Полная версия

Полная версияRoyal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

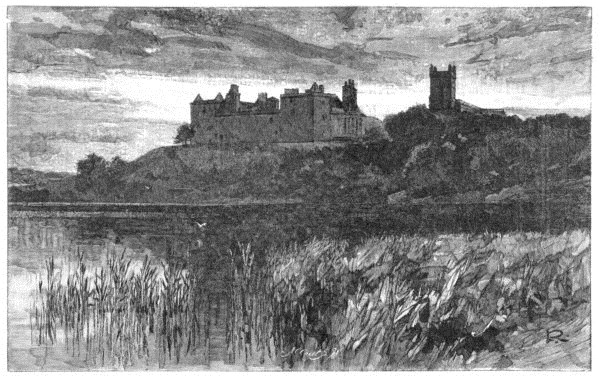

LINLITHGOW PALACE

Other and still more serious matters were now, however, surging upwards in both England and Scotland, which doubled the silent struggle between the old ally and the new. On the side of France was the old religion, the Church which at this period was the strongest of the Estates of Scotland, richer than any of the others, and possessing almost all the political ability of the time: on the side of England a new, scarcely recognised, but powerful influence, which was soon to attain almost complete mastery in Scotland and shatter that Church to pieces. In the beginning of James's reign this new power was but beginning to swell in the silent bosom of the country, showing here and there in a trial for heresy and in the startling fires of execution which cut off the first martyrs for the reformed faith. But there is no evidence to show that James, a young man full of affairs much more absorbing than religious controversy, with more confidence, politically at least, in the Church than in any other power of his realm, had ever been awakened to the importance of the struggle. The smoke of those fires which blew over all Scotland in potent fumes from St. Andrews, on the further side of the Firth; and from Edinburgh, where on the Castle Hill in the intervals of the tiltings and tourneys, the Vicar of Dollar for example, of whose examination we have a most vivid and admirable report, full of picturesque simplicity, not without humour even in the midst of the tragedy, was burnt—along with several gentlemen of his county: does not seem to have reached the young King, absorbed in some project of State, or busy with new laws and regulations, or inspecting the portraits of the great ladies among whom he had to choose his bride. There is a curious story communicated in a letter of one of the English envoys of the period of his conversation with a Scotch gentleman, in which we find a description of James listening to a play represented before the Court at the feast of the Epiphany, 1540, in the Castle of Linlithgow. This play is believed to have been Sir David Lindsay's Satire on the Three Estates, one of the most effective attacks upon the corruptions of the Church which had ever been made, and setting forth the exactions of the priests from the peasantry and the poor at every event of their lives, as well as the wealth and wickedness of the monastic communities, of which Scotland was full, and which had long been the recognised object of popular satire and objurgation. The performance would seem to have had as great an effect upon the young King as had the play in Hamlet upon the majesty of Denmark. James turned to Beatoun (the Cardinal, nephew and successor of Archbishop James) the Chancellor in indignant remonstrance. Were these things so? and if they were, would not the bishops and other powerful ecclesiastics join to repress them? Let them do so at once, cried the sovereign: or if not he should send half a dozen of the proudest of them to King Henry to be dealt with after his methods. Even Churchmen had occasionally to brook such threats from an excited prince. Beatoun answered with courtier-like submission that a word from the King was enough, upon which James, not wont to confine himself to words, and strong in the success with which he had overcome one of his Estates, the lords, now so quiet under his hand, replied that he would not spare many words for such an issue. This characteristic scene is very interesting. But probably when the memory of what he had heard faded from the busy King, and the tumult of public events gained possession again of his ear and mind, he forgot the sudden impression, or contented himself with the thought that Beatoun and the bishops must put order in their own affairs. Pitscottie tells us in respect to a projected visit to England, vaguely thought of and planned several years before this time, that "the wicked bishops of Scotland would not thole" a meeting between James and Henry. "For the bishops feared that if the King had met with King Henry that he would have moved him to casten down the abbeys, and to have altered the religion as the King of England had done before. Therefore the bishops bade him to bide at home, and gave him three thousand pounds of yearly rent out of their benefices." It is to be feared that history has no evidence of this voluntary munificence, but James found the ecclesiastical possessions in Scotland very useful for the purposes of taxation, and in this respect did not permit Beatoun to have his own way.

When the young King was in his twenty-fourth year he found himself able—many previous negotiations on the subject having come to nothing—to pay a visit to the Continent in his own person in order to secure a wife. It is a greater testimony to the personal power and vigour of James than any mere details could give that, within eight years of the time when, a boy of sixteen, he had escaped from the power of the Douglas, it should be possible for him to leave, after all the wild anarchy of his minority, a pacificated and orderly kingdom behind him, in the care of a Council of Regency, while he went forth upon a mission so important to himself. He had altogether extinguished and expelled the house of Douglas; he had subdued and repressed other turbulent lords, and convinced them that his authority was neither to be neutralised nor made light of; he had settled and calmed the Border by the most decisive means; and he was now free to show himself in the society of kings, and win his princess, and see the world. He had been already the object of many overtures from contemporary Powers. The Emperor and the Pope had both sent him envoys and conciliated his friendship; and in the imperial house itself as well as in many others of the highest rank there had been ladies proposed to share his crown. The one more immediately in view when he set out on his journey was a daughter of the Duke of Vendôme. The defeat of Charles V before Marseilles took place almost simultaneously with James's arrival, and the Scotch chroniclers do not lose the opportunity of asserting that it was the coming of the King of the Scots with a supposed army of twenty thousand men to the succour of France which was the reason of the Emperor's precipitate withdrawal. Pitscottie narrates, with more evident truthfulness, how the Frenchmen on the Norman coast were alarmed by the ships, fearing it to be an enemy which hove in sight, "for there were many strangers in his companie, so that he appeared ane great army." But the sight of the red lion of Scotland changed their alarms into joy, and they welcomed the Scots King and party, "at the New Haven beside Diep," with much rejoicing. He would seem to have pushed across France to the Court of Vendôme without pausing to pay his respects to the King at Paris; and we find his movements recorded in a romantic tale, which is neither contradicted nor supported by other authorities, but likely enough to a romantic young prince upon a love-quest. According to this description James did not assume his proper character but appeared only as one among the many knights, who probably represented themselves, to make his feint successful, as merely a party of cavaliers seeking adventure and the exercises of chivalry. He intended thus to see, while himself unknown, "the gentlewoman who sould have been his spouse, thinking to spy her pulchritud and behaviour unkenned by her."

"Notwithstanding this fair ladie took suspition that the King of Scotland should be in the companie, wherefore she passed to her coffer and took out his picture, which she had gotten out of Scotland by ane secret moyane, and as soon as she looked to the picture it made her know the King of Scotland incontinent where he stood among the rest of his companie, and past peartlie to him, and took him by the hand, and said, 'Sir, ye stand over far aside; therefore, if it please your Grace, you may show yourself to my father or me, and confer and pass the time ane while.'"

Perhaps it was injudicious of the fair ladie to be so "peart." At all events, after much feasting, "nothing but merriness and banquetting and great cheer and lovelie communing betwixt the King's grace and the fair ladies, with great musick and playing on instruments, and all other kinds of pastime for the fields," as well as "jousting and running of great horses," the ungrateful James "thought it expedient to speak nothing of marriage at that time, till he had spoken with the King of France, considering," adds the chronicler, who perhaps sees an excuse to be necessary, "he was within his realm he would show him his mind and have his counsel thereto before he concluded the matter." Pitscottie thus saves the feelings of the lady of whom other historians say curtly that she did not please the King. But when the Scottish band reached the Court, though it was then in mourning for the Dauphin, recently dead, King James was received with open arms. The King of France, sick and sad for the loss of his son, was in the country at a hunting seat, and when James was suddenly introduced at the door of his chamber as "the King of Scotland, sire, come to comfort you," the arrival evidently made the best possible impression. The sorrowful father declared, as he embraced the young stranger, that it was as if another son had been given him from heaven; and after a little interval the royal party, increased by James's Scottish train, moved on to another palace. We may be allowed to imagine that the Queen and her ladies came out to meet them, as the first sight which James appears to have had of his future bride was while she was "ryding in ane chariot, because she was sickly, and might not ryd upon hors." Magdalen, too, saw him as he rode to meet the fair cavalcade in her father's company, who looked so much happier and brighter from the encounter with this gallant young prince. The poor girl was already stricken for death, and had but a few months to live; but it is very likely that her malady was that fatal but deceitful one which leaves a more delicate beauty to its victims, and gives feverish brightness to the eyes and colour to the cheek. A tender creature, full of poetry and imagination, and most likely all unconscious of the fate that hung over her, she loved the gallant cavalier from the first moment of seeing him, and touched the heart of James by that fragile beauty and by the affection that shone in her soft eyes. It was a marriage that no one approved, for her days were known to be numbered. But perhaps some faint hope that happiness, that potent physician, might arrest disease, as it has been known to do, prevailed both with the anxious father and the young man beloved, in whom tender pity and gratitude replaced a warmer sentiment. At all events the marriage took place in Paris, in the noble church of Notre Dame, in the beginning of the year 1537. The King, we are told, sent to Scotland to invite a number of other noblemen and gentlemen to attend his wedding, which was performed with the greatest pomp and splendour. Not until May did the young couple set out for their home, and then they were laden with gifts, two ships being presented to them, a number of splendid horses fully caparisoned, and quantities of valuable tapestries, cloth of silver and gold, and jewels of every description. Perhaps the long delay was intended to make the journey more safe for the poor young Queen. The voyage from Dieppe to Leith lasted five days, and the bridal party was accompanied by an escort of "fiftie ships of Scottismen, Frenchmen, and strangers." "When the Queen was come upon Scottis eard, she bowed her down to the same, and kissed the mould thereof, and thanked God that her husband and she were come safe through the seas." There could not be a more tender or attractive picture. How full of poetry and soft passion must the gentle creature have been who thus took possession of the land beloved for her young husband's sake! The Scottish eard indeed was all that she was to have of that inheritance, for in little more than a month the gentle Magdalen was dead. She was laid in the chapel of the palace which was to have been her home, with "ane dolorous lamentation; for triumph and merriness were all turned into dirges and soul-masses, which were very lamentable to behold."

This sad story is crowned by Pitscottie with a brief note of the death of the Duc de Vendôme's daughter, "who took sick displeasure at the King of Scotland's marriage that she deceased immediately thereafter; whereat the King of Scotland was highly displeased, thinking that he was the occasion of that gentlewoman's death." Other historians say that this tragical conclusion did not occur, but that the Princess of Vendôme was married on the same day as James. Pitscottie's is the more romantic ending, and rounds the pathetic tale.

After such a mournful and ineffectual attempt at married life all the negotiations had to be begun over again, and James was at last married, to the general satisfaction, to Mary of Guise, a woman, as it turned out, of many fine and noble qualities, to which but indifferent justice was ever done. It was before this event, however, and immediately after the death of the Queen, that a curious and tragical incident happened, which furnished another strange scene to the many associations of Edinburgh. This was the execution of Lady Glamis upon the Castle Hill for witchcraft and secret attempts upon the life of the King by means of magic or of poison. No one seems to know what these attempts were. Pitscottie gives this extraordinary event a short paragraph. The grave Pinkerton fills a page or two with an apology or defence of James for permitting such an act. But we are not told what was the evidence, or how the sovereign's life was threatened. The supposed culprit was however—and the fact is significant—the only member of the family of Angus left in Scotland, the sister of the Earl. Once more the Castle Hill was covered with an awed or excited crowd, not unaccustomed to that sight, for the heretics had burnt there not long before, but at once more and less moved than usual, for the victim was a woman fair and dignified, such a sufferer as always calls forth the pity of the spectators, but her crime witchcraft, a thing held in universal horror, and with which there would be no sympathisers. Few, if any, in that crowd would be so advanced in sentiment as to regard the cruel exhibition with the horrified contempt of modern times. The throng that lined that great platform would have no doubt that it was right to burn a witch wherever she was found; and the beauty of the woman and the grandeur of her race would give a pang the more of painful satisfaction in her destruction. But it is strange that thus a last blow should have been aimed at that family, once so great and strong, which James's resentment had pursued to the end. A little while before, Archibald Douglas of Kilspindie had thrown himself upon James's mercy—the only member of the Douglas family who can be in any way identified with the noble Douglas of The Lady of the Lake.

"'Tis James of Douglas, by St. Serle,The uncle of the banished Earl."But Archibald of Kilspindie did not meet the same forgiveness with which his prototype in the poem was received. He was sent back into banishment unforgiven, the King's word having been passed to forgive no one condemned by the law. Perhaps the same stern fidelity to a stern promise was the reason why Lady Glamis was allowed to go to the stake unrescued. But we speculate in vain on subjects so veiled in ignorance and uncertainty. Perhaps his counsellors acted on their own authority in respect to a crime the reprobation and horror of which were universal, and did not disturb the King in the first shock of his mourning. In the same week the fair and fragile Magdalen of France was carried to her burial, and Lady Glamis was burned at the other extremity of Edinburgh. Perhaps it was supposed that something in the incantations of the one had a fatal influence upon the young existence of the other. At all events these two sensations fell to the populace of Edinburgh and all the strangers who were constantly passing through her gates, at the same time. Life in those days was full of pictorial circumstances which do not belong to ours. One is inclined to wonder sometimes whether the many additional comforts we possess make up for that perpetual movement in the air, the excitement, the communication of new ideas, the strange sights both pleasant and terrible. The burning of a witch or a heretic is perhaps too tremendous a sensation to be desired by the most heroic spectator; but the perpetual drama going on thus before the eyes of all the world, and giving to the poorest an absolute share in every new and strange thing, must have added a reality to national life which no newspapers can give. That the people remain always eager for this share in historical events, the crowds that never weary of gazing at passing princes, the innumerable audience of the picture papers, the endless reproduction of every insignificant public event, from a procession of aldermen to the simplest day's journey of a royal personage, abundantly testify. In the days of the Jameses few of the crowd could read, and still fewer had the chance of reading. A ballad flying from voice to voice across the country, sung at the ingle-neuk, repeated from one to another in the little crowd at a "stairhead," in which the grossest humorous view was the best adapted for the people, represented popular literature. But most things that went on were visible to the crowding population. They saw the foreign visitors, the ambassadors, the knights, each with his distinguishable crest, who came to meet in encounter of arms the knights of the Scottish Court. All that went on they had their share in, and a kind of acquaintance with every notability. The public events were a species of large emblazoned history which he who ran could read.

These ballads above referred to came to singular note, however, in one of the many discussions between England and Scotland which were carried on by means of the frequent envoys sent to James from his uncle. The Borders, it appears, were full of this flying literature sent forth by unknown writers, and spread probably by, here and there, a wandering friar, more glad of a merry rhyme than disconcerted by a satire against his own cloth, or with still more relish dispersing over the countryside reports of King Henry's amours and divorces, and of the plundering of abbeys and profane assumption of sacred rights by a monarch who was so far from sanctified. Popular prophecies of how a new believing king should be raised up to disconcert the heretics, and on the northern side of the Border of the speedy elevation of James to the throne of England, and final victorious triumph of the Scottish side, flew from village to village, exciting at last the alarm of Henry and his council, who made formal complaint of them at the Scottish Court, drawing from James a promise that if any of his subjects should be found to be the authors of such productions they should suffer death for it—a heavy penalty for literary transgression. In Scotland farther north it was another kind of ballad which was said and sung, or whispered under the breath with many a peal of rude laughter, the Satires of "Davy Lindsay" and many a lesser poet—ludicrous stories of erring priests and friars, indecent but humorous, with lamentable tales of dues exacted and widows robbed, and all the sins of the Church, the proud bishop and his lemans, the avaricious priest and his exactions, the confessors who bullied a dying penitent into gifts which injured his family, and all the well-worn scandals by which in every time of reformation the coarser imagination of the populace is stirred. If James himself was startled into an angry demand how such things could be after he had witnessed the performance of David Lindsay's play, which was trimmed into comparative decency for courtly ears, it may be supposed what was the effect of that and still broader assaults, upon the unchastened imagination of the people. The Reformation progressed by great strides by such rude yet able help as well as by the purer methods of religion. The priests, however, do not seem to have made war on the balladmakers, as the great King of England would have had his nephew do. Buchanan, indeed, whose classic weapons had been brought into this literary crusade, and who also had his fling at the Franciscans as well as his coarser and more popular brethren, was imprisoned for a time, and had to withdraw from his country, but the poets of the people, far more effective, would seem to have escaped.

All this, however, probably seemed of but little importance to James in comparison with the greater affairs of the kingdom of which his hands were full. When the episode of his marriages was over, and still more important an heir secured, he returned to that imperial track in which he had acquitted himself so well. All would seem to have been in order in the centre of the kingdom; the Borders were as quiet as it was possible for the Borders to be; and only the remote Highlands and islands remained still insubordinate, in merely nominal subjection to the laws of the kingdom. James, we are told, had long intended to make one of the royal raids so familiar to Scottish history among his doubtful subjects of these parts, and accordingly an expedition was very carefully prepared, twelve ships equipped both for comfort and for war, with every device known to the time for provisioning them and keeping them in full efficiency. We are told that the English authorities looking on, were exceedingly suspicious of this voyage, not knowing whither such preparations might tend, while all Scotland watched the setting out of the expedition almost as much in the dark as to its motive, and full of wonder as to where the King could be going. Bonfires were blazing on all the hilltops in rejoicing for the birth of a prince when James took his way with his fleet down the Firth. Pinkerton, who ought to have known better, talks of "the acclamations of numerous spectators on the adjacent hills and shores" as if the great estuary had been a little river. It might well be that both in Fife and Lothian there were eager lookers-on, as soon as it was seen that the fleet was in motion, to see the ships pass: but their acclaims must have been loud indeed to carry from Leith to Kinghorn. The King sailed early in June 1540 towards the north. Many a yacht and pleasure ship still follows the same route round the Scottish coast towards the wild attractions of the islands.

"Merrily, merrily, bounds the bark,She bounds before the gale,The mountain breeze from Ben-na-darchIs joyous in her sail.With fluttering sound like laughter hoarseThe cords and canvas strain,The waves divided by her forceIn rippling eddies chased her courseAs if they laughed again."But it was on no pleasure voyage that James had set out. He had in his twelve ships two thousand armed men, led by the most trusted lords of Scotland, and his mission was to reduce to order the clans who knew so little what a king's dignity was, or the restraints of law, or the pursuits of industry. No stand would seem to have been anywhere made against him. Many of the chiefs of the more turbulent tribes were brought off to the ships, not so much as prisoners in consequence of their own misdoings, but as hostages for their clans: and the startled isles, overawed by the sight of the King and his great ships, and by the more generous motive of anxiety for their own chieftains in pledge for them, calmed down out of their wild ways, and ceased from troubling in a manner unprecedented in their turbulent history.

An incidental consequence of this voyage sounds oddly modern, as if it might have been a transcript from the most recent records. James perceived, or more probably had his attention directed to the fact, that the fishermen of the north were much molested by fishing vessels from Holland, Flanders, and the Scandinavian coasts, who interfered with their fishing, sometimes even thrusting them by violence of arms out of their own waters. The King accordingly detached one or two of his vessels under the command of Maxwell, his admiral, to inquire into these high-handed proceedings, with the result that one of the foreign fisher pirate-ships was seized and brought to Leith to answer for their misdoings. There they were reprimanded and bound over to better behaviour, then dismissed without further penalty. How little effectual, however, this treatment was, is exemplified by the fact that the selfsame offence continues to be repeated until this very day.