Полная версия

Полная версияRoyal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

Notwithstanding, however, this little failure of respect to the sovereign, and the dismal uncertainty and anxiety in which his reign began, there seemed to be nothing but the happiest prospects opening before the young King. Out of the miserable struggle which brought him to the throne, he himself, most probably only awakened to the meaning of it after all was over, brought a lifelong remorse which he never threw off, and which was increased by the melancholy services of commemoration and expiation, the masses for his father's soul and solemn funeral ceremonials whether real or nominal, at all of which the youth would have to be present with a sore and swelling heart. We are told that he went and unburthened himself to the Dean of the Chapel Royal in Stirling, his father's favourite church, which James III had built and endowed, arranging the services and music with special personal care. The Dean received his confession with kindness seeing him so penitent, and gave him "good counsel and comfort," and remained his friend and spiritual adviser as he grew into manhood; but we are not told whether it was by his ordinance as a penance and constant reminder of his sin, or by a voluntary mortification of his own, that James assumed the iron belt which he wore always round him "and eikit it from time to time," that is, increased its size and weight as long as he lived. This sensibility, which formed part of his chivalrous and generous character, the noble, sweet, and lovable nature which conquered all hearts, at once subdued and silenced his many critics, and furnished them with a reproach which spite and ill-will could bring up against him when occasion occurred. But the enemies were few and the lovers many who surrounded the young Prince when the contentions of the crisis were once over, and the warring factions conciliated by general condemnations in principle which hurt nobody so long as they were not accompanied by confiscations or deprivations. Such clemency in so young a king was a marvel to all, the chroniclers say, though indeed there could be little question of clemency on James's part in a mutual hushing-up, which was evidently dictated by every circumstance of the time and the only source of mutual safety.

When, however, he had arrived at man's estate, and makes a recognisable and individual appearance upon the stage of history, the picture of him is one of the most attractive ever made, the happiest and brightest chapter in the tragic story of the Stewarts. Youth with that touch of extravagance which becomes it, that genial wildness which all are so ready to pardon, and an adventurous disposition, careless of personal safety, gave a charm the more to the magnificent young King, handsome, noble, brave, and full of universal friendliness and sympathy, who comes forth smiling in the face of fate, ready to turn back every gloomy augury and bring in another golden age. Pitscottie's description is full of warmth and vivid reality:—

"In this mean time was good peace and rest in Scotland and great love betwixt the King and all his subjects, and was well loved by them all: for he was verrie noble, and though the vice of covetousness rang over meikle in his father it rang not in himself: nor yet pykthankis nor cowards should be authorised in his companie, nor yet advanced; neither used he the council but of his lords, whereby he won the hearts of the whole nobilitie; so that he could ride out through any part of the realme, him alone, unknowing that he was King; and would lie in poor men's houses as he had been ane travellour through the country, and would require of them where he lodged, where the King was, and what ane man he was, and how he used himself towards his subjects, and what they spoke of him through the countrie. And they would answer him as they thought good, so by this doing the King heard the common bruit of himself. This Prince was wondrous hardie and diligent in execution of justice, and loved nothing so well as able men and horses; therefore at sundry times he would cause make proclamations through the land to all and sundry his lords and barons who were able for justing and tourney to come to Edinburgh to him, and there to exercise themselves for his pleasure, some to run with the spear, some to fight with the battle-axe, some with the two-handed sword, and some with the bow, and other exercises. By this means the King brought the realm to great manhood and honour: that the fame of his justing and tourney spread through all Europe, which caused many errant knights to come out of other parts to Scotland to seek justing, because they heard of the kinglie fame of the Prince of Scotland. But few or none of them passed away unmatched, and ofttimes overthrown."

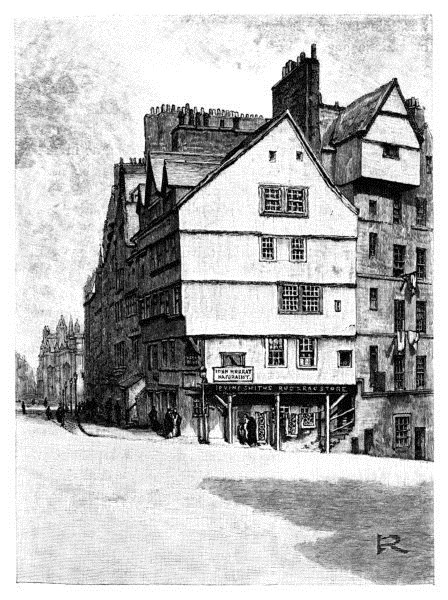

The town to which, under this young and gallant Prince, the stream of chivalry flowed, was yet more picturesque than the still and always "romantic town" of which every Scotsman is proud. The Nor' Loch reflected the steep rocks of the castle and the high crown of walls and turrets that surmounted them, with nothing but fields and greenery, here and there diversified by a village and fortified mansion between it and the sea. The walls, which followed the irregularities of the rocky ridge, as far as the beginning of the Canongate, were closed across the High Street by the picturesque port and gateway of the Nether Bow, the boundary in that direction of the town, shutting in all its busy life, its markets, its crowding citizens, its shops and churches. On the south at the foot of the hill, the burghers' suburb, where the merchants, lawyers, and even some of the nobles had their houses and gardens, lay outside the walls in the sunshine, protected only by the soft summits of the Braid and Pentland hills: what is now the Cowgate, not a savoury quarter, being then the South Side, the flowery and sheltered faubourg in which all who could afford the freedom of a country residence while still close to the town, expanded into larger life, as the wealthy tradesfolk of all ages, and persons bound to a centre of occupation and duty, always love to do. Towards the east, and gradually becoming as important and busy as the High Street itself, though outside the series of towers which guarded the city gate, lay the long line of the Court suburb, the lofty and noble Canongate descending towards the abbey and palace, where all that was splendid in Scotland congregated around the gay and gallant King. Outside the Netherbow Port, striking out in opposite directions, was the road which led to the seaport of Leith and that which took its name from the great Kirk of Field, St. Mary's Wynd, a pleasant walk along the outside of the fortifications to the great monastery on its plateau, with the Pleasance, a name suggestive of all freshness and greenery and rural pleasure, at its feet. Inside the town, between the castle gates and those of the city, were the crowded habitations of a mediæval town, the only place where business could be carried on in safety, or rich wares exhibited, or money passed from hand to hand. The Lawnmarket or Linen Market would be the chief centre of sale and merchandise, and there, no doubt, the booths before the lower stories, with all their merchandise displayed, and the salesmen seated at the head of the few deep steps which led into the cavernous depths within, would be full of fine dresses and jewellery, and the gold and silver which, some one complains, was worn away by the fine workmanship, which was then more prized than solid weight. The cloth of gold and silver, the fine satins and velvets, the embroidery, more exquisite than anything we have time or patience for now—embroidery of gold thread which we hear of, an uncomfortable sort of luxury, even upon the linen of great personages—would there be put forth and inspected by gallants in all their fine array, or by the ladies in their veils, half or wholly muffled from public inspection. Even the cheaper booths that adorned the West Bow or smaller wynds, where the country women bought their kirtles of red or green when they brought their produce to the market, would show more gay colours under their shade in a season than we with our soberer taste in years; and the town ladies, in their hoods and silk gowns, which were permitted even in more primitive times to the possessors of so much a year, must have been of themselves a fair sight in all their ornaments, less veiled and muffled from profane view than more high-born dames and demoiselles. No doubt it would be a favourite walk with all to pass the port and see what was doing among the great people down yonder at Holyrood, or watch a gay band of French knights arriving from Leith with their pennons displayed, full of some challenge lately given by the knights of Scotland, or eager to maintain on their own account the beauty of their ladies and the strength of their spears against all comers. Edinburgh can never have been so amusing, never so gay and bright, as in these fine times; though, no doubt, there was always the risk of a rush together of two parties of gallants, a mêlée after the old mode of Clear the Causeway, a hurried shutting of shops and pulling forth of halberds. For the younger population, at least, no doubt these risks were almost the best part of the play.

OLD HOUSES AT HEAD OF WEST BOW

Thus Edinburgh breasted its ridge of rock—a fair sight across all the green country; its sentinel mountain crouching eastward between the metropolis and the sea, its suburbs growing and expanding; this full of the fine people of the Court, that of the quiet wealth and enjoyment which made no extravagant demonstration. It had never been so prosperous, never so much the centre of all that was splendid in the kingdom, as in the reign of the fourth James—the knight of romance, the gayest and brightest representative of the House of Stewart, though unable to defend himself from the tragic fate which awaited every sovereign of his name.

Among the finest sights seen in Edinburgh must have been those which occurred very early in his reign, when the great Admiral, Sir Andrew Wood, he who had met so proudly the inquisition of the lords, came from sea with his prisoners and his spoils. Wood had not pleased the reigning party by his rough fidelity to the dead King, but they could not induce the other sea captains, by any promise of reward or advancement, to attack and punish, as was their desire, the greatest sailor in Scotland. And when an English expedition began to vex the Scottish coasts, there was no one but Wood to encounter and defeat them, which he did on two different occasions, bringing the captains of the rover vessels—probably only half authorised by the astute King Henry VII, who had evidently no desire to attack Scotland, but who had to permit a raid from time to time as the most popular thing to do—as prisoners to the courteous King, who though he "thanked Sir Andrew Wood greatly and rewarded him richlie for his labours and great proof of his manhood," yet "propined (gave presents to) the English captain richlie and all his men and sent them all safelie home, their ships and all their furnishing, because they had shown themselves so stout and hardie warriours." "So he sent them all back to the King of England," says the chronicler, with full enjoyment of James's magnanimous brag and of thus having the better of "the auld enemy" both in prowess and in courtesy, "to let him understand he had as manlie men in Scotland as he had in England; therefore desired him to send no more of his captains in time coming." England was obliged to accept, it appeared, this bravado of the Scots, having no excuse for repeating the experiment, but was "discontented" and little pleased to be overcome both in courtesy and in arms.

A more serious matter than this encounter at sea, which was really more a trial of strength than anything else, was the purely chivalric enterprise of James in taking up the cause of Perkin Warbeck, the supposed Duke of York, who imposed upon all Europe for a time, and on nobody so much as the King of Scotland. This adventurer, who was given out as the younger son of Edward IV escaped by the relenting of the murderers when his elder brother was killed in the Tower, was by unanimous consent of all history a youth of person and manners quite equal to his pretensions, playing his part of royal prince with a grace and sincerity which nobody could resist. The grave Pinkerton, so sarcastically superior to all fables, writing at the end of the eighteenth century, had evidently not even then made up his mind how to accept this remarkable personage, but speaks of him as "this unfortunate prince or pretender," and of James as "sensible of the truth of his report or misled by appearance," with an evident leaning to the side of the hero who played so bold a game. The young adventurer came to James with the most illustrious of guarantees. He brought letters from Charles VIII of France, and from the Emperor Maximilian, and was followed by a train of gallant Frenchmen and by everything that was princelike, gracious, and splendid. So completely was he received and believed at the Scottish Court that when there arose a mutual love, as the story goes, between him and the Lady Catherine Gordon, daughter of the Earl of Huntly, one of the most powerful peers in Scotland, and at the same time of royal blood, a cousin of the King, the marriage seems to have been accepted as a most fit and even splendid alliance. No greater pledge of belief could have been given than this. The King of Scots threw himself into the effort of establishing the supposed prince's claims as if they had been his own. Curious negotiations were entered into as to what the pretender should do if, by the help of Scotland, he was placed upon the English throne. He was to cede Berwick, that always-coveted morsel which had to change its allegiance from generation to generation as the balance between the nations rose and fell—and pay a certain sum towards defraying the expenses of the expedition, a bargain to which Perkin, playing his part much better than any king of the theatre ever did before, demurred, insisting upon easier terms—as he afterwards remonstrated when James harried the Borders, declaring that he would rather resign all hopes of the crown than secure it at the expense of the blood and goods of his people. A pretended prince who thus spoke might well be credited as far as faith could go. The story of this strange enterprise is chiefly told in the letters to Henry VII of England of Sir John Ramsay, the same who had been saved by James III when the rest of his favourites were killed, and who had more or less thriven since, though in evil ways, occupying a position at the Court of James IV whom he hated, and acting as spy on his actions, which were all reported to the English Court. Ramsay gives the English Government full information of all that his sovereign is about to do on behalf of the fengit (feigned) boy, and especially of the invasion of England which he is about to undertake "against the minds of near the whole number of his barons and people. Notwithstanding," Ramsay says, "this simple wilfulness cannot be removed out of the King's mind for nae persuasion or mean. I trust verrilie," adds the traitor, "that, God will, he be punished by your mean for the cruel consent of the murder of his father."

Curiously enough Pitscottie, the most graphic and circumstantial of historians, says nothing whatever of this most romantic episode. Why he should have left it out, for it is impossible that it could have been unknown to him, we are unable to imagine; but so it is. Buchanan however enters fully into the tale. The wisest of James's counsellors, he tells us, were disposed to have nothing to do with this spurious young prince coming out of the unknown with his claim to be the rightful King of England; but many more were in his favour, specially with the reflection that the moment of England's difficulties was always one of advantage for the Scots. An army was accordingly raised, with which James marched into England, carrying Perkin with him with a train of about fourteen hundred followers, and hopes that the country would rise to greet and acknowledge their lost prince. But it is evident that the Northumbrians looked on without any response, and saw in the expedition but one of the many raids which they were always so ready to return on their side when occasion offered. The pretender, on whose behalf all this was done, shrank, it would appear, from the devastation, and with something like the generous compunction of a prince protested that he would rather lose the crown than gain it so—a protest which James must have thought a piece of affectation, for he replied with a jeer that his companion was too solicitous for the welfare of a country which would neither acknowledge him as prince nor receive him as citizen. Perkin must have begun to tire the patience of the finest gentleman in Christendom before James would have made such a contemptuous retort. He returned with the King, however, when this unsuccessful expedition—the only use of which was that it proved to James the fruitlessness of fighting on behalf of a pretender who had no hold upon the people over whom he claimed to reign—came to an end. It was followed by some slight reprisals on the part of the English, and after an interval by an embassy to make peace. Henry VII would seem to have been at all times most unwilling to have Scotland for an enemy, notwithstanding the strange motive suggested to him by the traitor Ramsay. "Sir," writes this false Scot, "King Edward had never fully the perfect love of his people till he had war with Scotland; and he made sic good diligence and provision therein that to this hour he is lovit; and your Grace may as well have as gude a tyme as he had." But the cunning old potentate at Westminster was not moved even by this argument. Instead of following the instructions of the virulent spy whose hatred of his native king and country reaches the height of passion, he sent a wise emissary, moderate like himself, the Bishop of Durham, to inquire into the reasons of the attack.

And Edinburgh must have had another great sensational spectacle in the arrival not only of the English commissioners, but of such a great foreign personage as the Spanish envoy, one of the greatest grandees of the most splendid of continental kingdoms, who had come to England to negotiate the marriage of Catherine of Arragon with the Prince of Wales, and who continued his journey to Scotland with letters of amity from his sovereigns for James, and with the object of assisting in the peacemaking between the two Kings. Henry required James to give up the pretender into his hands—a thing which of course it was not consistent with honour to do—but it was evident that the King of Scots had already in his own mind given up the adventurer's cause. And after the negotiations had been concluded and peace made between England and Scotland, Perkin and his beautiful young wife and his train of followers set sail from Scotland in a little flotilla of three ships, intending it is said to go to Ireland, where he had been well received before coming to the Court of James. The imagination follows with irrestrainable pity the forlorn voyage of this youthful band of adventurers: the young husband trained to all the manners and ways of thinking of a prince, however little reality there might be in his claims; the young wife, mild and fair, the White Rose as she was called, with the best blood of Scotland in her veins; the few noble followers, knights, and a lady or two who shared their fortunes, setting out vaguely to sea, not knowing were to go, with the world before them where to choose. When they got to Ireland Prince Perkin heard of an insurrection in Cornwall, and hastened to put himself at the head of it, placing his wife for security in the quaint fortress, among the waters, of St. Michael's Mount. But the insurrection came to nothing, and "the unfortunate prince or adventurer" was taken prisoner. He was pardoned it is said, but making a wild attempt at insurrection again, was this time tried and executed. His White Rose, most forlorn of ladies, was taken by King Henry from her refuge at the end of the world, placed in charge of the Queen, and never left the English Court again. There is no record that she and her husband were ever allowed to meet. So ends one of the saddest and most romantic of historical episodes.

This story takes up a large part of the early reign of James, who no doubt saw his error at the last, but in the beginning threw himself into Perkin's fortunes with characteristic impetuosity, and thought nothing too good, not even his own fair kinswoman, for the rescued prince. It was an error, however, that James shared with many high and mighty potentates who gave their imprimatur at first to the adventurer's cause. But even for the most genuine prince, when only a pretender, the greatest sovereigns are but poor supporters in the long run. James had a hundred things to do to make him forget that unfortunate adventure of Perkin. It was in the year 1497 that this incident ended so far as the Scottish Court was concerned, and James returned to the natural course of his affairs, not without occasional tumults on the Border, but with no serious fighting anywhere for a course of pleasant years. The old traditional strife between the King and the nobles no longer tore the kingdom asunder. Perhaps the first great event of his life, the waking up of his boyish conscience to find himself in the camp of a faction pitted against his own father, influenced him throughout everything, and made the duty of conciliation and union seem the first and most necessary; perhaps it was but the natural revulsion from those methods which his father had adopted to his hurt and downfall; or perhaps James's chivalrous temper, his love of magnificence and gaiety, made him feel doubly the advantage of courtiers who should be great nobles and his peers, not dependants made splendid by his bounty. At all events the King lived as no Stewart had yet lived, surrounded by all without exception who were most noble in the land, encouraging them to vie with him in splendour, in noble exercises and pastimes, and almost, it may be imagined—with a change of method, working by good example and genial comradeship what his predecessors had vainly tried to do by fire and sword—tempting them to emulate him also in preserving internal peace and a certain reign of justice throughout the country. There was no lack of barons in the Court of James. Angus and Home and Huntly, who had pursued his father to the death and placed himself upon the throne, were not turned into subservient courtiers by his gallantry and charm: but neither was there any one of these proud lords in the ascendant, or any withdrawn and sullen in his castle, taking no share in what was going on. The machinery of the State worked as it had never done before. There were few Parliaments, and not very much law-making. Enough laws had been made under his predecessors, "if they had but been kept," to form an ideal nation; the thing to do now was to charm, to persuade, to lead both populace and nobility into respecting them. It would be vain to imagine that this high purpose was always in James's mind, or that his splendour and gaieties were part of a plan for the better regulation of the kingdom. But that he was not without a wise policy in following his own character and impulses, and that the spontaneous good-fellowship and sympathy which his frank, genial, and easy nature called forth everywhere were not of admirable effect in the welding together of the nation, it would be unjust to say. If he had not the sterner nobility of purpose which made the first of his name conceive and partially carry into effect the ideal reign of justice which was the first want of his kingdom, he had yet a noble ambition for Scotland to make her honoured and feared and famous, and the success with which he seems to have carried out this object of his life for many years was great. He made the little northern kingdom known for a centre of chivalry, courtesy, courage, and, what was more wonderful, magnificence, as it had never been before. He penetrated that country with traditions and associations of himself in the character always attractive to the imagination, of that prince of good fellows, the wandering stranger, who came in unknown and sought the hospitality of farmer or ploughman, and made the humble board ring with wit and jest, and who thereafter was discovered by sudden gift, or grace, or unexpected justice, to be the King:—

"He took a bugle from his side, and blew both loud and shrill,And four and twenty belted knights came trooping owre the hill;""Then he took out his little knife, let a' his duddies fa',And he was the brawest gentleman that was among them a'."The goodman of Ballangeich,3 the jovial and delightful Gaberlunzie, the hero of many a homely ballad and adventure, some perhaps a trifle over free, yet none involving any tragic treachery or betrayal, James was the playfellow of his people, the Haroun al Raschid of Scotch history. "By this doing the King heard the common brute (bruit) of himself." Thus he won not only the confidence of the nobles but the genial sympathy and kindness of the poor. A minstrel, a poet too in his way a man curious about all handicrafts, famous in all exercises, "ane singular good chirurgian, so that there was none of that profession if they had any dangerous case in hand but would have craved his advice "—he had every gift that was most likely to commend him to the people, who were proud of a king so unlike other kings, the friend of all. And nothing could exceed the activity of the young monarch, always occupied for the glory of Scotland whatever he was doing. It was he who built the great ship, the Michael, which was the greatest wonder ever seen in the northern seas; a ship which took all the timber in Fife to build her (the windswept Kingdom of Fife has never recovered that deprivation) besides a great deal from Norway, with three hundred mariners to work her, and carrying "ane thousand men of warre" within those solid sides, which, all wooden as they were, could resist cannon shot. "This ship lay in the road, and the King took great pleasure every day to come down and see her," and would dine and sup in her, and show his lords all her order and provisions; No doubt there were many curious parties from Edinburgh who followed the King to see that new wonder, and that groups would gather on the ramparts of the castle to point out on the shining Firth the great and lofty vessel, rising like another castle out of the depths. James had also the other splendid taste, which his unfortunate father had shared, of building, and set in order the castle at Falkland in the heart of the green and wealthy Fife—where there was great hunting and coursing, and perhaps as yet not much high farming in those days—and continued the adornments of Stirling, already so richly if rudely decorated in the previous reign.