Полная версия

Полная версияRoyal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

But Edinburgh was the centre of all the feasting and splendour which distinguished his time. The lists were set before the castle gates, on that lofty and breezy plateau where all the winds blow. Sometimes there were bands of foreign chivalry breaking lances with the high Scottish nobles according to all the stately laws of that mimic war; sometimes warriors of other conditions, fighting Borderers or Highlanders, would meet for an encounter of arms, ending in deadly earnest, which was not discouraged, as we are told with grim humour, since it was again to the realm to be disembarrassed of these champions at any cost, and the best way was that they should kill each other amicably and have no rancour against Justiciar or King. Among the foreign guests who visited James was Bernard Stuart of Aubigny, Monsieur Derbine, as Pitscottie calls him, the representative of a branch of the royal race which had settled in France, whom James received, his kinsman being an old man, with even more than his usual grace, making him the judge in all feats of chivalry "at justing and tourney, and calling him father of warres, because he was well practised in the same." Another of the visitors, Don Pedro d'Ayala, the Spanish grandee who helped to conduct the quarrel over Perkin Warbeck to a great issue, wrote to his royal master a description of King James, which is highly interesting, and full of unconscious prophecy. The Spaniard describes the young monarch at twenty-five as one of the most accomplished and gallant of cavaliers, speaking Latin (very well), French, German, Flemish, Italian, and Spanish; a good Christian and Catholic, hearing two masses every morning; fond of priests—a somewhat singular quality unless such jovial priests and boon-companions as Dunbar, the poet-friar, were the subject of this preference; though perhaps the seriousness which mingled with his jollity, the band of iron under his silken vest, led him to seek by times the charm of graver company, the mild and learned Gavin Douglas and other scholars in the monasteries, where thought and learning had found refuge. The following details, which are highly characteristic, bring him before us with singular felicity, and, as afterwards turned out, with a curious foreseeing of those points in him which brought about his tragical end.

"Rarely even in joking a word escapes him which is not the truth. He prides himself much upon it, and says it does not seem to him well for kings to swear their treaties as they do now. The oath of a king should be his royal word as was the case in bygone ages. He is courageous even more than a king should be. I have seen him even undertake most dangerous things in the late wars. I sometimes clung to his skirts and succeeded in keeping him back. On such occasions he does not take the least care of himself. He is not a good captain, because he begins to fight before he has given his orders. He said to me that his subjects serve him with their persons and goods, in just or unjust quarrels, exactly as he likes; and that therefore he does not think it right to begin any warlike undertaking without being himself the first in danger. His deeds are as good as his words. For this reason, and because he is a very humane prince, he is much loved."

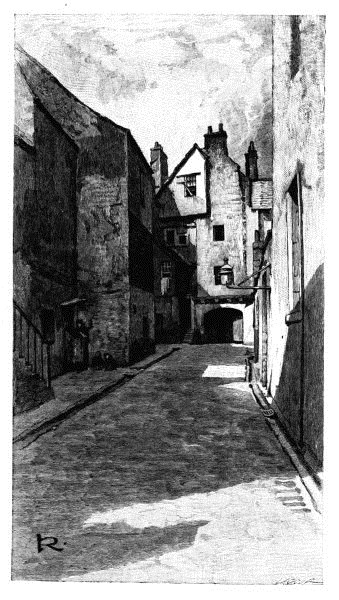

BAKEHOUSE CLOSE

The perfect reason yet profound unreasonableness of this quality in James, so fatally proved in his after history, is very finely discriminated by the writer, who evidently had come under the spell of a most attractive personality in this young sovereign, so natural and manful, so generous and true. That James should acknowledge the penalty of the fatal power he had to draw a whole nation into his quarrel, just or unjust, by risking himself the first, is so entirely just according to every rule of personal honour, yet so wildly foolish according to all higher policy; exposing that very nation to evils so much greater than the worst battle. Flodden was still far off in the darkness of the unknown, but had this description been written after that catastrophe, it could not more clearly have disclosed the motives and magnanimity but tragic unwisdom of this prince of romance.

The Spaniard adds much praise of James's temperance, a virtue indifferently practised by his subjects, and of his morality, which is still more remarkable. The amours and intrigues of his youth, Don Pedro informs his king, this young hero had entirely renounced, "or so at least it is believed," partly "from fear of God, and partly from fear of scandal," which latter "is thought very much of here"—a curious touch, which would seem to indicate a magnificent indifference to public opinion, not shared by the little northern Court, in the haughtier circles of Madrid. The picture is perhaps a little flattered; and it is hard to imagine how James could have picked up so many languages in the course of what some writers call a neglected education, confined to Scotland alone; but perhaps his father's fondness for clever artificers and musicians may have made him familiar in his childhood with foreign dependants, more amusing to a quick-witted boy than the familiar varlets who had no tongue but "braid Scots." "The King speaks besides," says Ayala, "the language of the savages who live in some parts of Scotland and in the islands"; clearly in every sense of the word a man of endless accomplishments and personal note, quite beyond the ordinary of kings.

At no time, according to unanimous testimony, had Scotland attained so high a position of national wealth, comfort, and prosperity. The wild Highlands had been more or less subdued by the forfeiture of the traditionary Lord of the Isles, and the final subjection of that lawless region, nominally at least, to the King's authority, and with every precaution for the extension of justice and order to its farthest limits. A navy had suddenly sprung into being, signalising itself in its very birth by brilliant achievements and consisting of vessels few indeed, but of exceptional size and splendour, as great for their time as the great Italian ironclads are for this, and like them springing from something of the bravado as well as for the real uses of a rapidly growing power. And there had been peace, save for that little passage of arms on account of Perkin Warbeck, throughout all the reign of James—peace to which the warlike Scots seem to have accustomed themselves very pleasantly, notwithstanding that on the one side of the Border as on the other there was nothing so popular as war between the neighbour nations; but the exploits of Sir Andrew Wood with his Yellow Carvel, and the Great Michael lying there proudly on the Firth, ready to sweep the seas, afforded compensation for the postponement of other struggles.

It was in these circumstances that the negotiations for James's marriage with the little Margaret, Princess Royal of England, and in every way, as it turned out, a true Tudor, though then but an undeveloped child, took place. The gallant young King, then seven or eight and twenty, in the plenitude of his manhood, was not anxious for the bride of ten persistently offered to him by her royal father; and the negotiations lagged, and seemed to have gone on à plusieurs reprises for several years. But at length by the persistent efforts of Henry VII, who saw all the advantages of the union, and no doubt also of councillors on the Scots side, who felt that the continued prosperity of the country was best secured by peace, it was brought about in 1504, when James must have been just over thirty and Margaret was twelve—a very childish bride, but probably precocious, and not too simple or ignorant, as belonged to her violent Tudor blood. He "was married with her solemnedlie by the advice of the nobilitie of England and Scotland, and gatt great summes of money with her: and promise of peace and unity made and ordained to stand between the two realms," says Pitscottie. The great sums, however, seem problematical, as the dower of Margaret was not a very large one, and the sacrifices made for her were considerable—the town of Berwick being given up to England as one preliminary step. The event, however, was one of incalculable importance to both nations, securing as it did the eventual consolidation in one of the realm of Great Britain, though nobody as yet foresaw that great consequence that might follow. Along with the marriage treaty was made one of perpetual peace between England and Scotland—a treaty indeed not worth the paper it was written upon, yet probably giving comfort to some sanguine spirits. Had the prudent old monarch remained on the throne of England as long as James ruled in Scotland it might indeed never have been broken; but Henry was already old, and his son as hot-headed as the cousin and traditionary adversary now turned into a brother. Margaret was conveyed into Scotland with the utmost pomp, and Edinburgh roused itself and put on decorations like a bride to receive the little maiden, so strangely young to be the centre of all these rejoicings: her lofty houses covered with flutterings of tapestries and banners and every kind of gay decoration, and her windows filled with bright faces, coifs, and veils, and embroideries of gold that shone in the sun. The dress worn by James, as he carried his young bride into Edinburgh seated on horseback behind him, is fully described for the benefit of after ages. He wore a jacket of cloth of gold bordered with purple velvet, over a doublet of purple satin, showing at the neck the collar of a shirt embroidered with pearls and gold, with scarlet hose to complete the resplendent costume. At his marriage he wore a jacket of crimson satin over a doublet of cloth of gold, with the same scarlet hose, and a gown of white damask brocaded with gold over all. No doubt the ladies were not behind in this contest of brave apparel. Grey Edinburgh, accustomed this long time to the dull tones of modern habiliments, sparkled and shone in those days of finery and splendour. The streets were meant for such fine shows; its stairheads and strong deep doorways to relieve the glories of sweet colour, plumes, and jewels. When the lists were set on the summit of the hill, the gates thrown up, the garrison in their steel caps and breastplates lining the bars, and perhaps the King himself tilting in the mêlée, while all the ladies were throned in their galleries like banks of flowers, what a magnificent spectacle! The half-empty streets below still humming with groups of gazers not able to squeeze among the throngs about the bars, but waiting the return of the splendid procession: and more and more banners and tapestries and guards of honour shining through the wide open gates of the port all the way down to Holyrood. There was nothing but holiday-making and pleasure while the feasting lasted and the bridal board was yet spread.

While this heydey of life lasted and all was bright around and about the chivalrous James, there was a certain suitor of his Court, a merry and reckless priest, more daring in words and admixtures of the sacred and the profane than any mere layman would venture to be, whose familiar and often repeated addresses to the King afford us many glimpses into the royal surroundings and ways of living, as also many pictures of the noisy and cheerful mediæval town which was the centre of pleasures, of wit and gay conversation, and all that was delightful in Scotland. Dunbar's title of fame is not so light as this. He was one of the greatest of the followers of Chaucer, a master of melody, in some points scarcely inferior to the master himself whose praise he celebrates as

"Of oure Inglisch all the lightSurmounting every tong terrestrialAlls far as Mayis morrow dois mydnyght."But it is unnecessary here to discuss the "Thrissil and the Rois," the fine music of the epithalamium with which he celebrated the coming of Margaret Tudor into Scotland, or the more visionary splendour of the "Golden Targe." The poet himself was not so dignified or harmonious as his verse. He possessed the large open-air relish of life, the broad humour, sometimes verging on coarseness, which from the time of James I. to that of Burns has been so singularly characteristic of Scots poetry: and found no scene of contemporary life too humble or too ludicrous for his genius—thus his more familiar poems are better for our purpose than his loftier productions, and show us the life and fashion of his town and time better than anything else can do. This is one, for example, in which he upbraids "the merchantis of renown" for allowing "Edinburgh their nobil town" to remain in the state in which he describes it:—

"May nane pass through your principall gatesFor stink of haddocks and of skates,For cryin' of carlines and debates,For fensome flytings of defame.Think ye not shameBefore strangers of all estatesThat sic dishonour hurt your name?"Your stinkand schule that standis dirkHalds the light from your Parroche Kirk,Your forestairs makis your houses mirkLike na country but here at hameThink ye not shame,Sa little policie to workIn hurt and sklander of your name?"At your hie Croce, where gold and silkShould be, there is but curds and milk,And at your Tron but cokill and wilk,Pansches, puddings, of Jok and Jame.Think ye not shameKin as the world sayis that ilkIn hurt and sklander of your name?"Thus old Edinburgh rises before us, beautiful and brave as she is no longer, yet thronged about the Netherbow Port, and up towards the Tron, the weighing-place and centre of city life, with fishwives and their stalls, with rough booths for the sale of rougher food, and with country lasses singing curds and whey, as they still did when Allan Ramsay nearly four hundred years after succeeded Dunbar as laureate of Edinburgh. Notwithstanding, however, these defects the Scottish capital continued to be the home of all delights to the poet-priest. When his King was absent at Stirling, Dunbar in the pity of his heart sang an (exceedingly profane) litany for the exile that he might be brought back, prefacing it by the following compassionate strain:—

"We that are here in Hevinis gloryTo you that are in PurgatoryCommendis us on our hairtly wyiss,I mean we folk in Paradyis,In Edinburgh with all merrinessTo you in Strivilling in distress,Where neither pleasance nor delyt is,For pity thus ane Apostle wrytis."O ye Heremeitis and HankersaidillisThat takis your penance at your tabillis,And eitis nocht meit restorativeNor drinkis no wyne comfortativeBot aill, and that is thyn and small,With few courses into your hall;But (without) company of lordis or knightsOr any other goodly wightis,Solitar walkand your alloneSeeing no thing but stok and stone,Out of your powerfull PurgatoryTo bring you to the bliss of gloryOf Edinburgh the merry toun,We sall begin ane cairfull soun,And Dirige devout and meikThe Lord of bliss doing besiekYou to delyvre out of your noyAnd bring you soon to Edinburgh joy,For to be merry among us,And so the Dirige begynis thus."Many are the poet's addresses to the King in happier circumstances when James is at home and in full enjoyment of these joys of Edinburgh. His prayers for a benefice are sometimes grave and sometimes comic, but never-failing. He describes solicitors (or suitors) at Court, all pushing their fortune. "Some singis, some dancis, some tells storyis." Some try to make friends by their devotion, some have their private advocates in the King's chamber, some flatter, some play the fool—

"My simpleness among the laveWist of na way so God me save,But with ane humble cheer and faceReferris me to the Kyngis grace,Methinks his gracious countenanceIn ryches is my sufficence."Not always so patient, however, he jogs James's memory with a hundred remedies. "God gif ye war Johne Thomsounis man!" he cries with rueful glee through a lively set of verses—

"For war it so than weill were meBot (without) benefice I wald not be;My hard fortune war endit thenGod gif ye war Johne Thomsounis man!"John Thomson's man was, according to the popular saying, a man who did as his wife told him; and Dunbar was strong in the Queen's favour. Therefore happy had been his fate had James been of this character. We cannot, however, follow the poet through all his pleadings and witty appeals and remonstrances, until at last in despairing jest he commends "the gray horse Auld Dunbar" to his Majesty, and draws or seems to draw at last a consolatory reply, which is thus recorded at the end of the poem under the title of "Responsio Regis."

"Efter our writtingis, TreasurerTak in this gray horse, Auld Dunbar,Which in my aucht with service trewIn lyart changit is his heu.Gar house him now against this YuillAnd busk him like ane Bischoppis muill,For with my hand I have indorstTo pay whatever his trappouris cost."Whether this response was really from James's hand or was but another wile of the eager suitor it is impossible to tell: but he did eventually have a pension granted him of twenty pounds Scots a year, until such time as a benefice of at least fifty pounds should fall to him; so that he was kept in hope. After this Dunbar tunes forth a song of welcome to "his ain Lord Thesaurair," in which terror at this functionary's inopportune absence—since quarterday we may suppose—is lost in gratulations over his return. "Welcome," he cries—

"Welcome my benefice and my rentAnd all the lyflett to me lent,Welcome my pension most preclair,Welcome my awin Lord Thesaurair."Thus the reckless and jolly priest carols. A little while after he has received his money he sings "to the Lordes of the King's Chacker," or Exchequer—

"I cannot tell you how it is spendit,But weel I wat that it is ended."These peculiarities, however, it need not be said do not belong entirely to the sixteenth century. The reader will find a great deal of beautiful poetry among the works of Dunbar. These lighter verses serve our purpose in showing once more how perennial has been this vein of humorous criticism, and frank fun and satire, in Scotland, in all ages, and in throwing also a broad and amusing gleam of light upon Edinburgh in the early fifteen hundreds, the gayest and most splendid moment perhaps of her long history.

All these splendours, however, were hard to keep up, and though Edinburgh and Scotland throve, the King's finances after a while seem to have begun to fail, and there was great talk of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land—it is supposed by the historians as a measure of securing that the King might not have the uncomfortable alternative of cutting short his splendours at home. This purpose, if it was gravely entertained at all, and not one of the proposals of change with which, when need comes, the impecunious of all classes and ages amuse themselves to put off actual retrenchment, never came to anything. And very soon there arose complications of various natures which threw all Christendom into an uproar. Henry VIII, young, arrogant, and hot-headed, succeeded his prudent father in England, and the treaty with the Scots which made, or seemed to make, England safe on the Borders, gave the English greater freedom in dealing with the other hereditary foe on the opposite side of the Channel; while France on her side began to use all possible efforts to draw from the English alliance the faithful Scots, who had always been the means of a possible diversion, always ready to carry fire and flame across the Border, and call back the warring English to look after their own affairs. James, with perhaps his head slightly turned by his own magnificence and the prosperity that had attended him since the beginning of his career, seemed to have imagined that he was important enough to play the part of peacemaker among the nations of Europe. And there are many embassies recorded of a bustling bishop, Andrew Forman, who seems for some time to have pervaded Christendom, now at Rome, now at Paris, now in London, with various confused negotiations. It was a learned age, and the King himself, as has been seen, had very respectable pretensions in this way; but that there was another side to the picture, and that notwithstanding the translator of Virgil, the three Universities now established in Scotland, and many men of science and knowledge both in the priesthood and out of it, there remained a strong body of ignorance and rudeness, even among the dignified clergy of the time, the following story, which Pitscottie tells with much humour of Bishop Forman, James's chosen diplomatist, will show.

"This bishop made ane banquet to the Pope and all his cardinals in one of the Pope's own palaces, and when they were all set according to their custom, that he who ought (owned) the house for the time should say the grace, and he was not ane good scholar, nor had not good Latin, but begane ruchlie in the Scottise fashione, saying Benedicite, believing that they should have said Dominus, but they answered Deus in the Italian fashioun, which put the bishop by his intendment (beyond his understanding), that he wist not well how to proceed fordward but happened in good Scottis in this manner, saying, what they understood not, 'The devil I give you all false cardinals to, in nomine Patris, Filii, et Spiritus Sancti, Amen.' Then all the bishop's men leuch, and all the cardinals themselves; and the Pope inquired whereat they leuch, and the bishop showed that he was not ane good clerk, and that the cardinals had put him by his text and intendment, therefore he gave them all to the devil in good Scottis, whereat the Pope himself leuch verrie earnestlie."

This did not prevent his Holiness, probably delighted with such a racy visitor, from making Forman Legate of Scotland; and it is to be feared that the meddling diplomatist with his want of education, was perhaps a better example of the clergy of Scotland, who about this time began to be the mark of all assailants as illiterate, greedy, vicious, and rapacious, than such a gentle soul as the other poet of the age, afterwards bishop of Dunkeld, the one mild and tranquil possessor of the great Douglas name.

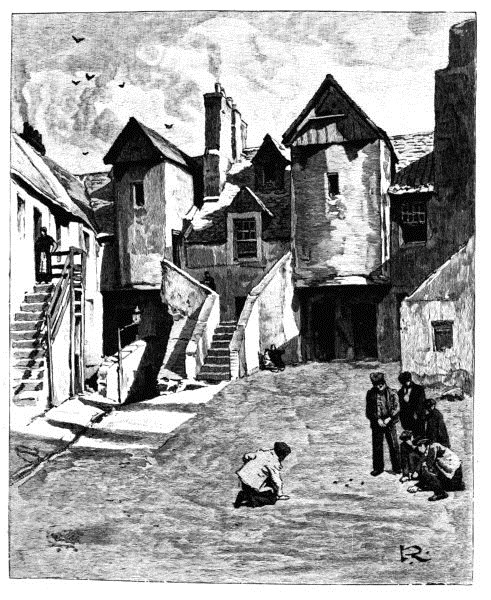

WHITE HORSE CLOSE

The imbroglio of events into which it is unnecessary for us to enter grew more and more complicated year by year, until at length it came to be a struggle between France and England for the ally who could be of most assistance to the one in the special way of injuring the other, and whom it was of the first advantage to both to secure. James was bound by the treaty of permanent peace which he had made at his marriage, and by that marriage itself, and no doubt the strong inclination of his wife, to England; but he was bound to France by a traditionary bond of a much stronger kind, by the memory of long friendship and alliance, and the persistent policy of his kingdom and race. The question was modified besides by other circumstances. England was, as she had but too often been, but never before in James's experience—harsh, overbearing, and unresponsive: while France, as was also her wont, was tender, flattering, and pertinacious. Henry refused or delayed to pay Queen Margaret a legacy of jewels and plate left to her by her father, and at the same time protected certain Borderers who had murdered a Scottish knight, and defended them against justice and James, while still summoning him to keep his word and treaty in respect to England; while on the other hand not only the King but the Queen of France appealed to James, he as to an ancient ally, she as to her sworn knight, to break that artificial alliance with his haughty brother-in-law. It may well have been that James in his own private soul had no more desire for such a tremendous step than the nobles who struggled to the last against it. But he had les défauts de ses qualités in a high degree. He was nothing if not a knight of romance. And though, as the poet has said—

"His own Queen Margaret, who in Lithgow's bowerAll silent sat, and wept the weary hour,"might be more to him than the politic Anne of France, or any fair lady in his route, it was not in him, a paladin of chivalry, the finest of fine gentlemen, the knight-errant of Christendom, to withstand a lady's appeal. Perhaps, besides, he was weary of his inaction, the only prince in Europe who was not inevitably involved in the fray; weary of holding tourneys and building ships (some of which had been lately taken by the English, turning the tables upon him) and keeping quiet, indulging in the inglorious arts of peace, while everybody else was taking the field. And Henry was arrogant and exasperating, so that even his own sister was at the end of her brief Tudor patience; and Louis was flattering, caressing, eloquent. When that last embassage of chivalry came with the ring from Anne's own finger, and the charge to ride three miles on English ground for her honour, it was the climax of many arguments. "He loves war," the Spaniard had said. "War is profitable to him and to the country"—a curious and pregnant saying. James would seem to have struggled at least a little against all the impulses which were pushing him forward to his doom. He promised a fleet to his lady in France for her aid—a fleet foolishly if not treacherously handled by Arran, and altogether diverted from its intended end; finally, that having failed, James flung away all precaution and yielded to the tide of many influences which was carrying him away.