modern mood which is represented by the word "bored" than any other more dignified expression. The priests might be fierce (as indeed were the lords, still more) but they were able, and knew something of the necessities of government. The barons disgusted him with their petty jealousies, their want of instruction, their incapacity for any broad or statesmanlike view, and there would seem little doubt that he dispensed with their services as much as possible, and turned to those persons who comprehended him with a natural movement which unfortunately, however, is never fortunate in a king. Something of the severance between himself and those who were nearest to him in rank, which had ruined his grandfather, showed itself as he advanced towards the gravity of manhood: and the fatal name of favourite began to be attached to one man at least in the Court, who would seem to have understood better than the others the ways and intentions of James. But in the meantime the clouds were only gathering; the darkness had not begun. A year or two before, the King had given to the legal faculty of Scotland a form and constitution which it has retained to this day. He had instituted the Court of Session, the "Feifteen," the law lords in their grave if short-lived dignity. He had begun to build and repair and decorate at Holyrood and Linlithgow. "He sent to Denmark," says Pitscottie, "and brought home great horss and meares and put them in parks that their offspring might be gotten to sustein the warres when need was. Also he sent and furnished the country with all kinds of craftsmen such as Frenchmen, Spaniards, and Dutchmen, which ever was the first of their profession that could be had." He went even so far in his desire to develop the natural wealth of his kingdom that he brought over certain German wise men to see if gold could be found in the mines, of which there has always been a tradition, as probably in most countries. All these pacific enterprises occupied James's time and helped on the prosperity of the country. But evil times were close at hand.

One of the first indications that the dreadful round of misfortune was about to begin was the sudden denunciation of James Hamilton, the bastard of Arran, as a conspirator against the King, an event which Pitscottie narrates as happening in the year 1541. He had been a favourite of the King in his youth, and a great champion against the Douglas faction, and it was indeed his intemperate and imprudent rage which determined the fight called Clear the Causeway, and wrought much harm to his own party. He had been high in favour for a time, probably on the ground of his enmity to the house of Angus, then had fallen into discredit, but had lately been employed in certain public offices, and if we may trust Pitscottie, had been put into some such position by the priests as that which Saul of Tarsus held in the service of the persecuting ecclesiastics of Jerusalem. At all events his sudden accusation as plotting against the King's life, and especially as doing so in the interests of the Douglases, was evidently as startling and extraordinary to the great officials to whom the communication was made as it would be to the reader who has heard of this personage only as the infuriated opponent of Angus and his party. No credence seems to have been given to the story at first, though it was told by another Hamilton, a cousin of the culprit. As this happened, however, in the King's absence from Edinburgh, the lords thought it a wise precaution to secure Sir James, and, according to Pitscottie, proceeded in their own dignified persons—the Lord Treasurer, Secretary, and "Mr. Household," preceded by Lyon King-of-Arms—to his lodging in Edinburgh, whence they conveyed him to the castle. Such arrestations would probably cause but little excitement, only a momentary rush and gazing of the crowd as the group with its little band of attendants and defenders passed upward along the High Street, the herald's tabard alone betraying its character. Sir James Hamilton, however, was very well known and little loved, and small would be the sympathy in the looks of the citizens, and many the stern nods and whispers of satisfaction that vengeance had seized him at length. The King, like his representatives, was astonished by the accusation, but when he heard of the terrible "dittay" which had been brought against Hamilton "he came suddenly out of Falkland, where His Grace was for the time, and brought the said Sir James out of the castle to the Tolbooth, and gave him fair assize of the lords and barons, who convicted him of sundry points of treason; and thereafter he was headed and quartered, and his lands annexed to the Crown."

It is a curious question, which however none of the historians think of asking, whether there could be any connection between the scheme, if any, for which the Lady Glamis suffered, and this wholly unexpected outbreak of murderous intention on the part of Hamilton. The Hamiltons and Douglases were sworn enemies, yet greater wonders have been seen than the union of two feudal foes to compass the destruction of the enemy of both. Angus and his brothers banished, but little forgetful of all that had happened, and trusting in the favour of King Henry, were soon to show themselves at the head of expeditions hostile to Scotland across the Border. Were these two sudden disclosures of unexpected treachery the manifestations of a deep-laid plot which might have further developments—if with the bastard of Arran also perhaps in still more unlikely quarters? It is but a conjecture, yet it is one that might seem justified by two isolated events so extraordinary, and by the state of discouragement and misery into which James seems soon to have fallen. Pitscottie relates that the King "took ane great suspition of his nobles, thinking that either one or other of them would deceive him;" and then there began to appear to him "visions in his bed." He thought he saw Sir James Hamilton, fierce and vengeful, appearing to him in the darkness with a drawn sword, with which he cut off the King's right arm. Next time the cruel spectre appeared it upbraided him with an unjust sentence and struck off the other arm: "Now therefore thou sall want both thy armes, and sall remain in sorrow ane while, and then I will come and stryk thy head from thee," said the angry ghost. Whatever may be the reader's opinion about the reality of these visions, there can be little doubt that they show deep depression in the mind of James to whom they came. He woke out of his sleep in great excitement and terror, and told his attendants what he had dreamed, who were very "discontent of his visioun, thinking that they would hear hastily tidings of the same."

"On the morning word came to the King that the prince was very sick and like to die. When the King heard thereof he hasted to Sanct Andros, but, or he could come there the prince was depairted, whereat the King was verrie sad and dolorous. Notwithstanding immediately thereafter the post came out of Stirling to the King showing him that his second son, the Duke of Albany, could not live; and or the King could be in Stirling he was depairted. Whose departures were both within fortie-eight hours, which caused great lamentations to be in Scotland and in especial by the Queen, their mother. But the Queen comforted the King, saying they were young enough, and God would send them more succession."

There is no suggestion, such as might have been natural enough at that age, of poison or foul play in the death of the two infants—nothing but misfortune and fatality and the dark shadows closing over a life hitherto so bright. James was the last of his name: the childless Albany in France, whom Scotland did not love, was the only man surviving of his kindred, and it is not wonderful if the King's heart failed him in such a catastrophe, or if he thought himself doomed of heaven. When this great domestic affliction came to him he was on the eve of a breach with England, brought about not only by the usual mutual aggravations upon the Border, but by other matters of graver importance. King Henry had made many efforts to draw the Scottish King to his side. He had discoursed to him himself by letter, he had sent him not only ambassadors but preachers, he had done everything that could be done to detach the young monarch from the band of sovereigns who were against England, and the allegiance of the Pope. Latterly the correspondence had become very eager and passionate on Henry's side. He had repeatedly invited his nephew to visit him, and many negotiations had passed between them on the subject. The project was so far advanced that Henry came to York to meet James, and waited there for nearly a week for his arrival. But there was great reluctance on the Scottish side to risk their King so far on the other side of the Border. They had suggested Newcastle as a more safe place of meeting, but this had been rejected on the part of the English king. Finally, Henry left York in great resentment, which was aggravated by a defeat upon the Border. Pitscottie tells us that he sent a herald to James declaring that he considered the truce between them broken; that "he should take such order with him as he took with his father before him; for he had yet that same wand to ding him with that dang his father; that is to say, the Duke of Norfolk living that strak the field of Flodden, who slew his father with many of the nobles of Scotland." The King of Scotland thought, the chronicler adds, that these were "uncouth and sharp words"—an opinion in which the reader will agree. But whether Pitscottie is verbally correct or not it is very evident that Henry did not hesitate to rate his nephew in exceedingly sharp and discourteous terms, as for instance bidding him not to make a brute of himself by listening to the priests who would lead any man by the nose who gave them credence. The negotiations altogether were carried on from the English side in a very arrogant manner as comported with Henry's character, made all the more overbearing towards James by their relationship, which gave him a certain natural title to bully his sister's son.

And everything in Scotland was now tending to the miseries of a divided council and a nation rent asunder by internal differences. The new opinions were making further progress day by day, the priests becoming more fierce in their attempts to crush by violence the force of the Reformation—attempts which in their very cruelty and ferocity betrayed a certain growing despair. When Norfolk came to Scotland from Henry—an ill-omened messenger if what is said above of Henry's threat was true—the Scottish gentlemen sought him secretly with confessions of their altered faith; and the ambassador made the startling report to Henry that James's own mind was in so wavering and uncertain a state that if the priests did not drive him into war during the current summer he would confiscate the possessions of the Church before the year was out. But Norfolk's mission, which was in itself a threat, and the presence of the Douglases over the Border, who had never ceased to be upheld by Henry, and whose secret machinations, of which Lady Glamis and James Hamilton had been victims, were now about to culminate in open mischief, all contributed to exasperate the mind of James. That he was not supported as his father had been by the nobility, who alone had the power of giving effect to his call for a general armament, is evident from the first. His priestly counsellors could support him by the imposts which he made freely upon the revenues of the Church, not always without complaint on their part; but they were of comparatively little influence in bringing together the hosts who had to do the fighting; and from the first the nobility,—half of which or more was leavened with Reformation doctrines and felt that their best support was in England—while the whole, almost without exception, resented the prominence of the Church in the national councils, hating and scorning her interference in secular and especially in warlike matters, as is the case in every age,—showed itself hostile. After various incursions on the part of England, made with much bravado and considerable damage, one of which was headed by Angus and his brother George Douglas (this latter, however, being promptly punished and defeated on the spot by the brave Borderers), James made the usual call for a general assembly of forces on the Boroughmuir: but he had advanced only a little way on his march to the Borders when he was stopped by the declaration of the lords that they would only act on the defensive, and would on no account go out of Scotland. The fathers of these same lords had followed James IV, though with the strongest disapproval, to the fatal field of Flodden, their loyalty triumphing over their judgment: but the sons on either side had no such bond between them. James disbanded in disgust the reluctant host, which considered less the honour of Scotland than their own safety; but got together afterwards a smaller army under the leadership of Lord Maxwell, with which to try over again the old issue. Pitscottie's account of the discussions and dissensions, and of all the scorns which subdued James's spirit, is very graphic. Norfolk had led a great body of men into Scotland, who though not advancing very far had done great harm burning and ravaging; but, checked by a smaller force, which held him back without giving battle, had finally retired across the Border, where James was very anxious to have followed him.

"The King's mind was very ardent on battel on English ground, which when the lords perceived they passed again to the council, and concluded that they would not follow the Duke of Norfolk at that time for the King's pleasure, because they said that it was not grounded upon no good cause or reasone, and that he was ane better priests' king nor he was theirs, and used more of priests' counsel nor theirs. Therefore they had the less will to fight with him, and said it was more meritoriously done to hang all such as gave counsel to the King to break his promises to the King of England, whereof they perceived great inconvenients to befall. When they had thus concluded, and the King being advertised thereof, the King departed with his familiar servants to Edinburgh; but the army and council remained still at Lauder."

It was a fatal spot for such a controversy, the spot where, two generations before, the favourite friends and counsellors of James III, whether guilty or not guilty—who can say?—were hanged over the bridge as an example to all common men who should pretend to serve a king whose peers and the nobles of his realm were shut out from the first of his favour. James V had in his train some familiar servants, confidants of his many public undertakings, who were not of noble blood or, at least, of distinguished rank, and his angry withdrawal might well be explained by his determination to save them, if indeed any explanations beyond his vexed and miserable sense of humiliation and desertion were necessary to account for it. He left the lords, whom he would seem to have had no longer either the means or the heart to confront, saying in his rage and shame that he would "either make them fight or flee, or else Scotland should not keep him and them both," and returned to Edinburgh sick at heart to his Queen, who was not in very good health to cheer him—passing, no doubt, with a deepened sense of humiliation through the crowds which would throng about for news, and to whom the spectacle of their King thus returning discomfited was no pleasant sight; if it were not, perhaps, that many among them had now begun to think all failures and disappointments were so many proofs of the displeasure of heaven against one who would not take upon him the office of reformer.

When James heard soon after that his rebellious lords had disbanded their host, he collected a smaller army to revenge the ravages of Norfolk, issuing, according to Pitscottie, a proclamation bidding all who loved him be ready within twenty-four hours "to follow the King wherever he pleased to pass"; but even this new levy was little subordinate. After it had penetrated a little way into England a fatal mistake arose—an idea that Oliver Sinclair, the King's "minion," whom he had sent to read a manifesto to the army, had been appointed its general—upon which the new bands, disgusted in their turn, fell into a forced retreat, and getting involved in the broken ground of Solway Moss were there pursued and surrounded by the English, miserably defeated and put to flight. "There was but ane small number slain in the field," says Pitscottie, "to wit, there was slain on both sides but twenty-four, whereof was nine Scottishmen and fifteen Englishmen"; a very great number, however, were taken prisoners, many of the gentlemen, it is suggested, preferring captivity to the encounter of the King after such an inexcusable catastrophe. We are not told why it was that James had not himself taken the command of his army. He does not even seem to have accompanied it, perhaps fearing that personal opposition which was an insult to a king in those days.

"When these news came to the King of Scotland where he was for the time, how his lords were taken and had in England, and his army defaitt, he grew wondrous dollorous and pensive, seeing no good success to chance him over his enemies. Then he began to remord his conscience, and thought his misgovernance towards God had the wyte therof and was the principal cause of his misfortune; calling to mind how he had broken his promise to his uncle the King of England, and had lost the hearts of his nobles throw evil counsel and false flattery of his bishops, and those private counsellors and his courtiers, not regarding his wyse lords' counsels."

"He passed to Edinburgh," adds the chronicler, "and there remained eight days with great dollour and lamentation for the tinsell (loss) of his lieges and shame to himself." Discouragement beyond the reach of mortal help or hope seemed to have taken hold of the unfortunate King. He saw himself alone, no one standing by him, his nobles hostile, his people indifferent; he had vowed that Scotland should not be broad enough to hold both them and him, but he had no power to carry out this angry threat. His life had been threatened in mysterious ways; he had lost his children, his confidence in himself and his fortunes; last and worst of all, he was dishonoured in the eyes of the world. His army had refused to advance, his soldiers to fight. He was the King, but able to give effect to none of a king's wishes—neither to punish his enemies nor to carry out his promises. He who had done so much for his realm could do no more. He who had ridden the Border further and swifter than any man-at-arms to carry the terror of justice and the sway of law—who had daunted the dauntless Highlands and held the fiercest chiefs in check—who had been courted by pope and emperor, and admired and feasted at the splendid Courts of France—he who had been the King of the Commons, the idol of the people—was now cast down and miserable, the most shamed and helpless of kings.

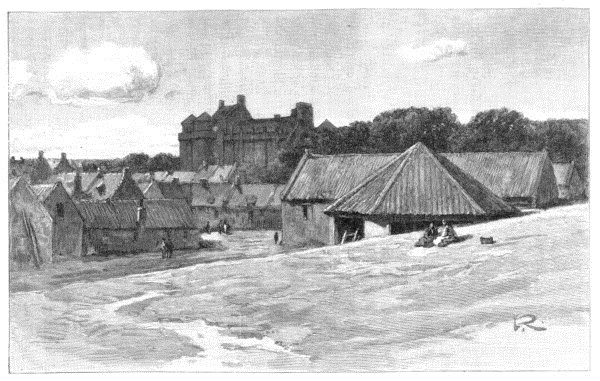

There seems no reason why James should have so entirely lost heart. There had already been moments in his life when he had suffered sore discouragement and overthrow, yet never had been overcome. But now it is clear he felt himself at the end of his resources. How could he ever hold up his head again? a man who could not keep his own kingdom from invasion, or avenge himself upon his enemies! After he had lingered a little in Edinburgh, where the Queen was now near the moment which should give another heir to Scotland, he left the capital—perhaps to save her at such a time from the sight and the contagion of his despair—and crossed the Firth to Falkland, a place so associated with stirring passages in his career. But there his sickness of heart turned to illness of body; he became so "vehement sick" that his life was despaired of; he was "very near strangled to death by extreme melancholie." One hope remained, that the Queen might restore some confidence to his failing strength and mind by an heir to the crown, another James, for whom it might be worth while to live. James sent for some of his friends, "certain of his lords, both spiritual and temporal," to help him to bear this time of suspense, and advise him what might yet be done to set matters right, who surrounded him, as may be imagined, very anxiously, fearing the issue.

"By this the post came out of Linlithgow showing the King good tidings that the Queen was delivered. The King inquired whether it was man or woman. The messenger said it was ane fair dochter. The King answered and said, 'Farewell! it came with ane lass, and it will pass with ane lass,' and so commended himself to Almighty God, and spoke little from thereforth, but turned his back to his lords and his face to the wall."

Even at this bitter moment, however, the dying Prince was not left alone with his last disappointment. Cardinal Beatoun, whose influence had been so inauspicious in his life, pressed forward, "seeing him begin to fail of his strength and natural speech," and thrust upon him a paper for his signature, "wherein the Cardinal had writ what he pleased for his own particular weill," evidently with some directions about the regency, that ordeal which Scotland, unhappily, had now again to go through. When James had put his dying hand to this authority, wrested from him in his last weakness, a faint light of peace seems to have fallen across his death-bed.

FALKLAND PALACE

"As I have shown you, he turned him upon his back, and looked and beheld his lords around about, and gave ane little lauchter, syne kissed his hand and gave it to all his lords about him, and thereafter held up his hands to God and yielded the spirit."

There are many pathetic death scenes in history, but few more touching. His father, after a splendid and prosperous life, had fallen "in the lost battle, borne down by the flying;" he, after a career almost as chivalrous and splendid and full of noble work for his country, in a still more forlorn overthrow; his hopes all gone from him, his strength broken in his youth. Nothing, it would seem, could save these princes, so noble and so unfortunate. It was enough to bear the name of James Stewart to be weighed down by cruel Fate. But before his spirit shook off the mortal coil a ray of peace had shot through the clouds; he looked upon the anxious faces of his friends, some of whom at least must surely have been true friends, bound to him by comradeship and brotherhood, with that low laugh which is one of the most touching expressions of weakened and failing humanity—love and kindness in it, and a certain pleasure to see them round him; and yet to be free of it all—the heavy kingship, the hopes that ever failed, the friends that so rarely were true. The lips that touched that cold hand which he kissed before he gave to them must have trembled, perhaps with compunction, let us hope with some vow of fidelity to his memory and trust.